Green Knight

The Green Knight is a character in the 14th century Arthurian poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and the related poem The Greene Knight. He is Bercilak de Hautdesert[1] in Sir Gawain, while The Greene Knight names him "Bredbeddle".[2] The Green Knight later appears as one of Arthur's greatest champions in the fragmentary ballad King Arthur and King Cornwall, where he is called "Bredbeddle".[3] Tolkein described him as being "as vivid and concrete as any image in literature." Other scholars have called him the "most difficult character" to interpret in his most famous poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. His overall role in Arthurian literature includes being a judge and tester of knights, and thus he is both terrifying, friendly, and somewhat mysterious to other characters.[4]

In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Bercilak is transformed into the Green Knight by Morgan le Fay, an enemy of King Arthur, in order to test his court. In the Greene Knight he is transformed by another woman for the same purpose. In both stories he sends his wife to seduce Gawain as a further test. The King Cornwall poem portrays him as an exorcist and one of the most powerful knights in Arthur's court.

The Knight is similar to many other characters in literature, before and after, but is the only one of them to be completely green (at least in the Sir Gawain poem). The meaning of his greenness has puzzled scholars since the discovery of the poem, ranging from views that he is some version of the Green Man (a vegetation deity in medieval art), to a recollection of a figure from Celtic mythology, to a Christian symbol, to the Devil himself.

Etymology

The name 'Bertilak' seems to derive from 'bachlach', a Celtic word meaning 'churl'. Or, it may derive from the word 'Bresalak', meaning 'contentious'. In Old French there is a word 'Bertolais', which translates as 'Bertilak' in the Arthurian tale Merlin. Notably, the 'Bert-' prefix means 'bright', and the '-lak' can mean either 'lake' or "play, sport, fun, etc". 'Hautdesert' probably comes from a mix of both Old French and Celtic words meaning 'High Wasteland' or 'High Hermitage'. It may also have a connection with 'desirete' meaning 'disinherited' (i.e. from the glory of the Round Table).[4]

Role in Arthurian literature

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the Green Knight plays the role of challenger to King Arthur's court. He first appears in the poem during a Christmas feast, riding into the hall seated on his horse. He is described as being completely green: skin, hair, dress, and everything. He is holding a sprig of holly, which the poet points out is green at this time of year. In his other hand he carries a large axe wrapped in a green and gold piece of cloth. Beyond his greenness, he is described as very comely, strong, and well built, and having long hair. The court is shocked and surprised at his appearance. The Knight looks them over and issues a challenge: he will allow one man to strike him with his axe, under the condition that he be allowed to return the blow in a year and a day. After some hesitation and negotiation, it is Gawain who takes the challenge. The Green Knight bends over, even moving aside his hair so that Gawain will have a better chance at his neck. In one blow, Gawain strikes off his head, only to have the strange knight calmly stand, retrieve his head, and tell Gawain to meet him at the Green Chapel at the appointed time.

|

"No, I seek no battle, I assure you truly: |

| — The Green Knight addresses Arthur's Court in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight[5] |

The next time we meet the Knight, he is in the form of Bercilak de Hautedesert, lord of a large castle, who freely invites Gawain in as he journeys to the Green Chapel. Gawain, unaware of his lord's true identity, agrees to a game: the lord will bring Gawain whatever he catches while hunting, if Gawain will give whatever he gains while remaining at the castle. Bercilak goes out into the countryside to hunt for three days, returning each day with his catch for Gawain. Meanwhile, he sends his wife to Gawain's bedroom every morning, in an attempt to seduce the knight. Unaware of this plot, Gawain struggles to remain chaste and keep his bargain with Bercilak. In the end, however, he fails in accepting a green girdle from the lady, and not giving it to Bercilak.

The Green Knight appears again as Gawain approaches the Green Chapel. He is apparently well known throughout the area, as the guide sent to lead Gawain to him grows fearful and runs away as they near the chapel, warning Gawain to do the same in the face of such a dangerous being. When Gawain arrives, the Knight is sharpening his axe. Gawain bends to receive his blow, only to have the green knight feint two blows, then barely nick him on the third. The Knight explains that the three blows were for his three days with his mistress, the third cutting him since he did not return the girdle. He then reveals that he is Bercilak, that he sent his wife purposely to test Gawain, and that Morgan le Fay had given him the ability to be the Green Knight in order to test Arthur's court. He and Gawain part on good terms.

