Arghun

You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|date=Dec 2007. The references and their numbering are confusing|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

Arghun Khan (c. 1258 – March 7,[1] 1291) was the fourth ruler of the Mongol empire's Ilkhanate division in Iran from 1284 to 1291. He was the son of Abaqa Khan, and like his father, was a devout Buddhist (although pro-Christian). He was known for sending several embassies to Europe in an attempt to form an alliance against the Muslims in the Holy Land. He is also reputed to have oppressed Muslims forcibly during his rule.

His wife, Bulughan (also Buluqhan Khatun, Bolgana, Bulughan, or "Zibeline"), gave birth to his two sons Ghazan and Öljeitü, both of whom later succeeded him and eventually converted to Islam.

Arghun had Öljeitü baptized as a Christian at birth, and gave him the name "Nicholas" after Pope Nicholas IV.[2] According to the Dominican missionary Ricoldo of Montecroce, he was "a man given to the worst of villainy, but for all that a friend of the Christians".[3]

One of the sisters of Arghun, Oljalh, was married to the Georgian prince Wakhtang III.[4]

Rule

Arghun was a Buddhist, but showed great tolerance for all faiths. He even allowed Muslims to be judged under Koranic law. His minister of finance, Sa'ad ad dawla, was a Jew. Sa'ad was effective in restoring order to the Ilkhanate's government, in part by aggressively denouncing the abuses of the Mongol military leaders.[5]

Internal conflicts

Arghun had to deal with few conflicts with his fellow Mongols, and his reign was comparetively peacefull. He had to fight a brief campaign against the Chagatai Khanate in Khorasan. In 1289-1290, he had to deal with an upheaval of the Oirat emir Nauruz, which had to flee to Transoxonia.

In 1290, he repelled an invasion force of the Golden Horde in the area of the Caucasus led by Tole Buqa.

Relations with Christian powers

Arghun was one of a long line of Mongol rulers who endeavoured to established a Franco-Mongol alliance with the Europeans, against their common enemies the Egyptian Mamluks. Arghun sent multiple emissaries, and promised that if Jerusalem were conquered, he would have himself baptised, and would return Jerusalem to the Christians. However, according to Prawdin, Western Europe was no longer as interested in the Crusades, and the mission was ultimately fruitless.[6]

First mission to the Pope (1285)

In 1285, Arghun sent an embassy and a letter to Pope Honorius IV, a Latin translation of which is preserved in the Vatican.[7] The embassy was accompanied by a Genoese Italian named Tommaso Banchrinus ("The Banker") de' Anfossi.[8] Arghun's letter mentioned the links that Arghun's family had to Christianity, and proposed a combined military conquest of Muslim lands:[9]

"As the land of the Muslims, that is, Syria and Egypt, is placed between us and you, we will encircle and strangle ("estrengebimus") it. We will send our messengers to ask you to send an army to Egypt, so that us on one side, and you on the other, we can, with good warriors, take it over. Let us know through secure messengers when you would like this to happen. We will chase the Saracens, with the help of the Lord, the Pope, and the Great Khan."

— Extract from the 1285 letter from Arghun to Honorius IV, Vatican[10]

This embassy also seems to have visited England and returned by way of Scandinavia: the Icelandic annal of Gottskalk notes:

"1286. [...]Komv Tartarar j Noreg og Hugi Nuncius og Fiportungar med herre Alfi"[11] ("Tartars came to Norway with Hugo Nuncius (the papal tithe collector Uguccio of Castillione) and men from the Five Ports with Lord Alv (english mercenaries in the pay of a norwegian noble)".

The diplomats visited the court of King Eric II Magnusson of Norway that year[12].

Second mission, to Kings Philip and Edward (1287)

Apparently left without an answer, Arghun sent another embassy to European rulers in 1287, headed by the Nestorian Rabban Bar Sauma, with the objective of contracting a military alliance to fight the Muslims in the Middle East, and take the city of Jerusalem.[7] The responses were positive but vague. Sauma returned in 1288 with positive letters from Pope Nicholas IV, Edward I of England, and Philip IV the Fair of France.[13] According to the medieval Syriac History of the two Nestorian Chinese monks, Bar Sawma of Khan Balik and Markos of Kawshang, as translated in Sir Wallis Budge's book The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China, Philip seemingly responded positively to the request of the embassy, gave him numerous presents, and sent one of his noblemen, Gobert de Helleville, to accompany Bar Sauma back to Mongol lands.

Gobert de Helleville departed on February 2, 1288, with two clerics Robert de Senlis and Guillaume de Bruyères, as well as arbaletier Audin de Bourges. They joined Bar Sauma in Rome, and accompanied him to Persia.[14]

In one of his letters, Nicholas IV also recognized the role of many Franks in the service of the Il-Khan, among them Ugi de Sienne, ilduci in the Guard of the Il-Khan, who would also bring a message to the West.[15]

Third mission (1289)

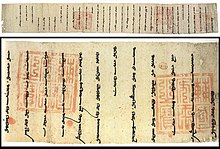

In 1289, Arghun sent a third mission to Europe, in the person of Buscarel of Gisolfe, a Genoese who had settled in Persia. The objective of the mission was to determine at what date concerted Christian and Mongol efforts could start. Arghun committed to march his troops as soon as the Crusaders had disembarked at Saint-Jean-d'Acre. Buscarel was in Rome between July 15 and September 30, 1289, and in Paris in November-December 1289. He remitted a letter from Arghun to Philippe le Bel, answering to Philippe's own letter and promises, offering the city of Jerusalem as a potential prize, and attempting to fix the date of the offensive from the winter of 1290 to spring of 1291:[16]

"Under the power of the eternal sky, the message of the great king, Arghun, to the king of France..., said: I have accepted the word that you forwarded by the messengers under Saymer Sagura (Bar Sauma), saying that if the warriors of Il Khaan invade Egypt you would support them. We would also lend our support by going there at the end of the Tiger year’s winter [1290], worshiping the sky, and settle in Damascus in the early spring [1291].

