Harpsichord

A harpsichord is any of a family of European keyboard instruments, including the large instrument currently called a harpsichord, but also the smaller virginals, the muselar or muselaar virginals and the spinet. All these instruments generate sound by plucking a string rather than striking one, as in a piano or clavichord.

How harpsichords work

Although harpsichords vary greatly in size and shape, they all have the same basic functional arrangement. The player presses a key ((1) in Fig. 1 below), causing the far end of the key to rise. This in turn lifts the jack, a tongue of wood (17), to which is attached a small plectrum (a bit of quill or plastic), which on being lifted plucks the string (8). When the key is released by the player, the far end returns to its rest position and the jack is lowered. The plectrum, being mounted on a tongue that can swivel backwards, can then return beneath the string without plucking it again. As the key settles into its rest position, the string vibrations are halted by a damper, a bit of felt attached to the jack.

These basic principles are explained in more detail below.

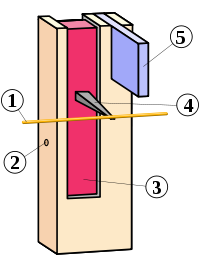

Figure 1

- The keylever (fig. 1, 1) is a simple pivot, which rocks on a balance pin (fig. 1, 24) passing through a hole drilled through it.

- The jack is a thin, rectangular piece of wood which sits upright on the end of the keylever, held in place by the registers (upper and lower) which are two long pieces of wood with holes through which the jacks can pass. The upper and lower registers are shown in Fig. 1 as 7 and 22.

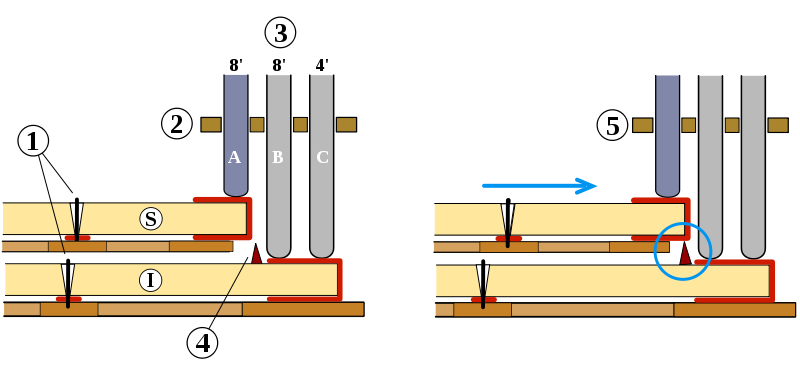

Figure 2

- In the jack, a plectrum (fig. 2, 4) juts out almost horizontally (normally the plectrum is angled upwards a tiny amount) and passes just under the string (fig. 2, 4). Historically, plectra were normally made of crow quill or leather, though most modern harpsichords use a plastic (delrin or celcon) instead.

- When the front of the key is pressed (Fig. 1, 1), the back of the key rises, the jack is lifted, and the plectrum plucks the string (fig. 3, B-C).

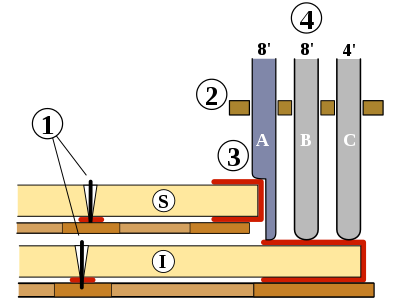

Figure 3

- When the key is lowered, the jack falls back down under its own weight, and the plectrum pivots backwards to allow it past the string (fig. 3, D). This is made possible by having the plectrum held in a tongue (fig. 3, 6), which is attached with a hinge (fig. 3, 7) and a spring (fig. 3, 8) to the body of the jack.

- At the top of the jack, a damper of felt (fig. 3, 3) sticks out and keeps the string from vibrating when the key is not depressed.

- If the player strikes a key too vigorously, there is a risk that the jack will pop up so high as to fall out of its register. This is prevented by the padded jack rail (fig. 1, 6).

Strings and soundboard

Simply plucking the strings would produce a very feeble sound. The full sonority of the harpsichord arises because the strings pass over a bridge (fig. 1, 9), which provides a sharp edge supporting one end of their vibrating length. The bridge is firmly attached to a soundboard (fig. 1, 14), a slender panel of wood usually made of spruce or (in Italian harpsichords) cypress. The soundboard efficiently transmits the vibrations of the strings to the air, making them fully audible.

