Discovery of Neptune

The discovery of the planet Neptune remains notable because it resulted from theoretical prediction of the existence of a major solar-system body made without knowledge of any observations of the body concerned. What led to Neptune's discovery was indirect evidence from the marginal disturbing effects which it produced gravitationally on the observed motion of Uranus. The actual discovery was made on September 23, 1846 at the Berlin Observatory, by astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle (assisted by Heinrich D'Arrest), working from the mathematical predictions of Urbain Le Verrier which Galle had received just that same morning. It was a sensational moment of 19th century science and dramatic confirmation of Newtonian gravitational theory. In François Arago's apt phrase, Le Verrier had discovered a planet "with the point of his pen." Unfortunately, Le Verrier's triumph also led to a tense international dispute over priority, as shortly after the Galle/Le Verrier discovery, Astronomer Royal George Airy announced that British mathematician John Couch Adams had simultaneously made mathematical calculations similar to those of Le Verrier [1].

Before its discovery only seven major planets were known to astronomers, the furthest from the sun being Uranus. It was irregularities in the orbit of Uranus that led Adams in England privately and Le Verrier in France publicly to predict an eighth planet. It also led a British team to embark on a secret and ultimately unsuccessful race for its discovery.

Galileo's "near miss"

Galileo's drawings show that he first observed Neptune on December 28, 1612, and again on January 27, 1613; on both occasions, Galileo mistook Neptune for a fixed star when it appeared very close (in conjunction) to Jupiter in the night sky.[2] Believing it to be a fixed star, he is not credited with its discovery. At the time of his first observation in December 1612, it was stationary in the sky because it had just turned retrograde that very day; because it was only beginning its yearly retrograde cycle, Neptune's motion was far too slight to be detected with Galileo's small telescope.[3]

Earlier observations

Neptune was seen by Galileo, John Herschel and Lalande before and in 1846. On January 28, 1613, using the same telescope, Galileo noted that the distance between two supposedly "fixed" stars, a and b (Neptune), that were near Jupiter, had increased from the previous night.[4][5] He made sketches of the changing position. Hence, not only did Galileo record Neptune, but he was also the first person to detect its motion. [6]

Irregularities in Uranus's orbit

In 1821, Alexis Bouvard had published astronomical tables of the orbit of Uranus, making predictions of future positions based on Newton's laws of motion and gravitation.[7] Subsequent observations revealed substantial deviations from the tables, leading Bouvard to hypothesize some perturbing body.[8] These irregularities or "residuals", both in the planet's ecliptic longitude and in its distance from the Sun, or radius vector, might be explained by a number of hypotheses: the Sun's gravity, as described by Newton, might behave differently for a planet so distant from it central body; or it might simply be observational error; or, perhaps Uranus was being pulled, or perturbed, by an as-yet undiscovered eighth planet.

Adams in Cambridge

Adams learned of the irregularities while still an undergraduate and became convinced of the "perturbation" hypothesis. Adams believed, in the face of anything that had been attempted before, that he could use the observed data on Uranus, and utilising nothing more than Newton's law of gravitation, deduce the mass, position and orbit of the perturbing body.

After his final examinations in 1843, Adams was elected fellow of his college and spent the summer vacation in Cornwall calculating the first of six iterations.

In modern terms, the problem is an inverse problem, an attempt to deduce the parameters of a mathematical model from observed data. Though the problem is a simple one for modern mathematics after the advent of electronic computers, at the time it involved much laborious hand calculation. Adams began by assuming a nominal position for the hypothesised body, using the empirical Bode's law. He then calculated the path of Uranus using the assumed position of the perturbing body and calculated the difference between his calculated path and the observations, in modern terms the residuals. He then adjusted the characteristics of the perturbing body in a way suggested by the residuals and repeated the process, a process similar to regression analysis.

On 13 February 1845, James Challis, director of the Cambridge Observatory, requested data on the position of Uranus, for Adams, from Astronomer Royal George Biddell Airy at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich.[9] Adams certainly completed some calculations on 18 September.[9]

Supposedly, Adams communicated his work to Challis in mid-September 1845 but there is some controversy as to how. The story and date of this communication only seem to have come to light in a letter from Challis to the Athenaeum dated 17 October 1846.[10] However, no document was identified until 1904 when Sampson suggested a note in Adams's papers that describes "the New Planet" and is endorsed, in handwriting not Adams's, with the note "Received in September 1845".[11][10] Though this has often been taken to establish Adams's priority,[12][13] some historians have disputed its authenticity, on the basis that "the New Planet" was not a term current in 1845,[14] and on the basis that the note is dated only after the fact by someone other than Adams.[15] Further, the results of the calculations are different from those communicated to Airy a few weeks later.[10] Adams certainly gave Challis no detailed calculations[13] and Challis was unimpressed by the description of his method of successively approximating the position of the body, being disinclined to start a laborious observational programme at the observatory, remarking "while the labour was certain, success appeared to be so uncertain."[14]

