Punched card

A punched card[2] (or Hollerith card or IBM card), is a piece of stiff paper that contains digital information represented by the presence or absence of holes in predefined positions. Now almost an obsolete recording medium, punched cards were widely used throughout the 19th century for controlling textile looms and in the late 19th and early 20th century for operating fairground organs and related instruments. They were used through the 20th century in unit record machines for input, processing, and data storage. Early digital computers used punched cards, often prepared using keypunch machines, as the primary medium for input of both computer programs and data. Some voting machines use punched cards.

History

Punched cards were first used around 1725 by Basile Bouchon and Jean-Baptiste Falcon as a more robust form of the perforated paper rolls then in use for controlling textile looms in France. This technique was greatly improved by Joseph Marie Jacquard in his Jacquard loom in 1801.

Semen Korsakov was reputedly the first to use the punched cards in informatics for information store and search. Korsakov announced his new method and machines in September 1832, and rather than seeking patents offered the machines for public use.[3]

Charles Babbage proposed the use of "Number Cards", pierced with certain holes and stand opposite levers connected with a set of figure wheels ... advanced they push in those levers opposite to which there are no holes on the card and thus transfer that number ... in his description of the Calculating Engine's Store [4].

Herman Hollerith invented the recording of data on a medium that could then be read by a machine. Prior uses of machine readable media, such as those above (other than Korsakov), had been for control, not data. "After some initial trials with paper tape, he settled on punched cards..."[5], developing punched card data processing technology for the 1890 US census. He founded the Tabulating Machine Company (1896) which was one of four companies that merged to form Computing Tabulating Recording Corporation (CTR), later renamed IBM. IBM manufactured and marketed a variety of unit record machines for creating, sorting, and tabulating punched cards, even after expanding into electronic computers in the late 1950s. IBM developed punched card technology into a powerful tool for business data-processing and produced an extensive line of general purpose unit record machines. By 1950, the IBM card and IBM unit record machines had become ubiquitous in industry and government. "Do not fold, spindle or mutilate," a generalized version of the warning that appeared on some punched cards (generally on those distributed as paper documents to be later returned for further machine processing, checks for example), became a motto for the post-World War II era (even though many people had no idea what spindle meant). [6]

From the 1900s, into the 1950s, punched cards were the primary medium for data entry, data storage, and processing in institutional computing. According to the IBM Archives: "By 1937... IBM had 32 presses at work in Endicott, N.Y., printing, cutting and stacking five to 10 million punched cards every day."[7] Punched cards were even used as legal documents, such as U.S. Government checks[8] and savings bonds. During the 1960s, the punched card was gradually replaced as the primary means for data storage by magnetic tape, as better, more capable computers became available. Punched cards were still commonly used for data entry and programming until the mid-1970s when the combination of lower cost magnetic disk storage, and affordable interactive terminals on less expensive minicomputers made punched cards obsolete for this role as well.[9] However, their influence lives on through many standard conventions and file formats. The terminals that replaced the punched cards, the IBM 3270 for example, displayed 80 columns of text in text mode, for compatibility with existing software. Some programs still operate on the convention of 80 text columns, although fewer and fewer do as newer systems employ graphical user interfaces with variable-width type fonts.

Today punched cards are mostly obsolete and replaced with other storage methods, except for a few legacy systems and specialized applications.

Card formats

The early applications of punched cards all used specifically designed card layouts. It wasn't until around 1928 that punched cards and machines were made "general purpose". The rectangular, round, or oval bits of paper punched out are called chad (recently, chads) or chips (in IBM usage). Multi-character data, such as words or large numbers, were stored in adjacent card columns known as fields. A group of cards is called a deck. One upper corner of a card was usually cut so that cards not oriented correctly, or cards with different corner cuts, could be easily identified. Cards were commonly printed so that the row and column position of a punch could be identified. For some applications printing might have included fields, named and marked by vertical lines, logos, and more.

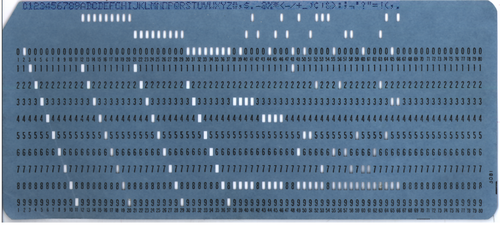

One of the most common printed punched cards was the IBM 5081. Indeed, it was so common that other card vendors used the same number (see image at right) and even users knew its number.

