Wilhelm Schickard

Wilhelm Schickard (22 April 1592 – 24 October 1635) was a German polymath who built one of the first calculating machines in 1623.

Life

Schickard was born in Herrenberg and educated at the University of Tübingen, receiving his first degree, B.A. in 1609 and M.A. in 1611. He studied theology and oriental languages at Tübingen until 1613. In 1613 he became a Lutheran minister continuing his work with the church until 1619 when he was appointed professor of Hebrew at the University of Tübingen.

Schickard was a universal scientist and taught biblical languages such as Aramaic as well as Hebrew at Tübingen. In 1631 he was appointed professor of astronomy at the University of Tübingen. His research was broad and included astronomy, mathematics and surveying. He invented many machines such as one for calculating astronomical dates and one for Hebrew grammar. He made significant advances in mapmaking, producing maps which were far more accurate than those which were previously available at the time. [1]

He was, among his other skills, a renowned wood and copperplate engraver.[1]

Wilhelm Schickard died of the bubonic plague in Tübingen, 24 October in 1635 or maybe one day earlier.[1] In 1651, Giovanni Riccioli named the lunar crater Schickard after him.

Political theory

In 1625 Schickard, a Christian Hebraist, published an influential treatise, Mishpat ha-melek, Jus regium Hebraeorum (Title in both Hebrew and Latin: The King's Law) in which he uses the Talmud and rabbinical literature to analyze ancient Hebrew political theory.[2] Schickard argues that the Bible supports monarchy.[3]

Calculating machine

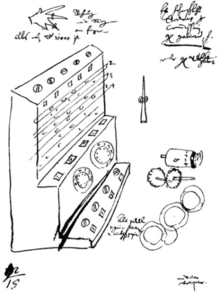

In 1623, Schickard invented a calculating machine, called by his contemporaries the Speeding Clock or Calculating Clock. It preceded the less versatile Pascaline of Pascal and Leibniz's Stepped Reckoner by twenty years.

Schickard's letters to Johannes Kepler show how to use the machine for calculating astronomical tables. The machine could add and subtract six-digit numbers, and indicated an overflow of this capacity by ringing a bell; to add more complex calculations, a set of Napier's bones were mounted on it. Schickard's letters mention that the original machine was destroyed in a fire while still incomplete. The designs were lost until the 19th century; a working replica was finally constructed in 1960.

Schickard's machine was not programmable - the first design for a programmable computer came roughly 200 years later, and was provided by Charles Babbage. The first working program-controlled machine was completed more than three centuries later, by Konrad Zuse, who created the Z3 in 1941.

The Institute for Computer Science at the University of Tübingen is called the Wilhelm-Schickard-Institut für Informatik in his honor.

References

- ^ a b c History of Computing Foundation. "Wilhelm Schickard entry at The History of Computing Project". Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ^ Eric Nelson, "Talmudical Commonwealthsmen and the Rise of Republican Exclusivism, The Historical Journal, 50, 4 (2007), p. 826

- ^ Eric Nelson, "Talmudical Commonwealthsmen and the Rise of Republican Exclusivism, The Historical Journal, 50, 4 (2007), p. 827