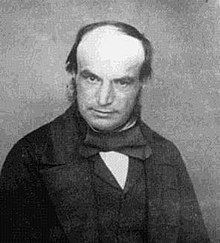

Le Verrier in Paris

Meanwhile, Urbain Le Verrier, on November 10, 1845, presented to the Académie des sciences in Paris a memoir on Uranus, showing that the pre-existing theory failed to account for its motion.[12] Unaware of Adams's work, he attempted a similar investigation, and on June 1, 1846, in a second memoir, gave the position, but not the mass or orbit, of the proposed perturbing body. Le Verrier located Neptune within one degree of its actual position.

The race for priority — London and Cambridge

Upon receiving in England the news of Le Verrier's June prediction, George Airy immediately recognized the similarity of Le Verrier's and Adams' solutions. Up until that moment, Adams' work had been little more than a curiosity, but independent confirmation from LeVerrier spurred Airy to organize a secret attempt to find the planet.[16] [17]. At a July 1846 meeting of the Board of Visitors of the Greenwich Observatory, with Challis and Sir John Herschel present, Airy suggested that Challis urgently look for the planet with the Cambridge 11.25 inch equatorial telescope, "in the hope of rescuing the matter from a state which is ... almost desperate".[18] The search was begun by a laborious method on 29 July.[13] Adams continued to work on the problem, providing the British team with six solutions in 1845 and 1846 [15] which sent Challis searching the wrong part of the sky. Only after the discovery of Neptune had been announced in Paris and Berlin did it become apparent that Neptune had been observed on August the 8th and August the 12th but because Challis lacked an up-to-date star-map, it was not recognized as a planet.[12]

The race for priority — Paris and Berlin

Le Verrier was unaware that his public confirmation of Adams' private computations had set in motion a British search for the purported planet. On 31 August, Le Verrier presented a third memoir, now giving the mass and orbit of the new body. Having been unsuccessful in his efforts to interest any French astronomer in the problem, Le Verrier finally sent his results by post to Johann Gottfried Galle at the Berlin Observatory. Galle received Le Verrier's letter on 23 September and immediately set to work observing in the region suggested by Le Verrier. Galle's student, Heinrich Louis d'Arrest, suggested that a recently drawn chart of the sky, in the region of Le Verrier's predicted location, could be compared with the current sky to seek the displacement characteristic of a planet, as opposed to a stationary star. Neptune was discovered that very night, after less than an hour of searching and less than 1 degree from the position Le Verrier had predicted, a remarkable match. After two further nights of observations in which its position and movement were verified, Galle replied to Le Verrier with astonishment: "the planet whose place you have [computed] really exists" (emphasis in original).

Disputed priority

On the announcement of the fact, Herschel, Challis and Richard Sheepshanks, foreign secretary of the Royal Astronomical Society, announced that Adams had already calculated the planet's characteristics and position. Airy, at length, published an account of the circumstances, and Adams's memoir was printed as an appendix to the Nautical Almanac.[12] However, it appears that the version published by Airy had been edited by the omission of a "crucial phrase" to disguise the fact that Adams had quoted only mean longitude and not the orbital elements.[14]

A keen controversy arose in France and England as to the merits of the two astronomers. There was much criticism of Airy in England. Adams was a diffident young man who was naturally reluctant to publish a result that would establish or ruin his career. Airy and Challis were criticised, particularly by James Glaisher,[13] as failing to exercise their proper role as mentors of a young talent. Challis was contrite but Airy defended his own behaviour, claiming that the search for a planet was not the role of the Greenwich Observatory. On the whole, Airy has been defended by his biographers.[13] In France the claims made for an unknown Englishman were resented as detracting from the credit due to Le Verrier's achievement.[12]

The Royal Society awarded Le Verrier the Copley medal in 1846 for his achievement, without mention of Adams, but Adams's academic reputation at Cambridge, and in society, was assured.[13] As the facts became known, some British astronomers pushed the view that the two astronomers had independently solved the problem of Uranus, and ascribed equal importance to each.[13][12] But Adams himself publicly acknowledged Le Verrier's priority and credit (not forgetting to mention the role of Galle) in the paper that he gave to the Royal Astronomical Society in November 1846:

I mention these dates merely to show that my results were arrived at independently, and previously to the publication of those of M. Le Verrier, and not with the intention of interfering with his just claims to the honours of the discovery ; for there is no doubt that his researches were first published to the world, and led to the actual discovery of the planet by Dr. Galle, so that the facts stated above cannot detract, in the slightest degree, from the credit due to M. Le Verrier.

