Things Fall Apart

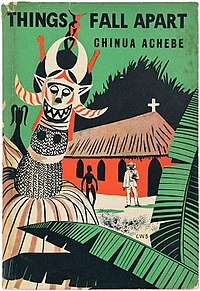

First paperback edition cover | |

| Author | Chinua Achebe |

|---|---|

| Original title | Things Fall Apart |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | William Heinemann Ltd. |

Publication date | 1958 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

Published in English | 224 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| ISBN | 9780385474542 |

| Followed by | No Longer at Ease |

Things Fall Apart is a 1958 English language novel by Nigerian author Chinua Achebe. It is a staple book in schools throughout Africa and widely read and studied in English-speaking countries around the world. It is seen as the archetypal modern African novel in English, and one of the first African novels written in English to receive global critical acclaim. The title of the novel comes from William Butler Yeats's poem "The Second Coming".[1] In 2009, Newsweek ranked Things Fall Apart #14 on its list of Top 100 Books: The Meta-List.[2]

The novel depicts the life of Okonkwo, a leader and local wrestling champion in Umuofia—one of a fictional group of nine villages in Nigeria, inhabited by the Igbo ethnic group. In addition it focuses on his three wives, his children, and the influences of British colonialism and Christian missionaries on his traditional Igbo (archaically "Ibo") community during the late nineteenth century.

Things Fall Apart was followed by a sequel, No Longer at Ease (1960), originally written as the second part of a larger work together with Things Fall Apart, and Arrow of God (1964), on a similar subject. Achebe states that his two later novels, A Man of the People (1966) and Anthills of the Savannah (1987), while not featuring Okonkwo's descendants and set in fictional African countries, are spiritual successors to the previous novels in chronicling African history.

Plot summary

Although Okonkwo's father was a lazy man who received no titles in his village, Okonkwo was a great man in his home of Umuofia, a group of nine villages in Nigeria. Okonkwo despised his father and does everything he can to be nothing like him. As a young man, Okonkwo began building his social status by defeating a great wrestler, propelling him into society's eye. He is hard-working and shows no weakness—emotional or otherwise—to anyone. Although brusque with his family and neighbors, he is wealthy, courageous, and powerful among his village. He is a leader of his village, and his place in that society is what he has striven for his entire life.

Because of his great esteem in the village, Okonkwo is selected by the elders to be the guardian of Ikemefuna, a boy taken prisoner by the village as a peace settlement between two villages. Ikemefuna is to stay with Okonkwo until the Oracle instructs the elders on what to do with the boy. For three years the boy lives with Okonkwo's family and he grows fond of him, he even considers Okonkwo his father. Then the elders decide that the boy must be killed, and the oldest man in the village warns Okonkwo to have nothing to do with the murder because it would be like killing his own child. Rather than seem weak and feminine to the other men of the village, Okonkwo helps to kill the boy despite the warning from the old man. In fact, Okonkwo himself strikes the killing blow as Ikemefuna begs him for protection.

Shortly after Ikemefuna's death, things begin to go wrong for Okonkwo and when he accidentally kills someone at a ritual funeral ceremony, he and his family are sent into exile for seven years to appease the gods he has offended with the murder. While Okonkwo is away in exile, white men begin coming to Umuofia and they peacefully introduce their religion. As the number of converts increases, the foothold of the white people grows beyond their religion and a new government is introduced.

Okonkwo returns to his village after his exile to find it a changed place because of the presence of the white man. He and other tribal leaders try to reclaim their hold on their native land by destroying a local Christian church that has insulted their gods and religion. In return, the leader of the white government takes them prisoner and holds them for ransom for a short while, further humiliating and insulting the native leaders. The people of Umuofia finally gather for what could be a great uprising, and when some messengers of the white government try to stop their meeting, Okonkwo kills one of them. He realizes with despair that the people of Umuofia are not going to fight to protect themselves because they let the other messengers escape and so all is lost for the village. He also decides never to let the whites imprison him.

When the local leader of the white government comes to Okonkwo's house to take him to court, he finds that Okonkwo has hanged himself, ruining his great reputation as it is strictly against the custom of the Igbo to kill oneself.

