Donner Party

The Donner Party (also called the Reed-Donner Party) was a group of 87 American pioneers who set off in a wagon train from Missouri to California in 1846, a journey that usually took about four months. Delayed by their choice to follow the untried Hastings Cutoff, the group became trapped by snow in the Sierra Nevada mountains; some resorted to cannibalism to survive, eating those who had succumbed to starvation and sickness. Lansford Hastings had promoted the route that bears his name as a shortcut to California, despite having never traveled it himself. The winding route through the Wasatch Mountains and Great Salt Lake Desert resulted in the loss of many of the party's cattle and wagons, and fragmentation of the group into bitter factions.

The pioneers were a month and a half behind schedule when they reached Truckee Lake in the Sierra Nevadas and were trapped by an unusually heavy snowfall. Their food stores ran out and members of the party set out on foot to obtain help. Family members in California made several rescue attempts, but the first relief party did not reach the stranded group until the middle of February 1847. Of the 87 members of the party, 45 survived the trip to California; males aged between 20 and 39 suffered the highest mortality rate, and females fared proportionally better than males.

Western immigration decreased significantly after news of the Donner Party's fate spread, until gold was discovered in California in 1848. The episode has endured in United States (U.S.) history as a tragic event during which the pioneers resorted to cannibalism. Historians have described it as "one of the most thrilling, heart-rending tragedies in California history",[1] explaining continued interest in the story because "the disaster was the most spectacular in the record of western migration".[2]

Background

The 1840s in the United States saw a dramatic increase of pioneers: people who left their homes in the east to settle in Oregon and California. Some, like Patrick Breen, saw California as a place where they would be free to live in a fully Catholic culture,[3] but many were inspired by the idea of Manifest Destiny, a philosophy that asserted the land between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans belonged to Americans and they should settle it.[4] The west of North America had been settled by the Spanish and Mexicans; Mexico governed California and disputed American claims to parts of the continent east of the Continental Divide. In late spring 1846, the two countries declared war, leaving American emigrants uncertain what to expect upon their arrival in California.[5]

The journey to the west took about four months for most emigrants.[6] Most wagon trains followed the same route west from Independence, Missouri to the Continental Divide. The main trail, which had acquired permanent ruts in the ground, allowed a wagon train to progress 15 miles (24 km) a day.[7] Because travelers needed a steady supply of water, wood, and fodder for the animals, the trail generally followed rivers to South Pass, a mountain pass relatively easy for wagons to negotiate.[8] After crossing South Pass, wagon trains could choose which route to take to their intended destination.[9] The trail to California took a winding route northwest to Fort Hall, before turning south.[10]

An early emigrant named Lansford W. Hastings had gone to California in 1842 and saw the promise of the undeveloped country. To entice settlers to an empire he envisioned himself at the head of, he published a guide for pioneers titled The Emigrants' Guide to Oregon and California.[11] In this book, he described a direct route across the Great Basin, which would bring emigrants through the Wasatch Mountains and across the Great Salt Lake Desert. As of 1846, only two men, including Hastings, were documented to have crossed the southern portion of this desert, and neither had been accompanied by wagons.[12][note 1] At the time of the book's publication, Hastings had not traveled any portion of the route; he remedied this in early 1846, when he journeyed from California to a scant supply station, run by Jim Bridger and a partner named Vasquez, located in Blacks Fork, Wyoming, trying to persuade travelers to turn south on this route.[11]

For emigrants to California, the most difficult part of the trail was the last 100 miles (160 km), crossing the Sierra Nevada Mountains with their wagons. This mountain range comprises 500 distinct peaks over 12,000 feet (3,700 m) high,[13] and the eastern side of the range is extremely steep, making it difficult for oxen to pull the wagons upward. Their height and proximity to the Pacific Ocean mean the Sierras receive more snow than most other mountain ranges in North America.[14] Timing was crucial to ensure that after leaving the civilization of Missouri to cross the vast wilderness to Oregon or California, wagon trains would not be bogged down by mud created by spring rains, or massive snowdrifts in the mountains from September onwards, and their horses and oxen would have enough spring grass to eat.[15]

Families and progress

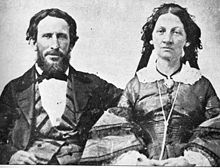

In the spring of 1846, over 500 wagons headed west from Independence.[16] Leaving on May 12, at the rear of the train,[17] was a group of 9 wagons, containing 32 members of the Reed and Donner families and their employees.[18] George Donner (1785–1847) was originally from North Carolina, but had settled in several places, gradually moving west to Kentucky, Indiana, and Texas. In the spring of 1846, he was a 62-year-old farmer in Springfield, Illinois. Donner brought his 44-year-old wife Tamsen and five daughters ranging in age from three to thirteen years old. Donner's older brother Jacob also joined, along with his wife, two teenage stepsons, and five children, the eldest of whom was nine.[19]

James F. Reed (1800–1874) was an Irish immigrant who settled in Illinois in 1831. He carried with him wife Margaret, daughters Patty and Virginia, sons James and Thomas, and mother-in-law Sarah Keyes, who was 75 years old,[note 2] and in the advanced stages of tuberculosis.[20] The Reeds hoped that the climate in the West would help Margaret, who had long been sickly.[21] Reed had amassed considerable wealth in Illinois from his furniture factory, sawmill, and work as a railroad contractor.[20] He built an ornate, custom-made, and unusually large wagon for his family, and was accompanied by several young men hired to drive the oxen, along with a hired girl.[21]

Within a week of their departure from Independence, the Reeds and Donners caught up with, and joined, a group of 50 wagons nominally led by William H. Russell.[17] On May 28, Margaret Reed's mother, Sarah Keyes, died from her illness; she was buried by the side of the trail.[22] By June 16, the company had traveled 450 miles (720 km), with 200 miles (320 km) to go before Fort Laramie, Wyoming. They had been delayed a few times by rain and a rising river, but Tamsen Donner wrote to a friend in Springfield, "indeed, if I do not experience something far worse than I have yet done, I shall say the trouble is all in getting started."[23][note 3] Young Virginia Reed recalled years later that during the first part of the trip she was "perfectly happy".[24]

Several other families joined the wagon train at various points along the way. Levinah Murphy was a widow with seven children, two of whom were grown and married and five of whom were adolescents. The Murphys with their spouses numbered thirteen in all. The Eddy family was headed by a young man with a wife and small child. Patrick Breen brought along his wife Peggy and seven children, all but the youngest of whom were boys. A 40-year-old bachelor named Patrick Dolan camped with the Breens, and a general animal handler named Antonio also came along.[25][26] The party's numbers swelled and shrank at each stop. Lewis Keseberg, a German immigrant, joined with his wife and daughter; a son was born on the trail.[27] Another German couple, the Wolfingers, were rumored to be wealthy. Two young single men named Spitzer and Reinhardt traveled with the Wolfingers, who also had a hired driver, "Dutch Charley" Burger. An older man named Hardkoop rode with them. Luke Halloran, a young man who seemed to be getting sicker with tuberculosis every day, was passed from family to family, as none of them could really spare the time and resources to care for him.[28]

When the party reached the Little Sandy River in Wyoming on July 20, a small group decided to find out more about the Hastings Cutoff.[29] Hastings had written letters to emigrants on the trails, notifying those on their way to California of his proposed route. On July 12, the Reeds and Donners were delivered a letter from Hastings by a runner on horseback.[30] In his letter, Hastings warned the emigrants that they could expect some opposition from the Mexican authorities in California, and he advised them therefore to band together in large groups. He also claimed to have "worked out a new and better road to California", and said he would be waiting at Fort Bridger to guide the emigrants along the new cutoff.[31]

The larger wagon train opted to follow the trail to Fort Hall, while the smaller group stopped to elect a leader and head to Bridger's supply station. Donner's peaceful, charitable nature, the fact that he was American, and his age, implying wisdom and experience, made him the group's first choice.[32] The other males in the group were European immigrants, young, and for various reasons, not considered to be ideal leaders, except for James Reed. Donner and Reed were friendly and respectful of each other, but where Donner was charitable, Reed seemed aristocratic and ostentatious with his wealth to the other members of the party. He was an immigrant as well, but had been living in the U.S. for a considerable time and had military experience. Reed was quick to make decisions, sometimes not taking into account others' opinions, making him seem imperious. He had already alienated one of the members of the wagon train with his ways.[33]

