Put option

A "put" or "put option" is an option to sell an item at a preset price at some time in the future. It is a contract between two parties where one party (the buyer of the put) has the option, but not the obligation, to sell an item, typically a commodity or financial instrument such as a stock, to the other party (the seller of the put) at future date and at a predetermined price (the strike price) lower than the current market price. If the price of the specified item does not drop below the strike price within the time period specified by the contract neither party has any further obligation and the transaction is complete. If the price does drop below the strike price, the seller of the put has an obligation to buy the item from the other party at the strike price, so the seller or writer of the put has a maximum exposure set by the strike price should the market price of the item being optioned drop to zero.

Although neither party has to own the item being optioned at the time the contract is written, the prototypical case is where the buyer of the put does already own the item and wants to reduce their risk should its market price drop. Whereas the seller of the put does not own the object but is willing to accept future risk in exchange for immediate compensation. The perceived risk effectively determines the price of the put.

In this transaction, the buyer of the put is paying money upfront in order to reduce potential loss should the market price of the item drop. Therefore the buyer believes the market price will rise, but also recognizes a possibility that the price will drop and wants to set a floor on their future potential losses. The seller of the put is being paid to take on that risk should the market price drop and therefore they also believe the price will rise but are able to tolerate more risk than the buyer.

Instrument models

The terms for exercising the option's right to sell it differ depending on option style. A European put option allows the holder to exercise the put option for a short period of time right before expiration, while an American put option allows exercise at any time before expiration.

The most widely-traded put options are on equities, but they are traded on many other instruments such as interest rates (see interest rate floor) or commodities.

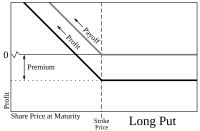

The put buyer either believes that the underlying asset's price will fall by the exercise date or hopes to protect a long position in it. The advantage of buying a put over short selling the asset is that the option owner's risk of loss is limited to the premium paid for it, whereas the asset short seller's risk of loss is unlimited (its price can rise greatly, in fact, in theory it can rise infinitely, and such a rise is the short seller's loss.) The put buyer's prospect (risk) of gain is limited to the option's strike price less the underlying's spot price and the premium/fee paid for it.

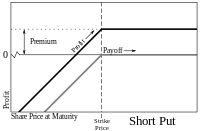

The put writer believes that the underlying security's price will rise, not fall. The writer sells the put to collect the premium. The put writer's total potential loss is limited to the put's strike price less the spot and premium already received. Puts can be used also to limit the writer's portfolio risk and may be part of an option spread.

A naked put, also called an uncovered put, is a put option whose writer (the seller) does not have a position in the underlying stock or other instrument. This strategy is best used by investors who want to accumulate a position in the underlying stock, but only if the price is low enough. If the buyer fails to exercise the options, then the writer keeps the option premium as a 'gift' for playing the game.

If the underlying stock's market price is below the option's strike price when expiration arrives, the option owner (buyer) can exercise the put option, forcing the writer to buy the underlying stock at the strike price. That allows the exerciser (buyer) to profit from the difference between the stock's market price and the option's strike price. But if the stock's market price is above the option's strike price at the end of expiration day, the option expires worthless, and the owner's loss is limited to the premium (fee) paid for it (the writer's profit).

The seller's potential loss on a naked put can be substantial. If the stock falls all the way to zero (bankruptcy), his loss is equal to the strike price (at which he must buy the stock to cover the option) minus the premium received. The potential upside is the premium received when selling the option: if the stock price is above the strike price at expiration, the option seller keeps the premium, and the option expires worthless. During the option's lifetime, if the stock moves lower, the option's premium may increase (depending on how far the stock falls and how much time passes). If it does, it becomes more costly to close the position (repurchase the put, sold earlier), resulting in a loss. If the stock price completely collapses before the put position is closed, the put writer potentially can face catastrophic loss.

Example of a put option on a stock

- Buying a put

A Buyer thinks the price of a stock will decrease. He pays a premium which he will never get back, unless it is sold before it expires. The buyer has the right to sell the stock at the strike price.

- Writing a put

The writer receives a premium from the buyer. If the buyer exercises his option, the writer will buy the stock at the strike price. If the buyer does not exercise his option, the writer's profit is the premium.

- 'Trader A' (Put Buyer) purchases a put contract to sell 100 shares of XYZ Corp. to 'Trader B' (Put Writer) for $50 per share. The current price is $55 per share, and 'Trader A' pays a premium of $5 per share. If the price of XYZ stock falls to $40 a share right before expiration, then 'Trader A' can exercise the put by buying 100 shares for $4,000 from the stock market, then selling them to 'Trader B' for $5,000.

- Trader A's total earnings (S) can be calculated at $500. The sale of the 100 shares of stock at a strike price of $50 to 'Trader B' = $5,000 (P). The purchase of 100 shares of stock at $40 = $4,000 (Q). The put option premium paid to trader B for buying the contract of 100 shares at $5 per share, excluding commissions = $500 (R). Thus S = P - (Q+R) = $5,000 - ($4,000+$500) = $500.

- If, however, the share price never drops below the strike price (in this case, $50), then 'Trader A' would not exercise the option (because selling a stock to 'Trader B' at $50 would cost 'Trader A' more than that to buy it). Trader A's option would be worthless and he would have lost the whole investment, the fee (premium) for the option contract, $500 (5 per share, 100 shares per contract). Trader A's total loss are limited to the cost of the put premium plus the sales commission to buy it.

A put option is said to have intrinsic value when the underlying instrument has a spot price (S) below the option's strike price (K). Upon exercise, a put option is valued at K-S if it is "in-the-money", otherwise its value is zero. Prior to exercise, an option has time value apart from its intrinsic value. The following factors reduce the time value of a put option: shortening of the time to expire, decrease in the volatility of the underlying, and increase of interest rates. Option pricing is a central problem of financial mathematics.

Value of a put

This examples lead to the following formal reasoning. Fix an underlying financial instrument. Let be a put option for this instrument, purchased at time , expiring at time , with exercise (strike) price ; and let be the price of the underlying instrument.

Assume the owner of the option , wants to make no loss, and does not want to actually possess the underlying instrument, . Then either (i) the person will purchase at expiry, and then immediately exercise the selling option; or (ii) the person will not exercise the option (which subsequently becomes worthless). In (i), the pay-off would be ; in (ii) the pay-off would be . So if (i) or (ii) occurs; if then (ii) occurs.

Hence the pay-off, i.e. the value of the put option at expiry, is

which is alternatively written or .

![{\displaystyle S:[0,T]\to \mathbb {R} }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/49384e9254296ea32d42522c759ec096811c03ce)