Natural logarithm

The natural logarithm is the logarithm to the base e, where e is an irrational and transcendental constant approximately equal to 2.718281828. The natural logarithm is generally written as ln(x), loge(x) or sometimes, if the base of e is implicit, as simply log(x).[1]

The natural logarithm of a number x is the power to which e would have to be raised to equal x. For example, ln(7.389...) is 2, because e2=7.389.... The natural log of e itself (ln(e)) is 1 because e1 = e, while the natural logarithm of 1 (ln(1)) is 0, since e0 = 1.

The natural logarithm can be defined for any positive real number a as the area under the curve y = 1/x from 1 to a. The simplicity of this definition, which is matched in many other formulas involving the natural logarithm, leads to the term "natural." The definition can be extended to non-zero complex numbers, as explained below.

The natural logarithm function, if considered as a real-valued function of a real variable, is the inverse function of the exponential function, leading to the identities:

Like all logarithms, the natural logarithm maps multiplication into addition:

Thus, the logarithm function is an isomorphism from the group of positive real numbers under multiplication to the group of real numbers under addition, represented as a function:

Logarithms can be defined to any positive base other than 1, not just e; however logarithms in other bases differ only by a constant multiplier from the natural logarithm, and are usually defined in terms of the latter. Logarithms are useful for solving equations in which the unknown appears as the exponent of some other quantity. For example, logarithms are used to solve for the half-life, decay constant, or unknown time in exponential decay problems. They are important in many branches of mathematics and the sciences and are used in finance to solve problems involving compound interest.

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| mathematical constant e |

|---|

|

| Properties |

| Applications |

| Defining e |

| People |

| Related topics |

History

The first mention of the natural logarithm was by Nicholas Mercator in his work Logarithmotechnia published in 1668,[2] although the mathematics teacher John Speidell had already in 1619 compiled a table on the natural logarithm.[3] It was formerly also called hyperbolic logarithm,[4] as it corresponds to the area under a hyperbola. It is also sometimes referred to as the Napierian logarithm, although the original meaning of this term is slightly different.

Notational conventions

Mathematicians, statisticians, and some engineers generally understand either "log(x)" or "ln(x)" to mean loge(x), i.e., the natural logarithm of x, and write "log10(x)" if the base 10 logarithm of x is intended.

Some engineers, biologists, and some others generally write "ln(x)" (or occasionally "loge(x)") when they mean the natural logarithm of x, and take "log(x)" to mean log10(x).

In most commonly-used programming languages, including C, C++, SAS, Fortran, and BASIC, "log" or "LOG" refers to the natural logarithm.

In hand-held calculators, the natural logarithm is denoted ln, whereas log is the base 10 logarithm.

In theoretical computer science, information theory, and cryptography "log(x)" generally means "log2(x)" (although this is often written as lg(x) instead).

Origin of the term natural logarithm

Initially, it might seem that since our numbering system is base 10, this base would be more "natural" than base e. But mathematically, the number 10 is not particularly significant. Its use culturally—as the basis for many societies’ numbering systems—likely arises from humans’ typical number of fingers.[5] Other cultures have based their counting systems on such choices as 5, 8, 12, 20, and 60.[6][7][8]

loge is a "natural" log because it automatically springs from, and appears so often in, mathematics. For example, consider the problem of differentiating a logarithmic function:[9]

If the base b equals e, then the derivative is simply 1/x, and at x = 1 this derivative equals 1. Another sense in which the base e logarithm is the most natural is that it can be defined quite easily in terms of a simple integral or Taylor series and this is not true of other logarithms.

Further senses of this naturalness make no use of calculus. As an example, there are a number of simple series involving the natural logarithm. Pietro Mengoli and Nicholas Mercator called it logarithmus naturalis a few decades before Newton and Leibniz developed calculus.[10]

Definitions

Formally, ln(a) may be defined as the area under the graph of 1/x from 1 to a, that is as the integral,

This defines a logarithm because it satisfies the fundamental property of a logarithm:

This can be demonstrated by letting as follows:

The number e can then be defined as the unique real number a such that ln(a) = 1.