The strings must be held at the proper tension to sound the correct note. At one end, generally closest to the keyboard, they are passed around tuning pins (fig. 1, 4), which may be rotated with an appropriate wrench (tuning hammer) to achieve the correct tension. The tuning pins are embedded in the pinblock or wrestplank (fig. 1, 23), a sturdy plank that grips them firmly. The other ends of the strings are held firmly by small, static hitchpins (fig. 1, 10).

Multiple choirs of strings

It is not unusual for a harpsichord to have exactly one string per note. However, there are several reasons why it is considered desirable to have more.

- When there are two choirs of strings at the same length, it is possible to give them different tonal qualities and thus increase the variety of sound that the harpsichord can produce. This is done by having one plucked close to the nut (the bridge-like device that terminates the sounding length of the strings), the other farther away. Plucking close to the nut emphasizes the higher harmonics, producing a "nasal" sound quality.

- When two strings are carefully tuned to be the same pitch, or an octave apart, and are plucked simultaneously (by a single keystroke), the ear will hear a single note, louder and enriched by virtue of being sounded by two differently arranged strings. The quality distinction is particularly noticeable when the one string is an octave higher or lower then the other.

Thus, in describing a harpsichord, it is customary to specify its choirs of strings, often called its disposition. Strings at eight foot pitch sound at the normal expected pitch, strings at four foot pitch sound an octave higher, and similarly for the rare 16-foot pitch (one octave lower) and two-foot pitch (two octaves higher).

When there are multiple choirs of strings, it is desirable for the player to be able to control which ones are played at any given time. This is generally done by having multiple sets of jacks (one per string), "turning off" a choir of strings by moving the upper register (through which the jacks slide) sideways a bit, so that their plectra no longer touch the strings.

In simpler instruments, this function was performed directly by hand, but as the harpsichord evolved various inventions arose making it easier to change the registration, for example with levers next to the keyboard, knee levers, or pedals.

Particular flexibility in selecting the strings to be played could be obtained in instruments that had more than one manual (keyboard), since each manual could control a particular set of the plucking of a particular set of strings. In addition, makers often produced arrangements whereby the notes of one manual could optionally be sounded with the other manual. The most flexible system was the French shove coupler, in which the lower manual could slide forward and backward, and in the backward position "dogs" attached to the upper surface of the lower manual would engage the lower surface of the upper manual's keys, causing them to play. Depending on choice of keyboard and coupler position, the player could select the set of jacks labeled in fig. 4 as A, or B and C, or all three.

Figure 4

The English dogleg jack system was less flexible, in that the manuals were immobile. The dogleg shape of the set of jacks labeled A in fig. 5 permitted A to be played by either keyboard, but the lower manual necessarily played all three sets, and could not play just B and C as in the French shove coupler.

Figure 5

Curiously, the use of multiple manuals in a harpsichord was not originally for the purpose of flexibility in choosing which strings would sound, but rather for transposition; for discussion see History below.

The case

The case holds in position all of the important structural members: pinblock, soundboard, hitchpins, keyboard, and the jack action. It usually includes a solid bottom, and also internal bracing to maintain its form without warping under the tension of the strings. Cases varied greatly in weight and sturdiness: Italian harpsichords often used very light construction, while heavier construction is found in the later Flemish instruments and those derived from them (see History, below).

The case also gives the harpsichord its external appearance and protects the instrument. A harpsichord of the 18th century is, in a sense, a kind of furniture, as it stands alone on legs and is usually styled in a manner similar to the furniture of its place and time. But this conception emerged only gradually. Early Italian instruments were so light in construction that they were treated rather like violins: kept for storage in protective outer cases and played by extracting them from their cases and placing them on a table.[1] (Such tables were often quite high, since until the late 18th century people usually played standing up.[2]) Eventually, harpsichords came to be built with just a single case, though a curious intermediate stage also existed: the "false inner-outer", which for purely esthetic reasons was built to look as if the outer case contained an inner one, in the old style.[3].

Even after harpsichords had become self-encased objects, they often were supported by separate stands, and only gradually came to have their own legs.

In the fully evolved instrument, there is lid that can be raised, a cover for the keyboard, and a stand for holding music in place.

Harpsichords were decorated in a great many ways: plain buff paint (e.g. some Flemish instruments), paper printed with patterns, leather or velvet coverings, chinoiserie, and occasionally highly elaborate painted artwork.[4]

Variants

While the terms used to denote various members of the family have been quite standardized today, in the harpsichord's heyday, this was not the case.

Harpsichord

In modern usage, a harpsichord can either mean all the members of the family, or more specifically, the grand-piano-shaped member, with a vaguely triangular case accommodating long bass strings at the left and short treble strings at the right; characteristically, the profile is more elongated than that of a modern piano, with a sharper curve to the bentside.

