Tree of life (biology)

- See also Tree of life (disambiguation) for other meanings of the Tree of Life.

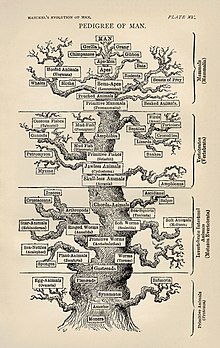

Charles Darwin believed that phylogeny, the ascent of all species through time, was expressible as a metaphor he termed the Tree of Life. The modern development of this idea is called the Phylogenetic tree.

Charles Robert Darwin's Tree of Life

An excerpt from Darwin's On the Origin of Species (originally entitled Phylogeny via Oogeny) explaining his views on the Tree of Life:

The affinities of all the beings of the same class have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this simile largely speaks the truth. The green and budding twigs may represent existing species; and those produced during former years may represent the long succession of extinct species. At each period of growth all the growing twigs have tried to branch out on all sides, and to overtop and kill the surrounding twigs and branches, in the same manner as species and groups of species have at all times overmastered other species in the great battle for life. The limbs divided into great branches, and these into lesser and lesser branches, were themselves once, when the tree was young, budding twigs; and this connection of the former and present buds by ramifying branches may well represent the classification of all extinct and living species in groups subordinate to groups. Of the many twigs which flourished when the tree was a mere bush, only two or three, now grown into great branches, yet survive and bear the other branches; so with the species which lived during long-past geological periods, very few have left living and modified descendants.

From the first growth of the tree, many a limb and branch has decayed and dropped off; and these fallen branches of various sizes may represent those whole orders, families, and genera which have now no living representatives, and which are known to us only in a fossil state. As we here and there see a thin, straggling branch springing from a fork low down in a tree, and which by some chance has been favored and is still alive on its summit, so we occasionally see an animal like the Ornithorhynchus (Platypus) or Lepidosiren (South American lungfish), which in some small degree connects by its affinities two large branches of life, and which has apparently been saved from fatal competition by having inhabited a protected station. As buds give rise by growth to fresh buds, and these, if vigorous, branch out and overtop on all sides many a feebler branch, so by generation I believe it has been with the great Tree of Life, which fills with its dead and broken branches the crust of the earth, and covers the surface with its ever-branching and beautiful ramifications.

The tree of life today

The model is still considered valid for eukaryotic life forms. The earliest branch of the eukaryote tree yields four supergroups: Plants (green and red algae, and plants), Unikonts (amoebas, fungi, and all animals—including humans), Excavates (free-living organisms and parasites), and SAR (a recently identified main group, abbreviated from Stramenopiles, Alveolates, and Rhizaria, the names of some of its members)[2].

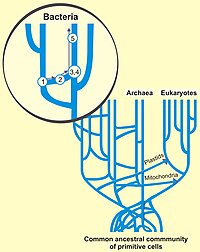

Biologists now recognize, that the prokaryotes, the bacteria and archaea , have the ability to transfer genetic information between unrelated organisms through Horizontal gene transfer (HGT). Recombination, gene loss, duplication, and gene creation are a few of the processes by which genes can be transferred within and between bacterial and archael species, causing variation that’s not due to vertical transfer. [3] There is emerging evidence of HGT occurring within the prokaryotes at the single and multicell level and the view is now emerging that the tree of life gives an incomplete picture of life's evolution. It was a useful tool in understanding the basic processes of evolution but cannot explain the full complexity of the situation.[3]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Darwin, C. (1872), pp. 170-171. The Origin of Species. Sixth Edition. The Modern Library, New York.

- ^ Apollon: The Tree of Life Has Lost a Branch

- ^ a b Graham Lawton Why Darwin was wrong about the tree of life New Scientist Magazine issue 2692 21 January 2009 [1] Accessed Feb 2009

References

- Doolittle, W. Ford, and Bapteste, Eric. Pattern pluralism and the Tree of Life hypothesis PNAS, February 13, 2007, vol. 104, no. 7, 2043-2049. ( Reported At PhyOrg.com March 12, 2007 )

External links

- Tree of Life Web Project - explore complete phylogenetic tree interactively

- Tree of Life illustration - A modern illustration of the complete tree of life.

- Science Magazine Tree of Life - Sample tree of life from Science journal.

- Science journal issue - Issue devoted to the tree of life.

- [2]-Report on recent paper on "pruning" of the tree of life model.

- The Tree of Life by Garrett Neske, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project: "presents an interactive tree of life that allows you to explore the relationships between many different kinds of organisms by allowing you to select an organism and visualize the clade to which it belongs."

- The Green Tree of Life - Hyperbolic tree The University and Jepson Herbaria