Rights of Man

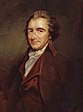

Title page from the first edition | |

| Author | Thomas Paine |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

Publication date | 1791 |

| Publication place | Britain |

Rights of Man was written by Thomas Paine in 1791 as a reply to Reflections on the Revolution in France by Edmund Burke. It has been interpreted as a work defending the French Revolution, but it is also a seminal work embodying the ideas of liberty and human equality.[1]

Conception

Many of the ideas in Rights of Man are derived from the concepts of the Age of Enlightenment. John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government particularly influenced Paine who ascribes the origins of rights to nature. Paine emphasizes that rights cannot be granted by any charter because this would legally imply they can also be revoked and under such circumstances they would be reduced to privileges.

Paine writes, “It is a perversion of terms to say that a charter gives rights. It operates by a contrary effect - that of taking rights away. Rights are inherently in all the inhabitants; but charters, by annulling those rights, in the majority, leave the right, by exclusion, in the hands of a few. ... They...consequently are instruments of injustice. ”

“The fact therefore must be that the individuals themselves, each in his own personal and sovereign right, entered into a compact with each other to produce a government: and this is the only mode in which governments have a right to arise, and the only principle on which they have a right to exist.”

According to Paine, the sole purpose of the government is to protect the irrefutable rights inherent to every human being. Thus all institutions which do not benefit a nation are illegitimate, including the monarchy (and the nobility) and the military establishment.

The Rights of Man and reforms in the English Government

Paine ends the book by proposing to reform the English government. His first demand is a written English constitution created by a national assembly but modeled along the lines of the American one. Further he suggests elimination of all aristocratic titles, seeking a democracy which would exclude such unfair practices as primogeniture which inevitably leads to what he calls “despotism of the family”. He proposes a budget which calls for an alliance with France and America and the eventual doing away with war and military expenses. He also suggests economic reforms in the shape of tax-cuts for the poor and subsidies for their education. Finally he proposed a sort of “progressive taxation”, declaring that more wealthy estates should be taxed more heavily to prevent the emergence of the hereditary aristocracy.

Aristocracy

The Rights of Man primarily opposes Burke's projected notion of hereditary government. Burke's conservative notion of power centers in the idea that a dictatorial government of the people is necessitated by the corrupt nature of human beings. A staunch supporter of the aristocracy as well as a disbeliever of true democracy, Burke suggests that true social stability would arise if the poverty-ridden majority were to be governed by an exclusive minority of wealthy noblemen. According to Burke, the lawful inheritance of wealth or religious power ensured the propriety of power being the exclusive domain of the elite. Paine's arguments denounce Burke’s assertion of hereditary wisdom and judge his declarations as most offensive.

Not withstanding the nonsense, for it deserves no better name, that Mr. Burke has asserted about hereditary rights, and hereditary succession, and that a Nation has not a right to form a Government of itself; it happened to fall in his way to give some account of what Government is. 'Government,' says he, 'is a contrivance of human wisdom.'. . . Admitting that government is a contrivance of human wisdom, it must necessarily follow, that hereditary succession, and hereditary rights (as they are called), can make no part of it, because it is impossible to make wisdom hereditary.

Heredity

In the Reflections on the French Revolution, Burke traces the legitimacy of an aristocratic government to the Parliamentary resolution declaring William and Mary of Orange and their heirs to be the true rulers of England. Paine asserts that the institution of Monarchy should not be traced back to 1688 but to 1066 when William of Normandy forcibly imposed his rule on England. Paine declares Burke’s argument null and void since the entary

Paine’s influence was perceptible in both the great revolutions of the eighteenth century. The Rights of Man is dedicated to U.S. General George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette acknowledging the importance of the American and the French Revolution in formulating the principles of modern democratic governance. The Declaration of the Rights of Man can be approached from his most telling points: 1. Men are born, and always continue, free and equal in respect of their rights. Civil distinctions, therefore, can be founded only on public utility. 2. The end of all political associations is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptibly rights of man; and these rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance of oppression. 3. The nation is essentially the source of all sovereignty; neither can any individual, nor any body of men, be entitled to any authority which is not expressly derived from it. These three points are similar to the "self-evident truths" expressed in the United States Declaration of Independence.

Impact

When the French Revolution broke out, Paine went to France where, despite his ignorance of the French language, he was promptly elected to the National Convention. His absence from England at this time was fortuitous because the publication of The Rights of Man caused such a furor in the country that Paine was put on trial in absentia and convicted for seditious libel against the crown.

Thomas Paine was not the only advocate of the rights of man or author of a work with that title. The working class radical Thomas Spence has some claims to be amongst the first in England to use the phrase. His 1775 lecture, usually titled 'The Rights of Man', along with his later 'The Rights of Infants', offer what some have claimed to be a proto-communist alternative to Paine.[2]

Controversies

Though Paine and his works are generally seen as thoroughly egalitarian, democratic and representing human rights and justice, there are at least a few instances of Paine exhibiting traits opposing these ideals. For example, when examining why the "French Constitution has resolved against having" a hereditary-based legislative branch, Paine says the Jews prove "the human species has a tendency to degenerate, in any small number of persons, when separated from the general stock of society, and inter-marrying constantly with each other." On page 269 of the recent Signet Edition, he likens the immorality of monarchy with the sins of the Jews.

References

See also

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen - a fundamental document of the French Revolution, adopted in 1789