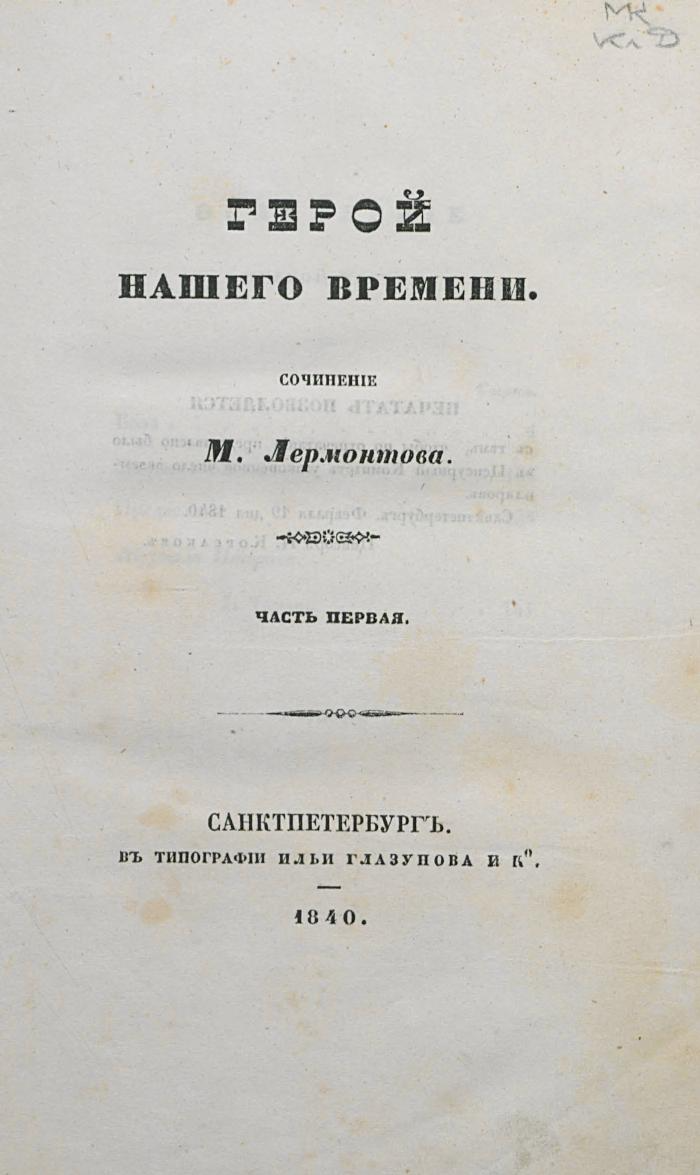

A Hero of Our Time

| |

| Author | Mikhail Lermontov |

|---|---|

| Original title | Герой нашего времени |

| Language | Russian |

| Publisher | Илья Глазунов и К. (Ilya Glazunov and K.) |

Publication date | 1840 |

| Publication place | Russia |

A Hero of Our Time (Russian: Герой нашего времени) is a short novel by Mikhail Lermontov, written in 1839 and revised in 1841. It is an example of the superfluous man novel, noted for its compelling Byronic hero (or anti-hero) Pechorin and for the beautiful descriptions of the Caucasus. There are several English translations, including one by Vladimir Nabokov in 1958.

Plot Structure

The book is divided into five short stories or novellas, plus (in the second edition) an authorial preface. There are three major narrators: an unnamed young travel writer who has received Pechorin's diaries after his death and who is implied to be Lermontov himself; Maxim Maximytch, an old staff-captain who served with Pechorin for some time during the Caucasian War; and Pechorin himself via his diaries. The stories depict Pechorin as impulsive, emotionally distant and manipulative, capable of extreme bravery but generally bored by his life.

In the longest novella, Princess Mary, Pechorin flirts with the Princess of the title, while conducting an affair with his ex-lover Vera, and kills his friend Grushnitsky (of whom he is secretly contemptuous) in a duel in which the participants stand in turn on the edge of a cliff so that the loser's death can be explained as an accidental fall. Eventually he rejects one woman only to be abandoned by the other.* Claude Sautet's film A Heart in Winter (Un Coeur en Hiver) was based on "his memories of" the Princess Mary section. [1]

The preface explains the author's idea of his character: "A Hero of Our Time, my dear readers, is indeed a portrait, but not of one man. It is a portrait built up of all our generation's vices in full bloom. You will again tell me that a human being cannot be so wicked, and I will reply that if you can believe in the existence of all the villains of tragedy and romance, why wouldn't believe that there was a Pechorin? If you could admire far more terrifying and repulsive types, why aren't you more merciful to this character, even if it is fictitious? Isn't it because there's more truth in it than you might wish?"

Grigoriy Aleksandrovich Pechorin

Pechorin is the embodiment of the Byronic hero. Byron’s works were of international repute and Lermontov mentions his name several times throughout the novel. According to the Byronic tradition, Pechorin is a character of contradiction. He is both sensitive and cynical. He is possessed of extreme arrogance, yet has a deep insight into his own character and epitomizes the melancholy of the romantic hero who broods on the futility of existence and the certainty of death. Pechorin’s whole philosophy concerning existence is oriented towards the nihilistic, creating in him somewhat of a distanced, alienated personality.* The name Pechorin is drawn from that of the Pechora River, in the far north, as a homage to Aleksandr Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, named after the Onega River.[1]

Pechorin, like Byron, treats women as an incentive for endless conquests and does not consider them worthy of any particular respect. He considers women such as Princess Mary to be little more than pawns in his games of romantic conquest, which in effect hold no meaning in his listless pursuit of pleasure. This is shown in his comment on Princess Mary: “I often wonder why I’m trying so hard to win the love of a girl I have no desire to seduce and whom I’d never marry.”