Virginals

The virginal or virginals is a smaller and simpler rectangular form of the harpsichord (that looks somewhat like a clavichord), with only one string per note running parallel to the keyboard on the long side of the case. Identified by this name by 1460, it was played either in the lap, or more commonly, rested on a table.[5]While the name apparently comes from the same root as the adjective "virginal", the reason for this name is obscure. Note that the word "virginal" in Elizabethan times was often used to designate any kind of harpsichord; thus the masterworks of William Byrd and his contemporaries were often played on full-size, Italian or Flemish-style harpsichords and not just on the virginals as we call it today. Virginals are described either as spinet virginals (the usual type) or muselar virginals.

Spinet virginals

In spinet virginals, the keyboard is placed on the left, and the strings are plucked at one end as in other members of the harpsichord family. This is the more common arrangement, and an instrument described simply as a "virginal" is likely to be a spinet virginal.

Muselar virginals

In muselar virginals, or muselars, the keyboard is placed to the right or in the center so that the strings are plucked in the middle of their sounding length. This gives a warm rich and fundamental sound (somewhat reminiscent of a square wave), but at a price: the action for the left hand is inevitably placed in the middle of the instrument's sounding board, with the result that any mechanical noise from this action is amplified. An 18th century commentator (Van Blankenberg, 1739) said that muselars "grunt in the bass like young pigs". In addition to mechanical noise, the central plucking point in the bass makes repetition difficult, because the motion of the still-sounding string interferes with the ability of the plectrum to connect again. Thus the muselar was better suited to chord-and-melody music without complex left hand parts.

Muselars were popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, but they fell out of use in the 18th century.

Spinet

A harpsichord with the strings set at an angle to the keyboard (usually of about 30 degrees) is called a spinet. In such an instrument, the strings are too close to fit the jacks between them in the normal way; instead, the strings are arranged in pairs, the jacks are placed in the large gaps between pairs, and they face in opposite directions, plucking the strings adjacent to the gap.

Clavicytherium

A clavicytherium is a harpsichord that is vertically strung. The same space-saving principle was later embodied in the upright piano. The vertical form was made possible by arranging the shape of the jacks so that the body curved like a quarter circle.[6]

Curiously, some of the earliest harpsichords for which we have evidence are clavicithyria. One surviving example from the late 15th century is kept at the Royal College of Music in London).[7] The clavicytherium may have been one of the candidates for harpsichord actions during the early days of the instrument, when alternatives vied (see below, History), but ultimately was almost entirely defeated by the standard horizontal harpsichord, which has the advantage of being able to rely on the direct force of gravity to return the jacks to their rest position.

However, clavicytheria continued to be made from time to time throughout the historical period. In the 18th century particularly fine clavicytheria were made by Albertus Delin, a Flemish builder.[8].

Other

Several harpsichords with heavily modified keyboards, such as the archicembalo, were built in the 16th century to accommodate variant tuning systems demanded by compositional practice and theoretical experimentation.

Compass and Pitch range

Generally, earlier harpsichords have smaller ranges and later ones larger, though there are frequent exceptions. In general, the largest harpsichords have a range of just over five octaves and the smallest have under four. Usually, the shortest keyboards were given extended range in the bass using the method of the "short octave". Tuning Pitch in nowadays' practice is taken often at a=415 Hz, a semitone below modern standard concert pitch of a=440 Hz. An accepted exception is for French baroque repertoir which is often performed from a=392 Hz, yet again one semitone lower. No doubt this is overly simplified, but common practice. Historically, tuning would commence on c or f.

History

- Main article: History of the harpsichord

The harpsichord was most likely invented in the late Middle Ages. By the 1500's, harpsichord makers in Italy were making lightweight instruments with low string tension. A different approach was taken in Flanders starting in the late 1500s, notably by the Ruckers family. Their harpsichords used a heavier construction and produced a more powerful and distinctive tone. They included the first harpsichords with two keyboards, used for transposition.

The Flemish instruments served as the model for 18th century harpsichord construction in other nations. In France, the double keyboards were adapted to control different choirs of strings, making a musically more flexible instrument. Instruments from the peak of the French tradition, by makers such as the Blanchet family and Pascal Taskin, are among the most widely admired of all harpsichords, and are frequently used as models for the construction of modern instruments. In England, the Kirkman and Shudi firms produced sophisticated harpsichords of great power and sonority. German builders extended the sound repertoire of the instrument by adding sixteen foot and two foot choirs; these instruments have recently served as models for modern builders.

