Fiduciary

- This page is about fiduciary in the legal sense. For optical field of view markers, see fiduciary marker.

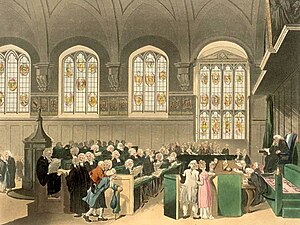

The fiduciary duty is a legal relationship between two or more parties (most commonly a "fiduciary" or "trustee" and a "principal" or "beneficiary") that in English common law is arguably the most important concept within the portion of the legal system known as equity. In the United Kingdom, the Judicature Acts merged the courts of Equity (historically based in England's Court of Chancery) with the courts of common law, and as a result the concept of fiduciary duty also became usable in common law courts.

A fiduciary duty is the highest standard of care imposed at either equity or law. A fiduciary is expected to be extremely loyal to the person to whom they owe the duty (the "principal"): they must not put their personal interests before the duty, and must not profit from their position as a fiduciary, unless the principal consents. The fiduciary relationship is highlighted by good faith, loyalty and trust, and the word itself originally comes from the Latin fides, meaning faith, and fiducia.

When a fiduciary duty is imposed, equity requires a stricter standard of behavior than the comparable tortious duty of care at common law. It is said the fiduciary has a duty not to be in a situation where personal interests and fiduciary duty conflict, a duty not to be in a situation where their fiduciary duty conflicts with another fiduciary duty, and a duty not to profit from their fiduciary position without express knowledge and consent. A fiduciary cannot have a conflict of interest. It has been said that fiduciaries must conduct themselves "at a level higher than that trodden by the crowd"[1] and that "[t]he distinguishing or overriding duty of a fiduciary is the obligation of undivided loyalty."[2]

Fiduciary duty in different jurisdictions

Different jurisdictions regard fiduciary duties in different lights. Canadian law, for example, has developed a more expansive view of fiduciary obligation, more so than American law, whilst Australian law and British law have developed more conservative approaches than either the USA or Canada. The law expressed here follows the general body of elementary fiduciary law found in most common law jurisdictions; for in-depth analysis of particular jurisdictional idiosyncrasies please consult primary authorities within the relevant jurisdiction.

Elements of the fiduciary duty

The person the duty is imposed on is called the fiduciary. A fiduciary will be liable to account if it is proved that the profit, benefit, or gain was acquired by one of three means:[3]

- In circumstances of conflict of duty and interest

- By taking advantage of the fiduciary position.

Therefore, it is said the fiduciary has a duty not to be in a situation where personal interests and fiduciary duty conflict, a duty not to be in a situation where their fiduciary duty conflicts with another fiduciary duty, and not to profit from their fiduciary position without express knowledge and consent. A fiduciary cannot have a conflict of interest.

Conflict of interest and duty

A fiduciary must not put themselves in a position where their interest and duty conflict.[4] In other words, they must always serve the principal's interests, subjugating their own preference for those of the principal. The fiduciary's state of mind is irrelevant; that is, it does not matter whether the fiduciary had any ill-intent or dishonesty in mind.

Although one area of growing concern is lawyers wanting to earn a good fee with the client's wishing to keep costs down. Australian High Court Chief Justice Murray Gleeson said; "Delay, like inflation, is sometimes convenient for those who are part of the system.", and " A basic problem of access to civil justice is the remorseless mercantilisation of legal practice." He added that time-based costing was part of the problem. "

Conflict of duty and duty

A fiduciary's duty must not conflict with another fiduciary duty.[5] Conflicts between one fiduciary duty and another fiduciary duty arise most often when a lawyer or an agent, such as a real estate agent, represent more than one client, and the interests of those clients conflict. This usually occurs when a lawyer attempts to represent both the plaintiff and the defendant in the same matter, for example. The rule comes from the logical conclusion that a fiduciary cannot make the principal's interests a top priority if he has two principals and their interests are diametrically opposed; he must balance the interests, which is not acceptable to equity. Therefore, the conflict of duty and duty rule is really an extension of the conflict of interest and duty rules.

