Confucianism

Confucianism (Chinese: 儒家; pinyin: Rújiā) is a Chinese ethical and philosophical system developed from the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius (Kǒng Fūzǐ, or K'ung-fu-tzu, lit. "Master Kong", 551–479 BC). It is a complex system of moral, social, political, philosophical, and quasi-religious thought that has had tremendous influence on the culture and history of East Asia. It might be considered a state religion of some East Asian countries, because of governmental promotion of Confucian values.

Cultures and countries strongly influenced by Confucianism include China (mainland), Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam, as well as various territories settled predominantly by Chinese people, such as Singapore. Japan was influenced by Confucianism in a different way. The basic teachings of Confucianism stress the importance of education for moral development of the individual so that the state can be governed by moral virtue rather than by the use of coercive laws.[1] Template:ChineseText

The Rites

Lead the people with administrative injunctions and put them in their place with penal law, and they will avoid punishments but will be without a sense of shame. Lead them with excellence and put them in their place through roles and ritual practices, and in addition to developing a sense of shame, they will order themselves harmoniously. (Analects II, 3)

The above quotations explain an essential difference between legalism and ritualism, and points to a key difference between European-based and East Asian societies, particularly in the realm of an individual's moral compass and accountability before the law. As with all translations of literature from ancient sources, excessively literal analysis of one particular translation may lead to unfounded conclusions.

Translations from the 17th century to the present have varied widely. Comparison of these many sources is needed for a true "general consensus" of what message Confucius meant to imply.

Confucius argued that under law, external authorities administer punishments after illegal actions, so people generally behave well without understanding reasons why they should; whereas with ritual, patterns of behavior are internalized and exert their influence before actions are taken, so people behave properly because they fear shame and want to avoid losing face. In this sense, "rite" (Chinese: 禮; pinyin: lǐ) is an ideal form of social norm.

The Chinese character for "rites", or "ritual", previously had the religious meaning of "sacrifice". Its Confucian meaning ranges from politeness and propriety to the understanding of each person's correct place in society. Externally, ritual is used to distinguish between people; their usage allows people to know at all times who is the younger and who the elder, who is the guest and who the host and so forth. Internally, rites indicate to people their duty amongst others and what to expect from them.

Internalization is the main process in ritual. Formalized behavior becomes progressively internalized, desires are channeled and personal cultivation becomes the mark of social correctness. Though this idea conflicts with the common saying that "the cowl does not make the monk," in Confucianism sincerity is what enables behavior to be absorbed by individuals. Obeying ritual with sincerity makes ritual the most powerful way to cultivate oneself:

Respectfulness, without the Rites, becomes laborious bustle; carefulness, without the Rites, become timidity; boldness, without the Rites, becomes insubordination; straightforwardness, without the Rites, becomes rudeness. (Analects VIII, 2)

Ritual can be seen as a means to find the balance between opposing qualities that might otherwise lead to conflict. It divides people into categories, and builds hierarchical relationships through protocols and ceremonies, assigning everyone a place in society and a proper form of behavior. Music, which seems to have played a significant role in Confucius' life, is given as an exception, as it transcends such boundaries and "unifies the hearts".

Although the Analects heavily promote the rites, Confucius himself often behaved other than in accord with

Governance

To govern by virtue, let us compare it to the North Star: it stays in its place, while the myriad stars wait upon it. (Analects II, 1)

Another key Confucian concept is that in order to govern others one must first govern oneself. When developed sufficiently, the king's personal virtue spreads beneficent influence throughout the kingdom. This idea is developed further in the Great Learning, and is tightly linked with the Taoist concept of wu wei (simplified Chinese: 无为; traditional Chinese: 無為; pinyin: wú wéi): the less the king does, the more gets done. By being the "calm center" around which the kingdom turns, the king allows everything to function smoothly and avoids having to tamper with the individual parts of the whole.

This idea may be traced back to early Chinese shamanistic beliefs, such as the king being the axle between the sky, human beings, and the Earth. The very Chinese character for "king" (Chinese: 王; pinyin: wáng) shows the three levels of the universe, united by a single line. Another complementary view is that this idea may have been used by ministers and counselors to deter aristocratic whims that would otherwise be to the detriment of the state's people.

