Nixtamalization

Nixtamalization is a process for the preparation of maize (corn) in which the grain is soaked and cooked in an alkaline solution, usually limewater, and hulled. Maize subjected to the nixtamalization process has several benefits over unprocessed grain for food preparation: it is more easily ground; its nutritional value is increased; flavor and aroma are improved; and mycotoxins are reduced. These benefits make nixtamalization a crucial preliminary step for futher processing of maize into food products, and the process is employed, using both traditional and industrial methods, in the production of tortillas, tamales, corn chips, and many other items.

Etymology

In the Aztec language Nahuatl, the word for the product of this procedure is nixtamalli or nextamalli (IPA: [niʃtaˈmalːi] or [neʃtaˈmalːi]), which in turn has yielded Mexican Spanish nixtamal ([nistaˈmal] or [niʃtaˈmal]). The Nahuatl word is a compound of nextli "ashes" and tamalli "unformed corn dough, tamal." The term nixtamalization (spelled with the "t") can also be used to describe the removal of the pericarp from any grain by an alkali process, including maize, sorghum, and others. When the unaltered Spanish spelling nixtamalizacion is used in written English, however, it almost exclusively refers to maize.

The labels on packages of commercially-sold tortillas prepared with nixtamalized maize usually list corn treated with lime as an ingredient in English, while the Spanish versions list maiz nixtamalizado.

History

Mesoamerica

The ancient process of nixtamalization was first developed in Mesoamerica, where maize was originally cultivated. There is no precise date when the technology was developed, but the earliest evidence of nixtamalization is found in Guatemala's southern coast, with equipment dating from 1200–1500 BC.

The ancient Aztec and Mayan civilizations developed nixtamalization using lime (calcium hydroxide, not the citrus fruit of the same name) and ash (potassium hydroxide) to creating alkaline solutions. The Chibcha people to the north of the ancient Inca also used calcium hydroxide (also known as "cal"), while the tribes of North America used natural-occurring sodium carbonate or ash.

The nixtamalization process was very important in the early Mesoamerican diet, as unprocessed maize is unbalanced in its essential amino acids and deficient in free niacin. A population depending on untreated maize as a staple food risks malnourishment, and is more likely to develop deficiency diseases such as pellagra and kwashiorkor. Maize cooked with lime provided essential amino acids and niacin in this diet.

The spread of maize cultivation in the Americas was accompanied by the adoption of the nixtamalization process, and traditional and contemporary regional cuisines (including Maya Cuisine, Aztec cuisine, and Mexican cuisine) included, and still include, foods based on nixtamalized maize.

The process has not substantially declined in usage in the Mesoamerican region, though there has been a decline in North America and many North American Native American tribes, such as the Huron, no longer use the process.[citation needed] In some Mesoamerican and North American regions food is still made from nixtamalized maize prepared by traditional techniques. The Hopi obtain the necessary alkali from ashes of various native plants and trees.[1][2] Some contemporary Maya use the ashes of burnt mussel shells.

In the United States, the nixtamalization process was not adopted by European settlers, though maize became a staple among the poor of the southern states. This led to endemic pellagra in poor populations throughout the southern US in the early twentieth century.[3]

Europe, Africa and India

Maize was introduced to Europe by Christopher Columbus in the 15th century, being grown in Spain as early as 1498. Due to its high yields, it quickly spread through Europe, and later to Africa and India. Portuguese colonists grew maize in the Congo as early as 1560, and maize became, and remains, a major food crop in parts of Africa.

Adoption of the nixtamalization process did not accompany the grain to Europe and beyond, perhaps because the Europeans already had more efficient milling processes for hulling grain mechanically. Without alkaline processing, maize is a much less beneficial foodstuff, and malnutrition struck many areas where it became a dominant food crop. In the nineteenth century, pellagra epidemics were recorded in France, Italy, and Egypt, and kwashiorkor hit parts of Africa where maize had become a dietary staple.

Health problems associated with maize-based diets have rarely, if ever, solved through adoption of nixtamalization, but rather through vitamin supplements, the fortification of grains, and economic improvement leading to a broader diet. Though pellagra has vanished from Europe and the United States, it remains a major public health problem in lower Egypt, parts of of South Africa, and southwestern India.

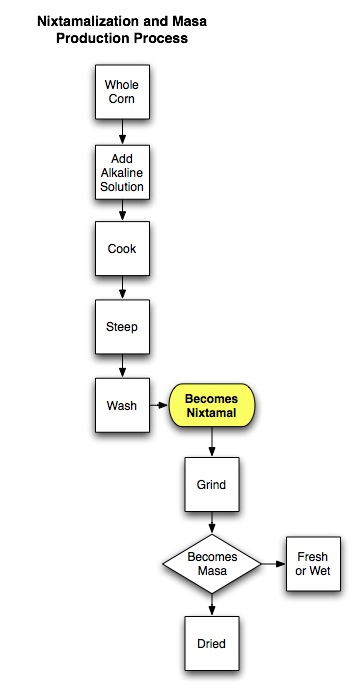

The Nixtamalization process

The first step in nixtamalization, kernels of dried maize are cooked in an alkaline solution at or near its boiling point. After cooking, the maize is steeped in the cooking liquid for a period. The length of time for which the maize is boiled and soaked varies according to local traditions and the type of food being prepared, with cooking times ranging from a few minutes to an hour, and soaking times from a few minutes to about a day.