No-profit rule

A fiduciary must not profit from the fiduciary position.[6] This includes any benefits or profits which, although unrelated to the fiduciary position, came about because of an opportunity that the fiduciary position afforded. It is unnecessary that the principal would have been unable to make the profit; if the fiduciary makes a profit, by virtue of their role as fiduciary for the principal, then the fiduciary must report the profit to the principal. If the principal consents then the fiduciary may keep the benefit. If this requirement is not met then the property is deemed by the court to be held by the fiduciary on constructive trust for the principal.

Secret commissions, or bribes, also come under the no profit rule. The bribe shall be held in constructive trust for the principal. The person who made the bribe cannot recover it, since they have committed a crime. Similarly, the fiduciary, who received the bribe, has committed a crime. Fiduciary duties are an aspect of equity and, in accordance with the equitable principles, or maxims, equity serves those with clean hands. Therefore, the bribe is held on constructive trust for the principal, the only innocent party.

Bribes were initially considered not to be held on constructive trust, but were considered to be held as a debit by the fiduciary to the principal.[7] This approach has been overruled; the bribe is now classified as a constructive trust.[8] The change is due to pragmatic flaws, especially in regard to a bankrupt fiduciary. If a fiduciary takes a bribe and that bribe is considered a debt then if the fiduciary goes bankrupt the debt will be left in his pool of assets to be paid to creditors and the principal may miss out on recovery because other creditors were more secured. If the bribe is treated as a constructive trust then it will remain in the possession of the fiduciary, despite bankruptcy, until such time as the principal recovers it.

Fiduciary relationships

The most common circumstance where a fiduciary duty will arise is between a trustee and a beneficiary. A trustee is the legal, i.e., common law owner of all the trust's property. The beneficiary, at law, has no legal title to the trust; however, the trustee is bound by equity to suppress his own interests and serve only the beneficiary. In this way, the beneficiary obtains the use of property without being its technical owner.

Relationships which routinely attract a fiduciary duty are as follows:

- Trustee/beneficiary: Keech v Sandford[9]

- Director/company: Woolworths Ltd v Kelly[10]

- Liquidator/company: Re Pantmaenog[11]

- Lawyer/client: Sims v Craig Bell & Bond[12]

- Partner/partner: Fraser Edmiston Pty Ltd v AGT (Qld) Pty Ltd;[13] Chan v Zacharia[14]

- Agent/principal: McKenzie v McDonald[15]

- Stockbroker/client: Hodgkinson v Simms[16]

- Senior employee/company: Green & Clara Pty Ltd v Bestobell Industries Pty Ltd[17]

- Doctor/Patient (in Canada[18]): McInerney v. MacDonald[19]

- Parent/Child: Paramasivam v Flynn [20]

- Teacher/Student: Glover v Porter-Gaud [21]

Possibly fiduciary relationships

Joint ventures, as opposed to business partnerships, are not presumed to carry a fiduciary duty; however, this is a matter of degree.[22] If a joint venture is conducted at commercial arm's length and both parties are on an equal footing then the courts will be reluctant to find a fiduciary duty, but if the joint venture is carried out more in the manner of a partnership then fiduciary relationships can and often will arise. Arklow vs. MacLean Privy Council 1999

Husbands and wives are not presumed to be in a fiduciary relationship; however, this may be easily established. Similarly, ordinary commercial transactions in themselves are not presumed to but can give rise to fiduciary duties, should the appropriate circumstances arise. These are usually circumstances where the contract specifies a degree of trust and loyalty or it can be inferred by the court.[23]

A protector of a trust may owe fiduciary duties to the beneficiaries, although there is no case law establishing this to be the case.[24]

Example: band members

For example, two members of a band currently under contract with one another (or with some other tangible, existing relationship that creates a legal duty), X and Y, record songs together. Let us imagine it is a serious, successful band and that a court would declare that the two members are equal partners in a business. One day, X takes a bunch of demos made cooperatively by the duo to a recording label, where an executive expresses interest. X pretends it is all his work and receives an exclusive contract and $50,000. Y is unaware of the encounter until reading it in the paper the next week.

This situation represents a conflict of interest and duty. Both X and Y hold fiduciary duties to each other, which means they must subdue their own interests in favour of the duo's collective interest. By signing an individual contract and taking all the money, X has put personal interest above the fiduciary duty. Therefore, a court will find that X has breached his fiduciary duty. The judicial remedy here will be that X holds both the contract and the money in a constructive trust for the duo. Note, X will not be punished or totally denied of the benefit; both X and Y will receive a half share in the contract and the money.