— Adams (1846) [19]

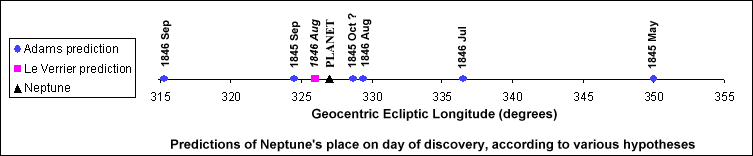

The criticism was soon afterwards made, that both Adams and Le Verrier had been over-optimistic in the precision they claimed for their calculations, and both had greatly overestimated the planet's actual distance from the sun. Further, it was suggested that they both succeeded in getting the longitude almost right only because of a "fluke of orbital timing". This criticism was discussed in detail by Danjon (1946) [20] who illustrated with a diagram and discussion that while hypothetical orbits calculated by both LeVerrier and Adams for the new planet were indeed of very different size on the whole from that of the real Neptune (and actually similar to each other), they were both much closer to the real Neptune over that crucial segment of orbit covering the interval of years for which the observations and calculations were made, than they were for the rest of the calculated orbits. So the fact that both the calculators used a much larger orbital major axis than the reality was shown to be not so important, and not the most relevant parameter.

The new planet, at first called "Le Verrier" by Francois Arago, received by consensus the neutral name of Neptune. Its mathematical prediction was a great intellectual feat, but it showed also that Newton's law of gravitation, which Airy had almost called in question, prevailed even at the limits of the solar system.[12]

Adams held no bitterness towards Challis or Airy[13] and acknowledged his own failure to convince the astronomical world:[14]

I could not expect however that practical astronomers, who were already fully occupied with important labours, would feel as much confidence in the results of my investigations, as I myself did.

By contrast, Le Verrier was arrogant and assertive, enabling the British scientific establishment to close ranks behind Adams while the French, in general, found little sympathy with Le Verrier.[14] In 1874–1876, Adams was president of the Royal Astronomical Society when it fell to him to present the gold medal of the year to Le Verrier.[12]

Contemporary disputes

Even before Neptune's discovery, in 1834, amateur astronomer Dr. Thomas Hussey speculated that one planet alone might not be enough to resolve the discrepancies in Uranus's orbit, and that a ninth planet would be required to resolve the issue.[21] In 1848, Jacques Babinet raised an objection to Le Verrier's calculations, claiming that Neptune's observed mass was smaller and its orbit larger than Le Verrier had initially predicted. He postulated, largely on simple subtraction from Le Verrier's calculations, that another planet of roughly 12 Earth masses, which he named "Hyperion", must exist beyond it.[21] Le Verrier denounced Babinet's hypothesis, saying, "[There is] absolutely nothing by which one could determine the position of another planet, barring hypotheses in which imagination played too large a part."[21]

References

- ^ Danjon, Prof. André (Director of the Paris Observatory) (1946). "Le centenaire de la découverte de Neptune". (in French) Ciel et Terre (journal) (1946) vol.62, p.369. (unknown, France). Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Alan (2001). Parallax:The Race to Measure the Cosmos. New York, New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-7133-4.

- ^ Littmann, Mark (2004). Planets Beyond: Discovering the Outer Solar System. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-4864-3602-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Unknown author, Did Galileo See Neptune?, Science News, Vol. 118, No. 15, (Oct. 11, 1980), pp. 231.

- ^ Sheehan, William & Baum, Richard, Neptune's Discovery 150 Years Later, Astronomy, September 1996, p.48.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Bouvard (1821)

- ^ [Anon.] (2001) "Bouvard, Alexis", Encyclopaedia Britannica, Deluxe CDROM edition

- ^ a b Kollerstrom, N. (2001). "A Neptune Discovery Chronology". The British Case for Co-prediction. University College London. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ^ a b c Kollerstrom, N. (2001). "Challis' Unseen Discovery". The British Case for Co-prediction. University College London. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ^ Sampson (1904)

- ^ a b c d e f g h [Anon.] (1911) "John Couch Adams, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hutchins, R. (2004). "Adams, John Couch (1819–1892)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|access=|access=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Sheehan, W.; et al. (2004). "The Case of the Pilfered Planet — Did the British steal Neptune?". Scientific American. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b Rawlins, Dennis (1992). "The Neptune Conspiracy" (PDF).

- ^ Dennis Rawlins, Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, volume 16, page 734, 1984 (first publication of British astronomer J.Hind's charge that Adams's secrecy disallows his claim).

