Bone Wars

The Bone Wars is the name given to a period of intense fossil speculation and discovery in the United States during the Gilded Age of American history, fueled by a heated rivalry between paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope. Both scientists used underhanded methods to out-compete the other in the field, sometimes resorting to bribery and destruction of bones. Cope and Marsh also attacked each other in scientific publications and attempted to ruin the other's credibility.

Their rivalry sparked in part by dinosaur finds in New Jersey and allegations of theft and bribery, Cope and Marsh's pursuit of bones led them west to rich bone beds in Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming. Cope and Marsh used their wealth and influence to hire dinosaur hunters to send them fossils. The digging lasted from 1877 to 1892, by which time both men had exhausted their funds.

Both Cope and Marsh were financially and socially ruined by their efforts to disgrace each other, but their contributions to science and the field of paleontology were massive; both Marsh and Cope had tons of unopened boxes of fossils between them left over after their deaths. The bitter feud between the two men led to over 142 new species of dinosaurs being discovered, and 1,818 species or genera of fossil vertebrates described between them. Not only did the products of the Bone Wars result in an increase in knowledge of ancient life, but the public's interest in dinosaurs was sparked and led to continued fossil excavation in North America in the decades to come.

History

Background

At one time, Cope and Marsh were friends. The two had met in Berlin, Germany in 1864, and spent several days together. At one point, their friendship was so strong that they even named species after each other.[1] Over time, however, their relations soured, due in part to their temperaments. Cope was known to be pugnacious and possessed a quick temper; Marsh was slower and more methodical, and despite his powerful friends was very introverted. Both were quarrelsome and distrustful.[2]

On one occasion, the two scientists had gone on a fossil-collecting expedition to Cope's marl pits in New Jersey, where William Parker Foulke had discovered the holotype specimen of Hadrosaurus foulkii, described by Joseph Leidy.[1] Though the two parted amicably, Marsh secretly bribed the pit operators to divert the fossils they were discovering to him, instead of Cope.[1] The two began attacking each other in papers and publications, and their personal relations soured.[3] Marsh humiliated Cope by pointing out his reconstruction of Elasmosaurus was flawed, with the head placed where the tail should have been. Cope, in turn, began collecting in what Marsh considered his private bone-hunting turf in Kansas and in Wyoming.[3][4] Any pretense of cordiality between the two ended in 1872, and open hostility ensued.[5]

Como Bluff and the West

In the 1870s, both men's attention was attracted to the American West by word of fossils. In 1877, Marsh received a letter from Arthur Lakes, a schoolteacher in Golden, Colorado. Lakes reported that he had been hiking in the mountains near the town of Morrison when he and H. C. Beckwith, his friend, had discovered massive bones embedded in the rock. Lakes wrote in his letter that the bones were "apparently a vertebra and a humerus bone of some gigantic saurian."[6] While awaiting Marsh's reply, Lakes dug up more "colossal" bones and sent them to New Haven. As Marsh was slow to respond, Lakes also sent a shipment of bones to Cope.

When Marsh responded to Lakes, he paid the prospector $100, urging him to keep the finds a secret. Learning that Lakes had corresponded with Cope, Marsh sent his field collector Benjamin Mudge to Morrison to secure Lake's services. At the same time Marsh published a description of Lake's discoveries in the American Journal of Science on July 1, and before Cope could publish his own interpretation of the finds, Lakes wrote him that the bones should be shipped to Marsh, a severe insult to Cope.[7]

A second letter arrived from the West, this time addressed to Cope. O.W. Lucas was a naturalist who had been collecting plants near Cañon City, Colorado, when he have come upon an assortment of fossil bones. After receiving more samples from Lucas, Cope concluded the dinosaurs had been large herbivores, larger than any other specimen described at the time.[7] Marsh heard of Lucas' finds and instructed Mudge and his former student Samuel Wendell Williston to set up his own quarry near Cañon. Unfortunately for Marsh, Williston reported to Marsh that Lucas was finding the best bones and that he had refused to quit Cope and work for Marsh.[8]

At the same time, the Transcontinental Railroad was being built through a remote area of Wyoming. Marsh received a letter from two men identifying themselves as Harlow and Edwards (their real names were Carlin and Reed), workers on the Union Pacific Railroad. The two men claimed they had found large amounts of fossils in Como Bluff, and warned that there were others in the area "looking for such things",[9] which Marsh took to mean Cope. Marsh sent Williston to the site, who sent a message to Cope that both the large quantities of bones, and the reports of Cope's men snooping around in the area were true.[10] Without delay both Cope and Marsh sent their men to Como Bluff to begin digging.