If you send your warriors as promised and conquer Egypt, worshiping the sky, then I shall give you Jerusalem. If any of our warriors arrive later than arranged, all will be futile and no one will benefit. If you care to please give me your impressions, and I would also be very willing to accept any samples of French opulence that you care to burden your messengers with.

I send this to you by Myckeril and say: All will be known by the power of the sky and the greatness of kings. This letter was scribed on the sixth of the early summer in the year of the Ox at Ho’ndlon."

Buscarello was also bearing a memorandum explaining that the Mongol ruler would prepare all necessary supplies for the Crusaders, as well as 30,000 horses.[19] Buscarel then went to England to bring Arghun's message to King Edward I. He arrived in London January 5, 1290. Edward, whose answer has been preserved, answered enthusiastically to the project but remained evasive and failed to make a clear commitment.[20]

Fourth mission (1290)

Arghun then sent a fourth mission to European courts in 1290, led by a certain Andrew Zagan, who was accompanied by Buscarel of Gisolfe and a Christian named Sahadin.[22] And also in 1290, the Pope sent the Franciscan John of Montecorvino to the Mongol court in Khanbaliq.[23]

Dispatch of a Genoese corps to Baghdad

However, all these attempts to mount a combined offensive failed. The only concrete example of military collaboration was when a maritime raiding force consisting in two war galleys was prepared in Baghdad by a corps of Genoese, in order to curtail the maritime trade of the Mamluks. A contingent of 800 Genoese carpenters and sailors was sent in 1290 to Baghdad, as well as a force of arbaletiers, but the enterprise apparently foundered when the Genoese government ultimatey disowned the project, and an internal fight erupted at the Persian Gulf port of Basra among the Geneose (between the Guelfe and the Gibelin families).[24][25]

On March 1291, the Mamluks conquered the last great Crusader outpost in the Siege of Acre

Death

Arghun died on March 7, 1291,[1] and was succeeded by his brother Gaykhatu.

The 13th century saw such a vogue of Mongol things in the West that many new-born children in Italy were named after Mongol rulers, including Arghun: names such as Can Grande ("Great Khan"), Alaone (Hulagu), Argone (Arghun) or Cassano (Ghazan) are recorded with a high frequency.[26]

Marco Polo

Arghun was the reason why Marco Polo was able to return to Venice after 23 years of absence. Having lost his favourite wife Bolgana (also Bulughan, or "Zibeline"), Arghun asked his grand-uncle and ally Kubilai Khan to send him a relative of his dead wife, named Kökötchin ("Blue, or Celestial, Dame"). Marco Polo was given the task of accompanying the princess through land and sea routes, navigating on a Mongolian ship through the Indian Ocean to Persia. Arghun died however in the meantime, and Kökötchin married Arghun's son Ghazan.

See also

- Timeline of Buddhism (see 1258 CE)

Notes

- ^ a b "He died on March 7, 1291." Steppes, p. 376

- ^ "Arghun had one of his sons baptized, Khordabandah, the future Oljaitu, and in the Pope's honour, went as far as giving him the name Nicholas", Histoire de l'Empire Mongol, Jean-Paul Roux, p.408

- ^ Jackson, p.176

- ^ Grousset, p.846

- ^ Mantran, Robert (Fossier, Robert, ed.) "A Turkish or Mongolian Islam" in The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 1250-1520, p. 298

- ^ Prawdin, p. 372. "Argun revived the idea of an alliance with the West, and envoys from the Ilkhans once more visited European courts. He promised the Christians the Holy Land, and declared that as soon as they had conquered Jerusalem he would have himself baptised there. The Pope sent the envoys on to Philip the Fair of France and to Edward I of England. But themission was fruitless. Western Europe was no longer interested in crusading adventures.

- ^ a b Runciman, p.398

- ^ Jackson, p.173

- ^ "The Crusades Through Arab Eyes" p. 254

- ^ Quote in "Histoires des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p700

- ^ Islandske annaler indtil 1578, Storm , g. Christiania 1888 Grousset, p337

- ^ Islandske annaler indtil 1578, Storm , g. Christiania 1888 Grousset, p70 and Arne Biskops saga chapter CIX, p136

- ^ Boyle, in Camb. Hist. Iran V, pp. 370-71; Budge, pp. 165-97. Source

- ^ "Histoires des Croisades III", Rene Grousset

- ^ Richard, "Histoire des Croisades", p.469

- ^ Runciman, p.401

- ^ Alternative translation of Arghun's letter

- ^ For another translation here

- ^ Jean Richard, p.468

- ^ "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset.

- ^ Vatican archives

- ^ Runciman, p.402

- ^ Foltz, p.130

- ^ "Only a contingent of 800 Genoese arrived, whom he (Arghun) employed in 1290 in building shipd at Baghdad, with a view to harassing Egyptian commerce at the southern approaches to the Red Sea", p.169, Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West

- ^ Jean Richard, p.468

- ^ Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West, p.315

References

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). The Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 0-8160-4671-9.

- Khan genealogy

- The Islamic World to 1600: The Mongol Invasions (The Il-Khanate)

- Rene Grousset, Histoires des Croisades

- Rene Grousset, Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, 1939

- Amin Maalouf, Crusades Through Arab Eyes

- Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, Vol. III