Culture

Achebe depicts the Igbo as a people with great social institutions in accordance with their particular society, ie, wrestling, human sacrifice and suicide. Their culture is heavy in traditions and laws that focus on justice and fairness. The people are ruled not by a king or chief but by a kind of democracy, where the males meet and make decisions by consensus and in accordance to an "Oracle" that should be written down. It is the Europeans, who often talk of bringing democratic institutions to the rest of the world, that upset this system. Achebe emphasizes that high rank is attainable for all freeborn Igbo men – he attained his through fighting as opposed to reading or ploughing the land and growing herbal remedies, vegetation, rearing cattle, fowl etc.

He also depicts the injustices of Igbo society. No more or less than Victorian England of the same era, the Igbo are a patriarchal society. They also fear twins, who are to be abandoned immediately after birth and left to die of exposure. The novel attempts to repair some of the damage done by earlier European depictions of Africans. But this recuperation must necessarily come in the form of memory; by the time Achebe was born, the coming of the white man had already destroyed many aspects of indigenous culture and destructive belief patterns.

Characters

Okonkwo An influential clan leader in Umuofia. Since early childhood, Okonkwo’s embarrassment about his lazy, squandering, and effeminate father, Unoka, has driven him to succeed. Okonkwo’s hard work and prowess in war have earned him a position of high status in his clan, and he attains wealth sufficient to support three wives and their nine children. Okonkwo’s tragic flaw is that he is terrified of being weak or "womanly" like his father. As a result, he behaves rashly, bringing a great deal of trouble and sorrow upon himself and his family. He is a tragic character who not only brings suffering to himself but also to those around him.

Nwoye Okonkwo’s oldest son, who Okonkwo believes is weak and lazy. Okonkwo continually beats Nwoye, hoping to correct what he sees as flaws in his personality. Influenced by Ikemefuna, Nwoye begins to exhibit more masculine behavior, which pleases Okonkwo. However, he maintains doubts about some of the laws and rules of his village and eventually converts to Christianity, an act that Okonkwo criticizes as “effeminate.” Okonkwo believes that Nwoye is afflicted with the same weaknesses that his father, Unoka, possessed in abundance.

Ezinma The only child of Okonkwo’s second wife, Ekwefi. As the only one of Ekwefi’s ten children to survive past infancy, Ezinma is the center of her mother’s world. Their relationship is atypical—Ezinma calls Ekwefi by her name and is treated by her as an equal. Ezinma is also Okonkwo’s favorite child, for she understands him better than any of his other children. She reminds him of Ekwefi, who was the village beauty. Okonkwo rarely demonstrates his affection, however, because he fears that doing so would make him look weak. Furthermore, he wishes that Ezinma were a boy because she would have been the perfect son.

Ikemefuna A boy given to Okonkwo by a neighboring village. Ikemefuna lives in the hut of Okonkwo’s first wife and quickly becomes popular with Okonkwo’s children. He develops an especially close relationship with Nwoye, Okonkwo’s oldest son, who looks up to him. Okonkwo too becomes very fond of Ikemefuna, who calls him “father” and is a perfect clansman, but Okonkwo does not demonstrate his affection because he fears that doing so would make him look weak.

Mr. Brown The first white missionary to travel to Umuofia. Mr. Brown institutes a policy of compromise, understanding, and non-aggression between his flock and the clan. He even becomes friends with prominent clansmen and builds a school and a hospital in Umuofia. Unlike Reverend Smith, he attempts to appeal respectfully to the Igbo value system rather than harshly impose his religion on it.

Reverend James Smith The missionary who replaces Mr. Brown. Unlike Mr. Brown, Reverend Smith is uncompromising and strict. He demands that his converts reject all of their indigenous beliefs, and he shows no respect for indigenous customs or culture. He is the stereotypical white colonialist, and his behavior epitomizes the problems of colonialism. He intentionally provokes his congregation, inciting it to anger and even indirectly, through Enoch, encouraging some fairly serious transgressions.

Uchendu The younger brother of Okonkwo’s mother. Uchendu receives Okonkwo and his family warmly when they travel to Mbanta, and he advises Okonkwo to be grateful for the comfort that his motherland offers him lest he anger the dead—especially his mother, who is buried there. Uchendu himself has suffered—all but one of his six wives are dead and he has buried twenty-two children. He is a peaceful, compromising man and functions as a foil (a character whose emotions or actions highlight, by means of contrast, the emotions or actions of another character) to Okonkwo, who acts impetuously and without thinking.

