Dinosaur Diamond

| |

| Route information | |

| Length | 512 mi[1] (824 km) |

| Existed | 2002–present |

| Location | |

| Counties | Utah: Carbon, Duchesne, Grand, Emery Colorado: Moffat, Rio Blanco, Garfield, Mesa |

| Major cities | Utah: Price, Helper, Vernal, Moab, Green River Colorado: Dinosaur, Rangely, Grand Junction, Fruita |

The Dinosaur Diamond Scenic Byway is a 512-mile[1] National Scenic Byway in the U.S. states of Utah and Colorado.[2] The highway forms a diamond-shaped loop with vertices at Moab, Helper, Vernal and Grand Junction.

The segment within Utah is known as the Dinosaur Diamond Prehistoric Highway. The segment within Colorado is known as the Dinosaur Diamond Scenic and Historic Byway. Notable features surrounding the Dinosaur Diamond include Dinosaur National Monument, the Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area, Canyonlands National Park, Arches National Park, Natural Bridges National Monument, Colorado National Monument, and several national forests.

The path of Interstate 70 in Colorado is derived from two previous highways, U.S. Highway 6 and U.S. Highway 40. US 40 was an original piece of the U.S. Highway system commissioned in 1926. The portion now numbered U.S. Highway 6 came about in 1937 when the route over Vail Pass was paved. The first route through the path of Interstate 70 in Utah was the Old Spanish Trail, a trade route between Santa Fe, New Mexico and Los Angeles, California. The trail was in common use before the Mexican-American War in 1848.

Route Description

Colorado

The following Colorado routes are included in the Colorado portion of the Dinosaur Diamond Scenic and Historic Byway:[1]

Interstate 70 between Grand Junction and the Utah state line. (I-70 runs concurrent with U.S. Highway 6 and U.S. Highway 50 in this area)

Interstate 70 between Grand Junction and the Utah state line. (I-70 runs concurrent with U.S. Highway 6 and U.S. Highway 50 in this area) U.S. Route 40 between Dinosaur and the Utah state line

U.S. Route 40 between Dinosaur and the Utah state line State Highway 64 between Dinosaur and Rangely

State Highway 64 between Dinosaur and Rangely State Highway 139 between Fruita and Rangely

State Highway 139 between Fruita and Rangely

The easternmost starting point of the Dinosaur Diamond (DD) begins in Grand Junction, Colorado on Interstate 70.[1] In the vicinity of Grand Junction are the White River, Uncompahgre, and Grand Mesa National Forests.[3] Other notable features nearby include the Powderhorn Resort, and the geologic features of Book Cliffs and Grand Mesa.

Traveling about 10 miles (16 km) westbound on I-70 will lead to Fruita, a small town within view of the Colorado National Monument,[3] which features numerous scenic hiking trails. From the trails, one may view attractions such as the Book Cliffs and Coke Ovens overlooks, and unique rock formations such as Independence Monument and the "Kissing Couple".[4] Fruita is also the home of Mike the Headless Chicken, and hosts an annual festival in his honor every May. A small statue dedicated to Mike can also be seen in the town.[5]

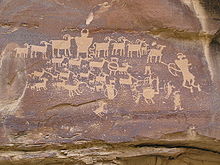

Just west of Fruita, the byway turns north onto State Highway 139, traveling 78 miles (126 km) to the next town of Rangely, and traversing the Douglas Pass.[3] Nearby attractions include the Rangely Outdoor Museum and the Canyon Pintado ("painted canyon") Historic District petroglyphs, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[6][7]

The byway continues 18 miles (29 km) northwest on State Highway 64, to the small town of Dinosaur.[3] Nearby Dinosaur is the "crown jewel" of the DD, the Dinosaur National Monument, which claims to be the most productive Jurassic Period dinosaur quarry in the world. The monument includes a walkway where visitors can view a sandstone wall embedded with over 2,000 dinosaur bones, and watch paleontologists chip away the sandstone to expose the fossilized dinosaur bones. Visitors can also see the preparation laboratory where dinosaur fossils are cleaned and preserved.[8]

