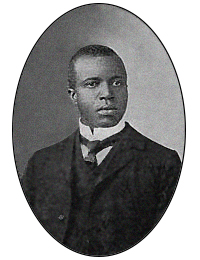

Scott Joplin

Scott Joplin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Scott Joplin |

| Genres | Ragtime, march, waltz, and song |

| Occupation(s) | Composer musician, and pianist |

| Instrument(s) | Piano, Violin, Banjo |

| Years active | 1895–1917 |

Scott Joplin (c. 1867 – April 1, 1917) was an American composer and pianist. He achieved fame for his unique ragtime compositions, and was dubbed the "King of Ragtime." During his brief career, Joplin wrote 44 original ragtime pieces, one ragtime ballet, and two operas. One of his first pieces, the "Maple Leaf Rag", became ragtime's first and most influential hit, and has been recognized as the archetypal rag.

He was born into a musical African-American family of laborers in eastern Texas, and developed his musical knowledge with the help of local teachers. During the late 1880s he travelled around the American South as an itinerant musician, and went to Chicago for the World's Fair of 1893 which played a major part in making ragtime a national craze by 1897.

Publication of his "Maple Leaf Rag" in 1899 brought him fame and had a profound influence on subsequent writers of ragtime. It also brought the composer a steady income for life with royalties of one cent per sale, equivalent to 37 cents per sale in current value. During his lifetime, Joplin did not reach this level of success again and frequently had financial problems, which contributed to the loss of his first opera, A Guest of Honor. He continued to write ragtime compositions, and moved to New York in 1907. He attempted to go beyond the limitations of the musical form which made him famous, without much monetary success. His second opera, Treemonisha, was not received well at its partially staged performance in 1915. He died from complications of tertiary syphilis in 1917.

Joplin's music was rediscovered and returned to popularity in the early 1970s with the release of a million-selling album of Joplin's rags recorded by Joshua Rifkin, followed by the Academy Award–winning movie The Sting which featured several of his compositions, such as "The Entertainer". The opera Treemonisha was finally produced in full to wide acclaim in 1972. In 1976, Joplin was posthumously awarded a Pulitzer Prize.

Texas (c. 1867–1880s)

Scott Joplin, the second of six[1] children, was born in eastern Texas, outside of Texarkana,[2] to Giles Joplin and Florence Givins. His birth, like many others, represented the first post-slavery generation of African-Americans. Although for many years his birth date was accepted as November 24, 1868, research has revealed that this is almost certainly inaccurate – the most likely approximate date being the second half of 1867.[3] In addition to Scott, other children of Giles and Florence were Monroe, Robert, Rose, William, and Johnny.[4] His father was an ex-slave from North Carolina and his mother was a freeborn African American woman from Kentucky.[5] After moving to Texarkana a few years following Joplin's birth, Giles began working as a common laborer for the railroad. Florence did laundry and cleaning for additional income. Joplin was given a rudimentary musical education by his musical family, Florence playing the banjo and singing, and Giles playing and teaching the violin to Joplin, Robert and William; at the age of seven he was allowed to play piano in both a neighbor's house and at the home of an attorney while his mother worked.[6]

At some point in the early 1880s, Giles Joplin left the family for another woman, leaving Florence to provide for her children through domestic work. Biographer Susan Curtis speculated that his mother's support of Joplin's musical education was an important causal factor in this separation; his father argued that it took the boy away from practical employment which would have supplemented the family income.[7]

According to a family friend, the young Joplin was serious and ambitious. While in elementary school, he spent his after-school hours studying music and learning to play piano. While a few local teachers aided him, he received most of his serious music education from Julius Weiss, a German-Jewish music professor who had immigrated to the U.S.[8] Weiss had studied music at a university in Germany and was listed in town records as a "Professor of music." Impressed by Joplin's talent, and realizing his family's dire straits, Weiss taught him free of charge. He tutored the 11-year-old Joplin until he was 16, during which time he introduced him to folk and classical music, including opera, sometimes playing the classics for him along with describing the great composers. Weiss supported the young composer's ambitions[9] and helped his mother acquire a used piano from another student. Joplin, according to his wife Lottie, never forgot Weiss, and in his later years, when he achieved fame as a composer, sent his former teacher "gifts of money when he was old and ill," until Weiss died.[8]

Joplin played music at church gatherings and for non-religious entertainments such as African-American dances. Although it is likely he played well-known dances of the era, "waltzes, polkas, and schottisches", it is possible he played his own compositions; biographer Curtis describes an eye-witness, Zenobia Campbell, recalling him playing his own compositions; "He did not have to play anybody else's music. He made up his own, and it was beautiful; he just got his music out of the air."[7][10]

Southern states and Chicago (1880s–1894)

In the late 1880s, having performed at various local events as a teenager, Joplin chose to give up his only steady employment as a laborer with the railroad and left Texarkana to work as traveling musician.[11] He was soon to discover that there were few opportunities for black pianists, however; besides the church, brothels were one of the few options for obtaining steady work. Joplin played pre-ragtime 'jig-piano' in various red-light districts throughout the mid-South.[12]