A journalist named Edwin Bryant had been traveling with the Russell Party, but in an effort to make better time, he traded his wagon for pack mules, and thus reached Blacks Fork a week ahead of the Donners. Bryant saw the first part of the trail, and was concerned that it would be difficult for the wagons in the Donner group, especially with so many women and children. He returned to Blacks Fork with letters warning several members of the group not to take the shortcut.[34] By the time the Donner Party reached Blacks Fork on July 27 Hastings had already left on his route, leading the 40 wagons of the Harlan-Young group.[31] Jim Bridger, whose trading post fared substantially better when people used the Hastings Cutoff, told the party that the shortcut was a smooth trip devoid of rugged country which would remove 350 miles (560 km) from their journey, and that the group would not encounter any hostile Indians. Water would be easy to find along the way, although a short distance of about 30–40 miles (48–64 km) over a dry lake bed would be necessary, but easily crossed in a couple of days. Reed was very impressed with this information and when the men in the party discussed what to do, he argued to take the Hastings Cutoff. None of the Donner Party members ever received Bryant's letters warning them to avoid Hastings' route at all costs.[35][36][note 4]

Hastings' route

Wasatch Mountains

The members of the party, if not wealthy, were comfortably well off by contemporary standards.[15] Although they are called pioneers, very few of them had experience living on the frontier. They were hardy farmers and businessmen, not unfamiliar with hard work, but they lacked specific skills and experience traveling through mountains and arid land, and had very little knowledge about how to deal with Native Americans, including how to ask for help or recognize when they may be hostile.[37] Tamsen Donner was, according to fellow emigrant J. Quinn Thornton, "gloomy, sad, and dispirited" at the thought of turning off the main trail on the advice of "a selfish adventurer".[38] Despite all this, on July 31, 1846, the party left Blacks Fork after four days of rest, wagon repairs, and some personnel changes, eleven days behind the leading Harlan-Young group. A new family named McCutcheon, consisting of a young couple with a baby, joined. Donner hired a new driver to replace one who had left, and a 16-year-old named Jean Baptiste Trudeau from New Mexico, who claimed to have knowledge of the Indians and terrain on the way to California, joined the company.[39]

The party turned south to follow Hastings' Cutoff and within days found the terrain to be much more difficult than had been described. The drivers had to lock the wagon wheels to keep them from sliding down steep inclines. Several years' of migration on the Oregon Trail had created an easy path on the main route to see and travel. The cutoff, however, was more difficult to find. Hastings wrote directions that he was just ahead and left letters for the Donner Party stuck to trees. On August 6, the party found a letter from Hastings, advising them to stop until Hastings could show them an alternate route from that taken by the Harlan-Young Party.[note 5] Reed, Charles Stanton, and William Pike (a son-in-law of Levinah Murphy) rode ahead to get Hastings. Reed and the others encountered exceedingly difficult canyons where boulders had to be moved and walls cut off precariously to a river below; it was a route that was likely to break wagons. Although Hastings had offered in the letter to guide the Donner Party around the more difficult areas, he only rode back with Reed partway, showing him the general direction in which they should be traveling.[40][41]

Stanton and Pike stopped to rest, and Reed returned alone to the group, arriving four days after the party's departure. Now without the guide they had been promised, the group had to decide whether to turn back and return to the traditional trail, follow the tracks left by the Harlon-Young Party through the difficult terrain of Weber Canyon, or forge their own trail in the direction Hastings had pointed out to Reed. At Reed's urging, the group chose to follow the path Hastings had suggested.[42] Their progress slowed considerably to about a mile and a half (2.4 km) a day. All the able-bodied men cleared brush, felled trees, and heaved rocks to clear room for the wagons, and the party quickly grew unhappy with the labor.[note 6]

As the Donner Party blazed its trail across the Wasatch Mountains, their numbers grew slightly when they were joined by the Graves family, an older couple with nine children, plus a son-in-law, and a teamster named John Snyder, traveling together in three wagons. The Graves included four young men who could assist with the work, and together they brought the total number of the Donner Party to 87 members in between 60 to 80 wagons.[43] The Graves family had been part of the last group to leave Missouri, providing confirmation that the Donner Party was at the rear of the year's western exodus.[44]

By the time they had reached a point in the mountains where they could look down and see the Great Salt Lake, it was August 20. It took almost another two weeks to travel down out of the Wasatch Mountains. Morale dipped to a new low, caused by the back-breaking labor. The men began to argue and doubts were cast against those who had decided to use this route, chief among them James Reed. Food and supplies for some of the less affluent families began to run out. Stanton and Pike, who had ridden out with Reed, had become lost on their way back; by the time the party found them, they had begun to starve and were a day away from eating their horses.[45]

Great Salt Lake Desert

Luke Halloran died on August 25, nursed to the end by Tamsen Donner. Out of reverence for his death, the party waited a day before resuming their journey. A few days later the party came across another letter from Hastings, this one torn and tattered in pieces. Tamsen Donner attempted to put it back together to see if it was a warning or another change in direction; it indicated that two days and two nights of difficult travel without grass or water was ahead of them. The party rested their oxen and prepared water, grass, and food for the ordeal.[46] They embarked after 36 hours, but were dismayed to find it necessary to traverse a 1,000-foot (300 m) mountain. When they got to the top and looked down, they saw a dry, barren plain, perfectly flat and covered with white salt, larger than the one they had just crossed.[47] It is an environment described by author Ethan Rarick as "one of the most inhospitable places on earth".[12] Their oxen were already fatigued and their water was nearly gone.[47]

With nowhere else to go, they went forward to find their wagon wheels sank into the salt. Families with lighter wagons and stronger oxen pulled ahead of the others. The days were blistering hot and the nights frigid. Several members of the party were confronted with visions of lakes and wagon trains; they believed they had finally overtaken Hastings, but the mirages disappeared.[note 7] After three days and no end in sight, some of the party removed their oxen from the wagons to go ahead to find water. Some of the oxen were so weakened they were left yoked to the wagons and abandoned. Reed forged ahead on horseback to see if he could locate water. All he found was a slight rise, and on the other side, another expanse of desert. He returned to find nine out of ten of his oxen had broken away and run loose in the desert to find water. Many other families' cattle and horses had also gone missing. Irreparable damage had been done to some of the wagons; Reed and his family suffered the greatest losses to property, but no human lives had been lost. The journey across the Great Salt Lake Desert took six days.[48][49]

No one in the party had any faith in the Hastings Cutoff by the time the company recovered among the springs on the other side of the desert. They spent several days trying to locate their cattle, then taking trips either to retrieve the wagons they had to leave in the desert, or simply taking the food and supplies and transferring them to other wagons.[note 8] Other members of the party agreed to carry Reed's excess food on condition that they could eat it. Although his family incurred the most damage, Reed became a more assertive leader at this point, asking all the families to submit an inventory of their goods and food to him. He suggested two men go to Sutter's Fort in California; he had heard that John Sutter was exceedingly generous to wayward pioneers, and could assist them with extra provisions. Charles Stanton and William McCutcheon, volunteered for the dangerous job, riding alone through unknown territory.[50] The remaining serviceable wagons were pulled by mongrel teams of cows, oxen, and mules. It was the middle of September, and two young men who went in search of missing oxen reported another stretch of desert 40 miles (64 km) long lay ahead.[51]

Reed banished

Although their cattle and oxen were exhausted and lean, the Donner Party crossed the next stretch of desert relatively unharmed and the journey seemed to get easier, particularly through the valley adjacent to the Ruby Mountains. Despite their near hatred of Hastings, they had no choice but to follow his wagon wheel tracks, which by this time were weeks old. The first day of autumn passed and the trail wound south, then north without any apparent reason.[note 9] On September 26, two months after embarking on the cutoff, the Donner Party rejoined the traditional trail along a stream that was to be known as the Humboldt River. By taking the shortcut, they had likely lost a full month of progress.[52][53]

Along the Humboldt the group met Paiute Indians they called Diggers, who joined them for a couple of days, but stole or shot several oxen and horses. By this time it was well into October and fights began to break out among the Donner Party. Jacob and George Donner split off to make better time. Reed was left with the group behind, to witness two wagons get tangled and the drivers shout names at each other. In control of one wagon, John Snyder (a teamster for the Graves family) became enraged and began to beat the ox of Reed's hired teamster, Milt Elliott. Reed intervened and Snyder turned the whip on him. Reed retaliated with a knife, fatally plunging it under Snyder's collarbone.[53][54]

