Arch Oboler

Arch Oboler (December 7, 1907 – March 19, 1987) was a playwright, screenwriter, novelist, producer and director who was active in radio, films, theater and television.

He generated much attention with his radio scripts, particularly the horror series Lights Out, and his work in radio remains the outstanding period of his career. Praised as one of broadcasting's top talents, he is regarded today as a key innovator of radio drama. Old time radio expert John Dunning[1] wrote:

- Few people were ambivalent when it came to Arch Oboler. He was one of those intense personalities who are liked and disliked with equal fire.

Biography

He was born in Chicago, Illinois, to Leon Oboler and Clara Oboler, Jewish immigrants from Riga, Latvia.[2] Arch Oboler briefly attended the University of Chicago prior to dropping out to pursue a full-time writing career.

Radio

Oboler sold his first radio scripts while still in high school during the 1920s and rose to fame when he began scripting the NBC horror anthology Lights Out in 1936. He later found notoriety with his script contribution to the 12 December 1937 edition of The Chase and Sanborn Hour. In Oboler's sketch, host Don Ameche and guest Mae West portrayed a slightly bawdy Adam and Eve, satirizing the Biblical tale of the Garden of Eden. On the surface, the sketch did not feature much more than West's customary suggestive double-entendres, and today it seems quite tame. But in 1937, that sketch and a subsequent routine featuring West trading suggestive quips with Edgar Bergen's dummy Charlie McCarthy helped the broadcast cause a furor that resulted in West being banned from broadcasting and from being mentioned at all on NBC programming for 15 years. The timing may have been a contributing factor, according to radio historian Gerald S. Nachman in Raised on Radio:

- The sketch resulted in letters from outraged listeners and decency groups... What upset churchgoing listeners wasn't the Biblical parody so much as the fact that it had the bad luck to air on a Sunday show.[3]

When Oboler took over Lights Out in 1936, the show was already a sensation because of creator Wyllis Cooper's violent, quirky scripts, and Oboler continued in a similar vein, announcing during the opening of each episode:

- This is Arch Oboler bringing you another of our series of stories of the unusual, and once again we caution you: These Lights Out stories are definitely not for the timid soul. So we tell you calmly and very sincerely, if you frighten easily, turn off your radio now.

One of Oboler's best remembered scripts for Lights Out was Chicken Heart, first broadcast March 10, 1937:

- Dr. Calvin: I tell you that mass of flesh was a chicken heart... the tissue of which for some reason is undergoing constant, rapid, accelerating growth. With every passing hour its growth is doubling. Do you know what that means? If it is now one block in size, within 30 hours that cannibal flesh will have increased in size to one square block to the 30th power. In 30 hours every inch of this whole city will be crushed under that moving flesh. Within 60 hours it will have covered the entire state. Within two weeks the entire United States. You ask for the National Guard. I say call out the entire army. Blast this thing off the earth.[4][5]

Curiously, in the 1960s, "Chicken Heart" became more associated with comedian Bill Cosby than Oboler. Cosby's retelling of the radio drama with humorous vocalized sound effects became one of his most popular comedy routines, recorded on Cosby's Wonderfulness (1966) and available today on both YouTube and a CD reissue.

In 1939, Oboler introduced another series, Arch Oboler's Plays, on NBC. In addition to horror tales, the dramas on this series often employed more topical material, especially regarding early World War II events, and the cast featured many leading film actors. After a year on NBC, it returned for a short run on Mutual in 1945.[1] The series was syndicated in 1964.

Films

In making a leap from radio to film, Oboler was sometimes compared to Orson Welles, as in this commentary by Marty Baumann:

Even as Welles shocked much of the nation with the unforgettable War of the Worlds sham, so did Oboler incite panic with an episode detailing the horror of a giant, undulating chicken heart. The very fact that something patently silly could nonetheless be terrifying is a testament to Oboler's genius for manipulating his medium. Like Welles, Oboler was eventually summoned to Hollywood and began churning out feature scripts for mellers like RKO's Gangway for Tomorrow. Proving to producers that he knew his way around a screenplay, Arch was at last given the opportunity to direct. Forgotten features like Bewitched and The Arnelo Affair bore his unique dramatic stamp, but Oboler's seeming inability to coax warm performances from his actors dulled whatever edge his scripts possessed.[6]

His screen credits include Escape (1940) and On Our Merry Way (1948). By 1945, he moved into directing with Bewitched and Strange Holiday, followed by the post-apocalyptic Five (1951), filmed at his own Frank Lloyd Wright-designed house.

Oboler made film history with the 3-D effects in Bwana Devil (1952). The Twonky (1953) was adapted from the Lewis Padgett short story in the September, 1942, issue of Astounding Science Fiction. Oboler returned to films with another 3-D feature, The Bubble, in 1966.