By the early 1890s, Ragtime had become popular among African-Americans in the cities of St. Louis and Chicago. In 1893 large numbers of African-American musicians, including Joplin, made their way to Chicago to perform for the visitors at the World's Fair. They found work in the cafés, saloons and brothels that lined the fair and the city's seedy and corrupt[13] "Tenderloin" district. While in Chicago, Joplin formed his first band and began arranging music for the group to perform. Although the World's Fair was "not congenial to African Americans," he still found that his music, as well as that of other black performers, was popular with visitors.[14] The exposition was attended by 27 million Americans and had a profound effect on many areas of American cultural life, including ragtime. Although specific information is sparse, numerous sources have credited the Chicago World Fair with spreading the popularity of ragtime.[15] By 1897 ragtime had become a national craze in American cities, and was described by the St. Louis Dispatch as "a veritable call of the wild, which mightily stirred the pulses of city bred people."[16]

Missouri (1894–1907)

In 1894 Joplin arrived in Sedalia, Missouri. At first, Joplin stayed with the family of Arthur Marshall, at the time a 13-year old boy but later one of Joplin's students and a rag-time composer in his own right.[21] There is no record of Joplin having a permanent residence in the town at until 1904 as Joplin was making a living as a touring musician.

In the 1890s, the town had a population of approximately 14,000 and was the center of commerce and transport for the region.[22] The town's saloons and brothels of the red-light district on Main St, nicknamed "Battle Row", provided employment for musicians, and it is likely that Joplin worked in this area. The town was attractive for other reasons; race-relations between Whites and Blacks in Sedalia were relatively good, especially when compared to other similar communities in Missouri in this period, there is no record of public lynchings in the area 1890s, there were several prominent black citizens who held minor positions in the Republican Party, and the George R. Smith College, one of the nation's first colleges for the education of blacks, opened in 1894. In addition, Sedalia was described by a black resident of the town at the time as the "musical town of the West", because music was a major leisure-time activity.[23][24]

There is little precise evidence known about Joplin's activities at this time, although he performed as a solo musician at dances and at the major black clubs in Sedalia, the "Black 400" club, and the "Maple Leaf Club". He performed in the Queen City Cornet Band, and his own six-piece dance orchestra. A tour with his own singing group, the Texas Medley Quartet, gave him his first opportunity to publish his own compositions and it is known that he went to Syracuse, New York and Texas. Two businessmen from New York published Joplin's first two works, the songs "Please Say You Will", and "A Picture of her Face" in 1895.[25] Joplin's visit to Temple, Texas enabled him to have three pieces published there in 1896, including the "Crush Collision March" which commemorated a planned train crash on the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad on 15 September which he may have witnessed. The March was described by one of Joplin's biographers as a "special... early essay in ragtime",[26] While in Sedalia he was teaching piano to students who included Arthur Marshall, composer and pianist Brun Campbell, and Scott Hayden, all of whom became ragtime composers in their own right.[27] In turn, Joplin enrolled at the George R. Smith College where he apparently studied "advanced harmony and composition". The College records were destroyed in a fire in 1925,[28] and biographer Edward A. Berlin notes that it was unlikely that a small college for African-Americans would be able to provide such a course.[29][30][31]

In 1899, Joplin married Belle, the sister-in-law of collaborator Scott Hayden. Although there were hundreds of rags in print by the time of the "Maple Leaf Rag's" publication, Joplin was not far behind. His first published rag was "Original Rags" (March 1899) had been completed in 1897, the same year as the first ragtime work in print, the "Mississippi Rag" by William Krell. The "Maple Leaf Rag" was likely to have been known in Sedalia before its publication in 1899; Brun Campbell claimed to have seen the manuscript of the work in around 1898.[32] The exact circumstances which lead to the Maple Leaf Rag's publication are unknown, and there are various different versions of the event which contradict each other. After several unsuccessful approaches to publishers, Joplin signed a contract with John Stillwell Stark, a retailer of musical instruments who later became his most important publisher, on 10 August 1899 for a 1% royalty on all sales of the rag, with a minimum sales price of 25c.[33] It is possible that the rag was named after the Maple Leaf Club, although there is no direct evidence to prove the link, and there were many other possible sources for the name in and around Sedalia at the time.[34]

There have been many claims about the sales of the "Maple Leaf Rag", for example that Joplin was the first musician to sell 1 million copies of a piece of instrumental music.[31] Joplin's first biographer, Rudi Blesh wrote that during its first six months the piece sold 75,000 copies, and became "the first great instrumental sheet music hit in America".[35] However, research by Joplin's later biographer Edward A. Berlin demonstrated that this was not the case; the initial print-run of 400 took one year to sell, and under the terms of Joplin's contract with a 1% royalty would have given Joplin an income of $4 (or approximately $146 at current prices). Later sales were steady and would have given Joplin an income which would have covered his expenses; in 1909 estimated sales would have given him an income of $600 annually (approximately $20,347 in current prices).[36]

The "Maple Leaf Rag" did serve as a model for the hundreds of rags to come from future composers, especially in the development of classic ragtime.[37] After the publication of the "Maple Leaf Rag", Joplin was soon being described as "King of rag time writers", not least by himself[38] on the covers of his own work, such as "The Easy Winners" and "Elite Syncopations".

