Masaccio

Masaccio | |

|---|---|

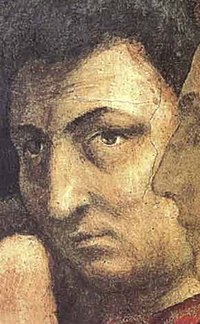

Detail of St. Peter Raising the Son of Theophilus and St. Peter Enthroned as First Bishop of Antioch, Brancacci Chapel, S. Maria del Carmine, Florence | |

| Born | Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Mone (Simone) Cassai |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting, Fresco |

| Notable work | Brancacci Chapel (The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, ''The Tribute Money'') c. 1425 Pisa Altarpiece 1426 Holy Trinity c. 1427 |

| Movement | Early Renaissance |

| Patron(s) | Felice de Michele Brancacci ser Giuliano di Colino degli Scarsi da San Giusto |

Masaccio (born Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone; December 21, 1401 – autumn 1428), was the first great painter of the Quattrocento period of the Italian Renaissance. According to Vasari, Masaccio was the best painter of his generation because of his skill at recreating lifelike figures and movements as well as a convincing sense of three-dimensionality.[1]

The name Masaccio is a humorous version of Maso (short for Tommaso), meaning "big", "fat", "clumsy" or "messy" Tom. The name may have been created to distinguish him from his principal collaborator, also called Maso, who came to be known as Masolino ("little/delicate Tom").

Despite his brief career, he had a profound influence on other artists. He was one of the first to use Linear perspective in his painting, employing techniques such as vanishing point in art for the first time. He also moved away from the International Gothic style and elaborate ornamentation of artists like Gentile da Fabriano to a more naturalistic mode that employed perspective and chiaroscuro for greater realism.

Biography

Early life

Masaccio was born to Giovanni di Simone Cassai and Jacopa di Martinozzo in Castel San Giovanni di Altura, now San Giovanni Valdarno (today part of the province of Arezzo, Tuscany).[2] His father was a notary and his mother the daughter of an innkeeper of Barberino di Mugello, a town a few miles south of Florence. His family name, Cassai, comes from the trade of his paternal grandfather Simone and granduncle Lorenzo, who were carpenters - cabinet makers ("casse", hence "cassai"). His father died in 1406, when Tommaso was only five; in that year another brother was born, called Giovanni (1406-1486) after the dead father. He also was to become a painter, with the nickname of lo Scheggia meaning "the splinter." [3] Monna Jacopa later married an elderly apothecary, Tedesco di Maestro Feo, who already had several daughters, one of whom grew up to marry the only other documented painter from Castel San Giovanni, Mariotto di Cristofano (1393-1457).

There is no evidence for Masaccio's artistic education.[4] Renaissance painters traditionally began an apprenticeship with an established master at about the age of 12; Masaccio would likely have had to move to Florence to receive his training, but he was not documented in the city until he joined the painters guild (the Arte de' Medici e Speziali) as an independent master on January 7, 1422, signing as "Masus S. Johannis Simonis pictor populi S. Nicholae de Florentia."

First works

The first works attributed to Masaccio are the Cascia Altarpiece, (1422), which depicts the Madonna enthroned with angels and saints, and a Virgin and Child with St. Anne, (c. 1424) at the Uffizi: they were already works of very high quality. The second work was a collaboration with an older and already renowned artist, Masolino da Panicale.

Maturity

In Florence, Masaccio could study the works of Giotto and become friends with Alberti, Brunelleschi and Donatello. According to Vasari, at their prompting in 1423 Masaccio travelled to Rome with Masolino: from that point he was freed of all Gothic and Byzantine influence, as may be seen in his altarpiece for the Carmelite Church in Pisa, the central panel of which (The Madonna and the Child) is now in the National Gallery, London. As well as a sculptural and human Madonna the work features a convincing perspectival depiction of her throne. The traces of influences from ancient Roman and Greek art that are present in some of Masaccio's works presumably originated from this trip: they should also have been present in a lost Sagra, (today known through some drawings, including one by Michelangelo), a fresco commissioned for the consecration ceremony of the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence (April 19, 1422). It was destroyed when the church's cloister was rebuilt at the end of the 16th century.

Brancacci chapel

In 1424 the "duo preciso e noto" ("well and known duo") of Masaccio and Masolino was commissioned by the powerful and rich Felice Brancacci to execute a cycle of frescoes for the Brancacci Chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. The theme of the frescoes in the little chapel was to be the "Histories of St. Peter". The genius of Masaccio shows clearly in these frescoes. In the "Resurrection of the Son of Theophilus", he painted a pavement in perspective, framed by large buildings to obtain a depth of field and three-dimensional space in which the figures are placed proportionate to their surroundings. In this he was a pioneer in applying the newly discovered rules of perspective.

Masaccio's scenes show his reference to Giotto especially. The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, depicting a distressed Adam and Eve nude, had a huge influence on Michelangelo. Another major work is The Tribute Money in which Jesus and the Apostles are depicted as neo-classical archetypes. Seldom noted is that the shadows of the figures all fall away from the chapel window, as if the figures are lit by it; this an added stroke of verisimilitude and further tribute to Masaccio's innovative genius.