The only contradiction in Pechorin’s attitude to women are his genuine feelings for Vera, who loves him despite, and perhaps due to, all his faults. At the end of “Princess Mary” one is presented with a moment of hope as Pechorin gallops after Vera. The reader almost assumes that a meaning to his existence may be attained and that Pechorin can finally realize that true feelings are possible. Yet a lifetime of superficiality and cynicism cannot be so easily eradicated and when fate intervenes and Pechorin’s horse collapses, he undertakes no further effort to reach his one hope of redemption: “I saw how futile and senseless it was to pursue lost happiness. What more did I want? To see her again? For what?”

Pechorin's chronologically last adventure, was first described in the book, showing the events that explain his upcoming fall into depression and retreat from society, resulting in his self-predicted death. The narrator is Maxim Maximytch telling the story of a beautiful Circassian princess 'Bela', whom Pechorin abducts from her family and claims as his own. Maxim describes Pechorin's exemplary persistence to convince Bela to sexually give herself to him, in which she with time reciprocates. After living with Bela for some time, Pechorin starts explicating his need for freedom, which Bela starts noticing, fearing he might leave her. Though Bela is completely devoted to Pechorin, she says she's not his slave, rather a daughter of a prince, also showing the intention of leaving if he 'doesn't love her'. Maxim's sympathy for Bela makes him question Pechorin's intentions. Pechorin admits he loves her and is ready to die for her, but 'he has a restless fancy and insatiable heart, and that his life is emptier day by day'. He thinks his only remedy is to travel, to keep his spirit alive.

However Pechorin's behavior soon changes after Bela gets kidnapped by his enemy Kazbich, and becomes mortally wounded. After 2 days of suffering in delirium Bela spoke of her inner fears and her feelings for Pechorin, who listened without once leaving her side. After her death, Pechorin becomes physically ill, loses weight and becomes unsociable. After meeting with Maxim again, he acts coldly and antisocial, explicating deep depression and disinterest in interaction. He soon dies on his way back from Persia, admitting before that he is sure to never return.

Pechorin described his own personality as self-destructive, admitting he himself doesn't understand his purpose in the world of men. His boredom with life, feeling of emptiness, forces him to indulge in all possible pleasures and experiences, which soon, cause the downfall of those closest to him. He starts to realize this with Vera and Grushnitsky, while the tragedy with Bela soon leads to his complete emotional collapse.

His crushed spirit after this and after the duel with Grushnitsky can be interpreted that he is not the detached character that he makes himself out to be. Rather, it shows that he suffers from his actions. Yet many of his actions are described both by himself and appear to the reader to be arbitrary. Yet this is strange as Pechorin's intelligence is very high (typical of a byronic hero). Pechorin's explanation as to why his actions are arbitrary can be found in the last chapter where he speculates about fate. He sees his arbitrary behaviour not as being a subconscious reflex to past moments in his life but rather as fate. Pechorin grows dissatisfied with his life as each of his arbitrary actions lead him through more emotional suffering which he represses from the view of others.

Quotations

- My whole life has been merely a succession of miserable and unsuccessful denials of feelings or reason.

- ...I am not capable of close friendship: of two close friends, one is always the slave of the other, although frequently neither of them will admit it. I cannot be a slave, and to command in such circumstances is a tiresome business, because one must deceive at the same time.

- Afraid of decision, I buried my finer feelings in the depths of my heart and they died there.

- It is difficult to convince women of something; one must lead them to believe that they have convinced themselves.

- What of it? If I die, I die. It will be no great loss to the world, and I am thoroughly bored with life. I am like a man yawning at a ball; the only reason he does not go home to bed is that his carriage has not arrived yet.

- When I think of imminent and possible death, I think only of myself; some do not even do that. Friends, who will forget me tomorrow, or, worse still, who will weave God knows what fantastic yarns about me; and women, who in the embrace of another man will laugh at me in order that he might not be jealous of the departed--what do I care for them?

- Women! Women! Who will understand them? Their smiles contradict their glances, their words promise and lure, while the sound of their voices drives us away. One minute they comprehend and divine our most secret thoughts, and the next, they do not understand the clearest hints.

- There are two men within me - one lives in the full sense of the word, the other reflects and judges him. In an hour's time the first may be leaving you and the world for ever, and the second? ... the second? ...

- To cause another person suffering or joy, having no right to so-- isn't that the sweetest food of our pride? What is happiness but gratified pride?

- I'll hazard my life, even my honor, twenty times, but I will not sell my freedom. Why do I value it so much? What am I preparing myself for? What do I expect from the future? in fact, nothing at all.

- Grushnitski (to Pechorin): "Mon cher, je haïs les hommes pour ne pas les mépriser car autrement la vie serait une farce trop dégoûtante." ("My friend, I hate people to avoid despising them because otherwise, life would become too disgusting a farce.")

- Pechorin (replying to Grushnitski): "Mon cher, je méprise les femmes pour ne pas les aimer car autrement la vie serait un mélodrame trop ridicule" ("My friend, I despise women to avoid loving them because otherwise, life would become too ridiculous a melodrama.")

- "Passions are merely ideas in their initial stage."

See also

References

- ^ Murray, Christopher (2004). Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760-1850. New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 498. ISBN 1579584233.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)