After the Joplins' move to St. Louis in early 1900, they had a baby daughter who died only a few months after birth. Joplin's relationship with his wife was difficult as she had no interest in music; they eventually separated and then divorced.[39] About this time, Joplin collaborated with Scott Hayden in the composition of four rags.[40] It was in St. Louis that Joplin produced some of his best-known works, including "The Entertainer", "March Majestic", and the short theatrical work "The Ragtime Dance".

In June 1904, Joplin married Freddie Alexander of Little Rock, Arkansas, the young woman to whom he had dedicated "The Chrysanthemum" (1904). She died on September 10, 1904 of complications resulting from a cold, ten weeks after their wedding.[38] Joplin's first work copyrighted after Freddie's death, "Bethena" (1905), was described by one biographer as "an enchantingly beautiful piece that is among the greatest of ragtime waltzes".[41]

During this time, Joplin created an opera company of 30 people and produced his first opera A Guest of Honor for a national tour. It is not certain how many productions were staged, or even if this was an all-black show or a racially mixed production (which would have been unusual for 1903). During the tour, either in Springfield, Illinois, or Pittsburg, Kansas, someone associated with the company stole the box office receipts. Joplin could not meet the company's payroll or pay for it's lodgings at a theatrical boarding house. It is believed the score for A Guest of Honor was lost and perhaps destroyed because of non-payment of the company's boarding house bill.[42]

New York (1907–1917)

In 1907, Scott Joplin moved to New York City, which he believed was the best place to find a producer for a new opera. After his move to New York, Joplin met Lottie Stokes, whom he married in 1909.[40] In 1911, unable to find a publisher, Joplin undertook the financial burden of publishing Treemonisha himself in piano-vocal format. In 1915, as a last ditch effort to see it performed, he invited a small audience to hear it at a rehearsal hall in Harlem. Poorly-staged and with only Joplin on piano accompaniment, it was "a miserable failure," the public being not yet ready for "crude" black musical forms, so different from the style of European grand opera of that time.[43] The audience, including potential backers, was indifferent and walked out.[39] Scott writes that "after a disastrous single performance ... Joplin suffered a breakdown. He was bankrupt, discouraged, and worn out." He concludes that few American artists of his generation faced such obstacles: "Treemonisha went unnoticed and unreviewed, largely because Joplin had abandoned commercial music in favor of art music, a field closed to African Americans."[27] In fact, it was not until the 1970s that the opera received a full theatrical staging.

In 1914, Joplin and Lottie self-published his "Magnetic Rag" using the name the "Scott Joplin Music Company" which had been formed the previous December.[44] Biographer Vera Brodsky Lawrence speculates that Joplin was aware of his advancing deterioration due to syphilis and was "consciously racing against time." In her sleeve notes on the 1992 Deutsche Grammophon release of Treemonisha she notes that he "plunged feverishly into the task of orchestrating his opera, day and night, with his friend Sam Patterson standing by to copy out the parts, page by page, as each page of the full score was completed."[43]

By 1916, Joplin was suffering from tertiary syphilis and a resulting descent into madness.[45][46] In January 1917, he was admitted to Manhattan State Hospital, a mental institution.[38] He died there on April 1, 1917 of dementia.[43][47] After Joplin's death at the age of just 49, from advanced syphilis, he was buried in a pauper's grave that remained unmarked for 57 years. His grave at Saint Michaels Cemetery, in East Elmhurst, was finally honored in 1974.

Works

The combination of classical music, the musical atmosphere present around Texarkana (including work songs, gospel hymns, spirituals and dance music) and Joplin's natural ability has been cited as contributing significantly to the invention of a new style which blended both African-American musical styles with European forms and melodies, and which first became celebrated in the 1890s: ragtime.[7]

When Joplin was learning the piano, serious musical circles condemned ragtime because of its association with the vulgar and inane songs "cranked out by the tune-smiths of Tin Pan Alley."[48] As a composer Joplin refined ragtime, elevating it above the low and unrefined form played by the "wandering honky-tonk pianists... playing mere dance music" of popular imagination.[49] This new art form, the classic rag, combined Afro-American folk music's syncopation and nineteenth-century European romanticism, with its harmonic schemes and its march-like tempos.[40][50] In the words of one critic, "ragtime was basically... an Afro-American version of the polka, or its analog, the Sousa-style march."[51] With this as a foundation, Joplin intended his compositions to be played exactly as he wrote them – without improvisation.[27] Joplin wrote his rags as "classical" music in miniature form in order to raise ragtime above its "cheap bordello" origins and produced work which opera historian Elise Kirk described as "...more tuneful, contrapuntal, infectious, and harmonically colorful than any others of his era."[12]

