Simplex algorithm

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2010) |

- See Nelder–Mead method for the downhill simplex or amoeba method of optimization theory

In mathematical optimization theory, the simplex algorithm or simplex method, created by the American mathematician George Dantzig in 1947, is a popular algorithm for numerically solving linear programming problems. The journal Computing in Science and Engineering listed it as one of the top 10 algorithms of the twentieth century.[1]

The name of the algorithm is derived from the concept of a simplex and was suggested by T. S. Motzkin.[2] Simplices are not actually used in the method, but one interpretation of it is that it operates on simplicial cones and these become simplices with an additional constraint.[3]

Efficiency

The simplex method is remarkably efficient in practice and was a great improvement over earlier methods such as Fourier–Motzkin elimination. It has been known since the 1970s that it has polynomial-time average-case complexity under various distributions. These results on "random" matrices still didn't quite capture the desired intuition that the method works well on "typical" matrices. In 2001 Spielman and Teng introduced the notion of smoothed complexity to provide a more realistic analysis of the performance of algorithms.[4]

However, in 1972, Klee and Minty[5] gave an example showing that the worst-case complexity of simplex method as formulated by Dantzig is exponential time. Since then, for almost every variation on the method, it has been shown that there is a family of linear programs for which it performs badly. It is an open question if there is a variation with polynomial time, or even sub-exponential worst-case complexity.

Other algorithms for solving linear programming problems are described in the linear programming article.

Overview

The simplex algorithm operates on linear programs in standard form, that is linear programming problems of the form,

- Minimize

- Subject to

with the variables of the problem, are the coefficients of the objective function, A a p×n matrix and constants. There is a straightforward process to convert any linear program into one in standard form so this results in no loss of generality.

In geometric terms, the feasible region

is a (possibly unbounded) convex polytope. There is a simple characterization of the extreme points or vertices of this polytope, namely is an extreme point if and only if the column vectors , where , are linearly independent[6]. In this context such a point is known as a basic feasible solution (BFS).

It can be shown that for a linear program in standard form, if the objective function has a minimum value on the feasible region then it has this value on (at least) one of the extreme points.[7] This in itself reduces the problem to a finite computation since there are finite number of extreme points, however the number of extreme points is unmanageably large for all but the smallest linear programs.[8]

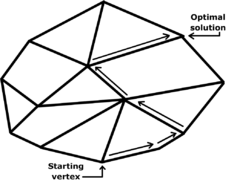

It can also be shown that if an extreme point is not a minimum point of the objective function then there is an edge containing the point so that the objective function is strictly decreasing on the edge moving away from the point.[9] If the edge is finite then the edge connects to another extreme point where the objective function has a smaller value, otherwise the objective function is unbounded below on the edge and the linear program has no solution. The simplex algorithm applies this insight by walking along edges of the polytope to extreme points with lower and lower objective values. This continues until the minimum value is reached or an unbounded edge is visited, concluding that the problem has no solution. The algorithm always terminates because the number of vertices in the polytope is finite; moreover since we jump between vertices always in the same direction (that of the objective function), we hope that the number of vertices visited will be small.[10]

The solution of a linear program is accomplished in two steps. In the first step, known as Phase I, a starting extreme point is found. Depending on the nature of the program this may be trivial, but in general it can be solved by applying the simplex algorithm to a modified version of the original program. The possible results of Phase I are either a basic feasible solution is found or that the feasible region is empty. In the latter case the linear program is called infeasible. In the second step, Phase II, the simplex algorithm is applied using the basic feasible solution found in Phase I as a starting point. The possible results from Phase II are either an optimum basic feasible solution or an infinite edge on which the objective function is unbounded below.

Standard form

The transformation of a linear program to one in standard form may be accomplished as follows.[11] First, for each variable with a lower bound other than 0, a new variable is introduced representing the difference between the variable and bound. The original variable can then be eliminated by substitution. For example, given the constraint

a new variable, y1, is introduced with

The second equation may be used to eliminate x1 from the linear program. In this way, all lower bound constraints may be changed to nonnegativity restrictions.

Second, for each remaining inequality constraint, a new variable, called a slack variable, is introduced to change the constraint to an equality constraint. This variable represents the difference between the two sides of the inequality and is assumed to be nonnegative. For example the inequalities

are replaced with

It is much easier to perform algebraic manipulation on inequalities in this form. In inequalities where ≥ appears such as the second one, some authors refer to the variable introduced as a surplus variable.

Third, each unrestricted variable is eliminated from the linear program. This can be done in two ways, one is by solving for the variable in one of the equations in which it appears and then eliminating the variable by substitution. The other is to replace the variable with the difference of two restricted variables. For example if z1 is unrestricted then write

The equation may be used to eliminate z1 from the linear program.

