Telephone

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. |

Look up telephone in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

|

|

|

The telephone is a telecommunications device which is used to transmit and receive sound (most commonly speech). Most telephones operate through transmission of electric signals over a complex telephone network which allows almost any phone user to communicate with almost anyone.

Basic principle

The telephone handles two types of information: signals and voice, at different times on the same twisted pair of wires. The signaling equipment consists of a bell to alert the user of incoming calls, and a dial to enter the phone number for outgoing calls. A calling party wishing to speak to another telephone will pick up the handset, thus operating the switch hook, which puts the telephone into active state or off hook with a resistance short across the wires, causing current to flow. The telephone exchange detects the DC current, attaches a digit receiver, and sends dial tone to indicate readiness. The user pushes the number buttons, which are connected to a tone generator inside the dial, which generates DTMF tones. The exchange connects the line to the desired line and alerts that line.

When a phone is inactive (on hook), its bell, beeper, flasher or other alerting device is connected across the line through a capacitor. The inactive phone does not short the line, thus the exchange knows it is on hook and only the bell is electrically connected. When someone calls this phone, the telephone exchange applies a high voltage pulsating signal, which causes the sound mechanism to ring, beep or otherwise alert the called party. When that user picks up the handset, the switchhook disconnects the bell, connects the voice parts of the telephone, and puts a resistance short on the line, confirming that the phone has been answered and is active. Both lines being off hook, the signaling job is complete. The parties are connected together and may converse using the voice parts of their telephones.

The voice parts of the telephone are in the handset, and consist of a transmitter (often called microphone) and a receiver. The transmitter, powered from the line, puts out an electric current which varies in response to the acoustic pressure waves produced by the voice. The resulting variations in electric current are transmitted along the telephone line to the other phone, where they are fed into the coil of the receiver, which is a miniature loudspeaker. The varying electric current in the coil causes it to move back and forth, reproducing the acoustic pressure waves of the transmitter.

When a party "hangs up" (puts the handset on the cradle), DC current ceases to flow in that line, thus signaling to the exchange switch to disconnect the telephone call.

History

Credit for inventing the electric telephone remains in dispute. Antonio Meucci, Johann Philipp Reis, Alexander Graham Bell, and Elisha Gray, among others, have all been credited with the invention.

The early history of the telephone is a confusing morass of claim and counterclaim, which was not clarified by the huge mass of lawsuits which hoped to resolve the patent claims of individuals. The Bell and Edison patents, however, were forensically victorious and commercially decisive.

Early development

The following is a brief summary of the development of the telephone:

- 28 December 1871—Antonio Meucci files a patent caveat (n.3335) in the U.S. Patent Office titled "Sound Telegraph", describing communication of voice between two people by wire.

- 1874—Meucci, after having renewed the caveat for two years, fails to find the money to renew it. The caveat lapses.

- 6 April 1875—Bell's U.S. Patent 161,739 "Transmitters and Receivers for Electric Telegraphs" is granted. This uses multiple vibrating steel reeds in make-break circuits.

- 11 February 1876—Gray invents a liquid transmitter for use with a telephone but does not build one.

- 14 February 1876—Elisha Gray files a patent caveat for transmitting the human voice through a telegraphic circuit.

- 14 February 1876—Alexander Bell applies for the patent "Improvements in Telegraphy", for electromagnetic telephones using undulating currents.

- 19 February 1876—Gray is notified by the U.S. Patent Office of an interference between his caveat and Bell's patent application. Gray decides to abandon his caveat.

- 7 March 1876—Bell's U.S. patent 174,465 "Improvement in Telegraphy" is granted, covering "the method of, and apparatus for, transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically … by causing electrical undulations, similar in form to the vibrations of the air accompanying the said vocal or other sound."

- 30 January 1877—Bell's U.S. patent 186,787 is granted for an electro-magnetic telephone using permanent magnets, iron diaphragms, and a call bell.

- 27 April 1877—Edison files for a patent on a carbon (graphite) transmitter. The patent 474,230 was granted 3 May 1892, after a 15 year delay because of litigation. Edison was granted patent 222,390 for a carbon granules transmitter in 1879.