Upon leaving Dinosaur, the DD continues west on U.S. Highway 40 and crosses the border into Utah.[3]

Utah

The Utah portion of the Dinosaur Diamond Prehistoric Highway is routed along these highways:[1]

Interstate 70 Between Colorado state line and Cisco, again from Crescent Junction to Green River (I-70 runs concurrent with U.S. Route 6 and U.S. Route 50 in this area)

Interstate 70 Between Colorado state line and Cisco, again from Crescent Junction to Green River (I-70 runs concurrent with U.S. Route 6 and U.S. Route 50 in this area) U.S. Route 6 from Green River to Helper

U.S. Route 6 from Green River to Helper U.S. Route 40 from Vernal to Colorado state line

U.S. Route 40 from Vernal to Colorado state line U.S. Route 191 from Moab to Vernal

U.S. Route 191 from Moab to Vernal State Route 128 from Cisco to Moab

State Route 128 from Cisco to Moab

Traveling 34 miles (55 km) west of Dinosaur, Colorado, the Dinosaur Diamond encounters the small city of Vernal, Utah. Vernal borders the western end of the Dinosaur National Monument; other notable attractions nearby include Steinaker State Park, Red Fleet State Park, Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area, and the Ashley National Forest.[3]

Continuing along the Dinosaur Diamond, U.S. Routes 40 and 191 converge within Vernal, heading west for 30 miles (48 km) to the city of Roosevelt. Roosevelt is located on the edge of the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation. Heading 29 miles (47 km) to the west is the county seat of Duchesne, located within the reservation. Nearby Duchesne are Starvation State Park[3] and Kings Peak (the highest point in Utah), which is part of the Uinta Mountain range. The Uinta Mountains are one of the few mountain ranges in the contiguous United States which run east-west, and are the highest range to do so.[9]

Within Duchesne, U.S. Routes 40 and 191 diverge, and the DD continues 55 miles (89 km) south along 191 over an un-named mountain pass, through the small town of Helper, and into the larger city of Price. The numerous attractions surrounding Price include College of Eastern Utah Prehistoric Museum,[10] Manti-La Sal National Forest, Huntington Lake State Park, Scofield State Park,[3] and Nine Mile Canyon which features numerous petroglyphs.[11] Also nearby is the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, a prehistoric mud trap which claims to be the densest concentration of Jurassic dinosaur fossils in the world.[12]

Traveling 63 miles (101 km) southeast along U.S. Route 191, the DD encounters the city of Green River.[3] Notable features surrounding Green River include the San Rafael Swell,[13] Green River State Park, and Goblin Valley State Park.[3] Also nearby is Crystal Geyser, a rare (but man-made) cold water geyser caused by the expansion of carbonized "soda pop" water within.[14] Within Green River, U.S. Route 191 converges with Interstate 70 for a short while and diverges again, south towards the city of Moab, 55 miles (89 km) from Green River.

Just south of the junction of U.S. Route 191 and State Route 128, the city of Moab features a number of nearby attractions. Arches National Park, Canyonlands National Park, Dead Horse Point State Park,[3] and the Newspaper Rock[15] and Potash Road petroglyphs.[16]

Leaving Moab, the DD continues north along State Route 128 to its terminus with I-70 in Cisco. Traveling east along I-70, before completing the "diamond" back in Grand Junction, Colorado.[3]

History

The segment within Colorado was designated the Dinosaur Diamond Scenic and Historic Byway by the Colorado Transportation Commission in 1997. The segment within Utah was designated the Dinosaur Diamond Prehistoric Highway by the Utah State Legislature in 1998. The highway was approved as a National Scenic Byway in 2002.[1]

National Scenic Byways must go through a nomination procedure, and must already be designated as a state scenic byway in order to be nominated (However, roads that meet all criteria and requirements for National designation but not State or designation criteria may be considered for national designation on a case-by-case basis).[17]

To be considered for designation "a road or highway must significantly meet at least one of the six scenic byways intrinsic qualities". The qualities are:[17]

- Scenic Quality is the heightened visual experience derived from the view of natural and manmade elements of the visual environment of the scenic byway corridor. The characteristics of the landscape are strikingly distinct and offer a pleasing and most memorable visual experience.