Both Cope and Marsh were wealthy—Cope's father was a rich Philadelphia businessman, and while Marsh came from a modest background himself he received patronage from his uncle, George Peabody[11]— and they each used their personal wealth to fund expeditions each summer, then spent the winter publishing their discoveries. Small armies of fossil hunters in mule-drawn wagons or on trains were soon sending literal tons of fossils back East.[12] The digging lasted fifteen years, from 1877 to 1892.[13]

Cope and Marsh's discoveries were accompanied by sensational accusations of spying, stealing workers, stealing fossils, and bribery. The two men were so protective of their digging sites they would destroy smaller or damaged fossils to prevent them from falling into their rival's hands, or filled in their excavations with dirt and rock.[14] While the scientific community had long known of Marsh and Cope's rivalry, the public became aware of the shameful conduct of the two men on January 12, 1890, when the New York Herald published a story with the headline "Scientists Wage Bitter Warfare."[14] According to author Elizabeth Noble Shor, the scientific community was galvanized:

Most scientists of the day recoiled in horror—and read on with interest, to find that Cope's feud with Marsh had at last become front-page news. Those closest to the scientific fields under discussion, geology and vertebrate paleontology, certainly winced, particularly as they found themselves quoted, mentioned, or misspelled. The feud was not news to them, for it had lurked at their scientific meetings for two decades. Most of them had already taken sides.[15]

Personal disputes

While Cope and Marsh dueled for fossils in the American West, they also tried their best to ruin each others' professional credibility. Cope's error in reconstructing the sea reptile Elasmosaurus humiliated Cope, who tried to cover up his mistake by purchasing every copy he could find of the journal it was published in.[16] Marsh, who pointed out the error in the first place, made sure to publicize the story. Cope's own rapid and prodigious output of scientific papers meant that Marsh had no difficulty in finding occasional errors to lambast Cope with.[4] Marsh was by no means more infallible; he put the wrong skull on a skeleton of Apatosaurus and declared it a new genus, Brontosaurus.[17]

Cope over the years kept an elaborate journal of mistakes and misdeeds that both Marsh and John Wesley Powell, head of the U.S. Geological Survey (and Marsh's ally), had committed; the mistakes and errors of the men were put in writing and ensconced in the bottom drawer of Cope's desk.[18] Reporter William Hosea Ballou ran the first article on January 12, 1890, in what would become a series of newspaper debates between Marsh, Powell and Cope.[19]

Cope was by this time a teacher at the University of Pennsylvania; Marsh was a participant in the Geological Survey and the head of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, which Uncle Peabody had created at Marsh's behest years earlier.[20] In the newspaper articles, Cope attacked Marsh for plagiarism and financial mismanagement and attacked Powell for his geological classification errors and misspending of government allocated funds.[21] Marsh and Powell were each able to publish their own side of the story and in the end little changed between them. No congressional hearing was created to investigate the misallocation of funds by Powell and neither Cope nor Marsh was held responsible for any of their mistakes. Marsh was however quickly removed from his position as paleontologist for the government surveys, Cope's relations with the president of the University of Pennsylvania soured, and the entire funding for paleontology in the government surveys was pulled.[22]

Legacy

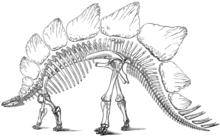

Judging by pure numbers, Marsh "won" the Bone Wars. Both scientists made finds of incredible scientific value, but while Marsh discovered a total of 80 new dinosaur species, Cope only discovered 56.[12][24] Among the species the two men discovered are the most well-known dinosaurs today, including species of Triceratops, Allosaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus, Camarasaurus and Coelophysis. Cope and Marsh's cumulative discoveries defined the then-nascent field of paleontology; before Cope and Marsh's discoveries, there were only nine named species of dinosaur in North America.[24] Furthermore, some of their ideas—such as Marsh's argument that birds are descended from dinosaurs—have been upheld; while others, including "Cope's law", which states that over time species tend to get larger, are viewed as having little to no scientific merit.[25] The Bone Wars also led to the discovery of the first complete skeletons, and the rise in popularity of dinosaurs with the public. As paleontologist Robert Bakker stated, "The dinosaurs that came from [Como Bluff] not only filled museums, they filled magazine articles, textbooks, they filled people's minds."[13]

Cope and Marsh's rivalry lasted until Cope's death in 1897, by which time both men had been financially ruined. Cope faced a series of financial setbacks, both from the lack of federal funding as well as failed business investments in silver mines;[4] Cope had to sell part of his collection and rent out one of his homes. Marsh in turn had to mortgage his home and ask Yale for a salary to live on.[4] Cope issued a final challenge at his death.[1] He had his skull donated to science so that his brain could be measured, hoping that his brain would be larger than that of his adversary; at the time, it was thought brain size was the true measure of intelligence. Marsh never rose to the challenge, but Cope's skull is still preserved at University of Pennsylvania[1] (though whether the skull is actually Cope's is disputed; the University stated that it believes the real skull was lost in the 1970s, though Robert Bakker states that hairline fractures on the skull and coroner's reports verify the skull's provenance.)[26]

The Bone Wars had a negative impact not only on the two scientists but their peers and the entire field. Their animosity and public behavior harmed the reputation of American paleontology in Europe for decades. Furthermore, the reported use of dynamite and sabotage by employees of both men destroyed or buried hundreds of potentially critical fossil remains. It will never be known how much their rivalry has damaged our understanding of life forms in the regions which they worked. Joseph Leidy abandoned his own more methodical excavations in the west, finding he could not keep up with Cope and Marsh's reckless search for bones.[27]

