Ottoman reconquest of the Morea

The Ottoman reconquest of the Morea took place in June–September 1715, during the Seventh Ottoman–Venetian War. The Ottoman army, under Grand Vizier Silahdar Damat Ali Pasha, aided by the fleet under Kapudan Pasha ('Grand Admiral') Canım Hoca Mehmed Pasha, conquered the Morea (more commonly known as the Peloponnese) peninsula in southern Greece, which had been captured by the Republic of Venice in the 1680s, during the Sixth Ottoman–Venetian War. The Ottoman reconquest inaugurated the second period of Ottoman rule in the Morea, which ended with the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in 1821.

Background

Following the Ottoman Empire's defeat in the Second Siege of Vienna in 1683, the Holy League of Linz gathered most European states (except for France, England and the Netherlands) in a common front against the Ottomans. In the resulting Great Turkish War (1684–1699) the Ottoman Empire suffered a number of defeats such as the battles of Mohács and Zenta, and in the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699), was forced to cede the bulk of Hungary to the Habsburg monarchy and Podolia to Poland-Lithuania, while Azov was taken by the Tsardom of Russia.[1] Further south, the Republic of Venice had launched its own attack on the Ottoman Empire, seeking revenge for successive conquests of its overseas empire by the Turks, most recently (1669) the loss of Crete. During the conflict, Venetian troops seized the island of Cephalonia (Santa Maura) and the Morea peninsula, although they failed to retake Crete and expand their possessions in the Aegean Sea.[2]

The Ottomans were from the outset determined to reverse their territorial losses, especially the Morea, whose loss had been particularly keenly felt in the Ottoman court: a large part of the income of the Valide Sultan (the Ottoman queen-mother) had come from there. Already in 1702, there were tensions between the two powers and rumours of war because of the Venetian confiscation of an Ottoman merchant vessel. Troops and supplies were moved to the Ottoman provinces adjoining the Venetian "Kingdom of the Morea". The Venetian position there was weak, with only a few thousand troops in the whole peninsula, plagued by supply, disciplinary and morale problems. Nevertheless, peace was maintained between the two powers for twelve more years.[3] In the meantime, the Ottomans began a reform of their navy, while Venice found itself increasingly isolated diplomatically from the other European powers: the Holy League had fractured after its victory, and the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) and the Great Northern War (1700–1721) preoccupied the attention of most European states.[4] The Ottomans took advantage of the favourable international situation and secured their northern flank by defeating Russia in 1710–1711. After the end of the Russo-Turkish war, the emboldened Ottoman leadership, under the new Grand Vizier, Silahdar Damat Ali Pasha, turned its attention to reversing the losses of Karlowitz. Profiting from the general war weariness that made any intervention by the other European powers unlikely, the Porte turned its focus on Venice.[5][6][7]

Preparations and opposing forces

Venice

The inability of the Venetians to effectively defend the Morea had been apparent already during the latter stages of the Great Turkish War, when the Greek renegade Limberakis Gerakaris had launched dangerous raids into the peninsula.[8] The Republic was well aware of the Ottoman ambitions to recover the Morea, both for reasons of prestige and because of the potential threat to the Ottoman possessions in the rest of Greece posed by Venetian possession of the peninsula: with the Morea as a springboard, the Venetians might seek to reclaim Crete, or foment anti-Ottoman rebellions in the Balkans.[9]

Consequently, from the beginning of its rule, Venice's officials toured the fortresses to ascertain their state and their capacity to resist. However, the Venetians' position was hampered by problems of supplies and morale, as well as the extreme lack of troops available: in 1702, the garrison at the Acrocorinth, which covered the Isthmus of Corinth, the main invasion route from the mainland, numbered only 2,045 infantry and barely a thousand cavalry.[10] The peacetime Venetian military system, which consisted of a small permanent army and spread it among small garrisons (presidi) in the colonies, also proved a problem, as it prohibited a rapid mobilization and concentration of a large force. Furthermore, such a force was essentially an infantry army, short in cavalry and hence forced to avoid pitched battles and concentrate on sieges.[11] The Venetian militia (cernide) system was problematic as well, being plagued by money shortages and the reluctance of the colonial subjects to serve in it. For example, out of 20,120 men deemed fit for duty in 1690, only 662 actually joined the militia in the Morea.[12] The Venetian army in the Morea particularly lacked cavalry. Only three dragoon regiments of five companies each, and the Croat cavalry regiment of Antonio Medin, with eight companies, were stationed in the Morea. The quality of both the men and their horses was judged as extremely poor, and peacetime losses through desertion or disease meant that they were never at full strength.[13][14]