On September 1425 Masolino left the work and went to Hungary. It is not known if this was because of money quarrels with Felice or even if there was an artistic divergence with Masaccio. It has also been supposed that Masolino planned this trip from the very beginning, and needed a close collaborator who could continue the work after his departure.

Some of the scenes completed by the duo were lost in a fire in 1771; we know about them only through Vasari's biography. The surviving parts were extensively blackened by smoke, and the recent removal of marble slabs covering two areas of the paintings has revealed the original appearance of the work. Masaccio left the frescoes unfinished in 1426 in order to respond to other commissions, probably coming from the same patron. However, it has also been suggested that the declining finances of Felice Brancacci were insufficient to pay for any more work, so the painter therefore sought work elsewhere.

Masaccio returned in 1427 to work again in the Carmine, beginning the Resurrection of the Son of Theophilus, but apparently left it, too, unfinished, though it has also been suggested that the painting was severely damaged later in the century because it contained portraits of the Brancacci family, at that time excoriated as enemies of the Medici. This painting was either restored or completed more than fifty years later by Filippino Lippi.

Other works

On February 19, 1426 Masaccio was commissioned by Giuliano di Colino degli Scarsi, for the sum of 80 florins, to paint a major altarpiece, the Pisa Polyptych, for his chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Pisa. The work was dismantled and dispersed in the 18th century, and only eleven of about twenty original panels have been rediscovered in various places in the world. Masaccio probably worked on it entirely in Pisa, shuttling back and forth to Florence, where he was still working on the Histories of St. Peter. In these years Donatello was also working in Pisa at a monument for Cardinal Rinaldo Brancacci, to be sent to Naples. It has been suggested that Masaccio's first ventures in plasticity and perspective were based on Donatello's sculpture, before he could study Brunelleschi's more scientific approach to perspective.

Through the help of Brunelleschi, in 1427 Masaccio won a prestigious commission to produce a Holy Trinity for the Santa Maria Novella church in Florence. The fresco, considered by many his masterwork, marks the first use of systematic linear perspective, possibly devised by Masaccio with the assistance of Brunelleschi himself. [[Image:Masaccio trinity.jp g|thumb|left|Holy Trinity, in full: "Trinity with the Virgin, Saint John the Evangelist, and Donors" (c. 1427) - Fresco, Santa Maria Novella, Florence]]

Masaccio produced two other works, a Nativity and an Annunciation, now lost, before leaving for Rome, where his companion Masolino was frescoing the Basilica di San Clemente. It has never been confirmed that Masaccio collaborated on that work, even though it is possible that he contributed to Masolino's polyptych of the altar of St. Mary Major with his panel portraying St. Jerome and St. John the Baptist, now in the National Gallery of London. Masaccio died at the end of 1428. According to a legend, he was poisoned by a jealous rival painter.

Only four frescoes undoubtedly from Masaccio's hand still exist today, although many other works have been at least partially attributed to him. Others are believed to have been destroyed.

Legacy

Masaccio profoundly influenced the art of painting in the Renaissance. According to Vasari, all Florentine painters studied his frescoes extensively in order to "learn the precepts and rules for painting well". He transformed the direction of Italian painting, moving it away from the idealizations of Gothic art, and, for the first time, presenting it as part of a more profound, natural, and humanist world.

See also

Main works

- Crucifixion (c. 1426) - oil on table, 83 x 63 cm, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples

- Cascia Altarpiece (1422, dubious) oil on table, 108 x 153 cm, Cascia di Reggello

- The Tribute Money (1424-1428) - fresco, 247 x 597 cm, Brancacci Chapel, Florence

- Madonna with Child and St. Anne (1424-1425) - tempera on panel, 175 x 103 cm, Uffizi, Florence

- Madonna with Child (1424) - tempera on panel, 24 x 18 cm, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence

- Portrait of a Young Man (1425) - wood, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- St. Paul (1426) - tempera on wood, 51 x 30 cm, Museo Nazionale, Pisa

- Holy Trinity (1425-1428) - fresco, 667 x 317 cm, Santa Maria Novella, Florence

- Madonna with Child and Angel (1426) - oil on table, National Gallery, London

- Nativity (Berlin Tondo) (1427-1428) - tempera on wood, diameter 56 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin

- St. Jerome and St. John the Baptist (c. 1426-1428) panel, 114 x 55 cm, National Gallery, London

- St Andrew - oil on table, 51 x 31 cm, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Notes

- ^ Giorgio Vasari, Le Vite de' piu eccellenti pittori, scultori ed architettori, ed. Gaetano Milanesi, Florence, 1906, II, 287-288.

- ^ For English overviews of Masaccio's life and works, with references to the primary and secondary sources, see John T. Spike, Masaccio, New York: 1996, 21-64, and Diane Cole Ahl, The Cambridge Companion to Masaccio, Cambridge, 2002, 3-5.

- ^ On Giovanni's career, see Luciano Bellosi and Margaret Haines, Lo Scheggia, Florence, 1999.

- ^ Vasari (II, 295) identifies Masolino as Masaccio's teacher, but modern scholars have found that Masolino enrolled in the painters guild later than Masaccio and so could not have been his master. Scholars cannot agree on any teacher for the young artist, however.

- ^ Mack, p.66

References

- Mack, Rosamond E. Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian Art, 1300-1600, University of California Press, 2001 ISBN 0520221311