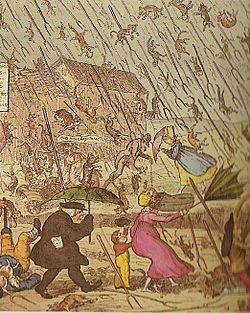

Rain of animals

Raining animals is a relatively rare meteorological phenomenon, although occurrences have been reported from many countries throughout history. One hypothesis that has been furthered to explain this phenomenon is that strong winds travelling over water sometimes pick up creatures such as fish or frogs, and carry them for up to several miles.[1] However, this primary aspect of the phenomenon has never been witnessed or scientifically tested.

The animals most likely to drop from the sky in a rainfall are fish and frogs, with birds coming third. Sometimes the animals survive the fall, especially fish, suggesting the animals are dropped shortly after extraction. Several witnesses of raining frogs describe the animals as startled, though healthy, and exhibiting relatively normal behavior shortly after the event. In some incidents, however, the animals are frozen to death or even completely encased in ice. There are examples where the product of the rain is not intact animals, but shredded body parts. Some cases occur just after storms having strong winds, especially during tornadoes.

However, there have been many unconfirmed cases in which rainfalls of animals have occurred in fair weather and in the absence of strong winds or waterspouts.

Rains of animals (as well as rains of blood or blood-like material, and similar anomalies) play a central role in the epistemological writing of Charles Fort, especially in his first book, The Book of the Damned. Fort collected stories of these events and used them both as evidence and as a metaphor in challenging the claims of scientific explanation.

Explanations

French physicist André-Marie Ampère was among the first scientists to take seriously accounts of raining animals. He tried to explain rains of frogs with a hypothesis that was eventually refined by other scientists. Speaking in front of the Society of Natural Sciences, Ampère suggested that at times frogs and toads roam the countryside in large numbers, and that the action of violent winds can pick them up and carry them great distances.[2]

More recently, a scientific explanation for the phenomenon has been developed that involves waterspouts. In effect, waterspouts are capable of capturing objects and animals and lifting them into the air. Under this theory, waterspouts or tornados, transport animals to relatively high altitudes, carrying them over large distances. The winds are capable of carrying the animals over a relatively wide area and allow them to fall in a concentrated fashion in a localized area.[3] More specifically, some tornadoes can completely suck up a pond, letting the water and animals fall some distance away in the form of a rain of animals.[4]

This hypothesis appears supported by the type of animals in these rains: small and light, usually aquatic.[5]. It is also supported by the fact that the rain of animals is often preceded by a storm. However the theory does not account for how all the animals involved in each individual incident would be from only one species, and not a group of similarly-sized animals from a single area.

In the case of birds, storms may overcome a flock in flight, especially in times of migration. The image to the right shows an example where a group of bats is overtaken by a thunderstorm.[6]. The image shows how the phenomenon could take place in some cases. In the image, the bats are in the red zone, which corresponds to winds moving away from the radar station, and enter into a mesocyclone associated with a tornado (in green). These events may occur easily with birds in flight. In contrast, it is harder to find a plausible explanation for rains of terrestrial animals; part of the enigma persists despite scientific studies.

Sometimes, scientists have been incredulous of extraordinary claims of rains of fish. For example, in the case of a rain of fish in Singapore in 1861, French naturalist Francis de Laporte de Castelnau explained that the supposed rain took place during a migration of walking catfish, which are capable of dragging themselves over the land from one puddle to another. [7] Thus, he argued that the appearance of fish on the ground immediately after a rain was easily explained, as these animals usually move over soft ground or after a rain.

Raining cats and dogs

The phrase "raining cats and dogs" is of unknown etymology.[8] A number of improbable folk etymologies have been put forward to explain the phrase,[9] for example:

- An email commonly circulated in 16th century Europe when peasant homes were commonly thatched, the home was constructed in such a manner that animals could crawl into the thatch and find shelter from the elements, and would fall out during heavy rain. Cats and dogs do not generally get into thatch.

- Drainage systems on buildings in 17th century Europe were poor, and may have disgorged their contents during heavy showers, including the corpses of any animals that had accumulated in them. This occurrence is documented in Johnathan Swift's 1710 poem 'Description of a City Shower', in which he describes "Drowned puppies, stinking sprats, all drenched in mud,/Dead cats and turnip-tops come tumbling down the flood."

