Planetary science

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2009) |

Planetary science is the scientific study of planets, moons, and planetary systems, in particular those of the Solar System. It studies objects ranging in size from micrometeoroids to gas giants, aiming to determine their composition, dynamics, formation, interrelations and history. It is a strongly interdisciplinary field, originally growing from astronomy and earth science, but which now incorporates many disciplines, including planetary astronomy, planetary geology (together with geochemistry, geophysics and geomorphology as applied to planets), atmospheric science, theoretical planetary science, and the study of extrasolar planets. Allied disciplines include space physics, when concerned with the effects of the Sun on the bodies of the Solar System, and astrobiology.

There are interrelated observational and theoretical branches of planetary science. Observational research can involve a combination of space exploration, predominantly with robotic spacecraft missions using remote sensing, and comparative, experimental work in Earth-based laboratories. The theoretical component involves considerable computer simulation and mathematical modelling.

Planetary scientists are generally located in the astronomy and physics or earth sciences departments of universities or research centres, though there are several purely planetary science institutes worldwide. There are several major conferences each year, and a wide range of peer-reviewed journals.

History

The history of planetary science may be said to have begun with the the Ancient Greek philosopher Democritus, who is reported by Hippolytus as saying

"The ordered worlds are boundless and differ in size, and that in some there is neither sun nor moon, but that in others, both are greater than with us, and yet with others more in number. And that the intervals between the ordered worlds are unequal, here more and there less, and that some increase, others flourish and others decay, and here they come into being and there they are eclipsed. But that they are destroyed by colliding with one another. And that some ordered worlds are bare of animals and plants and all water."[1]

In more modern times, planetary science began in astronomy, from studies of the unresolved planets. In this sense, the original planetary astronomer would be Galileo, who discovered the four largest moons of Jupiter, the mountains on the Moon, and first observed the rings of Saturn, all objects of intense later study. Advances in telescope construction and instrumental resolution gradually allowed increased identification of the atmospheric and surface details of the planets. The Moon was initially the most heavily studied, as it always exhibited details on its surface, due to its proximity to the Earth, and the technological improvements gradually produced more detailed lunar geological knowledge. In this scientific process, the main instruments were astronomical optical telescopes (and later radio telescopes) and finally robotic exploratory spacecraft.

The Solar System has now been relatively well-studied, and a good overall understanding of the formation and evolution of this planetary system exists. However, there are large numbers of unsolved questions,[2] and the rate of new discoveries is very high, partly due to the large number of interplanetary spacecraft currently exploring the Solar System.

Disciplines

Planetary astronomy

This is both an observational and a theoretical science. Observational researchers are predominantly concerned with the study of the small bodies of the solar system: those that are observed by telescopes, both optical and radio, so that characteristics of these bodies such as shape, spin, surface materials and weathering are determined, and the history of their formation and evolution can be understood.

Theoretical planetary astronomy is concerned with dynamics: the application of the principles of celestial mechanics to the Solar System and extrasolar planetary systems.

Planetary geology

The best known research topics of planetary geology deal with the planetary bodies in the near vicinity of the Earth: the Moon, and the two neighbouring planets: Venus and Mars. Of these, the Moon was studied first, using methods developed earlier on the Earth.

Geomorphology

Geomorphology studies the features on planetary surfaces and reconstructs the history of their formation, inferring the physical processes that acted on the surface. Planetary geomorphology includes study of several classes of surface feature:

- Impact features (multi-ringed basins, craters)

- Volcanic and tectonic features (lava flows, fissures, rilles)

- Space weathering - erosional effects generated by the harsh environment of space (continuous micrometeorite bombardment, high-energy particle rain, impact gardening). For example, the thin dust cover on the surface of the lunar regolith is a result of micrometeorite bombardment.

- Hydrological features: the liquid involved can range from water to hydrocarbon and ammonia, depending on the location within the Solar System.

The history of a planetary surface can be deciphered by mapping features from top to bottom according to their deposition sequence, as first determined on terrestrial strata by Nicolas Steno. For example, stratigraphic mapping prepared the Apollo astronauts for the field geology they would encounter on their lunar missions. Overlapping sequences were identified on images taken by the Lunar Orbiter program, and these were used to prepare a lunar stratigraphic column and geological map of the Moon.

Cosmochemistry, geochemistry and petrology

One of the main problems when generating hypotheses on the formation and evolution of objects in the Solar System is the lack of samples that can be analysed in the laboratory, where a large suite of tools are available and the full body of knowledge derived from terrestrial geology can be brought to bear. Fortunately, direct samples from the Moon, asteroids and Mars are present on Earth, removed from their parent bodies and delivered as meteorites. Some of these have suffered contamination from the oxidising effect of Earth's atmosphere and the infiltration of the biosphere, but those meteorites collected in the last few decades from Antarctica are almost entirely pristine.

The different types of meteorite that originate from the asteroid belt cover almost all parts of the structure of differentiated bodies: meteorites even exist that come from the core-mantle boundary (pallasites). The combination of geochemistry and observational astronomy has also made it possible to trace the HED meteorites back to a specific asteroid in the main belt, 4 Vesta.