The District Commissioner An authority figure in the white colonial government in Nigeria. The prototypical racist colonialist, the District Commissioner thinks that he understands everything about native African customs and cultures and he has no respect for them. He plans to work his experiences into an ethnographic study on local African tribes, the idea of which embodies his dehumanizing and reductive attitude toward race relations.

Unoka Okonkwo’s father, of whom Okonkwo has been ashamed since childhood. By the standards of the clan, Unoka was a coward and a spendthrift. He never took a title in his life, he borrowed money from his clansmen, and he rarely repaid his debts. He never became a warrior because he feared the sight of blood. Moreover, he died of an abominable illness. On the positive side, Unoka appears to have been a talented musician and gentle, if idle. He may well have been a dreamer, ill-suited to the chauvinistic culture into which he was born. The novel opens ten years after his death.

Obierika Okonkwo’s close friend, whose daughter’s wedding provides cause for festivity early in the novel. Obierika looks out for his friend, selling Okonkwo’s yams to ensure that Okonkwo won’t suffer financial ruin while in exile and comforting Okonkwo when he is depressed. Like Nwoye, Obierika questions some of the Igbo traditional strictures.

Ekwefi Okonkwo’s second wife, once the village beauty. Ekwefi ran away from her first husband to live with Okonkwo. Ezinma is her only surviving child, her other nine having died in infancy, and Ekwefi constantly fears that she will lose Ezinma as well. Ekwefi is good friends with Chielo, the priestess of the goddess Agbala. Okonkwo beats Ekwefi during the week of peace.

Enoch A fanatical convert to the Christian church in Umuofia. Enoch’s disrespectful act of ripping the mask off an egwugwu during an annual ceremony to honor the earth deity leads to the climactic clash between the indigenous and colonial justice systems. While Mr. Brown, early on, keeps Enoch in check in the interest of community harmony, Reverend Smith approves of his zealotry.

Ogbuefi Ezeudu The oldest man in the village and one of the most important clan elders and leaders. Ogbuefi Ezeudu was a great warrior in his youth and now delivers messages from the Oracle.

Chielo A priestess in Umuofia who is dedicated to the Oracle of the goddess Agbala. Chielo is a widow with two children. She is good friends with Ekwefi and is fond of Ezinma, whom she calls “my daughter.” At one point, she carries Ezinma on her back for miles in order to help purify her and appease the gods.

Akunna A clan leader of Umuofia. Akunna and Mr. Brown discuss their religious beliefs peacefully, and Akunna’s influence on the missionary advances Mr. Brown’s strategy for converting the largest number of clansmen by working with, rather than against, their belief system. In so doing, however, Akunna formulates an articulate and rational defense of his religious system and draws some striking parallels between his style of worship and that of the Christian missionaries.

Nwakibie A wealthy clansmen who takes a chance on Okonkwo by lending him 800 seed yams—twice the number for which Okonkwo asks. Nwakibie thereby helps Okonkwo build up the beginnings of his personal wealth, status, and independence.

Mr. Kiaga The native-turned-Christian missionary who arrives in Mbanta and converts Nwoye and many others.

Okagbue Uyanwa A famous medicine man whom Okonkwo summons for help in dealing with Ezinma’s health problems.

Maduka Obierika’s son. Maduka wins a wrestling contest in his mid-teens. Okonkwo wishes he had promising, manly sons like Maduka.

Obiageli The daughter of Okonkwo’s first wife. Although Obiageli is close to Ezinma in age, Ezinma has a great deal of influence over her.

Ojiugo Okonkwo’s third and youngest wife, and the mother of Nkechi.

Themes and motifs

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2009) |

Themes throughout the novel include change, loneliness, abandonment, and fear.

The following are respected theme statements connected to Things Fall Apart.

- Individuals derive strength from their society, and societies derive strength from the individuals who belong to them. In Things Fall Apart, Okonkwo builds his fortune and strength with the help of his society's customs. Likewise, Okonkwo's society benefits from his hard work and determination.

- In contacts between other cultures, beliefs about superiority or inferiority are invariably wrong-headed and destructive. When new cultures and religions meet, there is likely to be a struggle for dominance.

- Each culture’s world view is limited and partial, and each can benefit from understanding the world views of other cultures. For example, the Christians and Okonkwo's people have a limited view of each other, and have a very difficult time understanding and accepting one another's customs and beliefs.

