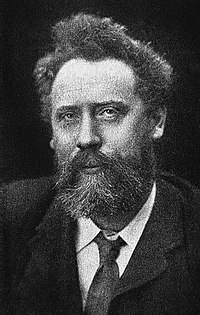

William Ernest Henley

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2008) |

William Ernest Henley (August 23, 1849 – July 11, 1903) was an English poet, critic and editor.

Henley was born at Gloucester and educated at the Crypt Grammar School. The school was a poor relation of the Cathedral School, and Henley indicated its shortcomings in his article, Pall Mall Magazine (Nov. 1900), on T. E. Brown, the poet who was headmaster there for a brief period. Brown's appointment was a stroke of luck for Henley, for whom it represented a first acquaintance with a man of genius: "He was singularly kind to me at a moment when I needed kindness even more than I needed encouragement". Brown did him the essential service of lending him books. Henley was no classical scholar, but his knowledge and love of literature were vital.

At the age of 12 Henley became a victim of tuberculosis of the bone. In spite of his affliction, in 1867 he successfully passed the Oxford local examination as a senior student. But a hospital was to be Henley's university. His diseased foot, treated by crude methods, had to be amputated directly below the knee. Worse yet, physicians announced that the only way to save his life was to amputate the other also. Henley fought this prognosis with all his spirit. The radical surgical methods pioneered by Joseph Lister saved Henley's foot and indeed his life. He was discharged from hospital in 1875 and was able to lead an active life for nearly 30 years. His friend, Robert Louis Stevenson, based his Treasure Island character, Long John Silver, on Henley.[citation needed]

His literary connections also led to his sickly young daughter Margaret being immortalised by J.M. Barrie in his children's classic "Peter Pan."[citation needed] Unable to speak clearly, the young Margaret referred to Barrie as her "Friendy Wendy", leading to the introduction of the name Wendy. Alas, Margaret never read the book as she died at the age of 6 and was buried at the country estate of her father's friend, Harry Cockayne Cust, in Cockayne Hatley, Bedfordshire.

After his recovery Henley earned his living in publishing. In 1889 he became editor of the Scots Observer, an Edinburgh journal on the lines of the old Saturday Review but inspired in every paragraph by Henley's vigorous and combative personality. It was transferred to London in 1891 as the National Observer and remained under Henley's editorship until 1893. Though, as Henley confessed, the paper had almost as many writers as readers, and its fame was mainly confined to the literary class, it was a lively and influential feature of the literary life of its time. Henley had the editor's great gift of discerning promise, and the "Men of the Scots Observer," as Henley affectionately and characteristically called his band of contributors, in most instances justified his insight. The paper found utterance for the growing imperialism of its day, and among other services to literature gave to the world Rudyard Kipling's Barrack-Room Ballads

Henley died at the age of 53 and was buried in the same churchyard as his daughter in Cockayne Hatley. His wife was later buried at the same site

Arguably his best-remembered work is the poem Invictus, written in 1875. It is said that this was written as a demonstration of his resilience following the amputation of his foot due to tubercular infection.

In 1890, Henley published Views and Reviews, a volume of notable criticisms, which he described as "less a book than a mosaic of scraps and shreds recovered from the shot rubbish of some fourteen years of journalism". The criticisms, covering a wide range of authors (all English or French save Heinrich Heine and Leo Tolstoy) were remarkable for their insight and gusto. In 1892, he published a second volume of poetry, named after the first poem, "The Song of the Sword" but re-christened "London Voluntaries" after another section in the second edition (1893). Stevenson wrote that he had not received the same thrill of poetry so intimate and so deep since George Meredith's "Joy of Earth" and "Love in the Valley". "I did not guess you were so great a magician. These are new tunes; this is an undertone of the true Apollo. These are not verse; they are poetry". In 1892, Henley published also three plays written with Stevenson — Beau Austin, Deacon Brodie and Admiral Guinea. In 1895, Henley's poem, "Macaire", was published in a volume with the other plays. Deacon Brodie was produced in Edinburgh in 1884 and later in London. Herbert Beerbohm Tree produced Beau Austin at the Haymarket on November 3, 1890.

Henley's poem, "Pro Rege Nostro", became popular during the First World War as a piece of patriotic verse. It contains the following refrain:

- What have I done for you, England, my England?

- What is there I would not do, England my own?

The poem and it sentiments have since been parodied by many people often unhappy with the jingoism they feel it expresses or the propagandistic use it is put to. "England, My England", a short story by D. H. Lawrence and also England, Their England the novel by A. G. Macdonell both use the phrase.

External links

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)