- Natural Quality applies to those features in the visual environment that are in a relatively undisturbed state. These features predate the arrival of human populations and may include geological formations, fossils, landform, water bodies, vegetation, and wildlife. There may be evidence of human activity, but the natural features reveal minimal disturbances.

- Historic Quality encompasses legacies of the past that are distinctly associated with physical elements of the landscape, whether natural or manmade, that are of such historic significance that they educate the viewer and stir an appreciation for the past. The historic elements reflect the actions of people and may include buildings, settlement patterns, and other examples of human activity.

- Cultural Quality is evidence and expressions of the customs or traditions of a distinct group of people. Cultural features include, but are not limited to, crafts, music, dance, rituals, festivals, speech, food, special events, or vernacular architecture.

- Archeological Quality involves those characteristics of the scenic byways corridor that are physical evidence of historic or prehistoric human life or activity. The scenic byway corridor's archeological interest, as identified through ruins, artifacts, structural remains, and other physical evidence have scientific significance that educate the viewer and stir an appreciation for the past.

- Recreational Quality involves outdoor recreational activities directly association with and dependent upon the natural and cultural elements of the corridor's landscape. The recreational activities provide opportunities for active and passive recreational experiences. They include, but are not limited to, downhill skiing, rafting, boating, fishing, and hiking. Driving the road itself may qualify as a pleasurable recreational experience. The recreational activities may be seasonal, but the quality and importance of the recreational activities as seasonal operations must be well recognized.

A "corridor management plan" must also be developed, with community involvement, and the plan "should provide for the conservation and enhancement of the byway's intrinsic qualities as well as the promotion of tourism and economic development". The plan includes, but is not limited to:[17]

- A map identifying the corridor boundaries and the location of intrinsic qualities and different land uses within the corridor.

- A strategy for maintaining and enhancing those intrinsic qualities.

- A strategy describing how existing development might be enhanced and new development might be accommodated while still preserving the intrinsic qualities of the corridor.

- A general review of the road's or highway's safety and accident record to identify any correctable faults in highway design, maintenance, or operation.

- A signage plan that demonstrates how the State will insure and make the number and placement of signs more supportive of the visitor experience.

- A narrative describing how the National Scenic Byway will be positioned for marketing.

The final step is when the highway (or highways) is approved for designation by the Secretary of Transportation.[17]

Colorado history

Interstate 70 (Colorado)

The path of I-70 in Colorado is derived from two previous highways, U.S. Highway 6 and U.S. Highway 40. US 40 was an original piece of the U.S. Highway system commissioned in 1926. The portion now numbered U.S. Highway 6 came about in 1937 when the route over Vail Pass was paved. A portion of this route was also numbered U.S. Highway 24 at the time.[18]

Colorado State Highway 139

In the 1920s, Colorado State Highway 139 was an unimproved road from US 6 at Fruita north to State Highway 64 in Rangely.[19]

Utah history

Interstate 70 (Utah)

The first route through this portion of Utah was the Old Spanish Trail, a trade route between Santa Fe, New Mexico and Los Angeles, California. The trail was in common use before the Mexican-American War in 1848.[20] Although the trail serves a different route than I-70, they were both intended to connect southern California with points further east. I-70 generally parallels the route of the Old Spanish Trail west of Crescent Junction.[21]

U.S. Route 40

The Utah State Road Commission took over the highway from Kimball Junction to Colorado in 1910 and 1911,[22] and assigned the State Route 6 designation to this route by the mid-1920s.[23] In late 1926, the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) assigned the designation of US 40 to this cross-state route, consisting of most of SR-4 and all of SR-6.[24] (The SR-6 designation remained until the 1977 renumbering; SR-4 became SR-2 in 1962 and was eliminated in favor of I-80 in 1977.)