That evening the witnesses gathered to discuss what was to be done; United States laws were not applicable west of the Continental Divide (in what was then Mexican territory) and wagon trains often dispensed their own justice.[55] The party had seen Snyder hit both James and Margaret Reed, but Snyder was popular and Reed was not. Keseberg suggested hanging Reed, going so far as to tip his wagon tongue up to use as an improvised gallows, but an eventual compromise allowed Reed to leave the camp without his family, who would be taken care of by the others. Reed departed alone the next morning, unarmed, after he assisted in burying Snyder.[56][57][58][note 10] Someone managed to ride ahead and secretly provide him with a rifle and food.[59]

Last advance

Disintegration

The trials the Donner Party had so far encountered resulted in splintered groups of families, employees, and associates which were each looking out for themselves and distrustful of others.[60][61] Grass was becoming scarce, and the animals were steadily weakening. To relieve the load, everyone was expected to walk.[62] Keseberg ejected Hardkoop from his wagon, telling the elderly man he had to walk or die. A few days later Hardkoop sat next to a stream, his feet so swollen they split open, and he was not heard from again. When William Eddy pleaded with other men to find Hardkoop they all refused, some angrily. They swore they would waste no more resources on a man who was nearly 70 years old.[63][64]

Reed caught up with the Donners and went on with one of his teamsters, Walter Herron. Although the two shared a horse, they were able to cover between 25–40 miles (40–64 km) per day.[65] The rest of the party rejoined the Donners, but their luck continued to decline. Indians chased away all of Graves' horses and another wagon was left behind. With grass in short supply the cattle spread out more, which allowed the Paiutes to steal 18 more head during one evening, and several mornings later, shoot another 21.[66] So far the company had lost nearly 100 oxen and cattle, and their rations were almost completely depleted. One more stretch of desert lay ahead. The Eddys' oxen had all been killed by Indians and they were forced to abandon their wagon. The family had eaten all their stores, but the other families refused to assist their children, a 3-year-old boy and an infant girl. Eleanor Eddy had to carry the girl and William Eddy carried his son, who were so miserable with thirst through this phase that Eddy was certain they were dying. Margaret Reed and her children were also forced to leave their wagon and carried only a change of clothing.[67][68] The desert soon came to an end, however, and the party found the Truckee River in beautiful lush country.[68]

They had little time to rest, and the company pressed on to cross the mountains before the snows came. Spitzer and Reinhardt found the party to report that they and Wolfinger, who had stopped to "dig a cache", or bury his wagon to keep it from being vandalized by animals or Indians, had been attacked by Paiutes, and Wolfinger had been killed.[69] Countering this bad news, Stanton, one of the two-man party who had left a month earlier to gain assistance in California, found the company and brought mules, food, and two vaqueros—Luís and Salvador, converted Indians hired by Sutter. Stanton brought news that Reed and Herron, although haggard and starving, had made their way to Sutter's Fort in California, and made it his duty to watch over the Reed family.[70][71] By this point, according to author Ethan Rarick, "To the bedraggled, half-starved members of the Donner Party, it must have seemed that the worst of their problems had passed. They had already endured more than many emigrants ever did."[72]

Snowbound

The ragtag company faced a decision between resting their cattle for one last push over the mountains that were described as much worse than the Wasatch, or forging ahead. They had been told that the pass would not be snowed in until the middle of November, and on October 20, they sat and pondered what they should do. They waited a few days to consider their decision. In the meantime, William Pike, a married father, was killed when a gun being loaded by William Foster discharged accidentally.[73] Pike's death seemed to make the decision for them, and family by family, they began to go, first the Breens, then Kesebergs, Stanton with the Reeds, Graves, and Murphys. The Donners waited and traveled last. After a few miles of rough terrain, an axle broke on one of the Donners' wagons. Jacob and George went into the woods to fashion a replacement. While chiseling the wood, the instrument slipped and sliced George Donner's hand open, but it seemed a superficial wound.[74]

Snow began to fall. The Breens made it up the "massive, nearly vertical slope" 1,000 feet (300 m) to Truckee Lake, 3 miles (4.8 km) from the summit, and camped near a cabin that had been built two years earlier by another group of pioneers.[75][note 11] The Eddys and Kesebergs joined the Breens, attempting to make it over the pass, but they found 5–10-foot (1.5–3.0 m) drifts of snow, and were unable to locate the trail. They turned back for Truckee Lake and within a day all the families were camped there except for the Donners, who were 5 miles (8.0 km)—half a day's journey—below them. One last time they mustered the strength to cross over the pass, but the snow was too high, the animals and people too exhausted, and they laid down and decided to rest on November 4. That evening it began to snow again. The next morning they found the summit impassable, and were forced to spend all day returning to Truckee Lake and the pioneer cabin.[76]

Winter camp

Reed attempts a rescue

Although James Reed was safe and recovering in Sutter's Fort, each day he became more worried about the fate of his family and friends. He pleaded with Colonel John C. Frémont to gather a team of men to cross the pass and help the company, even the ones who had exiled him. In return, Reed promised he would join Frémont's forces and fight in the Mexican-American War.[77] McCutcheon, who had gone with Stanton but had fallen ill and was unable to return with Stanton, joined Reed in hopes of finding out how his wife and child were faring. The party of roughly 30 horses and a dozen men carried food stores and expected to find the Donner Party near Bear Valley, starving but alive. When they arrived in Bear Valley they found instead a pioneer couple, emigrants who had been separated from their company, trying to reach Sutter's Fort. The couple offered Reed and McCutcheon their roast dog. A storm had made it impossible for them to cook, so the men had not eaten for 24 hours. After a moment of hesitation Reed and McCutcheon accepted, and found the roast dog very palatable.[78][79] In return, Reed and McCutchean shared some of their provisions with the couple.[80]

Two guides deserted Reed and McCutcheon with some of their horses, but they pressed on to Yuba Bottoms, walking the last mile on foot. On possibly the same day that the Breens attempted to lead one last effort to crest the pass, Reed and McCutcheon stood looking at the other side only 12 miles (19 km) from the top, blocked by snow. Despondent, they turned back to Sutter's Fort.[81]

On the other side of the pass at Truckee Lake, 60 members and associates of the Breen, Graves, Reed, Murphy, Keseberg, and Eddy families set up for the winter. Three cabins of pine logs built far apart, with dirt floors and poorly constructed flat roofs that leaked when it rained, served as their homes. The Breens, who had lost the fewest cattle, inhabited one cabin, the Eddys and Murphys another, and Reeds and Graves the third. Keseberg built a lean-to for his family next to the Breen cabin. The families used canvas or oxhide to patch the faulty roofs. The cabins had no windows or doors, only large holes to allow entry. Nineteen of the sixty at Truckee Lake were males older than eighteen years. Twelve were women and twenty-nine were children, six of whom were toddlers or younger. Farther down the trail, close to Alder Creek, the Donner families hastily constructed tents to house twenty-one people, including Mrs. Wolfinger, her child, and the Donners' drivers: six men, three women, and twelve children in all.[82][83]

All the food stores were gone in both camps. Most of what Stanton had brought was also used. The oxen began dying naturally of starvation and their carcasses were frozen and stacked. Truckee Lake was not frozen over, but the snowbound pioneers were unfamiliar with catching lake trout. Eddy, who was the most experienced hunter, killed a bear, but had little luck after that. The Reed and Eddy families had lost almost everything and Margaret Reed promised to pay double when they got to California for the use of three oxen from the Graves and Breen families. The bitter divides between the members only became worse in camp; Graves had an ox that starved to death, for which he charged Eddy $25 ($600 in 2010).[84][85]

The Forlorn Hope

| Members of the Forlorn Hope | |

|---|---|

| Name | Age |

| Antonio* | 23‡ |

| Luís* | unk |

| Salvador* | unk |

| Charles Burger† | 30‡ |

| Patrick Dolan* | 35‡ |

| William Eddy | 28‡ |

| Jay Fosdick* | 23‡ |

| Sarah Fosdick | 21 |

| Sarah Foster | 19 |

| William Foster | 30 |

| Franklin Graves* | 57 |

| Mary Ann Graves | 19 |

| Lemuel Murphy* | 12 |

| William Murphy† | 10 |

| Amanda McCutcheon | 23 |

| Harriet Pike | 18 |

| Charles Stanton* | 30 |

| * died en route † turned back before reaching pass ‡estimated age[86] | |

Desperation grew in camp and some of the members reasoned if the wagons could not make it out, individuals might be able to. In small groups they made several attempts, but each time turned back, defeated. They planned to go again within days, but another severe storm arose lasting more than a week, covering the area so deeply that the cattle and horses—their only remaining food—laid down, died, and were lost and buried in the snow.[87]