- ^ Robert Smith, Isis, volume 80, pages 395–422, September, 1989

- ^ Smart (1947) p.59

- ^ Adams, J.C., MA, FRAS, Fellow of St Johns College, Cambridge (1846). "On the Perturbations of Uranus (p.265)". Appendices to various nautical almanacs between the years 1834 and 1854 (reprints published 1851) (note that this is a 50Mb download of the pdf scan of the nineteenth-century printed book). UK Nautical Almanac Office, 1851. Retrieved 2008-01-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Danjon, Prof. André (Director of the Paris Observatory) (1946). "Le centenaire de la découverte de Neptune". (in French) Ciel et Terre (journal) (1946) vol.62, p.369. (unknown, France). Retrieved 2008-01-23.

- ^ a b c Morton Grosser (1964). "The Search For A Planet Beyond Neptune". Isis. 55 (2): 163–183. doi:10.1086/349825. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

Bibliography

- Airy, G. B. (1847). "Account of some circumstances historically connected with the discovery of the planet exterior to Uranus". Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society. 16: 385–414.

- Airy, W. (ed.) (1896). The Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) from Project Gutenberg - [Anon.] (1911) "John Couch Adams, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- [Anon.] (2001) "Bouvard, Alexis", Encyclopaedia Britannica, Deluxe CDROM edition

- Baum, R. & Sheehan, W. (1997). In Search of Planet Vulcan: The Ghost in Newton's Clockwork Universe. Plenum.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bouvard, A. (1821), Tables astronomiques publiées par le Bureau des Longitudes de France, Paris, FR: Bachelier

- Chapman, A. (1988). "Private research and public duty: George Biddell Airy and the search for Neptune". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 19(2): 121–139.

- Dieke, S. (1970). "Heinrich Louis D' Arrest". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 295–296. ISBN 0684101149.

- Doggett, L. E. (1997) "Celestial mechanics", in Lankford, J. (ed.) (1997). History of Astronomy, an Encyclopedia. pp. 131–40.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Dreyer, J. L. E. & Turner, H. H. (eds) (1987) [1923]. History of the Royal Astronomical Society [1]: 1820–1920. pp. 161–2.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grosser, M. (1962). The Discovery of Neptune. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674212258.

- — (1970). "Adams, John Couch". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0684101149.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|author=has numeric name (help) - Harrison, H. M (1994). Voyager in Time and Space: The Life of John Couch Adams, Cambridge Astronomer. Lewes: Book Guild, ISBN 0-86332-918-7

- Hughes, D. W. (1996). "J. C. Adams, Cambridge and Neptune". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 50: 245–8. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1996.0027.

- Hutchins, R. (2004) "Adams, John Couch (1819–1892)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, accessed 23 August 2007 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- J. W. L. G. [J. W. L. Glaisher] (1882–3). "James Challis". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 43: 160–79.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Kollerstrom, Nick (2001). "Neptune's Discovery. The British Case for Co-Prediction". Unuiversity College London. Archived from the original on 2005-11-11. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- Moore, P. (1996). The Planet Neptune: An Historical Survey before Voyager. Praxis.

- Nichol, J. P. (1855). The Planet Neptune: An Exposition and History. Edinburgh: James Nichol.

- O'Connor, J. J. & Robertson, E. F. (1996). "Mathematical discovery of planets". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St. Andrews. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rawlins, Dennis (1992). "The Neptune Conspiracy" (PDF). DIO, the International Journal of Scientific History. 2 (3): 115–142.

- Rawlins, Dennis (1994). "Theft of the Neptune papers" (PDF). DIO, the International Journal of Scientific History. 4 (2): 92–102.

- Rawlins, Dennis (1999). "British Neptune Disaster File Recovered" (PDF). DIO, the International Journal of Scientific History. 9 (1): 3–25.

- Sampson, R.A. (1904). "A description of Adams's manuscripts on the perturbations of Uranus". Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society. 54: 143–161.

- Sheehan, W. & Baum, R. (September 1996). "Neptune's Discovery 150 Years Later". Astronomy: 42–49.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sheehan, W. & Thurber, S. (2007). "John Couch Adams's Asperger syndrome and the British non-discovery of Neptune". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 61(3): 285–299. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2007.0187.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sheehan, W. et al. (2004). The Case of the Pilfered Planet — Did the British steal Neptune? Scientific American

- Smart, W. M. (1946). "John Couch Adams and the discovery of Neptune". Nature. 158: 829–830. doi:10.1038/158648a0.

- — (1947). "John Couch Adams and the discovery of Neptune". Occasional Notes of the Royal Astronomical Society. 2: 33–88.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has numeric name (help) - Smith, R. W. (1989). "The Cambridge network in action: the discovery of Neptune". Isis. 80 (303): 395–422. doi:10.1086/355082.

- Standage, T. (2000). The Neptune File. Penguin Press.

- Unknown. (October 11, 1980). "Did Galileo See Neptune?". Science News. 118 (15): 231.