When this process is complete the feasible region will be in the form

It is also useful to assume that the rank of A is the number of rows. This results in no loss of generality since otherwise either the system Ax=b has redundant equations which can be dropped, or the system is inconsistent and the linear program has no solution.[12]

Canonical tableaux

A linear program in standard form can be represented as a tableau of the form

The first row defines the objective function and the remaining rows specify the constraints. (Note, different authors use different conventions as to the exact layout.) If the columns of A can be rearranged so that it contains the identity matrix of order p then the tableau is said to be in canonical form.[13] The variables corresponding to the columns of the identity matrix are called basic variables while the remaining variables are called nonbasic or free variables. If the nonbasic variables are assumed to be 0, then the values of the basic variables are easily obtained as entries in b and this solution is a basic feasible solution.

Conversely, given a basic feasible solution, the columns corresponding the nonzero variables can be expanded to a nonsingular matrix. If the corresponding tableau is multiplied by the inverse of this matrix then the result is a tableau in canonical form.[14]

Let

be a tableau in canonical form. Additional row-addition transformations can be applied to remove the coefficients cTB from the objective function. This process is called pricing out and results in a canonical tableau

where zB is the value of the objective function at the corresponding basic feasible solution. The updated coefficients, also known as relative cost coefficients, are the rates of change of the objective function with respect to the nonbasic variables.

Pivot operations

The geometrical operation of moving from a basic feasible solution to an adjacent basic feasible solution is implemented as a pivot operation. First, a nonzero pivot element is selected in a nonbasic column. The row containing this element is multiplied by its reciprocal to change this element to 1, and then multiples of the row are added to the other rows to change the other entries in the column to 0. The result is that, if the pivot element is in row r, then the column becomes the r-th column of the identity matrix. The variable for this column is now a basic variable, replacing the variable which corresponded to the r-th column of the identity matrix before the operation. In effect, the variable corresponding to the pivot column enters the set of basic variables and is called the entering variable, and the variable being replaced leaves the set of basic variables and is called the leaving variable. The tableau is still in canonical form but with the set of basic variables changed by one element.

Algorithm

Let a linear program be given by a canonical tableau. The simplex algorithm proceeds by performing successive pivot operations which each give an improved basic feasible solution; the choice of pivot element at each step is largely determined by the requirement that this pivot does improve the solution.

Entering variable selection

Since the entering variable will, in general, increase from 0 to a positive number, the value of the objective function will decrease if the derivative of the objective function with respect to this function is negative. Equivalently, the value of the objective function is decreased if the pivot column is selected so that the corresponding entry in the objective row of the tableau is positive.

If there is more than one column so that the entry in the objective row is positive then the choice of which one to add to the set of basic variables is somewhat arbitrary and several entering variable choice rules[15] have been developed.

If all the entries in the objective row are less than or equal to 0 then no choice of entering variable can be made and the solution is in fact optimal. It is easily seen to be optimal since the objective row now corresponds to an equation of the form

Note that by changing the entering variable choice rule so that it selects a column where the entry in the objective row is negative, the algorithm is changed so that it finds the maximum of the objective function rather than the minimum.

Leaving variable selection

Once the pivot column has been selected, the choice of pivot row is largely determined by the requirement that resulting solution will be feasible. First, only positive entries in the pivot column are considered since this guarantees that the value of the entering variable will be nonnegative. If there are no positive entries in the pivot column then the entering variable can take any nonnegative value with the solution remaining feasible. In this case the objective function is unbounded below and there is no minimum.

Next, the pivot row must be selected so that all the other basic variables remain positive. A calculation shows that this occurs when the resulting value of the entering variable is at a minimum. In other words, if the pivot column is c, then the pivot row r is chosen so that

is the minimum over all r so that acr > 0. This is called the minimum ratio test.[16] If there is more than one row for which the minimum is achieved then a dropping variable choice rule[17] can be used to make can be used to make the determination.

Example

Consider the linear program

- Minimize

- Subject to

With the addition of slack variables s and t, this is represented by the canonical tableau

where columns 5 and 6 represent the basic variables s and t and the corresponding basic feasible solution is

Columns 2, 3, and 4 can be selected as pivot columns, for this example column 4 is selected. The values of x resulting from the choice of rows 2 and 3 as pivot rows are 10/1=10 and 15/3=5 respectively. Of these the minimum is 5, so row 3 must be the pivot row. Performing the pivot produces

Now columns 4 and 5 represent the basic variables z and s and the corresponding basic feasible solution is

For the next step, there are no positive entries in the objective row and in fact

so the minimum value of Z is -20.