- In spite of innumerable opportunities for understanding, people must strive to communicate. For example, Okonkwo and his son, Nwoye, speak the same language, but have a difficult time understanding one another because they are so different.

- A social value—such as individual ambition—which is constructive when balanced by other values, can become destructive when overemphasized at the expense of other values. For example, Okonkwo values tradition so highly that he cannot accept change. (It may be more accurate to say he values tradition because of the high cost he has paid to uphold it, i.e. killing Ikemefuna and moving to Mbanta). The Christian teachings render these large sacrifices on his part meaningless. The distress over the loss of tradition, whether driven by his love of the tradition or the meaning of his sacrifices to it, can be seen as the main reasons for his suicide.

- There is no such thing as a static culture; change is continual, and flexibility is necessary for successful adaptation. Because Okonkwo cannot accept the change the Christians bring, he cannot adapt.[3]

- The struggle between change and tradition is constant.[3]

- A rigid individual, unable to change with the times or to criticize his or her own beliefs, is liable to be tragically swept aside by history.[3]

- Definitions of masculinity vary throughout different societies. In this case, Okonkwo views aggression and action as masculinity.

Literary significance and reception

Things Fall Apart is a milestone in African literature. It has achieved the status of the archetypal modern African novel in English,[4] and is read in Nigeria and throughout Africa. It is studied widely in Europe and North America, where it has spawned numerous tertiary analytical works. It has achieved similar repute in India and Australia.[4] Considered Achebe's magnum opus, it has sold more than 8 million copies worldwide.[5] Time Magazine included the novel in its TIME 100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005.[6]

Achebe’s writing about African society is intended to extinguish the misconception that African culture had been savage and primitive by telling the story of the colonization of the Igbo from an African point of view. In Things Fall Apart, western culture is portrayed as being “arrogant and ethnocentric," insisting that the African culture needed a leader. As it had no kings or chiefs, Umofian culture was vulnerable to invasion by western civilization. It is felt that the repression of the Igbo language at the end of the novel contributes greatly to the destruction of the culture. Although Achebe favors the African culture of the pre-western society, the author attributes its destruction to the “weaknesses within the native structure.” Achebe portrays the culture as having “a religion, a government, a system of money, and an artistic tradition, as well as a judicial system.[7]

Achebe named Things Fall Apart from a line in William Butler Yeats's "The Second Coming," thus tying in the meaning of the poem itself. The missionaries' arrival begins the downfall of traditional Igbo society. This downfall destroys the Igbo way of life, leading to the death of Okonkwo, who was once a hero of the village.

Things Fall Apart has been called a modern Greek tragedy. It has the same plot elements as a Greek tragedy, including the use of a tragic hero, the following of the string model, etc. Okonkwo is a classic tragic hero, even if the story is set in more modern times. He shows multiple hamartia, including hubris (pride) and ate (rashness), and these character traits do lead to his peripeteia, or reversal of fortune, and his downfall at the end of the novel. He is distressed by social changes brought by white men, because he has worked so hard to move up in the traditional society. This position is at risk due to the arrival of a new values system. Those who commit suicide lose their place in the ancestor-worshipping traditional society, to the extent that they may not even be touched to give a proper burial. The irony is that Okonkwo completely loses his standing in both value systems. Okonkwo truly has good intentions, but his need to feel in control and his fear that other men will sense weakness in him drive him to make decisions, whether consciously or subconsciously, that he regrets as he progresses through his life.[8]

Language

In order to gain a wider audience—and also to respond directly to those British colonial writers who depicted Africans as ignorant and uncivilized—Achebe chose to write in English.

Gender roles

Gender differentiation is seen in Igbo classification of crimes. The narrator of Things Fall Apart states that "The crime [of killing Ezeudu's son] was of two kinds, male and female. Okonkwo had committed the female because it was an accident. He would be allowed to return to the clan after seven years."[9] Okonkwo fled to the land of his mother, Mbanta, because a man finds refuge with his mother. Uchendu explains this to Okonkwo:

"It is true that a child belongs to his father. But when the father beats his child, it seeks sympathy in its mother's hut. A man belongs to his fatherland when things are good and life is sweet. But when there is sorrow and bitterness, he finds refuge in his motherland. Your mother is there to protect you. She is buried there. And that is why we say that mother is supreme."[10]

References to history

The events of the novel unfold around the 1890s.[4] The majority of the story takes place in the village of Umuofia, located west of the actual Onitsha, on the east bank of the Niger River in Nigeria.[4] The culture depicted is similar to that of Achebe's birthplace of Ogidi, where Igbo-speaking people lived together in groups of independent villages ruled by titled elders. The customs described in the novel mirror those of the actual Onitsha people, who lived near Ogidi, and with whom Achebe was familiar.