The mountain party at Truckee Lake began to fall. Spitzer, then Baylis Williams, a driver for the Reeds, died, more from malnutrition than starvation. Franklin "Uncle Billy" Graves, who believed he was being punished by God for not having returned to find the elderly man Hardkoop,[88] fashioned fourteen pairs of snowshoes out of oxbows and hide. A party of seventeen volunteers, men, women, and children, set out on foot in an attempt to cross the mountain pass.[89] As evidence of how grim their choices were, four of the men were fathers, and three of the women mothers who gave their young children to other women. They packed lightly, taking what had become six days' rations, a rifle, a blanket each, a hatchet, and some pistols, hoping to make their way to Bear Valley.[90] Historian Charles McGlashan later called this snowshoe party "The Forlorn Hope".[91] Two turned back early on, Charles Burger and 10-year-old William Murphy. He and his older brother Lemuel had no snowshoes, the idea being that the lighter members of the party could walk in the footsteps of those who did, but that turned out to be "utterly impractical".[92] Other members of the party fashioned a pair of snowshoes for Lemuel on the first evening, from one of the packsaddles they were carrying.[92]

The snowshoes proved to be awkward but effective on the arduous climb over the pass. The members of the party were neither well-nourished nor accustomed to camping in snow 12 feet (3.7 m) deep, and by the third day most of them were snowblind. On the sixth day Eddy discovered his wife had hidden a half-pound of bear meat in his pack for him. The group set out on the morning of the sixth day, December 21, leaving Stanton, who had been straggling behind several days in a row, sitting on a stump smoking his pipe, saying he would be following shortly. His remains were found the following year.[93][94]

The group became lost and confused. A storm came upon them and they huddled together, trying to decide what to do. After two more days of not eating, Patrick Dolan finally suggested that one of them should volunteer to die, to feed the others. A discussion ensued about how it might be done, with a suggestion that two people with pistols could square off and whoever lost would be eaten. Another account states that they attempted to create a lottery, where the loser would be killed by someone else in the group.[94][95] Eddy suggested they continue to move until someone simply fell. Antonio, the animal handler, was the first to die the next morning. A vicious storm arose and they were running out of firewood. While someone went to cut more wood the hatchet head flew off into the snow and was lost. The fire they built was sinking into the snow making a hole, creating chilly water that crept into their clothes. "Uncle Billy" Graves died next, but Eddy managed to get the rest of the surviving members out of the hole and for three days they sat on a blanket in a tight circle and covered themselves with more blankets.[96][97]

Patrick Dolan began mumbling incoherently, stripped off his clothes, and ran into the woods. He returned shortly, quieter, and died a few hours later. Finally, facing the death of 12-year-old Lemuel Murphy, some of the group cut into Patrick Dolan's body, turned away from each other, cried, and ate his flesh. Lemuel's sister fed some to her brother, but he died shortly afterwards. Eddy held out and refused. So did Salvador and Luís, who built a fire apart from the others and watched. The next morning they stripped the muscle and organs from the the bodies of Antonio, Dolan, Graves, and Murphy and dried it to store for the days ahead, taking care to ensure that no family member had to eat his or her relatives.[98][99]

They recuperated for three days, and set off again trying to find the trail. The oxhide straps and webbing in the snowshoes became brittle from constant moisture and drying. Most of the party members were frost-bitten and their feet left a trail of blood in the snow. After four days, Eddy succumbed to his hunger and ate human flesh. Soon that was gone, too. They began to take apart their snowshoes and eat the oxhide webbing. They seriously discussed killing Luís and Salvador to eat them, but Eddy protested and told the Indians. Following an initial look of astonishment, Luís and Salvador quietly left.[100] Eddy decided to go with Mary Graves on a hunting expedition, much to the consternation of the rest of the group, who had come to rely on him and feared he may become lost, leaving them to die.[101][note 12] They walked for 2 miles (3.2 km) until, overcome by exhaustion and emotion, both burst into tears and decided to pray. A deer appeared, but Eddy was so weak he was unable to hit it. After taking two shots, with Mary Graves behind him weeping, he was forced to raise the gun higher than his target and try to hit the deer on the way down. His third shot was successful.[102]

During the night Jay Fosdick, who was with the rest of the snowshoe party, died, leaving only a total of seven. Eddy and Mary Graves returned with the deer meat, but Fosdick's body was cut apart for food. The effects of starvation and hypothermia began to take their toll emotionally. They were unable to walk steadily and sometimes the women fell and sobbed uncontrollably. They were listless and sometimes apathetic. Foster and Eddy began to fight with each other until the women intervened.[103][104] Again they ventured forth to try to find the trail, still hopelessly lost. After several more days—25 since they had left Truckee Lake—they came across Salvador and Luís, who had not eaten anything for about nine days and were hours from death. William Foster, who had recently suggested killing Amanda McCutcheon for lagging behind, took a pistol and shot the Indians, allowing Salvador to say a final prayer before stripping the bodies of muscle and organs. On January 12, they stumbled into a Miwok camp looking so deteriorated the Indians fled at the sight of them. After a brief return, the Miwoks gave them what they had to eat: acorns, grass, and pine nuts.[105] Eddy was revived after a few days and propelled them forward with the help of a Miwok, although the other six simply laid down in the snow, too far gone to care. Eddy and the Indian walked 5 miles (8.0 km), met another Indian who, with the lure of tobacco, half-carried Eddy to a ranch at the edge of the Sacramento Valley. A rancher's daughter named Harriet Ritchie opened the door to find Eddy, supported by two Indians, and let out a sob at his condition.[106][107]

The small farming community of emigrants from the eastern U.S. assembled quickly and found the other six members of the snowshoe party alive. They were allowed to eat as much as they wanted and all of them vomited from gorging. It was January 17, 33 days after their departure from Truckee Lake.[108][109]

Truckee Lake

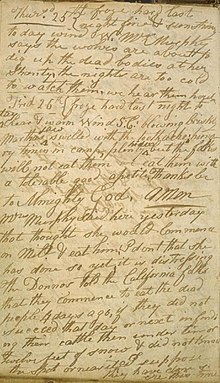

Patrick Breen began keeping a diary in November, a few days before the snowshoe party left. He primarily concerned himself with the weather, marking the storms and how much snow had fallen, but gradually began to include references to God and religion in his entries.[110] Life at Truckee Lake was miserable. The cabins were cramped and it snowed so much that people were unable to go outdoors for days. Conditions were filthy. Diets soon consisted of oxhide tallow, made from boiling strips of hide into a nauseating gelatin. Ox and horse bones were boiled repeatedly to make soup, and became so brittle they would crumble upon chewing. Sometimes they were softened by being charred and eaten. A rug of oxhide lay in front of the fireplace in the Murphy cabin. Bit by bit, the children picked apart the hide rug, roasted it in the fire and ate it until the rug was gone.[111] After the departure of the snowshoe party, two-thirds of the emigrants at Truckee Lake were children. Mrs. Graves was in charge of eight, and Levinah Murphy and Eleanor Eddy together took care of nine.[112] Mice that strayed into the cabins became food when the emigrants were able to catch them. Many of the people at Truckee Lake were soon weakened and spent most of their time in bed. Occasionally one would be able to make the full day trek to see the Donners. News came that Jacob Donner and three hired men died. One of them, Reinhardt, confessed on his death bed that he had murdered Wolfinger.[113] George Donner's hand became infected, which left four able men to work at the Donner camp.[114]

Mrs. Reed had managed to save enough food for a Christmas pot of soup, to the delight of her children, but by January they were facing starvation and considered eating the oxhides that served as their roof. Mrs. Reed, Virginia, Milt Elliott and the servant girl Eliza Williams attempted to walk out, reasoning that they could do better to bring food back than sit and watch the children starve. They were gone four days in the snow before they had to turn back. Their cabin was now uninhabitable; the oxhide-roof now served as their food supply, and the family moved in with the Breens. The servants went to live with other families. One day the Graves came by to claim their payment of the oxhides Mrs. Reed had, which was all the Reed family had to eat.[115][116]