- The Greek word Katadoupoi, referring to the waterfalls on the Nile,[8] sounds similar to "cats and dogs"

- The Greek phrase "kata doksa", which means "contrary to expectation" is often applied to heavy rain, but there is no evidence to support the theory that it was borrowed by English speakers.[8]

Occurrences

The following list is a selection of examples.

Fish

Frogs and toads

- Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan, June 2009 (Occurrences reported throughout the month) [12]

Others

- An unidentified animal (thought to be a cow) fell in California ripped to tiny pieces on August 1 1869; a similar incident was reported in Olympian Springs, Bath County, Kentucky in 1876[13]

- Jellyfish fell from the sky in Bath, England, in 1894[14]

- Worms dropped from the sky in Jennings, Louisiana, on July 11, 2007.[15]

In fiction

- Raining animals are relatively common in Terry Pratchett's Discworld. The explanation given is magical weather. One small village in the Ramtops operates a successful fish cannery due to regular rains of fish.[16] The Ommnian religion includes several accounts of religious figures being saved by miraculous rains of animals, one being an elephant.[17] Other items include bedsteads, cake and tinned sardines.[18]

- Fish fell from the sky in Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami.

- In the Red Dwarf episode Confidence and Paranoia, fish rain in Lister's sleeping quarters.

- Raining frogs are shown in the 1999 New Line Cinema movie, Magnolia. Frogs, and a gun, raining down causing havoc on drivers and commuters alike.

- In the role-playing game The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion, the player can do an optional quest given by a mischievous god-like being—known in the game as a "Deadra Lord"—which involves playing prank on a small, peaceful-yet-superstitious village. The player is told to perform certain actions that will fulfill a prophecy within the village that is believed to herald the end of the world, thus causing all of the villagers to panic. The final event foretold in the prophecy is flaming dogs raining from the sky, which, unlike the other events of the prophecy, is achieved by the Daedra Lord himself and his powers.

See also

- Exploding animals

- Magnolia

- The Fortean Times

- "It's Raining Men"

- Red rain in Kerala

- Star jelly

- Honduras Rain of Fishes

- Cattle mutilation

References

- ^ How can it rain fish?

- ^ «Les pluies de crapauds» Template:Fr icon.

- ^ Supernatural World uses this theory to explain a rain of fishes in Norfolk on August 8, 2000.

- ^ Orsy Campos Rivas includes this explanation in the article Lo que la lluvia regala a Yoro, which discusses a rain of fishes that occurs annually in Honduras. Hablemos onlineTemplate:Es

- ^ Angwin, Richard Wiltshire weather - BBC, July 15, 2003

- ^ Bat-eating Supercell, National Weather Service, (March 19 2006).

- ^ Comptes Rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l’Académie des sciences 52:880-81, 1861 Template:Fr icon.

- ^ a b c Raining Cats and Dogs, Anatoly Liberman

- ^ "Life in the 1500s". Snopes.com. 2007.

- ^ McAtee, Waldo L. (May 1917). "Showers of Organic Matter" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 45 (5): 223. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- ^ "Rained Fish", AP report in the Lowell (Mass.) Sun, May 16, 1900, p4

- ^ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/howaboutthat/5491846/Sky-rains-tadpoles-over-Japan.html

- ^ Fort, Charles (1919). "Ch. 4". The Book of the Damned. sacred-texts.com. pp. 44–6.

- ^ Fort, Charles (1919). "Ch. 4". The Book of the Damned. sacred-texts.com. p. 48.

- ^ "Worms Fall from the Sky in Jennings". WAFB Channel 9. 07 July 2007. Retrieved 12 December 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Pratchett, Terry (1997). The Discworld Companion. Books Britain. p. 319. ISBN 0575600306.

- ^ Pratchett, Terry (1998). Jingo. London: Corgi. pp. 252–3. ISBN 055214598X.

- ^ Pratchett, Terry (1998). Jingo. London: Corgi. p. 241. ISBN 055214598X.

External references

- Raining cats and dogs

- Raining animals in the British Isles

- BBC report on raining fish

- BBC Wiltshire report on raining animals

- BBC Bristol

- BBC Overview

- A review on the American perspective

- Fish rain

- Honduras rain of Fishes

- Its Raining Frogs!

Bibliography

- The Fortean Times. [citation needed]