The comparatively few known Martian meteorites have provided insight into the geochemical composition of the Martian crust, although the unavoidable lack of information about their points of origin on the diverse Martian surface has meant that they do not provide more detailed constraints on theories of the evolution of the Martian lithosphere. About 50 Martian meteorites have been identified, as of 2008.[citation needed]

During the Apollo era, in the Apollo program, 384 kilograms of lunar samples were collected and transported to the Earth, and 3 Soviet Luna robots also delivered regolith samples from the Moon. These samples provide the most comprehensive record of the composition of any Solar System body beside the Earth. About 100 paired lunar meteorites are also known, as of 2008.[citation needed]

Geophysics

Space probes made it possible to collect data not only the visible light region, but in other areas of the electromagnetic spectrum. The planets can be characterized by their force fields: gravity and their magnetic fields, which are studied through geophysics and space physics.

Measuring the changes in acceleration experienced by spacecraft as they orbit has allowed fine details of the gravity fields of the planets to be mapped. For example, in the 1970s, the gravity field disturbances above lunar maria were measured through lunar orbiters, which lead to the discovery of concentrations of mass, mascons, beneath the Imbrium, Serenitatis, Crisium, Nectaris and Humorum basins.

If a planet's magnetic field is sufficiently strong, its interaction with the solar wind forms a magnetosphere around a planet. Early space probes discovered the gross dimensions of the terrestrial magnetic field, which extends about 10 Earth radiii towards the Sun. The solar wind, a stream of charged particles, streams out and around the terrestrial magnetic field, and continues behind the magnetic tail, hundreds of Earth radii downstream. Inside the magnetosphere, there are relatively dense regions of solar wind particles, the Van Allen radiation belts.

Atmospheric science

The atmosphere is an important transitional zone between the solid planetary surface and the higher rarefied ionizing and radiation belts. Not all planets have atmospheres: their existence depends on the mass of the planet, and the planet's distance from the Sun — too distant and frozen atmospheres occur. Besides the four gas giant planets, almost all of the terrestrial planets (Earth, Venus, and Mars) have significant atmospheres. Two moons have significant atmospheres: Saturn's moon Titan and Neptune's moon Triton. A tenuous atmosphere exists around Mercury.

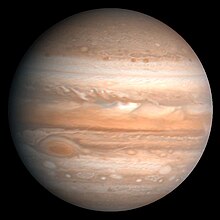

The effects of the rotation rate of a planet about its axis can be seen in atmospheric streams and currents. Seen from space, these features show as bands and eddies in the cloud system, and are particularly visible on Jupiter and Saturn.

Comparative planetary science

Planetary science frequently makes use of the method of comparison to give greater understanding of the object of study. This can involve comparing the dense atmospheres of Earth and Saturn's moon Titan, the evolution of outer Solar System objects at different distances from the Sun, or the geomorphology of the surfaces of the terrestrial planets, to give only a few examples.

The main comparison that can be made is to features on the Earth, as it is much more accessible and allows a much greater range of measurements to be made. Earth analogue studies are particularly common in planetary geology, geomorphology, and also in atmospheric science.

Professional activity

Journals

- Icarus

- Journal of Geophysical Research—Planets

- Earth and Planetary Science Letters

- Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta

- Meteoritics and Planetary Science

Professional bodies

- Division for Planetary Sciences (DPS) of the American Astronomical Society

- Meteoritical Society

- Europlanet

Major conferences

- Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC), organized by the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston. Held annually since 1970, occurs in March.

- Meteoritical Society annual meeting, held during the Northern Hemisphere summer, generally alternating between North America and Europe.

- European Planetary Science Congress (EPSC), held annually around September at a location within Europe.

- DPS annual meeting, held around October at a different location each year, predominantly within the mainland US.

Smaller workshops and conferences on particular fields occur worldwide throughout the year.

Major institutions

This non-exhaustive list includes those institutions and universities with major groups of people working in planetary science.

- European Space Agency

- NASA: Considerable number of research groups, including the JPL, GSFC, Ames

- Lunar and Planetary Institute

- Lunar and Planetary Lab at the University of Arizona

- UCLA

- Caltech's Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences

- Brown University Planetary Geosciences Group

- Center for Planetary Research (Copenhagen University)

- University of Central Florida - Planetary Sciences Group

Terminology

When the discipline concerns itself with a particular celestial body, a specialized prefix is sometimes used (in words like "heliosphere", or "areographic"). Only the commonly used prefixes are listed below.

Basic concepts

- Asteroid

- Celestial mechanics

- Comet

- Extrasolar planet

- Gas giant

- Icy moon

- Kuiper belt

- Magnetosphere

- Planet

- Planetary differentiation

- Planetary system

- Definition of a planet

- Space weather

- Terrestrial planet

References

- ^ Hippolytus (Antipope) (1921). Philosophumena. Vol. 1. Original from Harvard University.: Society for promoting Christian knowledge. Retrieved Digitized May 9, 2006.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Stern, Alan. "Ten Things I Wish We Really Knew In Planetary Science". Retrieved 2009-05-22.