Meritocracy

In teaching, there should be no distinction of classes. (Analects XV, 39)

Although Confucius claimed that he never invented anything but was only transmitting ancient knowledge (see Analects VII, 1), he did produce a number of new ideas. Many European and American admirers such as Voltaire and H. G. Creel point to the revolutionary idea of replacing nobility of blood with nobility of virtue. Jūnzǐ (君子, lit. "lord's child"), which originally signified the younger, non-inheriting, offspring of a noble, became, in Confucius' work, an epithet having much the same meaning and evolution as the English "gentleman". A virtuous plebeian who cultivates his qualities can be a "gentleman", while a shameless son of the king is only a "small man". That he admitted students of different classes as disciples is a clear demonstration that he fought against the feudal structures that defined pre-imperial Chinese society.

Another new idea, that of meritocracy, led to the introduction of the Imperial examination system in China. This system allowed anyone who passed an examination to become a government officer, a position which would bring wealth and honour to the whole family. The Chinese Imperial examination system seems to have been started in 165 BC, when certain candidates for public office were called to the Chinese capital for examination of their moral excellence by the emperor. Over the following centuries the system grew until finally almost anyone who wished to become an official had to prove his worth by passing written government examinations.

His achievement was the setting up of a school that produced statesmen with a strong sense of patriotism and duty, known as Rujia (Chinese: 儒家; pinyin: Rújiā). During the Warring States Period and the early Han Dynasty, China grew greatly and the need arose for a solid and centralized corporation of government officers able to read and write administrative papers. As a result, Confucianism was promoted by the emperor and the men its doctrines produced became an effective counter to the remaining feudal aristocrats who threatened the unity of the imperial state.

Since then Confucianism has been used as a kind of "state religion", with authoritarianism, a kind of legitimism, paternalism, and submission to authority used as political tools to rule China. Most Chinese emperors used a mix of Legalism and Confucianism as their ruling doctrine, often with the latter embellishing the former.

Themes in Confucian thought

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2009) |

A simple way to appreciate Confucian thought is to consider it as being based on varying levels of honesty. In practice, the elements of Confucianism accumulated over time and matured into the following forms:

Ritual

In Confucianism the term "ritual" (Chinese: 禮; pinyin: lǐ) was soon extended to include secular ceremonial behavior, and eventually referred also to the propriety or politeness which colors everyday life. Rituals were codified and treated as a comprehensive system of norms. Confucius himself tried to revive the etiquette of earlier dynasties. After his death, people regarded him as a great authority on ritual behaviors.

It is important to note that "ritual" has developed a specialized meaning in Confucianism, as opposed to its usual religious meanings. In Confucianism, the acts of everyday life are considered ritual. Rituals are not necessarily regimented or arbitrary practices, but the routines that people often engage in, knowingly or unknowingly, during the normal course of their lives. Shaping the rituals in a way that leads to a content and healthy society, and to content and healthy people, is one purpose of Confucian philosophy..

Relationships

Relationships are central to Confucianism. Particular duties arise from one's particular situation in relation to others. The individual stands simultaneously in several different relationships with different people: as a junior in relation to parents and elders, and as a senior in relation to younger siblings, students, and others. While juniors are considered in Confucianism to owe their seniors reverence, seniors also have duties of benevolence and concern toward juniors. This theme of mutuality is prevalent in East Asian cultures even to this day.

Social harmony—the great goal of Confucianism—therefore results in part from every individual knowing his or her place in the social order, and playing his or her part well. When Duke Jing of Qi asked about government, by which he meant proper administration so as to bring social harmony, Confucius replied:

There is government, when the prince is prince, and the minister is minister; when the father is father, and the son is son. (Analects XII, 11, trans. Legge)

Filial piety

"Filial piety" (Chinese: 孝; pinyin: xiào) is considered among the greatest of virtues and must be shown towards both the living and the dead (including even remote ancestors). The term "filial" (meaning "of a child") characterizes the respect that a child, originally a son, should show to his parents. This relationship was extended by analogy to a series of five relationships (Chinese: 五倫; pinyin: wǔlún):[2]

The Five Bonds

- Ruler to Subject

- Father to Son

- Husband to Wife

- Elder Brother to Younger Brother

- Friend to Friend

Specific duties were prescribed to each of the participants in these sets of relationships. Such duties were also extended to the dead, where the living stood as sons to their deceased family. This led to the veneration of ancestors. The only relationship where respect for elders wasn't stressed was the Friend to Friend relationship. In all other relationships, high reverence was held for elders.

In time filial piety was also built into the Chinese legal system: a criminal would be punished more harshly if the culprit had committed the crime against a parent, while fathers often exercised enormous power over their children. Much the same was true of other unequal relationships.