Recent excavation of several of Cope and Marsh's sites suggest that some of the damage propagated by the two paleontologists was less than what has been recorded. Using Lakes' field paintings, researchers from the Morrison Natural History Museum discovered that Lakes had not actually dynamited the most productive quarries in Colorado; rather, Lakes had just filled in the site. Museum director Matthew Mossbrucker theorized that Lakes propagated the lie "because he didn't want the competition up at the quarry—playing mind games with Cope's gang.[28]

Adaptations

Besides being the subject of historical and paleontological books, the Bone Wars has been the subject of a graphic novel, Bone Sharps, Cowboys, and Thunder Lizards, by Jim Ottaviani. Bone Sharps is a work of historical fiction, as Ottaviani introduces the character of Charles R. Knight to Cope for plot purposes, and other events have been restructured.[29] The Bone Wars was featured in more fantastical form, in the book Bone Wars by Brett Davis, which includes aliens also interested in the bones.[30]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Dodson.

- ^ Bryson, 92.

- ^ a b Preston, 61.

- ^ a b c d Penick.

- ^ Wilford, 87.

- ^ Wilford, 105.

- ^ a b Wilford, 106.

- ^ a b Wilford, 107.

- ^ Wilford, 108.

- ^ Preston, 62.

- ^ Bryson, 93.

- ^ a b Bates.

- ^ a b Bakker.

- ^ a b Preston, 63.

- ^ Shor.

- ^ Jaffe, 15.

- ^ Rajewski, 22.

- ^ Osborn, 585.

- ^ Osborn, 403.

- ^ Farlow, 709.

- ^ Osborn Osborn, 404.

- ^ Jaffe, 329.

- ^ Norell, 112.

- ^ a b Colbert, 93.

- ^ Trefil, 95.

- ^ Baalke.

- ^ Academy of Natural Sciences.

- ^ Rajewski, 21.

- ^ Mondor.

- ^ Waggoner.

References

- Baalke, Ron (1994-10-13). "Edward Cope's Skull". lepomis.psych.upenn.edu (Mailing list). Retrieved 2008-08-15.

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - Bates, Robin (series producer), Chesmar, Terri and Baniewicz, Rich (associate producers); Dodson, Peters, Bakker, Robert (interviewees); Feldon, Barbara (narrator) (1992). The Dinosaurs! Episode 1: "The Monsters Emerge" (TV-series). PBS Video, WHYY-TV.

{{cite AV media}}: External link in|title= - Bryson, Bill (2003). "Science Red in Tooth and Claw". A Short History of Nearly Everything. United States of America: Random House. ISBN 0-7679-0818-X.

- Colbert, Edwin (1984). The Great Dinosaur Hunters and Their Discoveries. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-24701-5.

- Farlow, James (1999). The Complete Dinosaur. United States of America: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-21313-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Jaffe, Mark (2000). The Gilded Dinosaur: The Fossil War Between E. D. Cope and O. C. Marsh and the Rise of American Science. New York: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 0-517-70760-8.

- Levins, Hoag (2004). "Haddonfield and The 'Bone Wars'". Levins.com. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- Mondor, Colleen (2006-01-01). "Comic Books and Thunder Lizards". BookSlut. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- Norell, Mark A. (1995). Discovering Dinosaurs in the American Museum of Natural History. New York: Alfred Knopf Publishing. ISBN 0-679-43386-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Norman, David (1991). Dinosaur!. New York: Prentice Hill. ISBN 0-13-218140-1.

- Osborn, Henry (1978). Cope: Master Naturalist : Life and Letters of Edward Drinker Cope, With a Bibliography of His Writings. Manchester, New Hampshire: Ayer Company Publishing. ISBN 0-405-10735-8.

- Penick, James (1971). "Professor Cope vs. Professor Marsh". American Heritage. 22 (5).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Preston, Douglas (1993). Dinosaurs in the Attic: An Excursion Into The American Museum of Natural History. United States of America: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-312-10456-1.

- Rajewski, Genevieve (2008). "Where Dinosaurs Roamed". Smithsonian. 39 (2): 20–26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Shor, Elizabeth (1974). The Fossil Feud Between E. D. Cope and O. C. Marsh. Detroit, Michigan: Exposition Press. ISBN 0-682-47941-1.

- Trefil, James S (2003). The Nature of Science: An A-Z Guide to the Laws and Principles Governing Our Universe. Houghton Mifflin Books. ISBN 0-618-31938-7.

- Waggoner, Ben (1999-10-22). "Bone Wars & Two Tiny Claws". Palaeontologia Electronica. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- Wilford, John Noble (1985). The Riddle of the Dinosaur. New York: Knopf Publishing. ISBN 0-394-74392-X.

- ANSP. "Bone Wars: The Cope-Marsh Rivalry". Academy of Natural Sciences. Retrieved 2008-02-19.