Impeachment

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2008) |

Impeachment is the first of two stages in a specific process for a legislative body to consider whether or not to forcibly remove a government official from office. The impeachment itself brings the charges against the government.

Impeachment does not necessarily result in removal from office; it is only a legal statement of charges, parallel to an indictment in criminal law. An official who is impeached faces a second legislative vote (whether by the same body or another), which determines conviction, or failure to convict, on the charges embodied by the impeachment. Most constitutions require a supermajority to convict. Although the subject of the charge is criminal action, it does not constitute a criminal trial; the only question under consideration is the removal of the individual from office, and the possibility of a subsequent vote preventing the removed official from ever again holding political office in the jurisdiction where he was removed.

The word "impeachment" derives from Latin roots expressing the idea of becoming caught or entrapped, and has analogues in the modern French verb empêcher (to prevent) and the modern English impede. Medieval popular etymology also associated it (wrongly) with derivations from the Latin impetere (to attack). (In its more frequent and more technical usage, impeachment of a person in the role of a witness is the act of challenging the honesty or credibility of that person.)

The process should not be confused with a recall election. A recall election is usually initiated by voters and can be based on "political charges", for example mismanagement, whereas impeachment is initiated by a constitutional body (usually a legislative body) and is usually, but not always, based on an indictable offense. The process of removing the official is also different.

Impeachment is an Iroquois tradition, adopted by the British after colonizing the New World. Following the British example, the constitutions of Virginia (1776) and Massachusetts (1780) and other states thereafter adopted the impeachment doctrine. In private organizations, a motion to impeach can be used to prefer charges.[1]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, it is the House of Commons that holds the power of initiating an impeachment. Any member may make accusations of any crime. The member must support the charges with evidence and move for impeachment. If the Commons carries the motion, the mover receives orders to go to the bar at the House of Lords and to impeach the accused "in the name of the House of Commons, and all the commons of the United Kingdom." However, impeachment has not been used for over two hundred years (the last impeachment trial was of Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville in 1806).

The House of Lords hears the case. The procedure used to be that the Lord Chancellor presided (or the Lord High Steward if the defendant was a peer). However since the Lord Chancellor today is no longer a judge, it is not certain who would preside over an impeachment trial today. If Parliament is not in session, then the trial is conducted by a "Court of the Lord High Steward" instead of the House of Lords (even if the defendant is not a peer).

The hearing resembles an ordinary trial: both sides may call witnesses and present evidence. At the end of the hearing the lords vote on the verdict, which is decided by a simple majority, one charge at a time. Upon being called, a lord must rise and declare "guilty, upon my honour" or "not guilty, upon my honour". After voting on all of the articles has taken place, and if the Lords find the defendant guilty, the Commons may move for judgment; the Lords may not declare the punishment until the Commons have so moved. The Lords may then decide whatever punishment they find fit, within the law. A royal pardon cannot excuse the defendant from trial, but a pardon may reprieve a convicted defendant.

In April 1977 the Young Liberals' annual conference unanimously passed a motion to call on the Liberal leader (David Steel) to move for the impeachment of Ronald King Murray QC, the Lord Advocate. Mr. Steel did not call the motion but Murray (now Lord Murray, a former Senator of the College of Justice of Scotland) agrees that the Commons still have the right to initiate an impeachment motion. On 25 August 2004, Plaid Cymru MP Adam Price announced his intention to move for the impeachment of Tony Blair for his role in involving Britain in the 2003 invasion of Iraq. In response Peter Hain, the Commons Leader, insisted that impeachment was obsolete, given modern government's responsibility to parliament. Ironically, Peter Hain had served as president of the Young Liberals when they called for the impeachment of Mr. Murray in 1977.

In 2006, General Sir Michael Rose revived the call for the impeachment of Tony Blair, then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, for leading the country into the invasion of Iraq in 2003 under allegedly false justification.

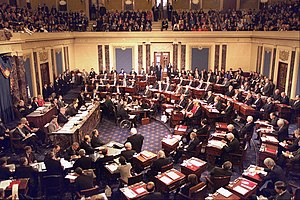

United States

Similar to the British system, Article One of the United States Constitution gives the House of Representatives the sole power of impeachment and the Senate the sole power to try convictions. Unlike the British system, conviction requires a two-thirds vote.