Further reading

- Basilevsky, A. T.,& J. W. Head (1995): Regional and global stratigraphy of Venus: a preliminary assessment and implications for the geological history of Venus Planetary and Space Science 43/12, pp. 1523-1553

- Basilevsky, A. T.,& J. W. Head (1998): The geologic history of Venus: A stratigraphic view JGR-Planets Vol. 103 , No. E4 , p. 8531

- Basilevsky, A. T.,& J. W. Head (2002): Venus: Timing and rates of geologic activity Geology; November 2002; v. 30; no. 11; p. 1015–1018;

- Frey, H. V., E. L. Frey, W. K. Hartmann & K. L. T. Tanaka (2003): Evidence for buried "Pre-Noachian" crust pre-dating the oldest observed surface units on Mars Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIV 1848

- Gradstein, F. M., James G. Ogg, Alan G. Smith, Wouter Bleeker & Lucas J. Lourens (2004): A new Geologic Time Scale, with special reference to Precambrian and Neogene Episodes, Vol. 27, no. 2.

- Hansen V. L. & Young D. A. (2007): Venus's evolution: A synthesis. Special Paper 419: Convergent Margin Terranes and Associated Regions: A Tribute to W.G. Ernst: Vol. 419, No. 0 pp. 255–273.

- Hartmann, W. K. & Neukum, G. (2001): Cratering Chronology and the Evolution of Mars. Space Science Reviews, 96, 165–194.

- Hartman, W. K. (2005): Moons and Planets. 5th Edition. Thomson Brooks/Cole.

- Head J. W. & Basilevsky, A. T (1999): A model for the geological history of Venus from stratigraphic relationship: comparison geophysical mechanisms LPSC XXX #1390

- Mutch T.A., Arvidson R., Head J., Jones K.,& Saunders S. (1977): The Geology of Mars Princeton University Press

- Offield, T. W. & Pohn, H. A. (1970): Lunar crater morphology and relative-age determiantion of lunar geologic units U.S. Geol. Survey Prof. Paper No. 700-C. pp. C153-C169. Washington;

- Phillips, R. J., R. F. Raubertas, R. E. Arvidson, I. C. Sarkar, R. R. Herrick, N. Izenberg, and R. E. Grimm (1992): Impact craters and Venus resurfacing history, J. Geophys. Res., 97, 15,923-15,948

- Scott, D. H. & Carr, M. H. (1977): The New Geologic Map of Mars (1:25 Million Scale). Technical report.

- Scott, D. H. & Tanaka, K. L. (1986): Geological Map of the Western Equatorial Region of Mars (1:15,000,000), USGS.

- Shoemaker, E.M., & Hackman, R.J., (1962):, Stratigraphic basis for a lunar time scale, in *Kopal, Zdenek, and Mikhailov, Z.K., eds., (1960): The Moon — Intern. Astronom. Union Symposium 14, Leningrad, 1960, Proc.: New York, Academic Press, p. 289- 300.

- Spudis, P.D. & J.E. Guest, (1988):. Stratigraphy and geologic history of Mercury, in Mercury, F. Vilas, C.R. Chapman, and M.S. Matthews, eds., Univ. of Arizona Press, Tucson, pp. 118-164.

- Spudis, P. D.& Strobell, M. E. (1984): New Identification of Ancient Multi-Ring Basins on Mercury and Implications for Geologic Evolution. LPSC XV, P. 814-815

- Spudis, P. (2001): The geological history of mercury. Mercury: Space Environment, Surface, and Interior, LPJ Conference, #8029.

- Tanaka K. L. (ed.) (1994): The Venus Geologic Mappers’ Handbook. Second Edition. Open–File Report 94-438 NASA.

- Tanaka K. L. 2001: The Stratigraphy of Mars LPSC 32, #1695, http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2001/pdf/1695.pdf

- Tanaka K. L. & J. A. Skinner (2003): Mars: Updating geologic mapping approaches and the formal stratigraphic scheme. Sixth International Conference on Mars #3129

- Wagner R. J., U. Wolf, & G. Neukum (2002): Time-stratigraphy and impact cratering chronology of Mercury. Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIII 1575

- Wilhelms D. E. (1970): Summary of Lunar Stratigraphy — Telescopic Observations. U.S. Geol. Survey Prof. Papers No. 599-F., Washington;

- Wilhelms D. (1987): Geologic History of the Moon, US Geological Survey Professional Paper 1348, http://ser.sese.asu.edu/GHM/

- Wilhelms D. E.& McCauley J. F. (1971): Geologic Map of the Near Side of the Moon. USGS Maps No. I-703, Washington;

See also

External links

- Planetary Science Research Discoveries (articles)

- The Planetary Society (world's largest space-interest group: see also their active news blog)

- Planetary Exploration Newsletter (PSI-published professional newsletter, weekly distribution)

- Women in Planetary Science (professional networking and news)