Breaches of duty and remedies

Where a principal can establish both a fiduciary duty and a breach of that duty, through violation of the above rules, the court will find that the benefit gained by the fiduciary should be returned to the principal because it would be unconscionable to allow the fiduciary to retain the benefit by employing his strict common law legal rights. This will be the case, unless the fiduciary can show there was full disclosure of the conflict of interest or profit and that the principal fully accepted and freely consented to the fiduciary's course of action.

Remedies will differ according to the type of damage or benefit. They are usually distinguished between proprietary remedies, dealing with property, and personal remedies, dealing with pecuniary (monetary) compensation.

Constructive trusts

Where the unconscionable gain by the fiduciary is in an easily identifiable form, such as the recording contract discussed above, the usual remedy will be the already discussed constructive trust.[25]

Constructive trusts pop up in many aspects of equity, not just in a remedial sense,[26] but, in this sense, what is meant by a constructive trust is that the court has created and imposed a duty on the fiduciary to hold the money in safekeeping until it can be rightfully transferred to the principal.

Account of profits

An account of profits is another potential remedy.[27] It is usually used where the breach of duty was ongoing or when the gain is hard to identify. The idea of an account of profits is that the fiduciary profited unconscionably by virtue of the fiduciary position, so any profit made should be transferred to the principal. It may sound like a constructive trust at first, but it is not.

An account for profits is the appropriate remedy when, for example, a senior employee has taken advantage of his fiduciary position by conducting his own company on the side and has run up quite a lot of profits over a period of time, profits which he wouldn't have been able to make without his fiduciary position in the original company. The calculation of profits in this sense can be extremely difficult, because profit due to fiduciary position must be separated from profit due to the fiduciary's own effort and ingenuity.

Compensatory damages

Compensatory damages are also available.[28] Accounts of profits can be hard remedies to establish, therefore, a plaintiff will often seek compensation (damages) instead. Courts of equity initially had no power to award compensatory damages, which traditionally were a remedy at common law, but legislation and case law has changed the situation so compensatory damages may now be awarded for a purely equitable action.

References

- ^ Meinhard v. Salmon (1928) 164 NE 545 at 546

- ^ ASIC v. Citigroup [2007] 62 ACSR 427 at 289

- ^ Keech v Sanford [1558-1774] All ER Rep 230

- ^ (1991) 22 NSWLR 189

- ^ [1991] 3 NZLR 535

- ^ [1988] 2 Qd R 1

- ^ Kak Loui Chan v. John Zacharia (1984) 58 ALJR 353

- ^ [1927] VLR 134

- ^ [1994] 3 SCR 377

- ^ [1982] WAR 1

- ^ (1996) 186 CLR 71

- ^ [1998] 1711 FCA

- ^ United Dominions Corporation v Brian Pty Ltd (1985) 59 ALJR 676

- ^ United States Surgical Corporation v Hospital Products International Pty Ltd (1984) 58 ALJR 587

- ^ Note 6

- ^ Phipps v Boardman [1967] 2 AC 46

- ^ Stewart v Layton (1992) 111 ALR 687

- ^ Note that Canada is the only common law jurisdiction in the world that recognises the doctor/patient relationship as a fiduciary one.

- ^ McInerney v. MacDonald [1992] 2 SCR 138, (1992) 126 N.B.R. (2d) 271, (1992) 126 N.B.R. (2e) 271, (1992) 93 D.L.R. (4th) 415, 1992 CanLII 57 (S.C.C.)

- ^ Lister v Stubbs (1890) 45 Ch D 1

- ^ Attorney General (Hong Kong) v Reid [1993] 3 WLR 1143

- ^ Giumelli v Giumelli (1999) 73 ALJR 54

- ^ Muchinski v Dodds (1986) 60 ALJR 52

- ^ Dart Industries Inc v Decor Corporation Pty Ltd (1993) 179 CLR 101

- ^ Nocton v Lord Ashburton [1914] AC 932

- ^ Re Pantmaenog [2004] 1 AC 158

- ^ Glover v Porter-Gaud (2000) 98-CP-10-613

- ^ Although under the laws of Idaho it seems to be assumed that a protector is a fiduciary.[29]

Template:Murray Gleeson(October 2007) Speaking to the Judicial Conference of Australia's annual meeting in Sydney