Rescue

Most of the military in California, and with them the able-bodied men, were engaged in the Mexican-American War. Reed kept his promise to Frémont and fought in the Battle of Santa Clara.[117] Throughout the region roads were blocked, communications compromised, and supplies unavailable. Only three men responded to a call for volunteers to rescue the Donner Party. Reed was laid over in San Jose until February because of regional uprisings and general confusion. He spent that time speaking with other pioneers and acquaintances, and the people of San Jose responded by creating a petition to appeal to the U.S. Navy to assist the people at Truckee Lake. Two local newspapers reported that members of the snowshoe party had resorted to cannibalism, which helped to foster sympathy for those who were still trapped. In Yerba Buena, about 200 men, most of them emigrants themselves, attended a meeting where Reed was overcome with his fears and, unable to speak, sat down and cried.[118] The men raised $1,300 ($30,000 in 2010) and relief efforts were organized to build two camps to supply a rescue party and the refugees.[119][120]

A rescue party of fourteen men, including William Eddy, started on February 4 from the Sacramento Valley. Rain and a swollen river forced several delays. Eddy stationed himself at Bear Valley and the others made steady progress through the snow and storms to cross the pass to Truckee Lake, caching their food at stations so they did not have to carry all of it, and suspending it from trees to keep it out of reach from bears. Three of the rescue party turned back, and seven forged on. During this period Breen's journal contains more frequent mentions of deaths, including those of Eleanor Eddy, her infant daughter, and Milt Elliott.[121][122]

First relief

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On February 18, the seven-man rescue party scaled Frémont Pass; as they neared where Eddy told them the cabins would be, they began to shout. Mrs. Murphy appeared from a hole in the snow, stared at them and asked, "are you men from California, or do you come from heaven?"[123] The rescuers were astonished by the living conditions. All the emigrants were emaciated; the relief party doled out food in small portions, concerned that if the emigrants overate it would kill them. All the cabins were buried in snow. Oxhide roofs wet with moisture had begun to rot and the smell was overpowering. The bodies of the dead had been loosely buried in snow near the cabin roofs. Some of the emigrants seemed emotionally unstable. Three of the rescue party trekked to the Donners and brought back four gaunt children and two adults. Leanna Donner had particular difficulty walking up the steep incline from Alder Creek to Truckee Lake, later writing "such pain and misery as I endured that day is beyond description."[124] George Donner's arm was so gangrenous that he could not move, but no one at Alder Creek had died since the last visit. Twenty-three people were chosen to go with the rescue party, including the Reeds, three adolescent Graves children, two older Murphy children, Mrs. Keseberg and her 3-year-old daughter Ada. This left seventeen people in the cabins at Truckee Lake and twelve at Alder Creek.[125][126]

The rescuers concealed the fate of the snowshoe party, informing the rescued emigrants only that they did not return because they were frostbitten.[127] Patty and 3-year-old Tommy Reed were soon too weak to cross the snowdrifts, and no one was strong enough to carry them. Margaret Reed faced the agonizing predicament of accompanying her two older children to Bear Valley and watching her two frailest be taken back to Truckee Lake without a parent. She made one of the rescuers, Aquilla Glover, swear on his honor as a Mason that he would return for her children. Patty Reed told her resolutely, "Well, mother, if you never see me again, do the best you can."[128][129] Upon their return to the lake, the Breens flatly refused them entry to their cabin, but after Glover left more food the children were grudgingly admitted. The entire rescue party was dismayed to find the first cache station had been mauled by animals so they had no food for four days. Englishman John Denton and young Ada Keseberg had much difficulty on the the walk over the pass; Denton slipped into a coma, and revived briefly before dying the next day. Ada died soon afterward; her mother was inconsolable, refusing to let the child's body go. After several days' more travel through difficult country, the rescuers grew very concerned that the children would not survive. Some of them ate the buckskin fringe from one of the rescuer's pants and the shoelaces of another, to the relief party's surprise. On their way down from the mountains they met the next rescue party, which included James Reed. Upon hearing his voice, Margaret sank into the snow, overwhelmed.[130][131]

After these rescued emigrants made it safely into Bear Valley, William Hook, who was a stepson of Jacob Donner, broke into food stores and fatally gorged himself. The others continued to Mule Springs then to Sutter's Fort where Virginia Reed wrote "I really thought I had stepped over into paradise". She was amused to note that although she was only twelve years old and was recovering from starvation, one of the young men asked her to marry him.[132][133]

Second relief

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On March 1, a second relief party arrived at Truckee Lake. These rescuers were mostly experienced mountaineers who accompanied the return of Reed and McCutcheon. Reed was reunited with his daughter Patty and his weakened son Tommy. An inspection of the Breen cabin found its occupants relatively well, but the Murphy cabin, according to author George Stewart, "passed the limits of description and almost of imagination". Levinah Murphy, who was caring for her eight-year-old son Simon and the two young children of William Eddy and Foster, had deteriorated mentally and was nearly blind. The young children were listless and had not been cleaned in days. Lewis Keseberg had moved into the cabin and could barely move due to an injured leg.[134]

No one at Truckee Lake had died during the interim between the departure of the first relief party and the arrival of the second relief party. Patrick Breen recorded that an Indian had silently approached the cabins, warned the emigrants to stay away, placed several soaproots on the snow and left. Breen also documented a disturbing visit in the last week of February from Mrs. Murphy, who said her family was considering eating Milt Elliott. Reed and McCutcheon found Elliott's mutilated body.[135] The Alder Creek camp fared no better, with the mostly dismembered body of Jacob Donner lying outside. Inside the tent, Elizabeth Donner refused to eat, although her children were being nourished by the organs of their father.[136] The rescuers discovered that three other bodies had already been consumed. In the other tent, Tamsen Donner was well, but George was very ill because the infection had reached his shoulder.[137]

The second relief evacuated seventeen emigrants, only three of whom were adults, from Truckee Lake. Both the Breen and Graves families prepared to go. Only five people remained at Truckee Lake: Keseberg, Mrs. Murphy and her son Simon, and the young Eddy and Foster children. Tamsen Donner elected to stay with her ailing husband after Reed informed her that a third relief party would arrive soon. Mrs. Donner kept her daughters Eliza, Georgia, and Frances with her.[138]

The walk back to Bear Valley was very slow; at one point Reed sent ahead two of the men to retrieve the first cache of food, expecting the third relief, a small party led by Selim E. Woodworth, to come at any moment. A violent blizzard arose after they scaled the pass, which cowed some of the more experienced mountaineers and sent the children into hysterics for two nights. Five-year-old Isaac Donner froze to death, and Reed nearly died. Mary Donner's feet were so frostbitten that she did not realize she was sleeping with her feet in the fire and they became badly burned. When the storm passed, the Breen and Graves families, not having eaten for days, were too apathetic and exhausted to get up and move. The relief party had no choice but to leave without them.[139][140][141]

Three members of the relief party stayed, one at Truckee Lake and two at Alder Creek. When one, Nicholas Clark, went hunting, the other two, Charles Cady and Charles Stone, made plans to return to California. Tamsen Donner arranged for them to carry three of her children to California, perhaps, according to Stewart, for $500 cash ($11,702 in 2010). Cady and Stone took the children to Truckee Lake but then left, alone, overtaking Reed and the others within days.[142][143]

William Foster and William Eddy, both survivors of the snowshoe party, started from Bear Valley to intercept Reed, taking with them a man named John Stark. In a day, they met Reed, helping his children, all frostbitten and bleeding, but alive. Desperate to rescue their own children, Foster and Eddy persuaded four men, with pleading and money, to return to Truckee Lake with them. Halfway there they found the crudely mutilated and eaten remains of two children and Mrs. Graves.[144] Eleven survivors were huddled around a fire that had sunk into a pit. The relief party split, with Foster and Eddy headed toward Truckee Lake. Two rescuers, hoping to save the healthiest, each took a child and left. John Stark refused to leave the others. Stark picked up two children and all the provisions, and assisted the nine remaining Breens and Graves to Bear Valley.[145][146][147][note 14]

Third relief

| ||||||||||||||

Foster and Eddy finally arrived at Truckee Lake on March 14, where they found both of their children dead. Keseberg told Eddy that he had eaten the remains of Eddy's son, and Eddy swore to murder Keseberg if they ever met in California.[149][note 15] Tamsen Donner had just arrived at the Murphy cabin after learning that her three children were still there. George Donner and one of the Donner children were still alive at Alder Creek. Tamsen Donner could walk out alone, but chose to return to her husband although she was informed that no other relief party was likely to be coming soon. Foster and Eddy and the rest of the third relief left with four children, Trudeau, and Clark to go over the pass one more time.[150][151]