U.S. Route 191

The road connecting Colton on SR-8 (US-50, now US-6) with SR-6 (US-40) in Duchesne became a state highway in 1910. The southwest end was moved from Colton to Castle Gate in 1912,[25] and in 1927 it was numbered State Route 33.[26] Few changes were made to the roadway, and in 1981 it became part of US-191.[25]

Utah State Route 128

Access between Moab and Castle Valley was originally via a pack trail called the Heavenly Stairway. This trail, named for a dramatic descent of over 1,000 feet (300 m), was described as beautiful, but difficult to navigate.[27] Isolated from Utah's population centers, this area depended on Grand Junction and other cities in Colorado for both everyday supplies and a market for agricultural products.[28] Moab residents pushed for a road to be built along the riverbank. By 1902, the trail was replaced with a toll road, called King's Toll Road, after Samuel King. King was an early settler who also operated the toll ferry used prior to the construction of the Dewey Bridge. Rocks inscribed with "Kings Toll Road" can still be found along the roadway. While the road did improve travel, it was not built high enough above the river level and was often flooded.[27]

References

- ^ a b c d e f "About the Scenic Byway". Dinosaurdiamond.org. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ "Dinosaur Diamond". Coloradobyways.org. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Dinosaur Diamond Scenic Byway (Map). Cartography by Tele Atlas. Google Maps. 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ "Colorado National Monument - Hiking". National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ "Mike, the Headless Chicken Fruita, Colorado". Roadsideamerica.com. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ "Canyon Pintado - Rangely". Rangely.com. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ "About Us". Rangely Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ "Dinosaur National Monument". Utah.com. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ "Kings Peak, Utah". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ "Information". College of Eastern Utah Prehistoric Museum. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ "Nine Mile Canyon Coalition". Nine Mile Canyon Coalition. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ "Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry". Utah's Castle Country. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ "Where is the Swell?". Sanrafaelswell.org. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ "Carbon-Dioxide-Driven, Cold-Water Geysers". University of California Santa Barbara. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ "Articles - Newspaper Rock". Utah Travel Industry Website. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ "Moab Secnic Auto Tours". Moab Area Travel Council. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- ^ a b c d "National Scenic Byways Program Interim Policy". Government Printing Office. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ^ Road Atlas (hosted by Broer Map Library) (Map). Rand McNally. 1946. p. 24. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

{{cite map}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonth=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Colorado (western) 1926". Broer Maps Online. 1926. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ^ von Till Warren, Elizabeth. "Old Spanish Trail History". Old Spanish Trail Association. Retrieved 2008-03-19.

- ^ "Old Spanish Trail Association - Maps". Old Spanish Trail Association. Retrieved 2008-02-28.

- ^ Utah Department of Transportation, Route 6 history, updated September 2005

- ^ Rand McNally Auto Road Atlas, 1926, accessed via the Broer Map Library

- ^ United States System of Highways, November 11, 1926

- ^ a b Utah Department of Transportation, Highway Resolutions: Template:PDFlink, updated October 2007, accessed May 2008

- ^ Utah State Legislature (1927). "Chapter 21: Designation of State Roads". Session Laws of Utah.

33. From Castle Gate northeasterly to Duchesne.

- ^ a b Daughters of Utah Pioneers (1972). Grand Memories. pp. 127, 144. OCLC 4790603.

- ^ "Utah History Resource Center – Markers and Monuments – Dewey Bridge". State of Utah. 2006-10. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)