The Greene Knight

The Greene Knight tells basically the same story, except that the knight is only said to be wearing green, not to actually be green himself. The poem also explains a little more of the motives of the Knight's game: The knight is said to have been asked by his wife's mother (not Morgan in this version) to play a joke on Gawain. He agrees because he knows his wife is secretly in love with Gawain, and hopes that he can make a fool of them both by involving them in his game. Again, Gawain falters in his knighthood in accepting a girdle from her, and the Green Knight's purpose is fulfilled in a small sense. In the end, however, he acknowledges Gawain's overall ability and asks to accompany him back to Arthur's court.

King Arthur and King Cornwall

In King Arthur and King Cornwall, the Green Knight, alternately named Sir Bredbeddle, offers to help Arthur fight a mysterious sprite (under the control of King Cornwall) which has entered his chamber. When Arthur asks how he intends to do so, he says he will use a sword from Cologne, a knife from Milan, and an an axe from Denmark. Each of his weapons, however, is broken by the sprite, forcing Bredbeddle to use a sacred text (the Bible) to subdue it. Eventually, after convincing it not to bother Arthur any more, he tries to get it to work for him rather than for Lord Cornwall, in the end gaining complete mastery with the help of his Bible. As a test of his power, he orders the sprite, which he calls Burlow Beane, to fetch a horse for him, which he does. Another knight, named Marramile, tries to control it as well, but fails, and cries to "brother Bredbeddle" for help, as he believes the sprite is the devil himself. The Green Knight quickly regains control, and orders the sprite to steal several of his former master's posessions, then take a sword and strike off his master's head. The story ends as Arthur's knights enjoy the spoils of their victory over this magician.

Similar or derivative characters

Green Knights in other stories

Characters similar to the Green Knight appear in several other works. In Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, for example, Gawain's brother Gareth fights "two brethren whych were called the Grene Knyght and the Rede Knyght". The stories of Saladin feature a certain "Green Knight"; he is a Sicilian warrior in a shield vert and a helmet adorned with stag horns. Saladin had respect for this honourable fighter and tried to make him part of his personal guard.[6] The figure of Al-Khidr (Arabic: الخضر) in the Qur'an is called the "Green Man". He tests Moses three times by doing seemingly evil acts, which are eventually revealed to be noble deeds to prevent greater evils or reveal great goods. Both the Green Knight and Al-Khidr serve as teachers to holy and upright men (Gawain, Moses), who thrice put their faith and obedience to the test. It has been suggested that the character of the Green Knight may be a literary descendant of Al-Khidr, brought to Europe with the Crusaders and blended with Celtic and Arthurian imagery.[7]

Characters fulfilling similar roles

The earliest story with the beheading game element is the Middle Irish tale Bricriu's Feast. The challenger in this story is named "Fear". He challenges many to his game, only to have them run from the return blow, until Cuchulainn takes the challenge. In honor of his courage, this antagonist also feints three blows before letting him go. In the Life of Caradoc, a Middle French narrative embedded in the anonymous First Continuation of Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval, the Story of the Grail, another similar challenge is issued. In this story, a notable difference is that Caradoc's challenger is his father in disguise, come to test his honor. The Girl with the Mule or The Mule Without a Bridle and Hunbaut feature Gawain in beheading-game situations, Hunbaut having an interesting twist: Gawain cuts off the man's head, and then pulls off his magic cloak before he can replace his head, causing his death.[8] There are also several stories in which knights struggle to stave off the advances of voluptuous women, including Yder, the Vulgate cycle, Hunbaut, and The Knight of the Sword. The Green Knight parallel in these stories is a King testing a knight as to whether or not he will remain chaste in extreme circumstances. The woman he sends is sometimes his wife (as in Yder), if he knows that she is unfaithful and will tempt other men. Or, in The Knight of the Sword it is the King's daughter. All of the characters in these stories are portrayed as powerful and frightening, as they usually kill unfaithful knights who fail their tests.[8]