Within forty years of the British arrival, by the time Achebe was born in 1930, the missionaries were well-established. Achebe's father was among the first to be converted in Ogidi, around the turn of the century. Achebe himself was an orphan, so it can safely be said the character of Nwoye, who joins the church because of a conflict with his father, is not meant to represent the author.[4] Achebe was raised by his grandfather. His grandfather, far from opposing Achebe's conversion to Christianity, allowed Achebe's Christian marriage to be celebrated in his compound.[4]

Political structures in the novel

Prior to British colonization, the Igbo people as featured in Things Fall Apart, lived in a patriarchal collective political system. Decisions were not made by a chief or by any individual but were rather decided by a council of male elders. Religious leaders were also called upon to settle debates reflecting the cultural focus of the Igbo people. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to explore and colonize Nigeria. Though the Portuguese are not mentioned by Achebe, the remaining influence of the Portuguese can be seen in many Nigerian surnames. The British entered Nigeria first through trade and then established The Royal Niger Colony in 1886. The success of the colony led to Nigeria becoming a British protectorate in 1901. The arrival of the British slowly began to deteriorate the traditional society. The British government would intervene in tribal disputes rather than allowing the Igbo to settle issues in a traditional manner. The frustration caused by these shifts in power is illustrated by the struggle of the protagonist Okonkwo in the second half of the novel Things Fall Apart.

Film, television, and theatrical adaptations

A dramatic radio program called Okonkwo was made of the novel in April 1961 by the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation. It featured Wole Soyinka in a supporting role.[11]

In 1987, the book was made into a very successful mini series directed by David Orere and broadcast on Nigerian television by the NTA (Nigerian Television Authority). It starred movie veterans like Pete Edochie, Nkem Owoh and Sam Loco.

References in popular culture

- The Philadelphia Hip Hop group the Roots named their fourth album Things Fall Apart.

- Vast Aire of Hip Hop group, Cannibal Ox, makes a reference to the book's title in the song, "The F-Word".

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Washington State University study guide

- ^ Newsweek's Top 100 Books: The Meta-List, LibraryThing

- ^ a b c "Things Fall Apart, Chinua Achebe: Introduction." Contemporary Literary Criticism. Ed. Jeffrey W. Hunter. Vol. 152. Gale Cengage, 2002. eNotes.com. 2006. 12 Jan, 2009 <[1]>

- ^ a b c d e f Kwame Anthony Appiah (1992), "Introduction" to the Everyman's Library edition.

- ^ Random House Teacher's Guide

- ^ ALL TIME 100 Novels, Time magazine

- ^ www.cliffnotes.com. Set in 1880s, in the Nigerian village of Umuofia, before missionaries and other outsiders had arrived, Things Fall Apart tells the story of the struggles, trials, and the eventual destruction of its main character, Okonkwo. His rise to prominence and his eventual fall acts as a metaphor reflecting the plight of the Umuofia native people. Play the story forward until the mid 1950’s, when it was written, and expand it to represent an African culture entirely subordinate to Western influence, and the scope and reach of the book is revealed.

- ^ Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. EMC Corporation. 2004. Noodle

- ^ Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. New York: First Anchor Books, 1994.

- ^ Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. EMC Corporation. 2003.

- ^ Ezenwa-Ohaeto (1997). Chinua Achebe: A Biography Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33342-3. P. 81.

External links

- Chinua Achebe discusses Things Fall Apart on the BBC World Book Club

- Teacher's Guide at Random House

- Study Resource for writing about Things Fall Apart

- Study guide

- Resource connecting the novel to historical evidence. From MSN Encarta [dead link]

- Words present in the novel used in past SATs Includes definitions, words in order from the book, and three different tests.

- Things Fall Apart Reviews

- Things Fall Apart on Wiki Summaries

- Things Fall Apart study guide, themes, analysis, teacher resources