Two more relief parties were mustered to evacuate any adults who might still be alive. Both additional relief parties turned back before getting to Bear Valley, and no further attempts were made. On April 10, almost a month since the third relief had left Truckee Lake, the alcalde near Sutter's Fort organized a salvage party to bring in what they could of the Donner's belongings. The belongings would be sold, with part of the proceeds used to support the orphaned Donner children. The salvage party found the Alder Creek tents empty except for the body of George Donner, who had died only days earlier. On their way back to Truckee Lake they found Keseberg alive. According to Keseberg, Mrs. Murphy had died one week after the departure of the third relief. Some weeks later, Tamsen Donner arrived at Keseberg's cabin on her way over the pass. She was soaked and visibly upset. Keseberg said he put a blanket around her and told her to start out in the morning, but when morning came she was dead. The salvage party did not believe Keseberg. They found a pot full of human flesh in the cabin along with George Donner's pistols, jewelry, and $250 in gold. They threatened to lynch Keseberg, who confessed that he had cached $273 of the Donners' money, at Tamsen's instigation, so that it could one day benefit her children.[152][153]

Response

"A more revolting or appalling spectacle I never witnessed. The remains here, by order of Gen. Kearny collected and buried under the superintendence of Major Swords. They were interred in a pit which had been dug in the centre of one of the cabins for a cache. These melancholy duties to the dead being performed, the cabins, by order of Major Swords, were fired, and with every thing surrounded them connected with this horrid and melancholy tragedy, were consumed. The body of George Donner was found at his camp, about eight or ten miles distant, wrapped in a sheet. He was buried by a party of men detailed for that purpose."

Member of General Stephen W. Kearny's company, June 22, 1847[154]

News of the Donner Party's fate was spread eastward by Samuel Brannan, an elder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints who encountered the salvage party as they came down from the pass with Keseberg.[155] Accounts of the ordeal first reached New York City by sea in July 1847. Reporting on the event across the U.S. was heavily influenced by the national enthusiasm for westward migration. In some papers, news of the tragedy was buried in small paragraphs despite the contemporary tendency to sensationalize stories. Several newspapers, including those in California, wrote about the cannibalism in graphic exaggerated detail.[156] In some print accounts, the members of the Donner Party were made to be heroes, and California a paradise worthy of significant sacrifices.[157]

Emigration to the west decreased in the wake of news about the Donner Party. In 1846, an estimated 1,500 people migrated to California. In 1847 the number dropped to 450 and to 400 in 1848. The ongoing Mexican-American War may also have deterred emigration. The California Gold Rush spurred a sharp increase however, and in 1849, 25,000 people went west.[158] Most of the overland migration followed the Carson River, but a few forty-niners used the same route as the Donner Party and recorded descriptions about the site.[159] The areas inhabited by the party were so notorious that they became known as Donner Pass, Donner Lake, and Donner Peak.

In late June 1847 a military detail under General Steven Kearny buried the human remains,[159] and partially burned two of the cabins. The few who ventured over the pass in the next few years found bones, other artifacts, and the cabin used by the Reed and Graves families. In 1891 a cache of money was found buried by the lake. It had probably been stored by Mrs. Graves, who hastily hid it when she left with the second relief so that she could return for it later.[160][161]

Survivors

Of the 87 members who entered the Wasatch Mountains, 45 people survived and 42 died. Only the Reed and Breen families were intact. The children of Jacob Donner, George Donner, and Franklin Graves were orphaned. William Eddy was alone; most of the Murphy family had died. Only three mules reached California; the remaining animals perished. The majority of the Donner Party members' possessions were discarded.[162]

"I have not wrote to you half the trouble we have had but I have wrote enough to let you know that you don't know what trouble is. But thank God we have all got through and the only family that did not eat human flesh. We have everything but I don't care for that. We have got through with our lives but Don't let this letter dishearten anybody. Never take no cutoffs and hurry along as fast as you can."

Virginia Reed to cousin Mary Keyes, May 16, 1847[note 16]

A few of the widowed women remarried within months; brides were scarce in California. The Reeds settled in San Jose and two of the Donner children lived with them. Reed fared well in the California Gold Rush and became prosperous. Virginia, with editorial oversight from her father, wrote an extensive letter to her cousin in Illinois about "our trubels getting to Callifornia" [sic]. Journalist Edwin Bryant carried it back in June 1847, and it was printed in its entirety, with some editorial alterations, in the Illinois Journal on December 16, 1847.[163] Virginia converted to Catholicism in fulfillment of a promise she had made to herself while observing Patrick Breen pray in his cabin. The Murphy survivors lived in Marysville. The Breens made their way to San Juan Bautista[164] where they ran an inn and became the anonymous subjects of one writer's story about his severe discomfort upon learning he was staying with professed cannibals, printed in Harper's Magazine in 1862. Many of the survivors encountered similar reactions.[165] George and Tamsen Donner's children were taken in by an older couple near Sutter's Fort. The youngest of the Donner children, Eliza, who was three years old during the winter of 1846–1847, published an account of the Donner Party in 1911, based on printed accounts and those of her sisters.[166] The Breen's youngest daughter Isabella, who was one year old during the winter of 1846–1847, became the last survivor of the Donner Party. She died in 1935.[167]

"I will now give you some good and friendly advice. Stay at home,—you are in a good place, where, if sick, you are not in danger of starving to death."

Mary Graves to Levi Fosdick (her sister Sarah Fosdick's father-in-law), 1847[168]

The Graves children lived varied lives. Mary Graves married early, but her first husband was murdered; she cooked his killer's food while he was in prison to ensure the condemned man did not starve before his hanging. One of Mary's grandchildren noted she was very serious; Graves once said, "I wish I could cry but I cannot. If I could forget the tragedy, perhaps I would know how to cry again."[169] Mary's brother William did not settle down for any significant time. Nancy Graves, who was nine years old during the winter of 1846–1847, refused to acknowledge her involvement even when contacted by historians interested in recording the most accurate versions of the episode; Nancy was reportedly unable to recover from her role in the cannibalism of her brother and mother.[170]

Eddy remarried and started a family in California. He attempted to make good on his promise to murder Lewis Keseberg, but James Reed and Edwin Bryant persuaded him to return to his family. A year later, Eddy recollected his experiences to J. Quinn Thornton, who, also using Reed's memories of his experiences, wrote the earliest comprehensive documentation of the episode.[171] Eddy died in 1859.

Keseberg brought a defamation suit against several members of the relief party who accused him of murdering Tamsen Donner. The court awarded him $1 in damages, but also made him pay court costs. An 1847 story printed in the California Star described Keseberg's near-lynching by the salvage party and his actions in ghoulish terms, reporting that he preferred eating human flesh to the cattle and horses that had become exposed in the spring thaw. Charles McGlashan, a historian, amassed enough material to indict Keseberg for the murder of Tamsen Donner, but after interviewing Keseberg concluded that no murder occured. Eliza Donner Houghton also believed Keseberg to be innocent.[172] As Keseberg grew older, he did not venture outside, for he had become a pariah and was often threatened. He told McGlashan "I often think that the Almighty has singled me out, among all the men on the face of the earth, in order to see how much hardship, suffering, and misery a human being can bear!"[173]

Legacy

Hundreds of thousands of emigrants populated Oregon and California via overland trails. Historian Kristin Johnson writes that the Donner Party episode itself is minor, and its impact was insignificant in light of the California Gold Rush.[174] However, the Donner Party has served as the basis for numerous works of history, fiction, drama, poetry, and film. The attention directed to the 87 members of the Donner Party is made possible by reliable accounts of what occurred, according to Stewart, and the fact that "the cannibalism, although it might almost be called a minor episode, has become in the popular mind the chief fact to be remembered about the Donner Party. For a taboo always allures with as great strength as it repels".[175] Charles McGlashan, whose history of the Donner Party precedes Stewart's, wrote that the story is "more thrilling than romance, more terrible than fiction".[176] The appeal according to Johnson, writing in 1996, is that the events focused on families and ordinary people instead of rare individuals, and that the events are "a dreadful irony that hopes of prosperity, health, and a new life in California's fertile valleys led many only to misery, hunger, and death on her stony threshold".[174]

The site of the cabins became a tourist attraction as early as 1854.[177] In the 1880s, Charles McGlashan began promoting the idea of a monument to mark the site of the Donner Party episode. He helped to acquire the land for a monument to be built on, and in June 1918, the statue of a pioneer family was placed on the spot where the Breen-Keseberg cabin was thought to have been, dedicated to the Donner Party.[178] It was made a California Historical Landmark in 1934.[179]