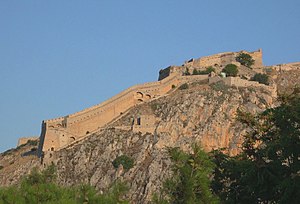

In light of these facts, the Venetian governors in the Morea quickly concentrated their attention to the fortifications. However, although a detailed survey in 1698 found serious deficiencies in all the fortresses of the Morea, little seems to have been done to address them.[15] In 1711, Daniele Dolfin, charged with inspecting the situation in the peninsula, warned that unless the many deficiencies were addressed soon, it would be lost in a coming war. He also recommended that, given the lack of funds and men, and the inability of either the available army or the navy to stop an Ottoman invasion over land, the defence of the Morea should be limited to a handful of strategically important fortresses: the capital Nauplia, the Acrocorinth, the Castle of the Morea at the entrance of the Corinthian Gulf, and the coastal castles of Modon and Monemvasia. It was hoped that by concentrating the available resources in strengthening these, they could be made impregnable.[16] Almost the only major new fortification undertaken by the Venetians during their rule in the Morea was the new citadel for Nauplia, built in 1711–1714 on the height of Palamidi overlooking the city and the approaches to it.[15][17][18]

The forces available to the Republic in the Morea on the eve of the war were fewer than 5,000 men, and dispersed among the various fortresses.[19] According to a contemporary register preserved in Montreal, the total strength of Venetian regular troops in the Morea was 4,414 men:[20][a]

- Nauplia: 1,716 men (370 for Palamidi), under the provveditore generale Alessandro Bon

- Acrocorinth (Corinth): 330 men, plus 162 Albanians for covering the Isthmus, under the provveditore straordinario Giacomo Minotto

- Castle of the Morea (Rio): 786 men, under the provveditore straordinario Marco Barbarigo

- Monemvasia: 261 men, under the provveditore straordinario Federgo Badoer

- Kelefa: 45 men, under the provveditore Paulo Donà

- Zarnata: 83 men, under the provveditore Bembo

- Coron: 282 men, under the provveditore Agostin Balbi

- Modon: 691 men, under the provveditore straordinario Vincenzo Pasta

- Aigina: 58 men, under the provveditore Francesco Bembo

Apostolos Vakalopoulos gives similar, but slightly different numbers: 1747 (397 cavalry) at Nauplia, 450 at Corinth, 466 infantry and 491 at Rio and its region, 279 at Monemvasia, 43 each at Kelefa and Zarnata, 719 (245 cavalry) at Coron and Modon, and 179 infantry and 125 at Navarino, for a total of 4,527 men.[22] The strength of the cernide militias is unknown.[13]

These forces were clearly inadequate to confront an Ottoman army of 200,000 men, as the various reports received by the Venetian commanders claimed.[23] The Venetian government also delayed ins ending reinforcements to the Morea: the first convoy, under Lodovico Flangini, arrived in the peninsula in late March, but comprised only two ships carrying ammunition.[24] As a result, in March 1715 the Venetians decided to concentrate their defence on Nauplia, the Acrocorinth, the Castle of the Morea, and Monemvasia. The Venetian commanders hoped to be able to hold Navarino and Coron as well, but already in April, Dolfin judged that these would have to be abandoned as well.[25]

On the outbreak of the war, the Venetians called for aid from the other European states, but due to the Republic's diplomatic isolation and the preoccupation of the European powers with other conflicts, response was slow: apart from the Pope and the Crusading orders of the Knights Hospitaller and the Knights of St. Stephen, who immediately dispatched a few warships, the major European powers offered help only after the loss of the Morea.[26][27] Even after the arrival of these auxiliary squadrons, in July 1715 Dolfin only possessed 22 ships of the line, 33 galleys, 2 galleasses and 10 galliots, and was at a considerable disadvantage against the Ottoman fleet, which forced him to maintain a rather passive stance.[28][29]