Broadway

Sidney Lumet directed Oboler's Broadway play, Night of the Auk, a science fiction drama about astronauts returning to Earth after the first moon landing. The play was based on Oboler's radio play Rocket from Manhattan, which aired as part of Arch Oboler's Plays in September 1945.[7] Produced by Kermit Bloomgarden, the play ran for only eight performances in December 1956 despite a cast that included Martin Brooks, Wendell Corey, Christopher Plummer, Claude Rains and Dick York. In the December 17, 1956 issue, Time reviewed:

Night of the Auk (by Arch Oboler) took place on a rocket ship returning to the earth from man's first landing on the moon (time: "The day after some tomorrow"). The mood of the return voyage is far from jubilant, what with a loathed egomaniac in command, a succession of murders and suicides, the discovery that full-scale atomic war has broken out on earth, and the knowledge that the rocket ship itself is almost surely doomed. Playwright Oboler seems indeed to be prophesying that the atomic age may end up with man as extinct as the great auk. Closing at week's end, the play mingled one or two thrills with an appalling number of frills, one or two philosophic truths with a succession of Polonius-like truisms, an occasional feeling for language with pretentious and barbarous misuse of it. A good cast of actors, including Claude Rains, Christopher Plummer and Wendell Corey, were unhappily squandered on a pudding of a script — part scientific jargon, part Mermaid Tavern verse, part Madison Avenue prose — that sounded like cosmic advertising copy.[8]

Television

In 1949, Oboler helmed an anthology television series, Oboler's Comedy Theatre (aka Arch Oboler's Comedy Theater) which ran for six episodes from September to November. In the premiere show, "Ostrich in Bed," a couple awaiting the arrival of a dinner guest find an ostrich in their bedroom. In "Mr. Dydee" a dim-witted horse player inherits a diaper service.

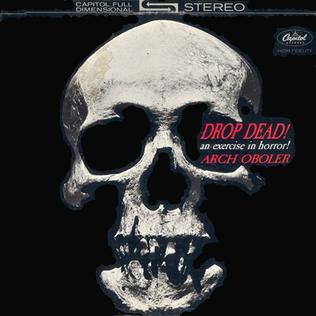

Recordings

Audio horror gained an added dimension with Oboler's stereo LP recording, Drop Dead! An Exercise in Horror (1962). It features the following tracks: "Introduction to Horror," "I'm Hungry," "Taking Papa Home," "The Dark," "A Day at the Dentist's," "The Posse," "Chicken Heart" and "The Laughing Man." The cast featured some well-known radio actors: Edgar Barrier, Bea Benaderet, Lawrence Dobkin, Sam Edwards, Virginia Gregg, Jerry Hausner, Jack Johnstone, Jack Kruschen, Forrest Lewis, Junius Matthews, Ralph Moody, Mercedes McCambridge, Harold Peary, Barney Phillips, Bill Phipps, Olan Soule and Chet Stratton.

Books

His work was collected in Free World Theatre: Nineteen New Radio Plays (Random House, 1944) and Oboler Omnibus: Radio Plays and Personalities (Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1945). Night of the Auk: A Free Prose Play was published by Horizon Press in 1958. His short story "And Adam Begot" was included in Julius Fast's Out of This World anthology (Penguin, 1944), and "Come to the Bank" was published in Weird Tales (Fall 1984).[9]

Oboler also wrote non-fiction, such as his "My Jackasses and the Fire" in the June 1960 issue of Coronet. His fantasy novel, House on Fire (Bartholomew House, 1969) was adapted by Oboler for radio's Mutual Radio Theater in 1980.

Personal life

Oboler married the fomer Eleanor Helfand; they were the parents of four sons: Guy Oboler, David Oboler, Steven Oboler, and Peter Oboler.[2] On April 7, 1958, Oboler's six-year-old son, Peter, drowned in rainwater collected in excavations at Oboler's Malibu home.[10] The house was designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright; the Wright-designed Oboler residential complex is named Eaglefeather. The house is featured in Obler's film Five. Arch Oboler died in Westlake Village, California in 1987.

References

- ^ a b Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. Oxford University Press. pp. 37–39. ISBN 0-19-507678-8.

- ^ a b Family Tree Maker

- ^ Nachman, Gerald. Raised on Radio. Pantheon, 1998.

- ^ Lights Out "Chicken Heart"

- ^ Jerry Haendiges Vintage Radio Logs: Lights Out

- ^ Baumann, Marty. The Astounding B Monster Archive: "Arch Oboler: Radio raconteur enters new dimension".

- ^ Lucanio, Patrick; Coville, Gary (2002). Smokin’ Rockets: The Romance of Technology in American Film, Radio and Television, 1945-1962. pp. 66–78. ISBN 0-7864-1233-X.

- ^ Time, December 17, 1956.

- ^ Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- ^ "Son of Arch Oboler Drowns in Excavation," Cumberland Evening Times, April 8, 1958.