It has been speculated that Joplin's achievements were influenced by his classically trained German music teacher Julius Weiss, who may have brought a polka rhythmic sensibility from the old country to the 11-year old.[52] As Curtis put it "The educated German could open up the door to a world of learning and music of which young Joplin was largely unaware."[48]

Joplin's first, and most significant hit the "Maple Leaf Rag" was described as the "archetype" of the classic rag, influencing subsequent rag composers for at least 12 years after its initial publication thanks to its rhythmic patterns, melody lines, and harmony,[37] although with the exception of Joseph Lamb they generally failed to enlarge upon it.[53]

Treemonisha

The opera's setting is a former slave community in an isolated forest near Joplin's childhood town Texarkana in September 1884. The plot centers on an 18 year old woman Treemonisha who is taught to read by a white woman, and then leads her community against the influence of conjurers who prey on ignorance and superstition. Treemonisha is abducted and is about to be thrown into a wasps' nest when her friend Remus rescues her. The community realizes the value of education and the liability of their ignorance before choosing her as their teacher and leader.[54][55][56]

Joplin wrote both the score and the libretto for the opera, which largely follows the form of European opera with many conventional arias, ensembles and choruses. In addition the themes of superstition and mysticism which are evident in Treemonisha are common in the operatic tradition, and certain aspects of the plot echo devices in the work of the German composer Richard Wagner (of which Joplin was aware); a sacred tree under which Treemonisha is found recalls the tree from which Siegmund takes his enchanted sword in Die Walküre, and the retelling of the heroine's origins echos aspects of the opera Siegfried. In addition, African-American folk tales also influence the story, with the wasp nest incident being similar to the story of Br'er Rabbit and the briar patch.[57]

Treemonisha is not a ragtime opera because Joplin employed the styles of ragtime and other black music sparingly, using them to convey "racial character", and to celebrate the music of his childhood at the end of the 19th century. The opera has been seen as a valuable record of rural black music from 1870s–1890s re-created by a "skilled and sensitive participant".[58]

Berlin speculates about parallels between the plot and Joplin's own life. He notes that Lottie Joplin (the composer's third wife) saw a connection between the character Treemonisha's wish to lead her people out of ignorance, and a similar desire in the composer. In addition, it has been speculated that Treemonisha represents Freddie, Joplin's second wife, because the date of the opera's setting was likely to have been the month of her birth.[59]

At the time of the opera's publication in 1911, the American Musician and Art Journal praised it as "an entirely new form of operatic art".[60] Later critics have also praised the opera as occupying a special place in American history, with its heroine "a startlingly early voice for modern civil rights causes, notably the importance of education and knowledge to African American advancement."[61] Curtis's conclusion is similar: "In the end, Treemonisha offered a celebration of literacy, learning, hard work, and community solidarity as the best formula for advancing the race."[56] Berlin describes it as a "fine opera, certainly more interesting than most operas then being written in the United States", but later states that Joplin's own libretto showed the composer "was not a competent dramatist" with the book not up to the same quality as the music.[62]

Performance skills

Joplin's skills as a pianist were described in glowing terms by a Sedalia newspaper in 1898, and fellow ragtime composers Arthur Marshall and Joe Jordan both said that he played the instrument well.[40] However, the son of publisher John Stark stated that Joplin was a rather mediocre pianist and that he composed on paper, rather than at the piano. Artie Matthews recalled the "delight" the St. Louis players took in outplaying Joplin.[64]

While Joplin never made an audio recording, his playing is preserved on seven piano rolls for use in mechanical player pianos. All seven were made in 1916. Of these, the six released under the Connorized label show evidence of significant editing,[65] probably by William Axtmann, the staff arranger at Connorized.[66] Berlin theorizes that by the time Joplin reached St. Louis he may have been experiencing discoordination of the fingers, tremors and an inability to speak clearly, symptoms of syphilis, the disease that took his life in 1917.[67] The second roll recording of "Maple Leaf Rag" on the UniRecord label from June 1916 was described by biographer Blesh as "... shocking... disorganized and completely distressing to hear."[68] While there is disagreement among piano-roll experts about the accuracy of the reproduction of a player's performance,[69][70][71][72] Berlin notes that the "Maple Leaf Rag" roll was "painfully bad" and likely to be the truest record of Joplin's playing at the time. The roll, however, does not reflect his abilities earlier in life.[65]

Legacy

Joplin and his fellow ragtime composers rejuvenated American popular music, fostering an appreciation for African American music among European Americans by creating exhilarating and liberating dance tunes, changing American musical taste. "Its syncopation and rhythmic drive gave it a vitality and freshness attractive to young urban audiences indifferent to Victorian proprieties... Joplin's ragtime expressed the intensity and energy of a modern urban America."[27]