The main source of our knowledge of the importance of filial piety is The Book of Filial Piety, a work attributed to Confucius and his son but almost certainly written in the 3rd century BCE. The Analects, the main source of the Confucianism of Confucius, actually has little to say on the matter of filial piety and some sources believe the concept was focused on later thinkers as a response to Mohism.

Filial piety has continued to play a central role in Confucian thinking to the present day.

Loyalty

Loyalty (Chinese: 忠; pinyin: zhōng) is the equivalent of filial piety on a different plane. It is particularly relevant for the social class to which most of Confucius' students belonged, because the only way for an ambitious young scholar to make his way in the Confucian Chinese world was to enter a ruler's civil service. Like filial piety, however, loyalty was often subverted by the autocratic regimes of China. Confucius had advocated a sensitivity to the realpolitik of the class relations in his time; he did not propose that "might makes right", but that a superior who had received the "Mandate of Heaven" (see below) should be obeyed because of his moral rectitude.

In later ages, however, emphasis was placed more on the obligations of the ruled to the ruler, and less on the ruler's obligations to the ruled.

Loyalty was also an extension of one's duties to friends, family, and spouse. Loyalty to one's family came first, then to one's spouse, then to one's ruler, and lastly to one's friends. Loyalty was considered one of the greater human virtues.

Confucius also realized that loyalty and filial piety can potentially conflict.

Humanity

Confucius was concerned with people's individual development, which he maintained took place within the context of human relationships. Ritual and filial piety are indeed the ways in which one should act towards others, but from an underlying attitude of humaneness. Confucius' concept of humaneness (Chinese: 仁; pinyin: rén) is probably best expressed in the Confucian version of the Ethic of reciprocity, or the Golden Rule: "do not do unto others what you would not have them do unto you."

Confucius never stated whether man was born good or evil,[3] noting that 'By nature men are similar; by practice men are wide apart' [4] - implying that whether good or bad, Confucius must have perceived all men to be born with intrinsic similarities, but that man is conditioned and influenced by study and practise.

Rén also has a political dimension. If the ruler lacks rén, Confucianism holds, it will be difficult if not impossible for his subjects to behave humanely. Rén is the basis of Confucian political theory: it presupposes an autocratic ruler, exhorted to refrain from acting inhumanely towards his subjects. An inhumane ruler runs the risk of losing the "Mandate of Heaven", the right to rule. A ruler lacking such a mandate need not be obeyed. But a ruler who reigns humanely and takes care of the people is to be obeyed strictly, for the benevolence of his dominion shows that he has been mandated by heaven. Confucius himself had little to say on the will of the people, but his leading follower Mencius did state on one occasion that the people's opinion on certain weighty matters should be considered.

The gentleman

The term jūnzǐ (Chinese: 君子; lit. 'lord's child') is crucial to classical Confucianism. Confucianism exhorts all people to strive for the ideal of a "gentleman" or "perfect man". A succinct description of the "perfect man" is one who "combines the qualities of saint, scholar, and gentleman." In modern times the masculine translation in English is also traditional and is still frequently used. Elitism was bound up with the concept, and gentlemen were expected to act as moral guides to the rest of society.

They were to:

- cultivate themselves morally;

- show filial piety and loyalty where these are due;

- cultivate humanity, or benevolence.

The great exemplar of the perfect gentleman is Confucius himself. Perhaps the tragedy of his life was that he was never awarded the high official position which he desired, from which he wished to demonstrate the general well-being that would ensue if humane persons ruled and administered the state.

The opposite of the Jūnzǐ was the Xiǎorén (Chinese: 小人; pinyin: xiǎorén; lit. 'small person'). The character 小 in this context means petty in mind and heart, narrowly self-interested, greedy, superficial, or materialistic.

Rectification of names

Confucius believed that social disorder often stemmed from failure to perceive, understand, and deal with reality. Fundamentally, then, social disorder can stem from the failure to call things by their proper names, and his solution to this was Zhèngmíng (Chinese: [正名]; pinyin: zhèngmíng; lit. 'rectification of terms'). He gave an explanation of zhengming to one of his disciples.

Zi-lu said, "The ruler of Wei has been waiting for you, in order with you to administer the government. What will you consider the first thing to be done?"

The Master replied, "What is necessary is to rectify names."

"So! indeed!" said Zi-lu. "You are wide of the mark! Why must there be such rectification?"

The Master said, "How uncultivated you are, Yu! A superior man, in regard to what he does not know, shows a cautious reserve.

If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things.