During cooking and soaking, a number of chemical changes take place in the grains of maize. Because plant cell wall components, including hemicellulose and pectin, are highly soluble in alkaline solutions, the kernels soften and their pericarps (hulls) loosen. The grain hydrates and absorbs and calcium or potassium (depending on the alkali used) from the cooking solution. Starches swell and gelatinize, and some starches disperses into the liquid. Certain chemicals from the germ are released that allow the cooked grains to be ground more easily, yet make dough made from the grains less likely to tear and break down. Cooking changes the grain's protein matrix, which makes proteins and nutrients from the endosperm of the kernel more available to the human body.

After cooking, the alkaline liquid (known as nejayote), containing dissolved hull, starch, and other corn matter, is decanted and discarded. The kernels are washed thoroughly of remaining nejayote, which has an unpleasant flavor. The pericarp is then removed, leaving only the germ of the grain. This hulling is performed by hand, in traditional or very small-scale preparation, or mechanically, in larger scale or industrial production.

The prepared grain is called nixtamal. Nixtamal has many uses, contemporary and historic. Whole nixtamal may be used fresh or dried for later use. Whole nixtamal is used in the preparation of pozole and menudo, and other foods. Ground fresh nixtamal is made into dough and used to make tortillas, tamales, and arepas. Dried and ground, it is called masa harina or instant masa flour, and is reconstituted and used like masa.

The term hominy may refer to whole, coarsely ground, or finely ground nixtamal, or to a cooked porridge (also called samp) prepared from any of these.

Enzymatic Nixtamalization

An alternative process for use in industrial settings has been developed known as enzymatic nixtamalization which uses protease enzymes to accelerate the changes that occur in traditional nixtamalization. In this process, corn or corn meal is first partially hydrated in hot water, so that enzymes can penetrate the grain, then soaked briefly (for approximately 30 minutes) at 50°-60° C in an alkaline solution containing protease enzymes. A secondary enzymatic digestion may follow to further dissolve the pericarp. The resulting nixtamal is ground with little or no washing or hulling.

By pre-soaking the maize, minimizing the alkali used to adjust the pH of the alkaline solution, reducing the cooking temperature, accelerating processing, and reusing excess processing liquids, enzymatic nixtamalization can reduce the use of energy and water, lower nejayote waste production, decrease maize lost in processing, and shorten the production time (to approximately four hours) compared to traditional nixtamalization.[4]

Effects of enzymatic nixtamalization on flavor, aroma, nutritional value, and cost, compared to traditional methods, are not well-documented.

Nixtamalization and Health

The primary nutritional benefits of nixtamalization arise from the alkaline processing involved. These conditions convert corn's bound niacin to free niacin, making it available for absorption into the body. Alkalinity also reduces the amount of the protein zein available to the body, which, though this reduces the overall amount of protein, improves the balance among essential amino acids.

Secondary benefits can arise from the grain's absorption of minerals from the alkali used or from the vessels used in preparation. These effects can increase calcium (by 750%, with 85% available for absorption), iron, copper and zinc.

Lastly, nixtamalization significantly reduces (by 90-94%) mycotoxins produced by Fusarium verticillioides and Fusarium proliferatum, molds that commonly infect maize and the toxins of which are putative carcinogens.

Notes

- ^ Jennie Rose Joe and Robert S. Young (1993). Diabetes As a Disease of Civilization: The Impact of Culture Change on Indigenous People. Walter de Gruyter. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ^ Linda Murray Berzok (2005). American Indian Food. Greenwood Press. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ^ "Definition of Pellagra". MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ^ *Enzymatic process for nixtamalization of cereal grains, US Patent Issued on August 6 2002

References

- Coe, Sophie. America’s First Cuisines (1994). ISBN 0-292-71159-X

- Davidson, Alan. Oxford Companion to Food (1999), “Nixtamalization”, p. 534. ISBN 0-19-211579-0

- Kulp, Karen and Klaude J. Lorenz (editors). Handbook of Cereal Science and Technology (2000), p. 670. ISBN 0-8247-8358-1

- McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking, 2nd Edition (2004) p.477-478 ISBN 0-684-80001-2

- Wacher, Carmen “Nixtamalization, a Mesoamerican technology to process maize at small-scale with great potential for improving the nutritional quality of maize based foods” (2003)

- Food and Agricultural Organization, United Nations. Maize in Human Nutrition

- Smith, C. Wayne, Javier Betrán and E. C. A. Runge (editors). Corn: Origins, History and Technology (2004) p. 275 ISBN 0-471-41184-1