Joshua Rifkin, a leading Joplin recording artist, wrote that "a pervasive sense of lyricism infuses his work, and even at his most high-spirited, he cannot repress a hint of melancholy or adversity... He had little in common with the fast and flashy school of ragtime that grew up after him."[73] Joplin historian Bill Ryerson adds that "In the hands of authentic practitioners like Joplin, ragtime was a disciplined form capable of astonishing variety and subtlety... Joplin did for the rag what Chopin did for the mazurka. His style ranged from tones of torment to stunning serenades that incorporated the bolero and the tango."[39]

Joplin biographer Susan Curtis expands on those observations:

- "When Scott Joplin syncopated his way into the hearts of millions of Americans at the turn of the century, he helped revolutionize American music and culture. His ragged rhythms and lilting melodies made people want to tap their feet, slap their thighs, or dance with happy abandon. As Americans embraced his music, they participated in a dramatic transformation of American popular culture – their Victorian restraint gave way to modern exuberance. And whether in the elegant parlors of comfortable, respectable American homes or in the honky tonks and cafes of America's sporting districts, ragtime music accompanied a reorientation of cultural values in America in the twentieth century. The excellence and appeal of his compositions earned for Joplin the generally accepted title "King of Ragtime".[74]

Composer and actor Max Morath found it striking that the vast majority of Joplin's work did not enjoy the popularity of the "Maple Leaf Rag", because while the compositions were "of increasing lyrical beauty and delicate syncopation" they remained "obscure" and "unheralded" during his lifetime.[53] Joplin apparently realized that his music was ahead of its time: As music historian Ian Whitcomb mentions that Joplin "opined that 'Maple Leaf Rag' would make him 'King of Ragtime Composers' but he also knew that he would not be a pop hero in his own lifetime. 'When I'm dead twenty-five years, people are going to recognize me,' he told a friend." Just over thirty years later he was recognized, and later historian Rudi Blesh would write a large book about ragtime, which he dedicated to the memory of Scott Joplin.[49]

Although he was penniless and disappointed at the end of his life, Joplin set the standard for ragtime compositions and played a key role in the development of ragtime music. And as a pioneer composer and performer, he helped pave the way for young black artists to reach American audiences of both races. After his death, jazz historian Floyd Levin noted: "those few who realized his greatness bowed their heads in sorrow. This was the passing of the king of all ragtime writers, the man who gave America a genuine native music."[75]

Revival

After his death in 1917, Joplin's music and ragtime in general waned in popularity as new forms of musical styles, such as jazz and novelty piano, emerged. Even so, jazz bands and recording artists such as Tommy Dorsey in 1936, Jelly Roll Morton in 1939 and J. Russell Robinson in 1947 released recordings of Joplin compositions. "Maple Leaf Rag" was the Joplin piece found most often on 78 rpm records.[76]

In the 1960s, a small-scale reawakening of interest in classic ragtime was underway among some American music scholars such as Trebor Tichenor, William Bolcom, William Albright and Rudi Blesh. In 1968, Bolcom and Albright interested Joshua Rifkin, a young musicologist, in the body of Joplin's work. Together, they hosted an occasional ragtime-and-early-jazz evening on WBAI radio.[77]

In November 1970, Rifkin released a recording called Scott Joplin: Piano Rags[78] on the classical label Nonesuch. It sold 100,000 copies in its first year and eventually became Nonesuch's first million-selling record.[79] The Billboard "Best-Selling Classical LPs" chart for 28 September 1974 has the record at number 5, with the follow-up "Volume 2" at number 4, and a combined set of both volumes at number 3. Separately both volumes had been on the chart for 64 weeks. In the top 7 spots on that chart, 6 of the entries were recordings of Joplin's work, three of which were Rifkin's.[80] Record stores found themselves for the first time putting ragtime in the classical music section. The album was nominated in 1971 for two Grammy Award categories: Best Album Notes and Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (without orchestra). Rifkin was also under consideration for a third Grammy for a recording not related to Joplin, but at the ceremony on March 14, 1972, Rifkin did not win in any category.[81] He did a tour in 1974, which included appearances on BBC Television and a sell-out concert at London's Royal Festival Hall.[82] In 1979 Alan Rich in the New York Magazine wrote that by giving artists like Rifkin the opportunity to put Joplin's music on disk Nonesuch Records "created, almost alone, the Scott Joplin revival."[83]

In January 1971, Harold C. Schonberg, music critic at the New York Times, having just heard the Rifkin album, wrote a featured Sunday edition article entitled "Scholars, Get Busy on Scott Joplin!"[84] Schonberg's call to action has been described as the catalyst for classical music scholars, the sort of people Joplin had battled all his life, to conclude that Joplin was a genius.[85] Vera Brodsky Lawrence of the New York Public Library published a two-volume set of Joplin works in June 1971, entitled The Collected Works of Scott Joplin, stimulating a wider interest in the performance of Joplin's music that included a recording called Joplin: The Red Back Book by Gunther Schuller, a french horn player and music professor.