The State of California created Donner Memorial State Park in 1927, originally consisting of 11 acres (0.045 km2) surrounding the monument. Twenty years later, the site of the Murphy cabin was purchased and added to the park.[180] In 1962, the Emigrant Trail Museum was added to tell the history of westward migration into California. The Murphy cabin and Donner monument were established as a National Historic Landmark in 1963. A large rock served as the back end of the fireplace of the Murphy cabin, and a bronze plaque has been affixed to the rock listing the members of the Donner Party, indicating who survived and who did not. The State of California justifies memorializing the site because the episode was "an isolated and tragic incident of American history that has been transformed into a major folk epic".[181] As of 2003, the park is estimated to receive 200,000 visitors a year.[182]

Lansford Hastings received death threats, but started a law practice in California. An emigrant who crossed before the Donner Party confronted Hastings about the difficulties they had encountered, reporting "Of course he could say nothing but that he was very sorry, and that he meant well".[183] Hastings was a Confederate sympathizer who dreamed a plan to make Arizona and California a part of the Confederacy, but nothing came of it. At the time of his death, he was trying to establish a colony for Confederates in Brazil.[184]

Mortality

Although most historians count 87 members of the party, Stephen McCurdy in the Western Journal of Medicine includes Sarah Keyes—Margaret Reed's mother—and Luís and Salvador, bringing the number to 90.[185] Six people had already died before the party reached Truckee Lake: two from tuberculosis (Keyes, Halloran), three from trauma (Snyder, Wolfinger, Pike), and one from exposure (Hardkoop). A further 35 died between December 1846 and April 1847, 25 males and 10 females.[186] Several historians and other authorities have studied the mortalities to determine what factors may affect survival in nutritionally deprived individuals. Of the 15 members of the snowshoe party, 8 of the 10 men who set out died (Stanton, Dolan, Graves, Murphy, Antonio, Fosdick, Luís, Salvador), but all 5 of the women survived. J. Quinn Thornton, writing in 1864, attributed the discrepancy in survival rates between males and females to differences in temperament: "The difficulties, dangers, and misfortunes, which frequently seemed to prostrate the men, called forth the energies of the gentler sex, and gave them elevation of character, which enabled them to abide the most withering blasts of adversity with unshaken firmness".[187] A professor at the University of Washington stated that the Donner Party episode is a "case study of mediated natural selection in action".[188]

The deaths at Truckee Lake, Alder Creek, and in the snowshoe party, were probably caused by a combination of extended malnutrition, overwork, and exposure to cold. Several members, such as George Donner, became more susceptible to infection due to starvation,[189] but the three most significant factors in survival were age, sex, and the size of family group each member traveled with. The survivors were on average 7.5 years younger than those who died;[186] children aged between 6 and 14 had a high survival rate, while infants and children under the age of 6 and adults over the age of 35 had low survival rates. Deaths among males aged between 20 and 39 were "extremely high" at more than 66 percent. Men have been found to metabolize protein faster, and women do not require as high a caloric intake. Women also store more body fat, which delays the effects of physical degradation caused by starvation and overwork. Men also tend to take on more dangerous tasks, increasing their mortality; in this particular instance, the men were required before reaching Truckee Lake to clear brush and engage in heavy labor, adding to their physical debilitation. People traveling with family members survived more than the bachelor men, possibly because family members more readily gave each other food. Those traveling alone, however, may have been less psychologically or physically fit than those with families.[185][190] Eliza Farnham published an account of the Donner Party in 1856 in a book titled California, In-doors and Out, the premise of which was based upon the roles women played in the events.[191]

Claims of cannibalism

Some survivors disputed the accounts of cannibalism. Charles McGlashan, who corresponded with many of the survivors over a 40-year period, documented many recollections of cannibalism. Some correspondants were not forthcoming, approaching their participation in cannibalism with shame, while others eventually spoke about it freely. McGlashan in his 1879 book History of the Donner Party declined to include some of the more morbid details about suffering—such as what was endured by children and infants before dying, or how Mrs. Murphy, in the memories of Georgia Donner, gave up, laid down on her bed and faced the wall when the last of the children were leaving in the third relief. He also neglected to mention any of the cannibalism at Alder Creek.[192][193] The same year McGlashan's book was published, Georgia Donner wrote to him to clarify some points, saying that human flesh was prepared for people in both tents at Alder Creek, but to her recollection (she was four years old during the winter of 1846–1847) it was given only to the youngest children: "Father was crying and did not look at us the entire time, and we little ones felt we could not help it. There was nothing else." She furthermore remembered that Elizabeth Donner, Jacob's wife, announced one morning that she had cooked the arm of Samuel Shoemaker, a 25-year-old teamster.[194] Eliza Donner Houghton, in her 1911 account of the ordeal, did not mention any cannibalism at Alder Creek. Archeological findings at the Alder Creek camp proved inconclusive for evidence of cannibalism.[195]

Eliza Farnham's account of the Donner Party was based largely on an interview with Margaret Breen. This version details the ordeals of the Graves and Breen families after James Reed and the second relief left them in the snow pit. According to Farnham, seven-year-old Mary Donner suggested to the others that they should eat Isaac Donner, Franklin Graves, Jr., and Elizabeth Graves, because the Donners had already begun eating the others at Alder Creek, including Mary's father Jacob. Margaret Breen remained steadfast that she and her family did not join the Graveses in cannibalizing the dead while in the snow pit. Kristin Johnson, Ethan Rarick, and Joseph King—whose account is sympathetic to the Breen family—do not consider it credible that the Breens, who had been without food for nine days, would have been able to survive without eating human flesh. King suggests Farnham included this into her account independently of Margaret Breen.[196][197]

According to an account published by H.A. Wise, in 1847 Jean Baptiste Trudeau, one of George Donner's hired drivers boasted somewhat of his own heroism, but also spoke in lurid detail of eating Jacob Donner, and asserted that he had eaten a baby raw.[198] Many years later, Trudeau met Eliza Donner Houghton and denied ever cannibalizing anyone. He reiterated that this denial in an interview with a St. Louis newspaper in 1891, when he was 60 years old. Houghton and the other Donner children were fond of Trudeau, and he of them, in spite of their circumstances and the fact that he eventually left Tamsen Donner alone. Author George Stewart considers Trudeau's accounting to Wise more accurate than what he told Houghton in 1884, and asserted that he deserted the Donners.[199] Kristin Johnson, however, attributes Trudeau's interview with Wise to be a result of "common adolescent desires to be the center of attention and to shock one's elders"; after he had lived many more years he reconsidered his statements so as not to upset Houghton.[200] Historians Joseph King and Jack Steed call Stewart's characterization of Trudeau's actions as desertion "extravagant moralism", particularly because all members of the party were forced to make difficult choices.[201] Ethan Rarick echoed this by writing, "... more than the gleaming heroism or sullied villainy, the Donner Party is a story of hard decisions that were neither heroic nor villainous".[202]

See also

Notes

- ^ There are no written records of native tribes having crossed the desert, nor did the emigrants mention any trails in this region. (Rarick, p. 69.)

- ^ Rarick lists Keyes as 70 years old.

- ^ Tamsen Donner's letters were printed in the Springfield Journal in 1846. (McGlashan, p. 24.)

- ^ At Fort Laramie, Reed met an old friend named James Clyman who was coming from California. Clyman warned Reed not to take the Hastings Cutoff, telling him that wagons would not be able to make it and Hastings' information was inaccurate. (Rarick, p. 47.) J. Quinn Thornton, in his book From Oregon and California in 1848 traveled part of the way with Donner and Reed and declared Hastings the "Baron Munchausen of travelers in these countries". (Johnson, p. 20.)

- ^ While Hastings was otherwise occupied, his guides had led the Harlan-Young Party through Weber Canyon, which was not the route Hastings had intended to take. (Rarick, p. 61.)

- ^ Less than a year later, Mormon emigrants took the same route, also having to clear the trail, but spending much less time doing so. It has since been named Emigration Canyon. (Johnson, p. 28.)

- ^ In 1986 a team of archaeologists attempted to cross the same stretch of desert at the same time of year in four-wheel drive trucks and were unable to do so. (Rarick, p. 71.)