Hollerith's punched card formats

Herman Hollerith was awarded a series of patents[10] in 1889 for mechanical tabulating machines. These patents described both paper tape and rectangular cards as possible recording media. The card shown in U.S. patent 395,781 was preprinted with a template and had holes arranged close to the edges so they could be reached by a railroad conductor's ticket punch, with the center reserved for written descriptions. Hollerith was originally inspired by railroad tickets that let the conductor encode a rough description of the passenger:

- "I was traveling in the West and I had a ticket with what I think was called a punch photograph...the conductor...punched out a description of the individual, as light hair, dark eyes, large nose, etc. So you see, I only made a punch photograph of each person."[11]

Use of the ticket punch proved tiring and error prone, so Hollerith invented a pantograph "keyboard punch" that allowed the entire card area to be used. It also eliminated the need for a printed template on each card, instead a master template was used at the punch; a printed reading card could be placed under a card that was to be read manually. Hollerith envisioned a number of card sizes. In an article he wrote describing his proposed system for tabulating the 1890 U.S. Census, Hollerith suggested a card 3 inches by 5½ inches of Manila stock "would be sufficient to answer all ordinary purposes."[12]

The cards used in the 1890 census had round holes, 12 rows and 24 columns. A census card and reading board for these cards can be seen at the Columbia University Computing History site.[13] At some point, 3.25 by 7.375 inches (3¼" x 7⅜") became the standard card size, a bit larger than the United States one-dollar bill of the time (the dollar was changed to its current size in 1929). The Columbia site says Hollerith took advantage of available boxes designed to transport paper currency.

Hollerith's original system used an ad-hoc coding system for each application, with groups of holes assigned specific meanings, e.g. sex or marital status. His tabulating machine had 40 counters, each with a dial divided into 100 divisions, with two indicator hands; one which stepped one unit with each counting pulse, the other which advanced one unit every time the other dial made a complete revolution. This arrangement allowed a count up to 10,000. During a given tabulating run, each counter was typically assigned a specific hole. Hollerith also used relay logic to allow counts of combination of holes, e.g. to count married females.[12]

Later designs standardized the coding, with 12 rows, where the lower ten rows coded digits 0 through 9. This allowed groups of holes to represent numbers that could be added, instead of simply counting units. Hollerith's 45 column punched cards are illustrated in Comrie's The application of the Hollerith Tabulating Machine to Brown's Tables of the Moon.[14][15]

IBM 80 column punched card format

This IBM card format, designed in 1928,[16] had rectangular holes, 80 columns with 12 punch locations each, one character to each column. Card size was exactly 7-3/8 inch by 3-1/4 inch (187.325 by 82.55 mm). The cards were made of smooth stock, 0.007 inch (0.178 mm) thick. There are about 143 cards to the inch. In 1964, IBM changed from square to round corners.[17]

The lower ten positions represented (from top to bottom) the digits 0 through 9. The top two positions of a column were called zone punches, 12 (top) and 11. Originally only numeric information was punched, with 1 punch per column indicating the digit. Signs could be added to a field by overpunching the least significant digit with a zone punch: 12 for plus and 11 for minus. Zone punches had other uses in processing as well, such as indicating a master record.

______________________________________________

/&-0123456789ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQR/STUVWXYZ

Y / x xxxxxxxxx

X| x xxxxxxxxx

0| x xxxxxxxxx

1| x x x x

2| x x x x

3| x x x x

4| x x x x

5| x x x x

6| x x x x

7| x x x x

8| x x x x

9| x x x x

|________________________________________________

Reference:[18] Note: The Y and X zones were also called the 12 and 11 zones, respectively.