Other characters similar to the Knight do not carry his name, but fulfill similar roles in other Arthurian tales. The Turke and Gowin begins with a Turk entering Arthur's court and asking, "Is there any will, as a brother, To give a buffett and take another?"[9] Gawain accepts the challenge, and is then forced to follow the Turk until he decides to return the blow. Through the many adventures they have together, the Turk, out of respect, rather than returning the blow asks the knight to cut off his head, which Gawain does. The Turk (surviving) then praises Gawain and showers him with gifts. The Carle off Carlile contains a scene in which the Carl, a lord, orders Gawain to strike him with his spear, and bends over to receive the blow.[10] Gawain obliges, the Carl rises, laughing and unharmed, and, unlike in Gawain, no return blow is demanded or given.[8] Among all these stories, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is the only one with a completely green character, and the only one tying Morgan le Fay to the game involved.[8][9]

Significance of the colour green

In English folklore and literature, green has traditionally been used to symbolize nature and its embodied attributes, namely those of fertility and rebirth. Stories of the medieval period portray it as representing love and the amorous in life,[12] and the base, natural desires of man.[13] Green is also known to have signified witchcraft, devilry and evil for its association with the faeries and spirits of early English folklore and for its association with decay and toxicity.[14] The colour, when combined with gold, is sometimes seen as representing the fading away of youth.[15] In the Celtic tradition, green was avoided in clothing for its superstitious association with misfortune and death. The green girdle too, originally worn for protection, is later worn as a symbol of shame and cowardice and is finally adopted as a symbol of honour by the knights of Camelot, signifying a transformation from good to evil and back again displaying both the spoiling and regenerative connotations of the colour green.[4][16] Given these varied and even contradictory interpretations of the colour green, its precise meaning in the poem remains ambiguous.

Interpretations

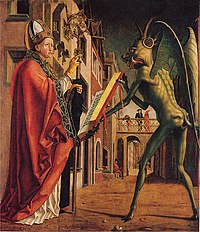

Despite the many characters similar to him, the Green Knight is the first of his parallels to be green.[17] Because of his strange colour, many scholars believe him to be a manifestation of the Green Man figure common in medieval art,[4] or as a representation of both the vitality and fearful unpredictability of nature. The fact that he carries a green holly branch, as well as the comparison of his beard to a bush, has guided many scholars in this direction. The gold entwined in the cloth wrapped around his axe, combined with the green, gives him both a wild and an aristocratic air.[18] Others see him as being an incarnation of the Devil himself.[4] In one interpretation, it is thought that the Green Knight, as the "Lord of Hades," has come to challenge the noble knights of King Arthur's court. Sir Gawain, the bravest of the knights, therefore proves himself the equal to Hercules in challenging the Knight, tying the story to ancient Greek mythology.[14] Another possible interpretation of the Green Knight is to view him as a fusion of these two deities, at once representing both good and evil and life and death as self-proliferating cycles. This interpretation embraces the positive and negative attributes of the colour green and ties in with the enigmatic motif of the poem.[4] The description of the Green Knight upon his entrance to Arthur's Court as "from neck to loin… strong and thickly made" is viewed by other scholars as homoerotic.[19]

The Green Chapel

In the Gawain poem, when the Knight is beheaded, he tells Gawain to meet him at the Green Chapel, saying that all nearby know where it is. Indeed, the guide which is to bring Gawain from Bertilak's castle grows very fearful, and begs Gawain to turn back, as all around fear the Green Knight. The final meeting at the Green Chapel has led many scholars to draw religious connections. The Knight in this case fulfills a priestly role with Gawain as a Confessor. The Green Knight ultimately, in this interpretation, judges Gawain to be a worthy knight, and lets him live. In this way, the Green Knight can be a priest, God, and judge all at once. The Chapel, however, is just as difficult to interpret as the Knight himself. Despite its being a chapel, it is seen in Gawain's eyes as an evil place, foreboding, "the most accursed church," "the place for the Devil to recite matins." However, when the mysterious Knight allows Gawain to live, Gawain immediately assumes the role of confessor to a priest or judge, as would be normal in an actual church. The Green Chapel may also be related to tales of fairy hills or knolls of earlier Celtic literature. Some scholars have wondered whether 'Hautdesert' refers to the Green Chapel, as it means 'High Hermitage', but such a connection is doubted among most scholars.[4] In the Greene Knight poem, Sir Bredbeddle's living-place is described as "the castle of hutton," leading some scholars to believe it to be the Hutton Manor House in Somersetshire.[20]