Venetian appeals to the local Greek inhabitants were also ineffective, especially in continental Greece: most of the Greeks remained either neutral or actively joined the Ottomans.[30] The Ottomans actively encouraged this with proclamations that life, property, and privileges of ecclesiastical and administrative autonomy would be respected.[30] News that the Patriarch of Constantinople had excommunicated anyone helping the Venetians in whatever manner also influenced the Greek attitudes.[31] This was a severe blow to the Venetians: many leaders of armed bands joined the Ottoman army, bolstering the latter instead of the numerically much inferior Venetian forces, while the Ottomans were able to dominate the countryside, where the Greek peasantry readily provided food and supplies to the Ottoman forces.[30] Even where some Greek leaders, notably in the Mani Peninsula, decided to assist the Venetians, they made this conditional on the Venetian providing arms and supplies. In the event, the rapid Ottoman advance and the absence of an effective Venetian response persuaded them to remain neutral.[30]

Ottomans

The Ottoman army in 1714 was still organized in the "classical" manner of the previous centuries, with a core of elite kapikulu troops, notably the Janissaries that formed the core of any expeditionary army, augmented by provincial levies and timariot cavalry.[32] Ottoman armies were distinguished by the presence of large numbers of cavalry, which formed about 40% of a field army, but its effectiveness against European regular infantry had diminished much in the previous decades, as shown in the Great Turkish War.[33] Still, it retained its tactical mobility, whereas the Ottoman infantry was a far more static force, capable either of last-stand defence or mass attack, but not much else.[34] The indiscipline of the Janissaries also proved a constant headache for the Ottoman commanders.[34]

During the early months of 1715, the Ottomans assembled their army in Macedonia under the Grand Vizier Silahdar Damat Ali Pasha. On 22 May, Grand Vizier marched south from Thessalonica, arriving at Thebes on 9 June, where he held a review of the troops.[35] Although the accuracy of his figures is open to doubt, Brue reports 14,994 cavalry and 59,200 infantry as present at Thebes on 9 June, with the total number of men involved in the campaign against the Morea placed at 110,364 (22,844 cavalry and 87,520 infantry).[36] The cavalry numbers given by Brue are about half those expected for an Ottoman force of this size, indicating that likely the Ottoman commanders had to begin the campaign before their entire army was assembled.[37] The army's artillery park comprised 111 light field guns, 15 larger siege guns, and 20 mortars.[37]

The army was aided by the Ottoman fleet, which operated in close coordination with it. Like the Venetians, the Ottoman navy was a mixed force of sailing ships of the line and rowed galleys.[38] The Ottomans also secured the assistance of their North African vassals, the regencies of Tripoli, Tunis, and Algiers, and their fleets.[8][39] Commanded by the capable Kapudan Pasha Canım Hoca Mehmed Pasha, the fleet that sailed from the Dardanelles in June 1715 numbered 58 ships of the line, 30 galleys, five fireships, and 60 galliots, along with cargo vessels.[8][27][39]

The Ottoman view on the campaign is known mostly through two eyewitness accounts, the diary of the French embassy interpreter Benjamin Brue (published as Journal de la campagne que le Grand Vesir Ali Pacha a faite en 1715 pour la conquête de la Morée, Paris 1870), and that of Constantine the "Dioiketes", a guard officer to the Prince of Wallachia (published by Nicolae Iorga in Chronique de l’expédition des Turcs en Morée 1715 attribuée à Constantin Dioikétès, Bucarest 1913).

Attack on the Morea

After a war council on 13 June, 15,000 Janissaries under Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Pasha—governor of Diyarbekir Eyalet and nephew of the namesake Grand Vizier who led the Siege of Vienna in 1683[40]— were sent to capture Lepanto, and thence cross into the northwestern Morea to attack the Castle of the Morea and Patras, while the main body of the army under Yusuf Pasha and the Agha of the Janissaries moved onto the Isthmus of Corinth, and thence to the Argolid and southwest, across the central Morea, to Messenia, assisted by supplies from the fleet.[19][35] At the same time, the Ottoman fleet had captured the last Venetian possessions in the central Aegean, the islands of Tinos (5 June) and Aigina (7 July), and proceeded to blockade the Venetian positions in the Morea. The Ottomans operated with impunity as the Venetian fleet remained in the Venetian Ionian Islands.[41]

"Sent by the state to guard the land,

(Which, wrested from the Moslem's hand,

While Sobieski tamed his pride

By Buda's wall and Danube's side,

The chiefs of Venice wrung away

From Patra to Euboea's bay,)

Minotti held in Corinth's towers

The Doge's delegated powers,

While yet the pitying eye of Peace

Smiled o'er her long forgotten Greece:"

Excerpt from Lord Byron's The Siege of Corinth (1816).[42]