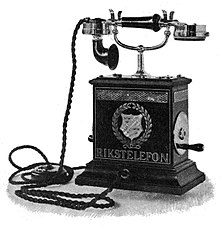

Early commercial instruments

Early telephones were technically diverse. Some used a liquid transmitter, which was dangerous, inconvenient, and soon went out of use. Some were dynamic: their diaphragm wriggled a coil of wire in the field of a permanent magnet or vice versa. This kind survived in small numbers through the 20th century in military and maritime applications where its ability to create its own electrical power was crucial. Most, however, used the Edison/Berliner carbon transmitter, which was much louder than the other kinds, even though it required an induction coil, actually acting as an impedance matching transformer to make it compatible to the impedance of the line. The Edison patents kept the Bell monopoly viable into the 20th century, by which time the network was more important than the instrument anyway.

Early telephones were locally powered, using a dynamic transmitter or else powering the transmitter with a local battery. One of the jobs of outside plant personnel was to visit each telephone periodically to inspect the battery. During the 20th century, "common battery" operation came to dominate, powered by "talk battery" from the telephone exchange over the same wires that carried the voice signals. Late in the century, wireless handsets brought a revival of local battery power.

Early telephones had one wire for both transmitting and receiving of audio, with ground return as used in telegraphs. The earliest dynamic telephones also had only one opening for sound, and the user alternately listened and spoke (rather, shouted) into the same hole. Sometimes the instruments were operated in pairs at each end, making conversation more convenient but were more expensive.

At first, the benefits of an exchange were not exploited. Telephones instead were leased in pairs to the subscriber, who had to arrange telegraph contractors to construct a line between them, for example between his home and his shop. Users who wanted the ability to speak to several different locations would need to obtain and set up three or four pairs of telephones. Western Union, already using telegraph exchanges, quickly extended the principle to its telephones in New York City and San Francisco, and Bell was not slow in appreciating the potential.

Signalling began in an appropriately primitive manner. The user alerted the other end, or the exchange operator, by whistling into the transmitter. Exchange operation soon resulted in telephones being equipped with a bell, first operated over a second wire and later with the same wire using a condenser. Telephones connected to the earliest Strowger automatic exchanges had seven wires, one for the knife switch, one for each telegraph key, one for the bell, one for the push button and two for speaking.

Rural and other telephones that were not on a common battery exchange had a "magneto" or hand cranked generator to produce a high voltage alternating signal to ring the bells of other telephones on the line and to alert the operator.

In the 1890s a new smaller style of telephone was introduced, packaged in three parts. The transmitter stood on a stand, known as a "candlestick" for its shape. When not in use, the receiver hung on a hook with a switch in it, known as a "switchhook." Previous telephones required the user to operate a separate switch to connect either the voice or the bell. With the new kind, the user was less likely to leave the phone "off the hook". In phones connected to magneto exchanges, the bell, induction coil, battery and magneto were in a separate "bell box." In phones connected to common battery exchanges, the bell box was installed under a desk, or other out of the way place, since it did not need a battery or magneto.

Cradle designs were also used at this time, having a handle with the receiver and transmitter attached, separate from the cradle base that housed the magneto crank and other parts. They were larger than the "candlestick" and more popular.

Disadvantages of single wire operation such as crosstalk and hum from nearby AC power wires had already led to the use of twisted pairs and, for long distance telephones, four-wire circuits. Users at the beginning of the 20th century did not place long distance calls from their own telephones but made an appointment to use a special sound proofed long distance telephone booth furnished with the latest technology.

What turned out to be the most popular and longest lasting physical style of telephone was introduced in the early 20th century, including Bell's Model 102. A carbon granule transmitter and electromagnetic receiver were united in a single molded plastic handle, which when not in use sat in a cradle in the base unit. The circuit diagram of the Model 102 shows the direct connection of the receiver to the line, while the transmitter was induction coupled, with energy supplied by a local battery. The coupling transformer, battery, and ringer were in a separate enclosure. The dial switch in the base interrupted the line current by repeatedly but very briefly disconnecting the line 1-10 times for each digit, and the hook switch (in the center of the circuit diagram) permanently disconnected the line and the transmitter battery while the handset was on the cradle.

After the 1930s, the base also enclosed the bell and induction coil, obviating the old separate bell box. Power was supplied to each subscriber line by central office batteries instead of a local battery, which required periodic service. For the next half century, the network behind the telephone became progressively larger and much more efficient, but after the dial was added the instrument itself changed little until touch tone replaced the dial in the 1960s.

