Omnipotence paradox

The omnipotence paradox arises from the attempt to apply logic to the concept of an omnipotent being. A well-known formulation of the paradox is:

- Could an omnipotent being create a stone so heavy that even that being could not lift it?

The crux of the paradox is whether an omnipotent being is able to limit its own omnipotence. Since the Middle Ages, philosophers have phrased the paradox in a variety of ways, of which the "heavy stone" is only one (see below).

Some philosophers argue that the omnipotence paradox is proof that an omnipotent being cannot exist. Others argue that the paradox only arises from a misunderstanding or mischaracterization of the concept of omnipotence. Finally, some philosophers consider the question to be a false dilemma, because it avoids the possibility of varying degrees of omnipotence (Haeckel).

The paradox as argument against omnipotence

It is possible to construe the paradox as an argument against God's omnipotence, as in the following restatement by Stephan Torre [1]:

- Either God can create a stone that he cannot lift, or God cannot create a stone that he cannot lift.

- If God can create a stone that he cannot lift, then necessarily, there is at least one task that God cannot perform (namely lift the stone in question).

- If God cannot create a stone that he cannot lift, then, necessarily, there is at least one task that he cannot perform (namely create the stone in question).

- Hence there is at least one task that God cannot perform.

- If God is an omnipotent being, then he can perform any task.

- Therefore, God is not omnipotent.

Philosophical views of "omnipotence"

The definition of omnipotence literally is "all-powerful," or "able to do anything," but this raises a question: Does "anything" include things that are logically impossible (things that would result in a contradiction)?

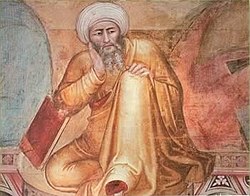

Averroës was of the opinion that God cannot do the logically impossible. He was one of the first philosophers to propose the omnipotence paradox, though in a different form. His question was whether God could create a triangle with internal angles that did not add up to 180 degrees. (Note that invoking non-Euclidean geometry does not resolve the crux of this paradox, since one can use simple arithmetic to express the logical impossibility: "Can God make it the case that 1 + 1 = 3?")

Possible Solutions to the Paradox

One possible solution to the omnipotence paradox is as follows:

- An omnipotent being creates a stone that even it cannot lift it.

- The omnipotent being then becomes able to lift the stone, thus retaining its omnipotence.

Descartes' view was that an omnipotent being can do the logically impossible. He thus "solved" the paradox as follows:

- An omnipotent being can do the logically impossible.

- The omnipotent being creates a stone which it cannot lift.

- The omnipotent being then lifts the stone.

The fact that #2 and #3 conflict is not a problem if the being can do the logically impossible. If the paradox is "solved" this way, though, it appears to be at the expense of logical consistency.

Is an omnipotent being automatically omniscient?

-Incomplete-

Historical repercussions

After the Reconquista, translations of Averroës' work, and those of other Arab scientific and philosophical writers – many of them in turn translations of Ancient Greek material – entered European intellectual society. When Averroës's conundrum reached Paris, it became part of a controversy which led to the University's theology students going on strike for six years, and Averroës was condemned by Bishop Tempier. (For more information on the Averroës controversy, see James Burke's The Day the Universe Changed, episode 2.)

Mainstream Catholic theology eventually reconciled itself to the Greek and Arabic material the Reconquista made available, thanks in large part to Thomas Aquinas, whose Summa Theologica affirmed the notion that God could not defy logic. In this respect, Aquinas follows the thinking of Maimonides, the 12th-century Jewish philosopher and physician, who makes the same proposition in his Guide for the Perplexed. (Maimonides was an adherent of negative theology, a discipline which holds that one can only describe God via negations.)

Pop culture references

- In the television show Star Trek: The Next Generation, the entity known as "Q" is omnipotent, and the paradoxical consequences are explored in a number of episodes, typically in a humorous vein.

- In the television show The Simpsons, Homer Simpson asks his neighbor Ned Flanders, "Can Jesus microwave a burrito so hot that He Himself could not eat it?" (episode "Weekend at Burnsie's").

- In the television show Babylon 5, two characters talk about the paradox:

- Franklin: "Can God make a rock so big, that even he can't lift it?"

- G'kar: "Yes, I've heard it, but...."

- Franklin: "What if that is the wrong question? Wonder if the right question is, Can God create a puzzle so difficult, a riddle so complex, that even he can't solve it? What if that's us? Maybe a problem like this is God's way of doing to us a little of what we do to him."

- In his nightclub routine, George Carlin used to mention the "heavy stone" question as one that mischievous boys in his neighborhood would ask their priest.[2]

Related paradoxes

- Peter Suber discusses the paradox of legal omnipotence — defined as the ability of a legal system to make any law at any time — in The Paradox of Self-Amendment: A Study of Law, Logic, Omnipotence, and Change [3], taking up such questions as how a legal system can amend itself, and whether an omnipotent legal system can terminate its own omnipotence. Suber created the game Nomic in part to explore such questions.

- The irresistible force paradox asks What happens when an irresistible force meets an immovable object? A response to this paradox is that if a force is irresistible, then by definition there is no truly immovable object; conversely, if an immovable object were to exist, then no force could be defined as being truly irresistible.

See also

References

- External links in the following were last verified 16 November 2005.

- Haeckel, Ernst. The Riddle of the Universe. Harper and Brothers, 1900.

- Hoffman, Joshua, Rosenkrantz, Gary. "Omnipotence" The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2002 Edition). Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Wierenga, Edward. "Omnipotence" The Nature of God: An Inquiry into Divine Attributes. Cornell University Press, 1989.

- Gleick, James. Genius. Pantheon, 1992. ISBN 0-679-40836-3.

- Morris Telford's Salopian Odyssey (famously references the paradox)

- Burke, James. The Day the Universe Changed. Little, Brown; 1995 (paperback edition). ISBN 0-316-11704-8.

- Allen, Ethan. Reason: The Only Oracle of Man. J.P. Mendum, Cornill; 1854. Originally published 1784, available online.