Impeachable offenses

In the United States, impeachment can occur both at the federal and state level. The Constitution defines impeachment at the federal level and limits impeachment to "The President, Vice President, and all civil officers of the United States" who may only be impeached and removed for "treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors". [2] Several commentators have suggested that Congress alone may decide for itself what constitutes an impeachable offense.[citation needed] In 1970, then-House Minority Leader Gerald R. Ford defined the criteria as he saw it: "An impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history."[3] Four years later, Ford would become president when President Richard Nixon resigned under the threat of impeachment.

Article III of the Constitution states that judges remain in office "during good behaviour", implying that Congress may remove a judge for bad behavior via impeachment. Whether this is the only method available to remove judges is a subject of controversy.[citation needed] The House has impeached 13 federal judges and the Senate has convicted six of them.[4]

Officials subject to impeachment

The central question regarding the Constitutional dispute about the impeachment of members of the legislature is whether members of Congress are "officers" of the United States. The Constitution grants the House the power to impeach "The President, the Vice President, and all civil Officers of the United States." [2] Many believe firmly that members of Congress are not officers of the United States.[5] Others, however, believe that members are civil officers and are subject to impeachment.[citation needed]

The House of Representatives did impeach a senator once[6]: Senator William Blount. The Senate expelled Senator Blount and, after initially hearing his impeachment, dismissed the charges for lack of jurisdiction.[7] Left unsettled was the question whether members of Congress were civil officers of the United States. The House has never impeached a member of Congress since Blount. As each House has the authority to expel its own members without involving the other chamber, expulsion has been the method used for removing Members of Congress.

Jefferson's Manual, which is integral to the House rules, states that impeachment is set in motion by charges made on the floor, charges preferred by a memorial, a member's resolution referred to a committee, a message from the president, charges transmitted from the legislature of a state or territory or from a grand jury, or from facts developed and reported by an investigating committee of the House. It further states that a proposition to impeach is a question of high privilege in the House and at once supersedes business otherwise in order under the rules governing the order of business.

Process

The impeachment process is a two-step procedure. The House of Representatives must first pass by a simple majority articles of impeachment, which constitute the formal allegation or allegations. Upon their passage, the defendant has been "impeached". Next, the Senate tries the accused. In the case of the impeachment of a president, the Chief Justice of the United States presides over the proceedings. For the impeachment of any other official, the Constitution is silent on who shall preside, suggesting that this role falls to the Senate's usual presiding officer. This may include the impeachment of the vice president, although legal theories suggest that allowing a person to be the judge in the case where she or he was the defendant would be a blatant conflict of interest. If the Vice President did not preside over an impeachment (of someone other than the President), the duties would fail to the President pro tempore of the Senate.

In order to convict the accused, a two-thirds majority of the senators present is required. Conviction automatically removes the defendant from office. Following conviction, the Senate may vote to further punish the individual by barring them from holding future federal office, elected or appointed. Conviction by the Senate does not bar criminal prosecution. Even after an accused has left office, it is possible to impeach to disqualify the person from future office or from certain emoluments of their prior office (such as a pension). If there is no charge for which a two-thirds majority of the senators present vote "guilty", the defendant is acquitted and no punishment is imposed.

History of federal impeachment proceedings

Congress regards impeachment as a power to be used only in extreme cases; the House has initiated impeachment proceedings only 62 times since 1789 (most recently against President Bill Clinton), and only occupants of the following 16 federal offices have been impeached:

- Two presidents:

- Andrew Johnson was impeached in 1868 after violating the then-newly created Tenure of Office Act. President Johnson was acquitted by the Senate, falling one vote short of the necessary 2/3 needed to remove him from office, voting 35-19 to remove him.

