Atomic bombings of Japan as a form of state terrorism

It has been suggested that this article be merged into Allegations of state terrorism by the United States and Talk:Allegations_of_state_terrorism_by_the_United_States#Ending_the_war_over_the_war_over_Japan. (Discuss) Proposed since May 2008. |

It has been suggested that this article be merged into Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Talk:Allegations_of_state_terrorism_by_the_United_States#Ending_the_war_over_the_war_over_Japan. (Discuss) Proposed since May 2008. |

For scholars and historians, the primary ethics debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,[1] relate to whether the use of nuclear weapons were justified. A small minority argue that it was a form of state terrorism. Such an interpretation centers around an definition of terrorism as "the targeting of civilians to achieve a political goal";[2] and applying the definition to wartime acts by belligerent nations.[3]

Scholars have also argued that the bombings weakened moral taboos against attacks on civilians, leading to such attacks becoming a standard tactic in subsequent U.S. military actions, [4] though the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki remain the only time a state has used nuclear weapons against concentrated civilian populated areas.[5][6]

Views and opinions

Debate: Morality and necessity

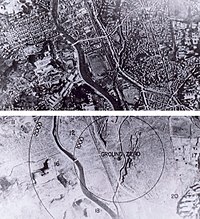

The debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is a subject of contention concerning the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which took place on August 6 and 9, 1945 and marked the end of World War II. The debate amongst scholars, popular media, and cultures tends to focus on the ethics and necessity of the bombings. The role of the bombings in Japan's surrender and the United States' justification for them has been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades. J. Samuel Walker notes in an April 2005 overview of recent historiography on the issue, that "The fundamental issue that has divided scholars over a period of nearly four decades is whether the use of the bomb was necessary to achieve victory in the war in the Pacific on terms satisfactory to the United States."[7]

Viewed as state terrorism

The use of the term "terrorism" to describe is sometimes used as a polemic device to extract moral equivalence between acts committed against the United States or its people and acts carried out by or on behalf of the United States. For example, the controversial Reverend Jeremiah Wright, during a sermon discussing the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, was quoted as saying

We bombed Hiroshima, we bombed Nagasaki, and we nuked far more than the thousands in New York and The Pentagon, and we never batted an eye... and now we are indignant, because the stuff we have done overseas is now brought back into our own front yards. America's chickens are coming home to roost.

The equally controversial Ward Churchill also brought up imagery of the atomic bombings of Japan in his polemic writings on the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.[8]

The interpretation by scholars of the atomic attacks as incidents of state terrorism relies upon the targeting of civilians to achieve a political goal. According to the meeting of the Secret Target Committee in Los Alamos on 10 and 11 May 1945, they targeted the large population centers of Kyoto or Hiroshima for a "psychological effect" and as a means to make atomic bomb's "initial use sufficiently spectacular for the importance of the weapon to be internationally recognized."[9][2] As such, Frances V. Harbour suggests the goal was to create "civilian terror" for political ends both in and beyond Japan.[2]

Historian Howard Zinn writes: "if 'terrorism' has a useful meaning (and I believe it does, because it marks off an act as intolerable, since it involves the indiscriminate use of violence against human beings for some political purpose), then it applies exactly to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki."[10] Zinn cites the sociologist Kai Erikson who states that:

The attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not 'combat' in any of the ways that word is normally used. Nor were they primarily attempts to destroy military targets, for the two cities had been chosen not despite but because they had a high density of civilian housing. Whether the intended audience was Russian or Japanese or a combination of both, then the attacks were to be a show, a display, a demonstration. The question is: What kind of mood does a fundamentally decent people have to be in, what kind of moral arrangements must it make, before it is willing to annihilate as many as a quarter of a million human beings for the sake of making a point?[10]

Michael Walzer writes of it as an example of "...war terrorism: the effort to kill civilians in such large numbers that their government is forced to surrender. Hiroshima seems to me the classic case."[11]

Professor Tony Coady writes in Terrorism and Justice: Moral Argument in a Threatened World that "Several of the contributors consider the issue of state terrorism and there is a general agreement that states not only can sponsor terrorism by non state groups but that states can, and do, directly engage in terrorism." Coady instances the terror bombings of World War II, including Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as acts of terrorism.[12]