Marvin Hamlisch lightly adapted Joplin's music for the 1973 film The Sting, for which he won an Academy Award for Best Original Song Score and Adaptation on April 2, 1974.[86] His version of "The Entertainer" reached number 3 on the Billboard Hot 100 and the American Top 40 music chart on May 18, 1974,[87][88] prompting The New York Times to write, "the whole nation has begun to take notice".[82] Thanks to the film and its score, Joplin's work became appreciated in both the popular and classical music world, becoming (in the words of music magazine Record World), the "classical phenomenon of the decade".[89]

On October 22, 1971, excerpts from Treemonisha were presented in concert form at Lincoln Center with musical performances by Bolcom, Rifkin and Mary Lou Williams supporting a group of singers.[90] Finally, on January 28, 1972, T.J. Anderson's orchestration of Treemonisha was staged for two consecutive nights, sponsored by the Afro-American Music Workshop of Morehouse College in Atlanta, with singers accompanied by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra[91] under the direction of Robert Shaw, and choreography by Katherine Dunham. Schonberg remarked in February 1972 that the "Scott Joplin Renaissance" was in full swing and still growing.[92] In May 1975, Treemonisha was staged in a full opera production by the Houston Grand Opera. The company toured briefly, then settled into an eight-week run in New York on Broadway at the Palace Theater in October and November. This appearance was directed by Gunther Schuller, and soprano Carmen Balthrop alternated with Kathleen Battle as the title character.[91] An "original Broadway cast" recording was produced. Because of the lack of national exposure given to the brief Morehouse College staging of the opera in 1972, many Joplin scholars wrote that the Houston Grand Opera's 1975 show was the first full production.[90]

1974 saw the Royal Ballet, under director Kenneth MacMillan, create Elite Syncopations a ballet based on tunes by Joplin and other composers of the era.[93] That year also brought the premiere by the Los Angeles Ballet of Red Back Book, choreographed by John Clifford to Joplin rags from the collection of the same name, including both solo piano performances and arrangements for full orchestra.

Other awards and recognition

1970: Joplin was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame by the National Academy of Popular Music.[94]

1976: Joplin was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize for his special contribution to American music.[95]

1977: Motown Productions produced Scott Joplin, a biographical film starring Billy Dee Williams as Joplin, released by Universal Pictures.[96]

1983: the United States Postal Service issued a stamp of the composer as part of its Black Heritage commemorative series.[97]

1989: Joplin received a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[98]

2002: a collection of Scott Joplin's own performances recorded on piano rolls in the 1900s was included by the National Recording Preservation Board in the Library of Congress National Recording Registry.[99] The board annually selects songs that are "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

References

Notes

- ^ Jasen & Tichenor (1978) p. 82.

- ^ "Scott Joplin". Texas Music History Online. Retrieved 2006-11-22.

- ^ Berlin, Edward A. "Scott Joplin: Brief Biographical Sketch". Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ^ 1880 United States Federal Census, as quoted in Berlin (1994), p. 6.

- ^ Kirchner (2005) p. 32.

- ^ Berlin (1994) p. 6.

- ^ a b c Curtis (2004) p. 38.

- ^ a b Albrecht (1979) p.89 - 105.

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 7 – 8.

- ^ Curtis (2004) p. 126.

- ^ Christensen (1999) p. 442

- ^ a b Kirk (2001) p. 190.

- ^ "Definition". Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com LLC. 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ^ Christensen (1999) p. 442.

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 11 & 12.

- ^ St. Louis Dispatch, quoted in Scott & Rutkoff (2001) p. 36

- ^ Jasen (1981) p. 319 - 320.

- ^ Berlin (1994) p. 131 & 132.

- ^ Edwards 2010.

- ^ RedHotJazz.

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 24 – 25.

- ^ Berlin (1994) p. 14.

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 14 & 18.

- ^ Palmer 1976, p. 21.

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 25 – 27.

- ^ Blesh (1981) p. xviii.

- ^ a b c d Scott & Rutkoff (2001) p. 37

- ^ Berlin (1994) p. 19

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 31–34

- ^ Berlin (1994) p. 27.

- ^ a b Edwards 2008.

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 47 & 52.

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 56 & 58.

- ^ Berlin (1994) p. 62.

- ^ Blesh (1981)p. xxiii.

- ^ Berlin (1994) p. 56 & 58.

- ^ a b Blesh (1981) p. xxiii.

- ^ a b c Berlin 1998.

- ^ a b c Ryerson (1973)

- ^ a b c d Jasen & Tichenor (1978) p. 88

- ^ Berlin (1994) p. 149.

- ^ "Profile of Scott Joplin". Classical.net. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

- ^ a b c Kirk (2001) p. 191. Cite error: The named reference "Kirk191" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 226 & 230.