Jack in the green

The Green Knight is also compared to the English holiday figure Jack in the green. Jack is part of a May Day holiday tradition all over England, but his connection to the Knight is found mainly in the Derbyshire traditions of Castleton Garlanding. Jack in the green marches into the town on a horse, dressed in green and wearing a garland of leaves and flowers that covers his entire upper body. On the top of the garland is a quane, or a group of bright flowers. At the end of a ceremony, the quayne is taken off the garland and placed at the top of the church tower. Due to the nature imagery associated with the Green Knight, scholars have seen the ceremony as possibly deriving from his famous beheading in the Gawain poem, the quane removal being symbolic of the loss of the knight's head.[21]

See also

Notes

- ^ An alternate spelling in some translations is "Bertilak" or "Bernlak"

- ^ Hahn, Thomas (2000). "The Greene Knight". In Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales, p. 314. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications. ISBN 1-879288-59-1.

- ^ Hahn, Thomas (2000). "King Arthur and King Cornwall". In Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales, p. 427. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications. ISBN 1-879288-59-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g The Idea of the Green Knight, Lawrence Besserman, ELH, Vol. 53, No. 2. (Summer, 1986), pp. 219-239. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Medieval Period. Vol. 1. ed. Joseph Black, et al. Toronto: Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-609-X Intro pg. 235

- ^ Richard, Jean. An Account of the Battle of Hattin Referring to the Frankish Mercenaries in Oriental Moslem States Speculum 27.2 (1952) pp. 168-177.

- ^ Lasater, Alice E. (1974). Spain to England: A Comparative Study of Arabic, European, and English Literature of the Middle Ages. University Press of Mississippi.

- ^ a b c d Brewer, Elisabeth. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight : sources and analogues. 1992

- ^ a b Hahn, Thomas (2000). "The Turke and Sir Gawain". In Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications. ISBN 1-879288-59-1. Online: The Turke and Sir Gawain.

- ^ Hahn, Thomas (2000). "The Carle of Carlisle". In Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications. ISBN 1-879288-59-1. Online: The Carle of Carlisle.

- ^ Why the Devil Wears Green Author: D. W. Robertson, Jr. Journal: Modern Language Notes Pub.: 1954-11 Volume: 69 Issue: 7 Pages: 470-472

- ^ Symbolic Green: A Time-Honored Characterizing Device in Spanish Literature Vernon A. Chamberlin Hispania, Vol. 51, No. 1 (Mar., 1968), pp. 29-37

- ^ The Green and the Gold: The Major Theme of Gawain and the Green Knight William Goldhurst College English, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Nov., 1958), pp. 61-65 doi:10.2307/372161

- ^ a b Williams, Margaret. The Pearl Poet, His Complete Works. Random House, 1967.

- ^ Gawain and the Green Knight John S. Lewis College English, Vol. 21, No. 1 (Oct., 1959), pp. 50-51

- ^ Why The Devil Wears Green, D. W. Robertson Jr., Modern Language Notes, Vol. 69, No. 7. (Nov., 1954), pp. 470-472. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Krappe, A. H. "Who Was the Green Knight?" Speculum. (Apr 1938) 13.2 pgs. 206-215

- ^ The Green and the Gold: The Major Theme of Gawain and the Green Knight William Goldhurst College English, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Nov., 1958), pp. 61-65 doi:10.2307/372161

- ^ Zeikowitz, Richard E. "Befriending the Medieval Queer: A Pedagogy for Literature Classes" College English Special Issue: Lesbian and Gay Studies/Queer Pedagogies. 65.1 (2002) 67-80.

- ^ Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and the Stanley Family of Stanley, Storeton, and Hooton Author: Edward Wilson Journal: The Review of English Studies Pub.: 1979-08 Volume: 30 Issue: 119 Pages: 308-316

- ^ A Re-Examination of the Castleton Garlanding Author: Michael M. Rix Journal: Folklore Pub.: 1953-06 Volume: 64 Issue: 2 Pages: 342-344

References

- Hahn, Thomas (2000). Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications. ISBN 1-879288-59-1.