Richard A. Falk, professor Emeritus of International Law and Practice at Princeton University has written in detail about Hiroshima and Nagasaki as instances of state terrorism. He writes "The graveyards of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the number-one exhibits of state terrorism... Consider the hypocrisy of an Administration that portrays Qaddafi as barbaric while preparing to inflict terrorism on a far grander scale.... Any counter terrorism policy worth the name must include a convincing indictment of the First World variety."[13][14]. He writes elsewhere that:[15]

Undoubtedly the most extreme and permanently traumatizing instance of state terrorism, perhaps in the history of warfare, involved the use of atomic bombs against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in military settings in which the explicit function of the attacks was to terrorize the population through mass slaughter and to confront its leaders with the prospect of national annihilation....the public justification for the attacks given by the U.S. government then and now was mainly to save lives that might otherwise might have been lost in a military campaign to conquer and occupy the Japanese home islands which was alleged as necessary to attain the war time goal of unconditional surrender.... But even accepting the rationale for the atomic attacks at face value, which means discounting both the geopolitical motivations and the pressures to show that the immense investment of the Manhattan Project had struck pay dirt, and disregarding the Japanese efforts to arrange their surrender prior to the attacks, the idea that massive death can be deliberately inflicted on a helpless civilian population as a tactic of war certainly qualifies as state terror of unprecedented magnitude, particularly as the United States stood on the edge of victory, which might well have been consummated by diplomacy. As Michael Walzer puts it, the United States owed the Japanese people 'an experiment in negotiation,' but even if such an initiative had failed there was no foundation in law or morality for atomic attacks on civilian targets.

The President of Venezuela, Hugo Chavez, while paying tribute to the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, referred to the bombings as "the greatest act of terrorism in recorded history."[16]

Historian Robert Newman — a supporter of the bombings — has responded to these criticisms by arguing that the practice of terrorism is sometimes justified.[17]

Viewed as primarily wartime acts

Burleigh Taylor Wilkins states in Terrorism and Collective Responsibility that "any definition which allowed the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to count as instances of terrorism would be too broad." He goes on to explain "The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, while obviously intended by the American government to alter the policies of the Japanese government, seem for all the terror they involved, more an act of war than of terrorism."[3]

It has also been argued, under the view that Japan was involved in a total war, that therefore there was no difference between civilians and soldiers.[18] The targets, while they may not primarily have been chosen for this reason, still had a certain strategic military value. Hiroshima was used as headquarters of the Fifth Division and the 2nd General Army, which commanded the defense of southern Japan with 40,000 military personal in the city, and was a communication center, a storage point with military factories.[19][20][21] Nagasaki was of wartime importance because of its wide-ranging industrial activity, including the production of ordnance, ships, military equipment, and other war materials.[22]

Viewed as diplomacy or state terrorism not considered

Critical scholarship has focused on the argument that the use of atomic weapons was "primarily for diplomatic purposes rather than for military requirements ... to impress and intimidate the Soviet Union in the emerging Cold War."[23] Certain scholars who oppose the decision to use of the atom bomb, while they state it was unnecessary and immoral, do not claim it was state terrorism per se. Walker's 2005 overview of recent historiography did not discuss the issue of state terrorism.[24]

Forward effects

Political science professor Michael Stohl and peace studies researcher George A. Lopez, in their book Terrible beyond Endurance? The Foreign Policy of State Terrorism, discuss the argument that the institutionalized form of terrorism carried out by states have occurred as a result of changes that took place following World War II, and in particular the two bombings. In their analysis state terrorism as a form of foreign policy was shaped by the presence and use of weapons of mass destruction, and that the legitimizing of such violent behavior led to an increasingly accepted form of state behavior. They consider both Germany’s bombing of London (q.v. The Blitz) and the U.S. atomic destruction of Hiroshima.