- Bill Clinton was impeached on December 19, 1998 by the House of Representatives on articles charging perjury (specifically, lying to a federal grand jury) by a 228–206 vote, and obstruction of justice by a 221–212 vote. The House rejected other articles. One was a count of perjury in a civil deposition in Paula Jones's sexual harassment lawsuit against Clinton (by a 205–229 vote) and an article which accused Clinton of abuse of power by a 48–285 vote. The Senate fell short of the necessary 2/3 needed to remove him from office, voting 45-55 to remove him on obstruction of justice and 50-50 on perjury.

- One cabinet officer, William W. Belknap (Secretary of War). He resigned before his trial, and was later acquitted. Allegedly most of those who voted to acquit him believed that his resignation had removed their jurisdiction.

- One Senator, William Blount, though the Senate had already expelled him.

- One Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, Samuel Chase in 1804.

- Twelve other federal judges, including Alcee Hastings, who was impeached and convicted for taking over $150,000 in bribe money in exchange for sentencing leniency. The Senate did not bar Hastings from holding future office, and Hastings won election to the House of Representatives from Florida. Hastings's name was mentioned as a possible Chairman of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, but was passed over by House Speaker-designate Nancy Pelosi, presumably because of his previous impeachment and removal. Source U.S. Senate

Many mistakenly assume Richard Nixon was impeached. While the House Judiciary Committee did approve articles of impeachment against him and did report those articles to the House of Representatives, Nixon resigned before the House could consider the impeachment resolutions and was subsequently pardoned by President Ford.

Pakistan

The country's ruling coalition said on 7 August 2008 that it would seek the impeachment of President Pervez Musharraf, alleging the U.S.-backed former general had "eroded the trust of the nation" and increasing pressure on him to resign. He resigned on 18 August 2008.

Impeaching a president requires a two-thirds majority support of lawmakers in a joint session of both houses of Parliament.

Philippines

Impeachment in the Philippines follows procedures similar to the United States. Under Sections 2 and 3, Article XI, Constitution of the Philippines, the House of Representatives of the Philippines has the exclusive power to initiate all cases of impeachment against the President, Vice President, members of the Supreme Court, members of the Constitutional Commissions (Commission on Elections, Commission on Audit), and the Ombudsman. When a third of its membership has endorsed the impeachment articles, it is then transmitted to the Senate of the Philippines which tries and decide, as impeachment tribunal, the impeachment case.[8] A main difference from US proceedings however is that only 1/3 of House members are required to approve the motion to impeach the President (as opposed to 50%+1 members in their US counterpart). In the Senate, selected members of the House of Representatives act as the prosecutors and the Senators act as judges with the Senate President and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court jointly presiding over the proceedings. Like the United States, in order to convict the official in question, a minimum of 2/3 (i.e 16 of 24 members) of the senate is required to vote in favour of conviction. If an impeachment attempt is unsuccessful or the official is acquitted, no new cases can be filed against that impeachable official for at least one full year.

Impeachable offenses and officials

The 1987 Philippine Constitution states that grounds for impeachment include bribery, graft and corruption, betrayal of public trust, and culpable violation of the Constitution. These offenses are considered "high crimes and misdemeanors" under the Philippine Constitution.

The President, the Vice President, the Supreme Court's justices, the members of the Commission on Elections, and Ombudsmen are all considered impeachable officials under the Constitution.

Impeachment proceedings and attempts

Joseph Estrada was the first Philippine president impeached by the House in 2000, but the trial ended prematurely due to outrage over a vote to open an envelope where that motion was narrowly defeated by his allies.

In 2005, 2006, 2007, and 2008, impeachment complaints were filed against President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, but none of the cases reached the required endorsement of 1/3 of the members for transmittal to, and trial by, the Senate.

Republic of Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland formal impeachment can apply only to the President. Article 12 of the Constitution of Ireland provides that, unless judged to be "permanently incapacitated" by the Supreme Court, the president can only be removed from office by the houses of the Oireachtas (parliament) and only for the commission of "stated misbehaviour". Either house of the Oireachtas may impeach the president, but only by a resolution approved by a majority of at least two-thirds of its total number of members; and a house may not consider a proposal for impeachment unless requested to do so by at least thirty of its number.