According to a report by Minotto, the Ottoman advance guard entered the Morea on 13 June.[42] The first Venetian fortress was the citadel of Acrocorinth, held by little over 300 Venetian and about 110 Greek and Albanian auxiliaries. The Venetian garrison was weakened by maladies, and the artillery was badly maintained and with insufficient ammunition. By 2 July, the Ottomans had breached the walls in two places. As the fortress was about to fall, the large number of civilian refugees began pressuring Minotto to capitulate. Terms were arranged for the safe passage for the garrison to Corfu, and the garrison began leaving the citadel on 5 July. However, some Janissaries, eager for plunder, disobeyed Damat Ali's orders and entered the citadel. A large part of the garrison and most of the civilians were massacred or sold to slavery (including Minoto). Only 180 Venetians were saved and transported to Corfu.[43][19][44] These tragic events later inspired Lord Byron's poem The Siege of Corinth.[42]

After Corinth, the Ottomans passed by Argos on 9 July, which they found abandoned, and arrived before Nauplia three days later.[19] Nauplia, the main stronghold of Venetian power in the Morea, was the best-fortified overseas possession of the Republic. With ample stores, a garrison of about 3,000 men, and an artillery complement of at least 150 guns, the city was expected to hold for at least three months, allowing for the arrival of reinforcements over the sea.[19][45] On 20 July, after only nine days of siege, the Ottomans exploded a mine under the bastions of Palamidi and successfully stormed the fort. The Venetian defenders panicked and retreated, leading to a general collapse of the defence.[46]

The Ottomans then advanced to the southwest, where the forts of Navarino and Koroni were abandoned by the Venetians, who gathered their remaining forces at Methoni (Modon). However, being denied effective support from the sea by Delfin's reluctance to endanger his fleet by engaging the Ottoman navy, the fort capitulated.[47] The remaining Venetian strongholds, including the last remaining outposts on Crete (Spinalonga and Souda), likewise capitulated in exchange for safe departure. Within a hundred days, the entire Peloponnese had been re-taken by the Ottomans.

According to the Ottomanist Virginia Aksan, the campaign had been "basically a walkover for the Ottomans". Despite the presence of sufficient material, the Venetian garrisons were weak, and the Venetian government unable to finance the war, while the Ottomans not only enjoyed a considerable numerical superiority, but also were more willing "to tolerate large losses and considerable desertion": according to Brue, no less than 8,000 Ottoman soldiers were killed and another 6,000 wounded in the just nine days of the siege of Nauplia.[48] Furthermore, unlike the Venetians, the Ottomans this time enjoyed the effective support of their fleet, which among other activities ferried a number of large siege cannons to support the siege of Nauplia.[49]

On 13 September, the Grand Vizier began his return journey, and on the 22nd, near Nauplia, received the congratulations of the Sultan. A week of parades and celebrations followed. On 10 October, the Standard of the Prophet was ceremonially placed in its casket, a sign that the campaign was over. The troops received six months' worth of pay on 17 October near Larissa, and the Grand Vizier returned to the capital, for a triumphal entrance, on 2 December.[35]

Notes

- ^ Older scholars, such as George Finlay and William Miller, state slightly larger numbers, around 8,000 or even 10,000 men. These were the total land forces available to the overseas command under the Captain General of the Sea Daniele Dolfin, from Dalmatia to the Aegean.[21]

References

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 14–19.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 19–35.

- ^ Setton 1991, pp. 412–418.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 38, 41.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Setton 1991, pp. 421–426.

- ^ Hatzopoulos 2002, pp. 38–44.

- ^ a b c Chasiotis 1975, p. 41.

- ^ Hatzopoulos 2002, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Setton 1991, p. 418.

- ^ Prelli & Mugnai 2016, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Hatzopoulos 2002, p. 31.

- ^ a b Hatzopoulos 2002, p. 35.

- ^ Pinzelli 2003, pp. 363, 436–438, 479.

- ^ a b Setton 1991, p. 399.

- ^ Hatzopoulos 2002, pp. 32–33, 42.

- ^ Hatzopoulos 2002, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Pinzelli 2003, pp. 429–432.

- ^ a b c d e Chasiotis 1975, p. 42.

- ^ Pinzelli 2003, pp. 479–481.

- ^ Pinzelli 2003, p. 479 (note 6).

- ^ Vakalopoulos 1973, p. 77.

- ^ Pinzelli 2003, pp. 479, 481.

