Rickettsia

| Rickettsia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Rickettsia rickettsii | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | Alpha Proteobacteria

|

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Rickettsia da Rocha-Lima, 1916

|

| Species | |

|

Rickettsia felis | |

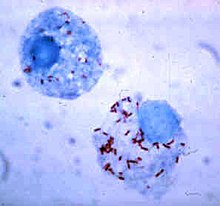

Rickettsia is a genus of motile, Gram-negative, non-sporeforming, highly pleomorphic bacteria that can present as cocci (0.1 μm in diameter), rods (1–4 μm long) or thread-like (10 μm long). Obligate intracellular parasites, the Rickettsia survival depends on entry, growth, and replication within the cytoplasm of eukaryotic host cells (typically endothelial cells).[1] Because of this, Rickettsia cannot live in artificial nutrient environments and are grown either in tissue or embryo cultures (typically, chicken embryos are used). In the past they were regarded as microorganisms positioned somewhere between viruses and true bacteria. The majority of Rickettsia bacteria are susceptible to antibiotics of the tetracycline group.

Rickettsia species are carried as parasites by many ticks, fleas, and lice, and cause diseases such as typhus, rickettsialpox, Boutonneuse fever, African tick bite fever, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Australian Tick Typhus, Flinders Island Spotted Fever and Queensland tick typhus [2] in human beings. They have also been associated with a range of plant diseases. Like viruses, they only grow inside living cells. The name rickettsia is often used for any member of the Rickettsiales. They are thought to be the closest living relatives to bacteria that were the origin of the mitochondria organelle that exists inside most eukaryotic cells.

The method of growing Rickettsia in chicken embryos was invented by Ernest William Goodpasture and his colleagues at Vanderbilt University in the early 1930s.

Classification

The classification of Rickettsia into three groups (spotted fever, typhus and scrub typhus) was based on serology. This grouping has since been confirmed by DNA sequencing. All three of these contain human pathogens. The scrub typhus group has been reclassified as a new genus – Orientia – but many medical textbooks still list this group under the ricketsial diseases.

However more recently it has become apparent that rickettsia are more widespread than previously believed and are known to be associated with arthropods, leeches and protists. Divisions have also been identified in the spotted fever group and it has been suggested that this should be divided into two clades.[3] The arthropod species appear to be ancestral to the vertebrate species and the species infecting leeches and protists are unrelated.[4]

Spotted fever group

- R. rickettsii (Western hemisphere)

- R. akari (USA, former Soviet Union)

- R. conorii (Mediterranean countries, Africa, Southwest Asia, India)

- R. siberica (Siberia, Mongolia, northern China)

- Siberian tick typhus

- R. australis (Australia)

- R. japonica (Japan)

- Oriental spotted fever

- R. africae (South Africa)

- African Tick Bite Fever

Typhus group

- R. prowazekii (Worldwide)

- Epidemic, recrudescent and sporadic typhus

- R. typhi (Worldwide)

- Murine (endemic) typhus

Scrub typhus group

- The causative agent of scrub typhus formerly known as R. tsutsugamushi has been reclassified into the genus Orientia.

Flora and fauna pathogenesis

The following plant diseases have been associated with Rickettsia-like organisms[5].

- Beet latent Rosette RLO

- Citrus Greening bacterium

- Clover leaf RLO

- Grapevine infectious necrosis RLO

- Grapevine Pierce's RLO

- Grapevine yellos RLO

- Larch witch's broom disease

- Peach phony RLO

Infection occurs in non-human mammals; for example, species of Rickettsia have been found to afflict the South Amercian Guanaco, Lama guanacoe.[6]

Genomics

Certain segments of Rickettsial genomes resemble that of mitochondria.[7] The deciphered genome of R. prowazekii is 1,111,523 bp long and contains 834 protein-coding genes.[8] Unlike free-living bacteria, it contains no genes for anaerobic glycolysis or genes involved in the biosynthesis and regulation of amino acids and nucleosides. In this regard it is similar to mitochondrial genomes; in both cases, nuclear (host) resources are used. ATP production in Rickettsia is the same as that in mitochondria. In fact, of all the microbes known, the Rickettsia is probably the closest "relative" (in phylogenetic sense) to the mitochondria. Unlike the latter, the genome of R. prowazekii, however, contains a complete set of genes encoding for the tricarboxylic acid cycle and the respiratory chain complex. Still, the genomes of the Rickettsia as well as the mitochondria are frequently said to be "small, highly derived products of several types of reductive evolution".

The recent discovery of another parallel between Rickettsia and viruses may become a basis for fighting HIV infection.[9] Human immune response to the scrub typhus pathogen, Orientia tsutsugamushi rickettsia, appears to provide a beneficial effect against HIV infection progress, negatively influencing the virus replication process. A probable reason for this actively studied phenomenon is a certain degree of homology between the rickettsia and the virus – namely, common epitope(s) due to common genome fragment(s) in both pathogens. Surprisingly, the other infection reported to be likely to provide the same effect (decrease in viral load) is the virus-caused illness dengue fever.

Naming

The genus Rickettsia is named after Howard Taylor Ricketts (1871–1910), who studied Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the Bitterroot Valley of Montana, and eventually died of typhus after studying that disease in Mexico City. Despite the similar name, Rickettsia bacteria do not cause rickets, which is a result of vitamin D deficiency.

References

- ^ Walker DH (1996). Rickettsiae. In: Barron's Medical Microbiology (Barron S et al., eds.) (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. (via NCBI Bookshelf) ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ^ Unsworth NB, Stenos J, Graves SR; et al. (2007). "Flinders Island spotted fever rickettsioses caused by "marmionii" strain of Rickettsia honei, Eastern Australia". Emerging infectious diseases. 13 (4): 566–73. doi:10.3201/eid1304.060087. PMID 17553271.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gillespie J.J., Beier M.S., Rahman M.S., Ammerman N.C., Shallom J.M., Purkayastha A., Sobral B.S., Azad A.F. Plasmids and rickettsial evolution: insight from 'Rickettsia felis'. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000266.

- ^ Perlman S.J., Hunter M.S., Zchori-Fein E. The emerging diversity of 'Rickettsia'. Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences. 2006;273:2097–2106. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3541

- ^ Smith IM, Dunez J, Lelliot RA, Phillips DH, Archer SA (1988). European Handbook of Plant Diseases. Blackwell Scientific Publications. ISBN 0-632-01222-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ C. Michael Hogan. 2008. Guanaco: Lama guanicoe, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Strömberg

- ^ Emelyanov VV (2003). "Mitochondrial connection to the origin of the eukaryotic cell". Eur J Biochem. 270 (8): 1599–618. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03499.x. PMID 12694174.

- ^ Andersson SG; et al. (1998). "The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria". Nature. 396 (6707): 133–40. doi:10.1038/24094. PMID 9823893.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Kannangara S, DeSimone JA, Pomerantz RJ (2005). "Attenuation of HIV-1 infection by other microbial agents". J Infect Dis. 192 (6): 1003–9. doi:10.1086/432767. PMID 16107952.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Rickettsia (from PATRIC the PathoSystems Resource Integration Center, a NIAID Bioinformatics Resource Center)

- African Tick Bite Fever from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Rickettsia Infection - Disease.com