- ^ Reed's account states that many of the travelers lost cattle and were trying to locate them, although some of the other members thought they were looking for his cattle. (Rarick, p. 74)(Reed's self-penned "The Snow-Bound, Starved Emigrants of 1846 Statement by Mr. Reed, One of the Donner Company" in Johnson, p. 190.) This location has since been named Donner Spring, and is at the base of Pilot Peak. (Johnson, p. 31.)

- ^ The pass Hastings had used earlier that year was unsuitable for wagons, and he was searching for one that could be more easily traversed. (Rarick, p. 77.)

- ^ Reed wrote an account of the events of the Donner Party in 1871 in which he omitted any reference to his killing Snyder, although his daughter Virginia described it in a letter home written in May 1847, which was heavily edited by Reed. In Reed's 1871 account, he left the group to check on Stanton and McCutcheon. (Johnson p. 191.)

- ^ The cabins were built by three members of another group of emigrants known as the Stevens Party, specifically by Joseph Foster, Allen Stevens, and Moses Schallenberger in November 1844. (Hardesty, pp. 49–50.) Virginia Reed later married a member of this party named John Murphy, unrelated to the Murphy family who was associated with the Donner Party. (Johnson, p. 262.)

- ^ William Graves later wrote to Charles McGlashan that Sarah Fosdick and Mary Graves were concerned that Eddy was leading Mary away to kill her for food. (Johnson, p. 61.)

- ^ This drawing is inaccurate in several respects: the cabins were spread so far apart that Patrick Breen in his diary came to call inhabitants of other cabins "strangers" whose visits were rare. This scene furthermore shows a great deal of activity and livestock, when the emigrants were weakened already by low rations and livestock began to die almost immediately. It also neglects to include the snow that met the emigrants from the day they arrived.

- ^ Woodworth's role has been disputed by historians. Some of the survivors considered him a braggart and incompetent, but his role has since been viewed by historians as one more of planning and logistics. It is possible that Reed misunderstood that Woodworth was not going to go over the mountains himself, but would stay in Bear Valley and coordinate relief efforts there. (King, pp. 87–89.)(Rarick, p. 212.) Woodworth told Mrs. Breen after she arrived safely out of the mountains that she could thank him for her deliverance. According to William Graves, she responded, "'Thank you I thank no boddy but God and Stark and the Vergin Mary' [sic].... Putting Stark second best and I think he deserved it." (Johnson, p. 226.)

- ^ Mrs. Murphy temporarily recovered from her starvation-induced stupor after Keseberg took young George Foster—Murphy's grandson—to bed with him and announced in the morning the boy was dead. Murphy accused Keseberg of strangling the child. (Stewart, p. 248.)

- ^ Virginia Reed was an inconsistent speller and the letter is full of grammar, punctuation and spelling mistakes. It was printed in various forms at least five times and photographed in part. Stewart reprinted the letter with the original spelling and punctuation, but amended it to ensure the reader could understand what the girl was trying to say. The representation here is similar to Stewart's, with spelling and punctuation improvements. (Stewart, pp. 348–354.)

Citations

- ^ McGlashan, p. 16.

- ^ Stewart, p. 271.

- ^ Enright, John Shea (December 1954). "The Breens of San Juan Bautista: With a Calendar of Family Papers", California Historical Society Quarterly 33 (4) pp. 349–359.

- ^ Rarick, p. 11.

- ^ Rarick, p. 37.

- ^ Rarick, p. 10.

- ^ Rarick, pp. 18, 24, 45.

- ^ Rarick, p. 48.

- ^ Rarick, p. 45.

- ^ Rarick, pp. 46, 79.

- ^ a b Rarick, p. 47.

- ^ a b Rarick, p. 69.

- ^ Rarick, p. 105.

- ^ Rarick, p. 106.

- ^ a b Rarick, p. 17.

- ^ Waggoner, W. W. (December 1931). "The Donner Party and Relief Hill", California Historical Society Quarterly 10 (4) pp. 346–352.

- ^ a b Rarick, p. 18.

- ^ Rarick, p. 8

- ^ Stewart, p. 19.

- ^ a b Johnson, p. 181.

- ^ a b Rarick, p. 20.

- ^ Rarick, p. 23.

- ^ Rarick, p. 30.

- ^ Stewart, p. 26.

- ^ Stewart, p. 19–20.

- ^ Rarick, p. 50–52.

- ^ Rarick, p. 33.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Rarick, p. 47.

- ^ Johnson, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Andrews, Thomas F. (April 1973). "Lansford W. Hastings and the Promotion of the Great Salt Lake Cutoff: A Reappraisal", The Western Historical Quarterly 4 (2) pp. 133–150.

- ^ Stewart, p. 14.

- ^ Stewart, p. 16–18.

- ^ Rarick, p. 56.

- ^ Stewart, p. 25–27.

- ^ Rarick, p. 58.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Johnson, p. 22.

- ^ Stewart, p. 28.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 31–35.

- ^ Rarick, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Rarick, p. 64–65.

- ^ Rarick, pp. 67–68, Johnson, p. 25.

- ^ Rarick, p. 68.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 36–39.

- ^ Rarick, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b Stewart, pp. 40–44.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 44–50.

- ^ Rarick, pp, 72–74.

- ^ Rarick, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 50–53.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 54–58.

- ^ a b Rarick, pp. 78–81.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 54–58.

- ^ Rarick, p. 82.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 59–65.

- ^ Johnson, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Rarick, pp. 83–86.

- ^ Downey, Fairfax (Autumn 1939). "Epic of Endurance", The North American Review 248 (1) pp. 140–150.

- ^ Stewart, p. 66.

- ^ Rarick, p. 74.

- ^ Rarick, p. 87.

- ^ Johnson, p. 38–39.

- ^ Rarick, pp. 87–89.

- ^ Rarick, p. 89.

- ^ Rarick, p. 95.

- ^ Rarick, p. 98.

- ^ a b Stewart, pp. 67–74.

- ^ quote from Rarick, p. 98. Details given in Stewart, pp. 75–79.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 75–79.

- ^ Rarick, p. 91.

- ^ Rarick, p. 101.

- ^ Johnson, p. 43.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Rarick, p. 108.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 84–87.

- ^ Johnson, p. 193.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 95–100.

- ^ McGlashan, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Rarick, p. 112.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 101–104.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 105–107.

- ^ Hardesty, p. 60.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Johnson, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d "Roster of the Donner Party" in Johnson, pp. 294–298.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 110–115.

- ^ Johnson, p. 46.

- ^ McGlashan pp. 66–67.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 116–121.

- ^ Johnson, p. 49, McGlashan, p. 66.

- ^ a b McGlashan, p. 67.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 122–125.

- ^ a b Rarick, p. 136.

- ^ Thornton, J. Quinn, excerpt from Oregon and California in 1848 (1849), published in Johnson, p. 52.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 126–130.

- ^ Rarick, p. 137.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 131–133.

- ^ Thornton, J. Quinn, excerpt from Oregon and California in 1848 (1849), published in Johnson, p. 53.

- ^ Thornton, J. Quinn, excerpt from Oregon and California in 1848 (1849), published in Johnson, p. 55.

- ^ Thornton, J. Quinn, excerpt from Oregon and California in 1848 (1849), published in Johnson, p. 56.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 134–141.

- ^ Rarick, p. 142.

- ^ Thornton, J. Quinn, excerpt from Oregon and California in 1848 (1849), published in Johnson, p. 60.

- ^ Johnson, p. 62.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 142–148.

- ^ Johnson, p. 63–64.

- ^ Stewart, p. 149.

- ^ Rarick, p. 142.

- ^ Rarick, p. 145.

- ^ McGlashan, p. 90.

- ^ Rarick, p. 146.

- ^ Johnson, p. 40. See also McGlashan letter from Leanna Donner, 1879.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 160–167.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 168–175.

- ^ Rarick, pp. 148–150.

- ^ Rarick, p. 152.

- ^ Thornton, J. Quinn, excerpt from Oregon and California in 1848 (1849), published in Johnson, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 150–159.

- ^ Rarick, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 176–189.

- ^ Rarick, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Stewart, p. 191.

- ^ Rarick, p. 173.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 190–196.

- ^ Rarick, p. 170.

- ^ Rarick, p. 171.

- ^ Stewart, p. 198.

- ^ Rarick, p. 174.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 197–203.

- ^ Rarick, p. 178.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 204–206.

- ^ Rarick, p. 187.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Rarick, p. 191.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 215–219.

- ^ Rarick, p. 195.

- ^ Stewart, pp. 220–230.