Finding an initial canonical tableau

In general, a linear program will not be given in canonical form and an equivalent canonical tableau must be found before the simplex algorithm can start. This can be accomplished by the introduction of artificial variables. Columns of the identity matrix are added as column vectors for these variables. The new tableau is in canonical form but it is not equivalent to the original problem. So a new objective function, equal to the sum of the artificial variables, is introduced and the simplex algorithm is applied to find the minimum; the modified linear program is called the Phase I problem.[18]

The simplex algorithm applied to the Phase I problem must terminate with a minimum value for the new objective function since, being the sum of nonnegative variables, its value is bounded below by 0. If the minimum is 0 then the artificial variables can be eliminated from the resulting canonical tableau producing a canonical tableau equivalent to the original problem. The simplex algorithm can then be applied to find the solution; this step is called Phase II. If the minimum is greater than 0 then there is no feasible solution for the Phase I problem where the artificial variables are all 0. This implies that the feasible region for the original problem is, in fact, empty and the original problem has no solution.

Example

Consider the linear program

- Minimize

- Subject to

This is represented by the (non-canonical) tableau

Introduce artificial variables u and v and objective function W=u+v, giving a new tableau

Note that the equation defining the original objective function is retained in anticipation of Phase II. After pricing out this becomes

Select column 5 as a pivot column, so the pivot row must be row 4, and the updated tableau is

Now select column 3 as a pivot column, for which row 3 must be the pivot row, to get

The artificial variables are now 0 and they may be dropped giving a canonical tableau equivalent to the original problem:

This is, fortuitously, already optimal and the optimum value for the original linear program is -130/7.

Degeneracy and cycling

If the values of all basic variables are strictly greater than 0, then a pivot must result in an improvement in the objective value. When this is always the case no set of basic variables occurs twice and the simplex algorithm must terminate after a finite number of steps. Basic feasible solutions where at least one of the basic variables is 0 are called degenerate and may result in pivots for which there is no improvement in the objective value. In this case there is no actual change in the solution but only a change in the set of basic variables. When several such pivots occur in succession there is the possibility the same set of basic variables will occur more than once and the simplex algorithm will cycle without producing a result. This occurs rarely in practice, though it depends on the nature of the linear program. Special entering variable and leaving variable selection rules have been devised which prevent cycling and thus guarantee that the simplex algorithm always terminates.[19]

Implementation

The tableau form used above to describe the algorithm lends itself to an immediate implementation in which the tableau is maintained as a rectangular (m+1)-by-(m+n+1) array. It is straightforward to avoid storing the m explicit columns of the identity matrix that will occur within the tableau by virtue of B being a subset of the columns of . This implementation is referred to as the standard simplex method. The storage and computation overhead are such that the standard simplex method is a prohibitively expensive approach to solving large linear programming problems.

In each simplex iteration, the only data required are the first row of the tableau, the (pivotal) column of the tableau corresponding to the entering variable and the right-hand-side. The latter can be updated using the pivotal column and the first row of the tableau can be updated using the (pivotal) row corresponding to the leaving variable. Both the pivotal column and pivotal row may be computed directly using the solutions of linear systems of equations involving the matrix B and a matrix-vector product using A. These observations motivate the revised simplex method, for which implementations are distinguished by their invertible representation of B.

In large linear programming problems A is typically a sparse matrix and, when the resulting sparsity of B is exploited when maintaining its invertible representation, the revised simplex method is a vastly more efficient solution procedure than the standard simplex method. Commercial simplex solvers are based on the primal (or dual) revised simplex method.

Fractional linear programming

Linear-fractional programming (LFP) is a generalization of linear programming (LP). Where the objective function of linear programs are linear functions, the objective function of a linear-fractional program is a ratio of two linear functions. In other words, a linear program is a fractional-linear program in which the denominator is the constant function having the value one everywhere. A fractional-linear program can be solved by a variant of the simplex algorithm.[20][21][22]

See also

References

- ^ Computing in Science and Engineering, volume 2, no. 1, 2000

- ^ Murty, Comment 2.2

- ^ Murty, Note 3.9

- ^ Spielman, Daniel; Teng, Shang-Hua (2001). "Smoothed analysis of algorithms: why the simplex algorithm usually takes polynomial time". Proceedings of the Thirty-Third Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing. ACM. pp. 296–305. doi:10.1145/380752.380813. ISBN 978-1-58113-349-3. arXiv:cs/0111050Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Greenberg, cites: V. Klee and G.J. Minty. "How Good is the Simplex Algorithm?" In O. Shisha, editor, Inequalities, III, pages 159–175. Academic Press, New York, NY, 1972