- ^ Berlin (1994) p. 239.

- ^ Walsh, Michael (1994-09-19). "American Schubert". Time. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

- ^ Scott & Rutkoff (2001) p. 38.

- ^ a b Curtis (2004) p. 37.

- ^ a b Whitcomb (1986) p. 24.

- ^ Davis (1995)pp. 67 – 68.

- ^ Williams (1987)

- ^ Tennison, John. "History of Boogie Woogie". Chapter 15. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ^ a b Kirchner (2005) p. 33.

- ^ Berlin (1994) p. 203.

- ^ Crawford (2001) p. 545.

- ^ a b Christensen (1999) p. 444.

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 203 – 204.

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 202 & 204.

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 207 – 208.

- ^ Berlin (1994) p. 202.

- ^ Kirk (2001) p. 194.

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 202 – 203.

- ^ "Pianola.co.nz". Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ^ Jasen & Tichenor (1978) p. 86.

- ^ a b Berlin (1994) p. 237.

- ^ "List of Piano Roll Artists". Pianola. Retrieved 2010-07-31.

- ^ Berlin (1994) pp. 237 & 239.

- ^ Blesh (1981) p.xxxix.

- ^ Siepmann (1998) p. 36.

- ^ Philip (1998) pp. 77 – 78.

- ^ Howat (1986) p. 160.

- ^ McElhone (2004) p. 26.

- ^ Rifkin, Joshua. Scott Joplin Piano Rags, Nonesuch Records (1970) album cover

- ^ Curtis (2004) p. 1.

- ^ Levin (2002) p. 197.

- ^ Jasen (1981) pp. 319 – 320.

- ^ Waldo (1976) pp. 179 – 182.

- ^ "Scott Joplin Piano Rags Nonesuch Records CD (w/bonus tracks)". Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ "Nonesuch Records". Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ Billboard Magazine 1974a, p. 61..

- ^ "Entertainment Awards Database". LA Times. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ^ a b Kronenberger, John (1974-08-11). "New York Times". The Ragtime Revival-A Belated Ode to Composer Scott Joplin.

- ^ Rich 1979, p. 81..

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C. (24 January 1971). "Scholars, Get Busy on Scott Joplin!". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- ^ Waldo (1976) p. 184.

- ^ "Entertainment Awards Database". LA Times. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ^ "Charis Music Group, compilation of cue sheets from the American Top 40 radio Show" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-09-05.

- ^ Billboard Magazine 1974b, p. 64.

- ^ Record World Magazine July 1974, quoted in Berlin (1994) p. 251.

- ^ a b Ping-Robbins 1998, p. 289.

- ^ a b Peterson, Bernard L. (1993). A century of musicals in black and white. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 357. ISBN 0-313-26657-3. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C. (13 February 1972). "The Scott Joplin Renaissance Grows". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- ^ "Birmingham Royal Ballet". Retrieved 2009-09-06.

- ^ "Songwriters Hall of Fame". Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ^ "The Pulitzer Prize – Special Awards and Citations". Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- ^ IMDB.com.

- ^ ESPER.

- ^ St. Louis Walk of Fame.

- ^ "2002 National Recording Registry from the National Recording Preservation Board of the Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2009-09-06.

Bibliography

Books

- Blesh, Rudi (1981). "Scott Jopin: Black-American Classicist". In Lawrence, Vera Brodsky (ed.). Scott Joplin Complete Piano Works. New York Public Library. ISBN 087104272X.

- Berlin, Edward A. (1994). King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era. Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0195101081.

- Crawford, Richard (2001). America's Musical Life: a History. W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0393048101.

- Curtis, Susan (1999). Christensen, Lawrence O (ed.). Dictionary of Missouri Biography. Univ. of Missouri Press. ISBN 0826212220. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- Curtis, Susan (2004). Dancing to a Black Man's Tune: A Life of Scott Joplin. Univ. of Missouri Press. ISBN 0826215475.

- Davis, Francis (1995). The History of the Blues:The Roots, the Music, the People. Hyperion. ISBN 0306812967.

- Gioia, Ted (1997). The History of Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509081-0.

- Haskins, James (1978). Scott Joplin. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-385-11155-X.

- Howat, Roy (1986). Debussy in Proportion: A Musical Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521311454. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- Jasen, David A. (1978). Rags and Ragtime: A Musical History. New York, NY: Dover Publications, Inc. p. 88. ISBN 0-486-25922-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Jasen, David A. (1981). "Discography of 78 rpm Records of Joplin Works". In Lawrence, Vera Brodsky (ed.). Scott Joplin Complete Piano Works. New York Public Library. ISBN 087104272X.

- Kirk, Elise Kuhl (2001). American Opera. Univ. of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252026233.

- Lawrence, Vera Brodsky, ed. (1971). Scott Joplin Complete Piano Works. New York Public Library. ISBN 0871042428.

- Levin, Floyd (2002). Classic Jazz: A Personal View of the Music and the Musicians. Univ. of California Press. ISBN 9780520234635.