Where one house impeaches the president, the remaining house either investigates the charge or commissions another body or committee to do so. The investigating house can remove the president if it decides, by at least a two-thirds majority of its members, both that she is guilty of the charge of which she stands accused, and that the charge is sufficiently serious as to warrant her removal. To date no impeachment of an Irish president has ever taken place. The president holds a largely ceremonial office, the dignity of which is considered important, so it is likely that a president would resign from office long before undergoing formal conviction or impeachment.

Other jurisdictions

- Austria: The Austrian Federal President can be impeached by the Federal Assembly (Bundesversammlung) before the Constitutional Court. The constitution also provides for the recall of the president by a referendum. Neither of these courses has ever been taken, likely because the President is an unobtrusive and largely ceremonial figurehead who, having little power, is hardly in a position to abuse it.

- Brazil: The President of Federative Republic of Brazil can be impeached. This happened to Fernando Collor de Mello, due to evidence of bribery and misappropriation. State governors and mayors can also be impeached, though only the latter have actually been impeached.

- Croatia: President of the Republic of Croatia can be impeached. Sabor starts the impeachment process with two-thirds majority in favor of impeachment and then Constitutional Court has to accept that with two-thirds majority of justices in favor of impeachment. That never happened in history of Republic of Croatia.

- Germany: The Federal President of Germany can be impeached both by the Bundestag and by the Bundesrat for willfully violating German law. Once the Bundestag or the Bundesrat impeaches the president, the Federal Constitutional Court decides whether the President is guilty as charged and, if this is the case, whether to remove him or her from office. No such case has yet occurred, not the least because the President's functions are mostly ceremonial and he or she seldom makes controversial decisions. The Federal Constitutional Court also has the power to remove federal judges from office for willfully violating core principles of the federal constitution or a state constitution.

- India: The President of India can be impeached by the Parliament before the expiry of his term for violation of the Constitution. Other than impeachment, no other penalty can be given to the President for the violation of the Constitution. No Indian President has faced impeachment proceedings. Hence, the provisions for impeachment have never been tested.

- Iran: Member of Majlis representatives and the Supreme Leader can remove the President. In January 1980, Abolhassan Banisadr, then the president of Iran, was impeached by the Majlis representatives in June, 1981.

- Norway: Members of government, representatives of the national assembly (Stortinget) and Supreme Court judges can be impeached for criminal offences tied to their duties and committed in office, according to the Constitution of 1814, §§ 86 and 87. The procedural rules were modelled on the US rules and are quite similar to them. Impeachment has been used 8 times since 1814, last in 1927. Many argue that impeachment has fallen into desuetude.

- Romania: The President can be impeached by Parliament and is then suspended. A referendum then follows to determine whether the suspended President should be removed from office. President Traian Băsescu was recently impeached by the Parliament. A referendum was held on May 19, 2007. A large majority of the electorate voted against removing the president from office.

- Russia: The President of Russia can be impeached if both the State Duma (which initiates the impeachment process through the formation of a special investigation committee) and the Federation Council of Russia vote by a two-thirds majority in favor of impeachment and, additionally, the Supreme Court finds the President guilty of treason or a similarly heavy crime against the nation and the Constitutional Court confirms that the constitutional procedure of the impeachment process was correctly observed. In 1995-1999, the Duma made several attempts to impeach then-President Boris Yeltsin, but they never had a sufficient amount of votes for the process to reach the Federation Council.

- Taiwan: Officials can be impeached by a two-thirds vote in the Legislative Yuan together with an absolute majority in a referendum.

See also

References

- ^ Demeter, George (1969). Demeter's Manual of Parliamentary Law and Procedure, 1969 ed., p. 265

- ^ a b U.S. Constitution, Article II, Section 4

- ^ Gerald Ford's Remarks on the Impeachment of Supreme Court Justice William Douglas, April 15, 1970

- ^ List of Senate Impeachment Trials

- ^ (pdf) Testimony of M. Miller Baker before Senate committee

- ^ Senate List of Impeachment trials

- ^ The First Impeachment by Buckner F. Milton

- ^ Chan-Robles Virtual Law Library. "The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines - Article XI". Retrieved 2008-07-25.