- ^ Murty, Theorem 3.1

- ^ Murty, Theorem 3.3

- ^ Murty, Section 3.13 p. 143

- ^ Murty, Section 3.8 p. 137

- ^ Murty, Section 3.8 p. 137

- ^ Follows Murty, Section 2.2

- ^ Murty, p. 173

- ^ Murty, section 2.3.2

- ^ Murty, section 3.12

- ^ Murty p. 66

- ^ Murty p. 66

- ^ Murty p. 67

- ^ Murty p.60

- ^ Murty p. 79

- ^ Chapter five: Craven, B. D. (1988). Fractional programming. Sigma Series in Applied Mathematics. Vol. 4. Berlin: Heldermann Verlag. p. 145. ISBN 3-88538-404-3. MR949209.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article

- Katta G. Murty, Linear Programming, Wiley, 1983. (comprehensive textbook and reference, through ellipsiodal algorithm of Khachiyan)

Further reading

- Dmitris Alevras and Manfred W. Padberg, Linear Optimization and Extensions: Problems and Extensions, Universitext, Springer-Verlag, 2001. (Problems from Padberg with solutions.)

- J. E. Beasley, editor. Advances in Linear and Integer Programing. Oxford Science, 1996. (Collection of surveys)

- R.G. Bland, New finite pivoting rules for the simplex method, Math. Oper. Res. 2 (1977) 103–107.

- Karl Heinz Borgwardt, The Simplex Algorithm: A Probabilistic Analysis, Algorithms and Combinatorics, Volume 1, Springer-Verlag, 1987. (Average behavior on random problems)

- Richard W. Cottle, ed. The Basic George B. Dantzig. Stanford Business Books, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 2003. (Selected papers by George B. Dantzig)

- George B. Dantzig and Mukund N. Thapa. 1997. Linear programming 1: Introduction. Springer-Verlag.

- George B. Dantzig and Mukund N. Thapa. 2003. Linear Programming 2: Theory and Extensions. Springer-Verlag.

- Template:Cite article

- Evar D. Nering and Albert W. Tucker, 1993, Linear Programs and Related Problems, Academic Press. (elementary)

- M. Padberg, Linear Optimization and Extensions, Second Edition, Springer-Verlag, 1999. (carefully written account of primal and dual simplex algorithms and projective algorithms, with an introduction to integer linear programming --- featuring the traveling salesman problem for Odysseus.)

- Christos H. Papadimitriou and Kenneth Steiglitz, Combinatorial Optimization: Algorithms and Complexity, Corrected republication with a new preface, Dover. (computer science)

- Alexander Schrijver, Theory of Linear and Integer Programming. John Wiley & sons, 1998, ISBN 0-471-98232-6 (mathematical)

- Terlaky, Tamás; Zhang, Shu Zhong (1993). "Pivot rules for linear programming: A Survey on recent theoretical developments". Annals of Operations Research. 46–47 (Degeneracy in optimization problems). Springer Netherlands: 203–233. doi:10.1007/BF02096264. ISSN 0254-5330. MR1260019.PDF file of (1991) preprint.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|1=and|2=(help); More than one of|number=and|issue=specified (help) - Michael J. Todd (2002). "The many facets of linear programming". Mathematical Programming. 91 (3).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) (Invited survey, from the International Symposium on Mathematical Programming.) - Frederick S. Hillier and Gerald J. Lieberman: Introduction to Operations Research, 8th edition. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-123828-X

- Thomas H. Cormen, Charles E. Leiserson, Ronald L. Rivest, and Clifford Stein. Introduction to Algorithms, Second Edition. MIT Press and McGraw-Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-262-03293-7. Section 29.3: The simplex algorithm, pp.790–804.

- Press, William H., et. al.: Numerical Recipes in C, Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43108-5. Section 10.8: Linear Programming and the Simplex Method, pp.430-444. (A different tableau format, for which the use of the word pivot is quite intuitive. Computer code in C.)

External links

- An Introduction to Linear Programming and the Simplex Algorithm by Spyros Reveliotis of the Georgia Institute of Technology.

- Greenberg, Harvey J., Klee-Minty Polytope Shows Exponential Time Complexity of Simplex Method University of Colorado at Denver (1997) PDF download

- LP-Explorer A Java-based tool which, for problems in two variables, relates the algebraic and geometric views of the tableau simplex method. Also illustrates the sensitivity of the solution to changes in the right-hand-side.

- Java-based interactive simplex tool hosted by Argonne National Laboratory.

- Simplex Method A good tutorial for Simplex Method with examples (also two-phase and M-method).

- Complex An Open Source Application for Linear Programming that resolves a giving model and shows step to step the iterations of the simplex method. (Penalization Method and Two Phases Method).

![{\displaystyle [\mathbf {A} \,\mathbf {I} ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ead85dd05097c22f607976f3e4edd5a8ac0b9ff1)