Later, multiple punches were introduced for upper-case letters and special characters[19]. A letter had 2 punches (zone [12,11,0] + digit [1-9]); a special character had 3 punches (zone [12,11,0] + digit [2-4] + 8). With these changes, the information represented in a column by a combination of zones [12, 11] and digits [1-9] was dependent on the use of that column. For example the combination "12-1" was the letter "A" in an alphabetic column, a plus signed digit "1" in a signed numeric column, or an unsigned digit "1" in a column where the "12" had some other use. The introduction of EBCDIC in 1964 allowed columns with as many as 6 punches (zones [12,11,0,8,9] + digit [1-7]). IBM and other manufacturers used many different 80-column card character encodings.[20][21]

For some computer applications, binary formats were used, where each hole represented a single binary digit (or "bit"), every column (or row) was treated as a simple bitfield, and every combination of holes was permitted. For example, the IBM 711 card reader used with the 704/709/7090/7094 series scientific computers treated every row as two 36-bit words. (The specific 72 columns used were selectable using a control panel, which was almost always wired to select columns 1-72, ignoring the last 8 columns.) Other computers, such as the IBM 1130 or System/360, used every column. The IBM 1402 could be used in "column binary" mode, which stored two characters in every column, or one 36-bit word in three columns.

As a prank, in binary mode, cards could be punched where every possible punch position had a hole. Such "lace cards" lacked structural strength, and would frequently buckle and jam inside the machine.

The 80-column card format dominated the industry, becoming known as just IBM cards, even though other companies made cards and equipment to process them.

Mark sense cards

- Mark sense (Electrographic) cards, developed by Reynold B. Johnson at IBM, had printed ovals that could be marked with a special electrographic pencil. Cards would typically be punched with some initial information, such as the name and location of an inventory item. Information to be added, such as quantity of the item on hand, would be marked in the ovals. Card punches with an option to detect mark sense cards could then punch the corresponding information into the card.

Aperture cards

- Aperture cards have a cut-out hole on the right side of the punched card. A 35 mm microfilm chip containing a microform image is mounted in the hole. Aperture cards are used for engineering drawings from all engineering disciplines. Information about the drawing, for example the drawing number, is typically punched and printed on the remainder of the card. Aperture cards have some advantages over digital systems for archival purposes.[22]

IBM 51 column punched card format

This IBM card format was a shortened 80-column card; the shortening sometimes accomplished by tearing off, at a perforation, a stub from an 80 column card. These cards were used in some retail and inventory applications.

IBM Port-A-Punch

According to the IBM Archive: IBM's Supplies Division introduced the Port-A-Punch in 1958 as a fast, accurate means of manually punching holes in specially scored IBM punched cards. Designed to fit in the pocket, Port-A-Punch made it possible to create punched card documents anywhere. The product was intended for "on-the-spot" recording operations—such as physical inventories, job tickets and statistical surveys—because it eliminated the need for preliminary writing or typing of source documents..[23] Unfortunately, the resulting holes were "furry" and sometimes caused problems with the equipment used to read the cards.

A pre-perforated card was used for Monash University's MIDITRAN Language; and the cards would sometimes lose chads in the reader, changing the contents of the student's data or program deck.

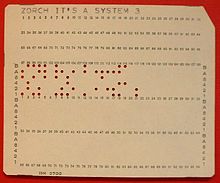

IBM 96 column punched card format

In the early 1970s IBM introduced a new, smaller, round-hole, 96-column card format along with the IBM System/3 computer.[24] IBM 5496 Data Recorder, a keypunch machine with print and verify functions, and IBM 5486 Card Sorter were made for these 96-column cards.

These cards had tiny (1 mm), circular holes, smaller than those in paper tape. Data was stored in six-bit binary-coded decimal code, with three rows of 32 characters each, or 8-bit EBCDIC. In this format, each column of the top tiers are combined with 2 punch rows from the bottom tier to form an 8-bit byte, and the middle tier is combined with 2 more punch rows, so that each card contains 64 bytes of 8-bit-per-byte binary data. See Winter, Dik T. "96-column Punched Card Code". Retrieved December 23, 2008. {{cite web}}: Unknown parameter |dateformat= ignored (help)

Powers/Remington Rand UNIVAC card formats

The Powers/Remington Rand card format was initially the same as Holleriths; 45 columns and round holes. In 1930 Remington-Rand leap-frogged IBM's 1928 introduced 80 column format by coding two characters in each of the 45 columns - producing what is now commonly called the 90-column card[25]. For its character codings, see Winter, Dik T. "90-column Punched Card Code". Retrieved October 20, 2006. {{cite web}}: Unknown parameter |dateformat= ignored (help)