Scholars treating the subject have discussed the bombings within a wider context of the weakening of the moral taboos that were in place prior to WWII, which prohibited mass attacks against civilians during wartime. Mark Selden, professor of sociology and history at Binghamton University and author of War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century, writes, "This deployment of air power against civilians would become the centerpiece of all subsequent U.S. wars, a practice in direct contravention of the Geneva principles, and cumulatively the single most important example of the use of terror in twentieth century warfare."[25] Falk, Selden, and Prof. Douglas Lackey, each of whom relate the Japan bombings to what they believe was a similar pattern of state terrorism in following wars, particularly the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Professor Selden writes: “Over the next half century, the United States would destroy with impunity cities and rural populations throughout Asia, beginning in Japan and continuing in North Korea, Indochina, Iraq and Afghanistan, to mention only the most heavily bombed nations...if nuclear weapons defined important elements of the global balance of terror centered on U.S.-Soviet conflict, "conventional" bomb attacks defined the trajectory of the subsequent half century of warfare."[4]

See also

- Allegations of state terrorism by the United States

- Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

References

- ^ See: Walker, J. Samuel (2005). "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: A Search for Middle Ground". Diplomatic History. 29 (2): 334.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Harbour, Frances Vryling (=1999). Thinking About International Ethics: Moral Theory And Cases From American Foreign Policy. pp. 133f. ISBN 0813328470.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Wilkins, Burleigh Taylor. Terrorism and Collective Responsibility. Routledge. p. 11. ISBN 041504152X.

- ^ a b Selden, War and State Terrorism.

- ^

Frey, Robert S. (2004). The Genocidal Temptation: Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Rwanda and Beyond. University Press of America. ISBN 0761827439. Reviewed at:

Rice, Sarah (2005). "The Genocidal Temptation: Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Rwanda and Beyond (Review)". Harvard Human Rights Journal. Vol. 18.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^

Dower, John (1995). "The Bombed: Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japanese Memory". Diplomatic History. Vol. 19 (no. 2).

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Walker, J. Samuel (2005-April). "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: A Search for Middle Ground". Diplomatic History. 29 (2): 334.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Churchill, Ward (2005). "The Ghosts of 9-1-1: Reflections on History, Justice and Roosting Chickens". Alternative Press Review. 9 (1): 45–56.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) (a reprint of the first part of the book) - ^ Record Group 77, Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, Manhattan Engineer District, TS Manhattan Project File (1945-05-26). "Minutes of the second meeting of the Target Committee". Retrieved 2005-08-06.

It was agreed that psychological factors in the target selection were of great importance. Two aspects of this are (1) obtaining the greatest psychological effect against Japan and (2) making the initial use sufficiently spectacular for the importance of the weapon to be internationally recognized when publicity on it is released. B. In this respect Kyoto has the advantage of the people being more highly intelligent and hence better able to appreciate the significance of the weapon. Hiroshima has the advantage of being such a size and with possible focusing from nearby mountains that a large fraction of the city may be destroyed. The Emperor's palace in Tokyo has a greater fame than any other target but is of least strategic value.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 333 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Hiroshima; Breaking the Silence". Retrieved 2008-01-30.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ Walzer, Michael (2002). "Five Questions About Terrorism" (PDF). 49 (1). Foundation for the Study of Independent Social Ideas, Inc. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) - ^ Coady, Tony (2004). Terrorism and Justice: Moral Argument in a Threatened World. Melbourne University Publishing. pp. XV. ISBN 0522850499.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Falk, Richard (1988). Revolutionaries and Functionaries: The Dual Face of Terrorism. Dutton.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Falk, Richard (January 28, 2004). "Gandhi, Nonviolence and the Struggle Against War". The Transnational Foundation for Peace and Future Research. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Falk, Richard. "State Terror versus Humanitarian Law",in Selden,, Mark, editor (November 28, 2003). War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.. ISBN 978-0742523913. ,45

- ^ Campanioni, Maria Salomé (2005-08-08). "Chavez Calls Dropping of A-Bomb, 'Greatest Act of Terrorism in Recorded History'". watchingamerica.com. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Newman, Robert (2004). Enola Gay and the Court of History (Frontiers in Political Communication). Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 0-8204-7457-6.

- ^ "The Avalon Project : The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki". Retrieved 2005-08-06.

- ^ "Hiroshima Before the Bombing". Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Hanson, Victor Davis (August 05, 2005). ""60 Years Later: Considering Hiroshima"". National Review. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Hoffmann, Hubertus. "Hiroshima: Hubertus Hoffmann meets the only U.S. Officer on both A-Missions and one of his Victims".

- ^ "The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima".

- ^ Walker, J. Samuel (2005-April). "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision: A Search for Middle Ground". Diplomatic History. 29 (2): 312.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Walker, "Recent Literature on Truman's Atomic Bomb Decision," passim.

- ^ Selden, Mark (2002-09-09). "Terrorism Before and After 9-11". Znet. Retrieved 2008-01-30.