Toward the end of the 18th century, the harpsichord was supplanted by the piano and disappeared from view for most of the 19th century. 20th century efforts to revive the harpsichord initially involved much importation of piano technology, in the form of heavy strings and metal frames. Starting in mid century, the contruction of modern harpsichord underwent a major change, when builders such as Frank Hubbard, William Dowd, and Martin Skowroneck established a new building tradition in which modern instruments are constructed to resemble historical instruments. Harpsichords of this type dominate the current scene.

Music for the harpsichord

Historic

The first music written specifically for solo harpsichord came to be published around the early 16th century. Composers who wrote solo harpsichord music were numerous during the whole Baroque era in Italy, Germany and, above all, France. Favourite genres for sole harpsichord composition included the dance suite, the fantasia, and the fugue. Besides solo works, the harpsichord was widely used for accompaniment in the basso continuo style (a function it maintained in opera even into the 19th century). Well into the 18th century, the harpsichord was considered to have advantages and disadvantages with respect to the piano.

After the baroque

Through the 19th century, the harpsichord was ignored by composers, the piano having supplanted it. In the 20th century, however, with increasing interest in early music and composers seeking new sounds, pieces began to be written for it once more. Concertos for the instrument were written by Francis Poulenc (the Concert champêtre, 1927-28), Manuel de Falla and, later, by Henryk Górecki, Philip Glass and Roberto Carnevale. Bohuslav Martinů wrote both a concerto and a sonata for it, and Elliott Carter's Double Concerto is for harpsichord, piano and two chamber orchestras. In chamber music, György Ligeti has written a small number of solo works for the instrument (including "Continuum") while Henri Dutilleux's "Les Citations" (1991) is a piece for harpsichord, oboe, double bass and percussions. Both Dmitri Shostakovich (Hamlet, 1964) and Alfred Schnittke (Symphony No.8, 1998) used the harpsichord as part of the orchestral texture. More recently harpsichordist Hendrik Bouman has composed in the 17th and 18th century style 75 pieces of which 37 compositions are for solo harpsichord, 2 compositions are of harpsichord concerti, 2 compositions feature obbligato harpsichord and 36 composition include harpsichord in the basso continuo in his chamber music and orchestral music.

Popular music

Like almost all instruments of classical music, the harpsichord has been adapted for popular work. The number of such uses is vast; for a partial list, see harpsichord in popular culture.

Nomenclature

The type of instrument now usually called a harpsichord in English is generally called a clavicembalo or simply cembalo in Italian, and this last word is generally used in German as well. The typical French word is clavecin (in historical sources, sometimes the word epinette is used in a global sense, meaning any instrument with a harpsichord-like action), while the Dutch word is klavecimbel.

Notes

References

- Boalch, Donald H. (1995) Makers of the Harpsichord and Clavichord, 1440-1840, 3rd edition, with updates by Andreas H. Roth and Charles Mould, Oxford University Press. A catalogue, originating with work by Boalch in the 1950's, of all extant historical instruments.

- Hubbard, Frank (1967) Three Centuries of Harpsichord Making, 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; ISBN 0-674-88845-6. An authoritative survey by a leading builder of how early harpsichords were built and how the harpsichord evolved over time in different national traditions.

- Kottick, Edward (2003) A History of the Harpsichord, Indiana University Press. An extensive survey by a leading contemporary scholar.

- O'Brien, Grant (1990) Ruckers, a harpsichord and virginal building tradition, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521365651. Covers the innovations of the Ruckers family, the founders of the Flemish tradition.

- Russell, Raymond (1959) The Harpsichord and Clavichord London: Faber and Faber.

- Skowroneck, Martin (2003) Cembalobau: Erfahrungen und Erkenntnisse aus der Werkstattpraxis = Harpsichord construction: a craftsman's workshop experience and insight. Bergkirchen: Edition Bochinsky, ISBN 3-932275-58-6. A study (written in English and German) of harpsichord building by a leading figure in the modern revival of historically authentic methods of building.

- Zuckermann, Wolfgang (1969) The Modern Harpsichord, 20th-century instruments and their makers. October House Inc.

External links

- A brief history of the harpsichord

- Harpsichord maker Carey Beebe has a comprehensive website about harpsichords

- A harpsichord site with images

- Hear the sound of various harpsichords

- Extensive source of harpsichord information

- HPSCHD-L is a mailing list devoted to early stringed keyboard instruments.

- HarpsichordPhoto is a site devoted to photographs of early stringed keyboard instruments.

- Ernest Miller Harpsichords: Creations in the French and Flemish Traditions.

- Interview with harpsichord builder Jack Peters.