Digital telephony

The Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN) has gradually evolved towards digital telephony which has improved the capacity and quality of the network. End-to-end analog telephone networks were first modified in the early 1960s by upgrading transmission networks with T1 carrier systems. Later technologies such as SONET and fiber optic transmission methods further advanced digital transmission. Although analog carrier systems existed, digital transmission made it possible to significantly increase the number of channels multiplexed on a single transmission medium. While today the end instrument remains analog, the analog signals reaching the aggregation point (Serving Area Interface (SAI) or the central office (CO) ) are typically converted to digital signals. Digital loop carriers (DLC) are often used, placing the digital network ever closer to the customer premises, relegating the analog local loop to legacy status.

IP telephony

Internet Protocol (IP) telephony (also known as internet telephony) is a service based on Voice over IP (VoIP), a disruptive technology that is rapidly gaining ground against traditional telephone network technologies. In Japan and South Korea up to 10% of subscribers, as of January 2005, have switched to this digital telephone service. A January 2005 Newsweek article suggested that internet telephony may be "the next big thing." [1]

As of 2006 many VoIP companies offer service to consumers and businesses.

IP telephony uses a broadband internet connection to transmit conversations as data packets. In addition to replacing POTS(plain old telephone service), IP telephony is also competing with mobile phone networks by offering free or lower cost connections via WiFi hotspots. VoIP is also used on private wireless networks which may or may not have a connection to the outside telephone network.

Usage

By the end of 2006, there were a total of nearly 4 billion mobile and fixed line subscribers and over 1 billion Internet users worldwide. This included 1.27 billion fixed line subscribers and 2.68 billion mobile subscribers. [2]

Telephone operating companies

In some countries, many telephone operating companies (commonly abbreviated to telco in American English) are in competition to provide telephone services. Some of them are included in the following list. However, the list only includes facilities based providers and not companies which lease services from facilities based providers in order to serve their customers.

Patents

- US 174,465 -- Telegraphy (Bell's first telephone patent) -- Alexander Graham Bell

- US 186,787 -- Electric Telegraphy (permanent magnet receiver) -- Alexander Graham Bell

- US 474,230 -- Speaking Telegraph (graphite transmitter) -- Thomas Edison

- US 203,016 -- Speaking Telephone (carbon button transmitter) -- Thomas Edison

- US 222,390 -- Carbon Telephone (carbon granules transmitter) -- Thomas Edison

- US 485,311 -- Telephone (solid back carbon transmitter) -- Anthony C. White (Bell engineer) This design was used until 1925 and installed phones were used until the 1940s.

- US 3,449,750 -- Duplex Radio Communication and Signalling Appartus -- G. H. Sweigert

- US 3,663,762 -- Cellular Mobile Communication System -- Amos Edward Joel (Bell Labs)

- US 3,906,166 -- Radio Telephone System (DynaTAC cell phone) -- Martin Cooper et al. (Motorola)

See also

References

- Coe, Lewis (1995), The Telephone and Its Several Inventors: A History, McFarland, North Carolina, 1995. ISBN 0-7864-0138-9

- Evenson, A. Edward (2000), The Telephone Patent Conspiracy of 1876: The Elisha Gray - Alexander Bell Controversy, McFarland, North Carolina, 2000. ISBN 0-7864-0883-9

- Baker, Burton H. (2000), The Gray Matter: The Forgotten Story of the Telephone, Telepress, St. Joseph, MI, 2000. ISBN 0-615-11329-X

- Huurdeman, Anton A. (2003), The Worldwide History of Telecommunications, IEEE Press and J. Wiley & Sons, 2003. ISBN 0-471-20505-2

- Josephson, Matthew (1992), Edison: A Biography, Wiley, 1992. ISBN 0-471-54806-5

- Bruce, Robert V. (1990), Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1990.

Further reading

- Robert Sobel, The Entrepreneurs: Explorations Within the American Business Tradition (Weybright & Talley 1974), ISBN 0-679-40064-8.

- Kenneth P. Todd, A Capsule History of the Bell System

External links

- 1911 Britannica "Telephone" article

- Template:Dmoz

- Mobile Phones- Specifications in a number of languages