If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success.

When affairs cannot be carried on to success, proprieties and music do not flourish.

When proprieties and music do not flourish, punishments will not be properly awarded.

When punishments are not properly awarded, the people do not know how to move hand or foot.

Therefore a superior man considers it necessary that the names he uses may be spoken appropriately, and also that what he speaks may be carried out appropriately. What the superior man requires is just that in his words there may be nothing incorrect."

(Analects XIII, 3, tr. Legge)

Xun Zi chapter (22) "On the Rectification of Names" claims the ancient sage-kings chose names (Chinese: [名]; pinyin: míng) that directly corresponded with actualities (Chinese: [實]; pinyin: shí), but later generations confused terminology, coined new nomenclature, and thus could no longer distinguish right from wrong.

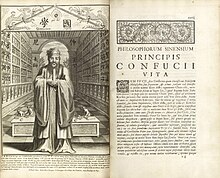

Influence in 17th Century Europe

The works of Confucius were translated into European languages through the agency of Jesuit scholars stationed in China.[5] Matteo Ricci started to report on the thoughts of Confucius, and father Prospero Intorcetta published the life and works of Confucius into Latin in 1687.[6] It is thought that such works had considerable importance[citation needed] on European thinkers[who?] of the period, particularly among the Deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Western civilization.[6][7]

Critique

Promotion of corruption

Like some other political philosophies, Confucianism is reluctant to employ laws. In a society where relationships are considered more important than the laws themselves, if no other power forces government officers to take the common interest into consideration, corruption and nepotism may arise. It has been suggested that a mix between Buddhism and Confucianism would be a perfect religion, with laws from Buddhism and logic from Confucianism[citation needed].

However, the above arguement is not the real point. Confucianism does not negate laws. Confucius' idea is indicated by his advice for Min Zijian (闵子骞) on political affairs: "By moral, by law" (以德以法). Actually, in traditional China, one of the main roles of regional officials was to practice law. In Confucian political philosophy, law is necessary, but statesmen should lay more importance on morals.

As lower-ranking government officers' salaries were often far lower than the minimum required to raise a family, while high-ranking officials (even though extremely rich and powerful) receive a salary of a value much lower than their self-perceived contribution (for example their incomes are often substantially less than a successful merchant), Chinese society was frequently affected by those problems. Even if some means to control and reduce corruption and nepotism have been successfully used in China, Confucianism is criticized for not providing such a means itself. But there's no theory in Confucianism suggesting paying higher-ranking officials excessively or paying lower-ranking officials on the level unable to raise a family. Salary of officials varies in different era, comparatively high in the Han Dynasty, and low in the Ming Dynasty even for high-ranking officials. There is a poem titled Bei Men (北門) in Shi Jing that voices the hard life of a low-ranking official, showing Confucius' sympathy.

Cyclical progress of moral

Another problem raised by Confucianism is that if children are always to listen and to respect parents and grandparents wishes(filial piety), then it would be hard for them to progress in what they want to think and believe in. This could also be a long term disadvantage as other nations progress both morally and perhaps economically ,supporters of Confucianism would keep life morally and perhaps even socially the same. Due to the fact that life is to remain the same by listening only to the wishes of your parents,etc. This could be a problem as then it could be called "backwards". However as progress is only to be in a cycle of parents listening to grandparents, children listening to parents, then it can't change.

Loss of free-will and individuality

Another similar critique of Confucianism is that if children are always to obey, respect and listen to their parents then it would not be up to the children to decide what they wish to do with their lives in the future but their parents. This is a loss of freedom for the young individual, of course one could argue that a young mind would not know what is best; parents would be acting in the best interests of the child. But by making the decision for him/her ,once he/she has decided to do something else that his/her parents had not planned or doesn't want him/her to do then it could already be too late or there could be an argument against the Confucian thinking of harmony and order of parents to children.

Female Equality then and now

In China, women were treated as second class citizens (for around 1500 years till the end of Qing), this was because Confucius thought that all wives should listen to their husbands and in doing so keep social harmony. This for a while was so extreme that some women weren't even given names nor did they go to school, they were expected to be in homes and take care of the family.

Nowadays, since the communists took the country in 1949, women have had the rights to attend school, get a job and overall have as much rights as a man in China. However social attitudes are still mostly the same as before and females are still treated as second class citizens in the family; parents still prefer to have a boy rather than a girl, perhaps worsened by the one child policy, as they are seen as the heir to the family and are able to continue the family's surname, plus they are viewed as better financial providers once the parents have retired. It also because that when the daughter of the family gets married they "in a sense" become a part of the groom's family. Examples of this is that their child will be born in the province/city where the groom's family comes from (if possible), plus the son/daughter will have the father's surname.