IBM punched card manufacturing

IBM's Fred M. Carroll[26] developed a series of rotary type presses that were used to produce the well-known standard tabulating cards, including a 1921 model that operated at 400 cards per minute (cpm). Later, he developed a completely different press capable of operating at speeds in excess of 800 cpm, and it was introduced in 1936.[7][27] Carroll's high-speed press, containing a printing cylinder, revolutionized the manufacture of punched tabulating cards.[28] It is estimated that between 1930 and 1950, the Carroll press accounted for as much as 25 per cent of the company's profits[29]

Discarded printing plates from these card presses, each printing plate the size of an IBM card and formed into a cylinder, often found use as desk pen/pencil holders, and even today are collectable IBM artifacts (every card layout[30] had its own printing plate).

IBM initially required that its customers use only IBM manufactured cards with IBM machines, which were leased, not sold. IBM viewed its business as providing a service and that the cards were part of the machine. In 1932 the government took IBM to court on this issue, IBM fought all the way to the Supreme Court and lost; the court ruling that IBM could only set card specifications. In another case, heard in 1955, IBM signed a consent decree requiring, amongst other things, that IBM would by 1962 have no more than one-half of the punched card manufacturing capacity in the United States. Tom Watson Jr.'s decision to sign this decree, where IBM saw the punched card provisions as the most significant point, completed the transfer of power to him from Thomas Watson, Sr.[29]

Cultural impact

While punched cards have not been widely used for a generation, the impact was so great for most of the 20th century that they still appear from time to time in popular culture.

For example:

- Sculptor Maya Lin designed a controversial public art installation at Ohio University that looks like a punched card from the air.[31]

- Do Not Fold, Bend, Spindle or Mutilate: Computer Punch Card Art - a mail art exhibit by the Washington Pavilion in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

- The Red McCombs School of Business at the University of Texas at Austin has artistic representations of punched cards decorating its exterior walls.

- At the University of Wisconsin - Madison, the Engineering Research Building's exterior windows were modeled after a punched card layout, during its construction in 1966. [1]

- In the Simpsons episode Much Apu About Nothing, Apu showed Bart his Ph.D. thesis, the world's first computer tic-tac-toe game, stored in a box full of punched cards.

A legacy of the 80 column punched card format is that most character-based terminals display 80 characters per row. Even now, the default size for character interfaces such as the command prompt in Windows remains set at 80 columns. Some file formats, such as FITS, still use 80-character card images.

Standards

- ANSI INCITS 21-1967 (R2002), Rectangular Holes in Twelve-Row Punched Cards (formerly ANSI X3.21-1967 (R1997)) Specifies the size and location of rectangular holes in twelve-row 3-1/4 inch wide punched cards.

- ANSI X3.11 - 1990 American National Standard Specifications for General Purpose Paper Cards for Information Processing

- ANSI X3.26 - 1980/R1991) Hollerith Punched Card Code

- ISO 1681:1973 Information processing - Unpunched paper cards - Specification

- ISO 6586:1980 Data processing - Implementation of the ISO 7- bit and 8- bit coded character sets on punched cards. Defines ISO 7-bit and 8-bit character sets on punched cards as well as the representation of 7-bit and 8-bit combinations on 12-row punched cards. Derived from, and compatible with, the Hollerith Code, ensuring compatibility with existing punched card files.

Card handling equipment

Creation and processing of punched cards was handled by a variety of devices, including:

See also

- Card image

- Computer programming in the punch card era

- History of computing hardware

- Paper data storage

Notes and References

- ^ Truesdell, Leon E. (1965). The Development of Punch Card Tabulation in the Bureau of the Census: 1890-1940. US GPO.

- ^ The verb "punch" when used as a verbal adjective is called a participle. When combined with the noun "card", "punch" is a passive (or past) participle, describing a noun that has been the object of the verb's action and thus is suffixed with "ed", forming the name "punched card". Similar to the way the verbal adjective "play", used as an active (or present) participle and thus suffixed with "ing", is combined with "card" forming the name "playing card". Note that a name is not a description of the current state of the object: a punched card may never have been punched, a playing card may never have been played with. In some texts repetitive use of the terms "punched card" or "punched cards" is replaced with simply "card" or"cards". Deviant terms such as "punch card" or "punchcard" have been occasionally used in the now more than 100 years of data processing literature.