- MaGee, Jeffrey (1998). "Ragtime and Early Jazz". In David Nicholls (ed.) (ed.). The Cambridge History of American Music. New York: The Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521454298.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - McElhone, Kevin (2004). Mechanical Music (2 ed.). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 0747805784. Retrieved 2009-04-16.

- Morath, Max (2005). Kirchner, Bill (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Jazz. Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0195183592.

- Palmer, Tony (1976). All You Need Is Love /The Story Of Popular Music. Book Club Associates. ISBN 9780670114481.

- Philip, Robert (1998). Rowland, David (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Piano (Illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052147986X. Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- Scott, William B.; Rutkoff, Peter M (2001). New York Modern: The Arts and the City. Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. ISBN 0801867932.

- Ping-Robbins, Nancy R. (1998). Scott Joplin: a guide to research. p. 289. ISBN 0-8240-8399-7. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Siepmann, Jeremy (1998). The Piano: The Complete Illustrated Guide to the World's Most Popular Musical Instrument. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 0793599768.

- Ryerson, Bill; Joplin, Scott (1973). Best of Scott Joplin: a Collection of Original Ragtime Piano Compositions. C. Hansen Music and Books. ISBN 0849405815.

- Waldo, Terry (1976). This Is Ragtime. New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc. ISBN 0-8015-7618-0.

- Waterman, Guy (1985a). "Ragtime". In J.E. Hasse (ed.) (ed.). Ragtime: Its History, Composers, and Music. New York: Shirmer Books. ISBN 0-02-871650-7.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Waterman, Guy (1985b). "Joplin's Late Rags: An Analysis". In J.E. Hasse (ed.) (ed.). Ragtime: Its History, Composers, and Music. New York: Shirmer Books. ISBN 0-02-871650-7.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Whitomb, Ian (1986). After the Ball. Hal Leonard Corp. ISBN 087910063X.

- Williams, Martin (1959). The Art of Jazz: Ragtime to Bebop. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0306801345.

- Williams, Martin, ed. (1987). The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 0393993426.

Web-pages

- Berlin, Edward A. (1998). "A Biography of Scott Joplin". The Scott Joplin International Ragtime Foundation. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Edwards, "Perfessor" Bill (2008). "Rags & Pieces by Scott Joplin, 1895 – 1905". Retrieved 2009-11-14.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Edwards, "Perfessor" Bill (2010). ""Perfessor" Bill's guide to notable Ragtime Era Composers". Retrieved 2011-07-28.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ESPER. "Black Heritage Stamp issues". Ebony Society of Philatelic Reflections, Inc. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - IMDB.com. "Listing for Scott Joplin (TV 1977)". IMDB.com, Inc. Retrieved 2011-08-16.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - RedHotJazz. "Wilbur Sweatman and His Band". Retrieved 2011-07-25.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - St. Louis Walk of Fame. "Inductees to the St. Louis Walk of Fame". St. Louis Walk of Fame. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Journals

- Albrecht, Theodore (1979). Julius Weiss: Scott Joplin's First Piano Teacher. Vol. 19. Case Western Univ. College Music Symposium. pp. 89–105.

- Billboard Magazine (1974a). "Best Selling Classical LPs". Billboard magazine (28th September 1974). Nielsen Business Media, Inc.: 61. Retrieved 2011-07-29.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Billboard Magazine (1974b). "Hot 100". Billboard Magazine (18th May 1974). Nielsen Business Media, Inc.: 64. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rich, Alan (1979). "Music". New York Magazine (24th December 1979). New York Media LLC: 81. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Texas State Historical Association – Biography of Scott Joplin

- The Scott Joplin International Ragtime Foundation

- Joplin at St. Louis Walk of Fame

- "Perfessor" Bill Edwards plays Joplin, with anecdotes and research.

- Maple Leaf Rag A site dedicated to 100 years of the Maple Leaf Rag.

- The Scott Joplin House – St. Louis, Missouri

- Scott Joplin at Find a Grave

Recordings and sheet music

- Free recordings of Joplin's music in Mp3 format by various pianists at PianoSociety.com

- www.kreusch-sheet-music.net – Free Scores by Joplin

- Sheet Music and Covers (includes cover art, comprehensive sheet music selection, and biography)

- Template:IckingArchive

- Free scores by Scott Joplin at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Kunst der Fuge: Scott Joplin – MIDI files (live and piano-rolls recordings)

- John Roache's site has MIDI performances of ragtime music by Joplin and others

- The Mutopia Project has compositions by Scott Joplin

- 1860s births

- 1917 deaths

- 20th-century classical composers

- African American classical composers

- African American pianists

- American classical musicians

- American composers

- Deaths from syphilis

- Music of St. Louis, Missouri

- People from St. Louis, Missouri

- People from Sedalia, Missouri

- People from Texarkana, Texas

- Ragtime composers

- Scott Joplin

- Songwriters Hall of Fame inductees

- Texas classical music