Religion or Philosophy debate

There is debate about the classification of Confucianism as a religion or a philosophy. Many attributes common among religions—such as ancestor worship, ritual, and sacrifice—apply to the practice of Confucianism; however, the religious features found in Confucian texts can be traced to non-Confucian Chinese belief. The position adopted by some is that Confucianism is a moral science or philosophy.[8] The problem clearly depends on how one defines religion. Since the 1970s scholars have attempted to assess the religious status of Confucianism without assuming a definition based on the Western model (for example, Frederick Streng's definition, "a means of ultimate transformation"[9]). Under such a definition Confucianism can legitimately be considered a religious tradition.[10]

Names for Confucianism

Several names for Confucianism exist in Chinese.

- "School of the scholars" (Chinese: 儒家; pinyin: Rújiā)

- "Teaching of the scholars" (Chinese: 儒教; pinyin: Rújiào)

- "Study of the scholars" (simplified Chinese: 儒学; traditional Chinese: 儒學; pinyin: Rúxué)

- "Teaching of Confucius" (Chinese: 孔教; pinyin: Kǒngjiào)

Three of these use the Chinese character? rú, meaning "scholar". These names do not use the name "Confucius" at all, but instead center on the figure or ideal of the Confucian scholar; however, the suffixes of jiā, jiào, and xué carry different implications as to the nature of Confucianism itself.

Rújiā contains the character jiā, which literally means "house" or "family". In this context, it is more readily construed as meaning "school of thought", since it is also used to construct the names of philosophical schools contemporary with Confucianism: for example, the Chinese names for Legalism and Mohism end in jiā.

Rújiào and Kǒngjiào contain the Chinese character jiào, the noun "teach", used in such as terms as "education", or "educator". The term, however, is notably used to construct the names of religions in Chinese: the terms for Islam, Judaism, Christianity, and other religions in Chinese all end with jiào.

Rúxué contains xué 'study'. The term is parallel to -ology in English, being used to construct the names of academic fields: the Chinese names of fields such as physics, chemistry, biology, political science, economics, and sociology all end in xué.

See also

- Wen Tianxiang

- Temple of Confucius

- Confucian view of marriage

- Confucianism in Indonesia

- Confucian art

- Boston Confucians

- Homosexuality and Confucianism

- Korean Confucianism

- Neo-Confucianism

- Neo-Confucianism in Japan

- New Confucianism

- Thirteen Classics

References

- ^ Levinson, David; Christensen, Karen "Encyclopedia of Modern Asia (2002) pg 157

- ^ Chinese Legal Theories

- ^ Homer H. Dubs: 'Nature in the Teaching of Confucius', p. 233

- ^ Lun Yu (Yang Huo) 13/05/2009

- ^ The first was Michele Ruggieri who had returned from China to Italy in 1588, and carried on translating in Latin Chinese classics, while residing in Salerno

- ^ a b "Windows into China", John Parker, p.25, ISBN 0890730504

- ^ The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation, John Hobson, p194-195, ISBN 0521547245

- ^ Centre for Confucian Science (Korea); Introduction to Confucianism

- ^ Streng, Frederick, "Understanding Religious Life," 3rd ed. (1985), p. 2

- ^ Taylor, Rodney L., "The Religious Dimensions of Confucianism" (1990); Tu Weiming and Mary Evelyn Tucker, eds., "Confucian Spirituality," 2 vols. (2003, 2004); Adler, Joseph A., "Confucianism as Religion / Religious Tradition / Neither: Still Hazy After All These Years" (2006)

Further reading

- Creel, Herrlee G. Confucius and the Chinese Way. Reprint. New York: Harper Torchbooks. (Originally published under the title Confucius—the Man and the Myth.)

- Fingarette, Herbert. Confucius: The Secular as Sacred ISBN 1-57766-010-2.

- Ivanhoe, Philip J. Confucian Moral Self Cultivation. 2nd rev. ed., Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

- Nivison, David S. The Ways of Confucianism. Chicago: Open Court Press.

- Max Weber, The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism.

- Yao, Xinzhong. (2000) An Introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Interfaith Online: Confucianism

- Confucian Documents at the Internet Sacred Texts Archive.

- Oriental Philosophy, "Topic:Confucianism"