- ^ Semen Korsakov's inventions, Cybernetics Dept. of MEPhI Template:Ru icon

- ^ Babbage, Charles (26 Dec. 1837). On the Mathematical Powers of the Calculating Engine.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Columbia University Computing History - Herman Hollerith

- ^ History of the punch card

- ^ a b IBM Archive: Endicott card manufacturing

- ^ Lubar, Steven (1993). InfoCulture: The Smithsonian Book of Information Age Inventions. Houghton Mifflin. p. 302. ISBN 0-395-57042-5.

- ^ Aspray (ed.), W. (1990). Computing before Computers. Iowa State University Press. p. 151. ISBN 0-8138-0047-1.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ U.S. patent 395,781, U.S. patent 395,782, U.S. patent 395,783

- ^ http://www.history.rochester.edu/steam/hollerith/cards.htm

- ^ a b [-245-] An Electric Tabulating System, The Quarterly, Columbia University School of Mines, Vol.X No.16 (April 1889)

- ^ Columbia University Computing History: Hollerith 1890 Census Tabulator

- ^ Plates from: Comrie, L.J. (1932). "The application of the Hollerith Tabulating Machine to Brown's Tables of the Moon". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 92 (7): 694–707.

- ^ Comrie, L.J. (1932). "The application of the Hollerith tabulating machine to Brown's tables of the moon". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 92 (7): 694–707. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ^ IBM Archive: 1928.

- ^ IBM Archive: Old/New-Cards.

- ^ Punched Card Codes

- ^ Special characters are non-alphabetic, non-numeric, such as "&#,$.-/@%*?"

- ^

Winter, Dik T. "80-column Punched Card Codes". Retrieved October 20, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^

Jones, Douglas W. "Punched Card Codes". Retrieved February 20, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ LoTurco, Ed (January 2004). "The Engineering Aperture Card: Still Active, Still Vital" (PDF). EDM Consultants. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ IBM Archive: Port-A-Punch

- ^ IBM Field Engineering Announcement: IBM System/3

- ^ Aspray (ed.). op. cit. p. 142.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ IBM Archives/Business Machines: Fred M. Carroll

- ^ IBM Archives: Fred M. Carroll

- ^ IBM Archives: (IBM) Carroll Press

- ^ a b Belden, Thomas (1962). The Lengthening Shadow: The Life of Thomas J. Watson. Little, Brown & Company.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ IBM Archives:1939 Layout department

- ^ http://www.mayalin.org

External links

- Lubar, Steve (1991). ""Do not fold, spindle or mutilate": A cultural history of the punch card".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Jones, Douglas W. "Punched Cards". Retrieved October 20, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) (Collection shows examples of left, right, and no corner cuts.) - VintageTech - a U.S. company that converts punched cards to conventional media

- Dyson, George (1999). "The Undead". Wired magazine. 7 (3). Retrieved October 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) article about modern-day use of punched cards - Williams, Robert V. (2002). "Punched Cards: A Brief Tutorial". IEEE Annals - Web extra. Retrieved 2006-10-30.

- UNIVAC Punch Card Gallery (Shows examples of both left and right corner cuts.)

- Cardamation - a U.S. company still supplying punched card equipment and supplies as of 2008[update].

- An Emulator for Punched cards

- Fierheller, George A. (2006). Do not fold, spindle or mutilate: the "hole" story of punched cards. Stewart Pub. ISBN 1-894183-86-X. An accessible book of recollections (sometimes with errors), with photographs and descriptions of many unit record machines.

- Brian De Palma (Director) (1961). 660124: The Story of an IBM Card (Film).

- Povarov G.N. Semen Nikolayevich Korsakov. Machines for the Comparison of Philosophical Ideas. In: Trogemann, Georg; Ernst, Wolfgang and Nitussov, Alexander, Computing in Russia: The History of Computer Devices and Information Technology Revealed (pp 47–49), Verlag, 2001. Translated by Alexander Y. Nitussov. ISBN 3-528-05757-2, 9783528057572

- Korsakov S.N. A Depiction of a New Research Method, Using Machines which Compare Ideas, Ed. by Alexander Mikhailov, MEPhI, 2009 Template:Ru icon

This article is based on material taken from the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing prior to 1 November 2008 and incorporated under the "relicensing" terms of the GFDL, version 1.3 or later.