- ^ Pinzelli 2003, p. 479.

- ^ Pinzelli 2003, p. 481.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 39, 41.

- ^ a b Anderson 1952, p. 244.

- ^ Anderson 1952, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Nani Mocenigo 1935, p. 318.

- ^ a b c d Chasiotis 1975, p. 39.

- ^ Nani Mocenigo 1935, p. 319.

- ^ Prelli & Mugnai 2016, pp. 27–38.

- ^ Prelli & Mugnai 2016, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b Prelli & Mugnai 2016, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Aksan 2013, p. 99.

- ^ Aksan 2013, pp. 99, 124 (note 55).

- ^ a b Prelli & Mugnai 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Prelli & Mugnai 2016, pp. 39–41.

- ^ a b Prelli & Mugnai 2016, p. 41.

- ^ Prelli & Mugnai 2016, p. 45.

- ^ Chasiotis 1975, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b c Pinzelli 2003, p. 483.

- ^ Finlay 1856, pp. 266–268.

- ^ Pinzelli 2003, pp. 483–486.

- ^ Prelli & Mugnai 2016, p. 44.

- ^ Finlay 1856, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Finlay 1856, pp. 272–274.

- ^ Aksan 2013, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Aksan 2013, p. 100.

Sources

- Aksan, Virginia H. (2013). Ottoman Wars 1700–1870: An Empire Besieged. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-582-30807-7.

- Anderson, R. C. (1952). Naval Wars in the Levant 1559–1853. Princeton: Princeton University Press. OCLC 1015099422.

- Chasiotis, Ioannis (1975). "Η κάμψη της Οθωμανικής δυνάμεως" [The decline of Ottoman power]. In Christopoulos, Georgios A. & Bastias, Ioannis K. (eds.). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος ΙΑ΄: Ο Ελληνισμός υπό ξένη κυριαρχία (περίοδος 1669 - 1821), Τουρκοκρατία - Λατινοκρατία [History of the Greek Nation, Volume XI: Hellenism under Foreign Rule (Period 1669 - 1821), Turkocracy – Latinocracy] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. pp. 8–51. ISBN 978-960-213-100-8.

- Finlay, George (1856). The History of Greece under Othoman and Venetian Domination. London: William Blackwood and Sons. OCLC 1903753.

- Hatzopoulos, Dionysios (2002). Ο τελευταίος Βενετο-Οθωμανικός Πόλεμος, 1714-1718 [The Last Venetian–Ottoman War, 1714-1718]. Athens: Dim. N. Papadimas Editions. ISBN 960-206-502-8.

- Nani Mocenigo, Mario (1935). Storia della marina veneziana: da Lepanto alla caduta della Repubblica [History of the Venetian navy: from Lepanto to the fall of the Republic] (in Italian). Rome: Tipo lit. Ministero della Marina - Uff. Gabinetto.

- Pinzelli, Eric G. L. (2003). Venise et la Morée: du triomphe à la désillusion (1684-1718) [Venice and the Morea: From Triumph to Disillusionment (1684-1718)] (Ph.D. Dissertation) (in French). Aix-en-Provence: Université de Provence.

- Prelli, Alberto; Mugnai, Bruno (2016). L'ultima vittoria della Serenissima: 1716 - L'assedio di Corfù [The Last Victory of the Serenissima: 1716 - The Siege of Corfu] (in Italian). Bassano del Grappa: itinera progetti. ISBN 978-88-88542-74-4.

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1991). Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century. Philadelphia, Massachusetts: The American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-192-2.

- Vakalopoulos, Apostolos E. (1973). Ιστορία του νέου ελληνισμού, Τόμος Δ′: Τουρκοκρατία 1669–1812 – Η οικονομική άνοδος και ο φωτισμός του γένους (Έκδοση Β′) [History of modern Hellenism, Volume IV: Turkish rule 1669–1812 – Economic upturn and enlightenment of the nation (2nd Edition)] (in Greek). Thessaloniki: Emm. Sfakianakis & Sons.

- Conflicts in 1715

- Battles of the Ottoman–Venetian Wars

- Ottoman Peloponnese

- 18th century in Greece

- 1715 in the Ottoman Empire

- 1715 in the Republic of Venice

- Battles in the Peloponnese

- Military history of Corinth

- Prisoner of war massacres

- Massacres committed by the Ottoman Empire

- Massacres in Greece

- Ottoman–Venetian War (1714–1718)