Alternatively, if the exponential function has been defined first using an infinite series, the natural logarithm may be defined as its inverse function, i.e., ln is that function such that . Since the range of the exponential function on real arguments is all positive real numbers and since the exponential function is strictly increasing, this is well-defined for all positive x.

Properties

- (see complex logarithm)

Derivative, Taylor series

The derivative of the natural logarithm is given by

This leads to the Taylor series for around 0; also known as the Mercator series

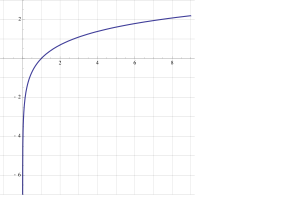

At right is a picture of ln(1 + x) and some of its Taylor polynomials around 0. These approximations converge to the function only in the region -1 < x ≤ 1; outside of this region the higher-degree Taylor polynomials are worse approximations for the function.

Substituting x − 1 for x, we obtain an alternative form for ln(x) itself, namely

By using the Euler transform on the Mercator series, one obtains the following, which is valid for any x with absolute value greater than 1:

This series is similar to a BBP-type formula.

Also note that is its own inverse function, so to yield the natural logarithm of a certain number y, simply put in for x.

The natural logarithm in integration

The natural logarithm allows simple integration of functions of the form g(x) = f '(x)/f(x): an antiderivative of g(x) is given by ln(|f(x)|). This is the case because of the chain rule and the following fact:

In other words,

and

Here is an example in the case of g(x) = tan(x):

Letting f(x) = cos(x) and f'(x)= - sin(x):

where C is an arbitrary constant of integration.

The natural logarithm can be integrated using integration by parts:

Numerical value

To calculate the numerical value of the natural logarithm of a number, the Taylor series expansion can be rewritten as:

To obtain a better rate of convergence, the following identity can be used.

- provided that y = (x−1)/(x+1) and x > 0.

For ln(x) where x > 1, the closer the value of x is to 1, the faster the rate of convergence. The identities associated with the logarithm can be leveraged to exploit this:

Such techniques were used before calculators, by referring to numerical tables and performing manipulations such as those above.

High precision

To compute the natural logarithm with many digits of precision, the Taylor series approach is not efficient since the convergence is slow. An alternative is to use Newton's method to invert the exponential function, whose series converges more quickly.

An alternative for extremely high precision calculation is the formula [12] [13]

where M denotes the arithmetic-geometric mean of 1 and 4/s, and

with m chosen so that p bits of precision is attained. (For most purposes, the value of 8 for m is sufficient.) In fact, if this method is used, Newton inversion of the natural logarithm may conversely be used to calculate the exponential function efficiently. (The constants ln 2 and π can be pre-computed to the desired precision using any of several known quickly converging series.)

Computational complexity

The computational complexity of computing the natural logarithm (using the arithmetic-geometric mean) is O(M(n) ln n). Here n is the number of digits of precision at which the natural logarithm is to be evaluated and M(n) is the computational complexity of multiplying two n-digit numbers.

Continued fractions

While no simple continued fractions are available, several generalized continued fractions are, including:

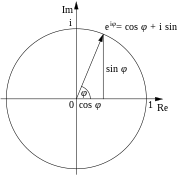

Complex logarithms

The exponential function can be extended to a function which gives a complex number as ex for any arbitrary complex number x; simply use the infinite series with x complex. This exponential function can be inverted to form a complex logarithm that exhibits most of the properties of the ordinary logarithm. There are two difficulties involved: no x has ex = 0; and it turns out that e2πi = 1 = e0. Since the multiplicative property still works for the complex exponential function, ez = ez+2nπi, for all complex z and integers n.

So the logarithm cannot be defined for the whole complex plane, and even then it is multi-valued – any complex logarithm can be changed into an "equivalent" logarithm by adding any integer multiple of 2πi at will. The complex logarithm can only be single-valued on the cut plane. For example, ln i = 1/2 πi or 5/2 πi or −3/2 πi, etc.; and although i4 = 1, 4 log i can be defined as 2πi, or 10πi or −6 πi, and so on.

- Plots of the natural logarithm function on the complex plane (principal branch)

-

z = Re(ln(x+iy))

-

z = Im(ln(x+iy))

-

Superposition of the previous 3 graphs

See also

- John Napier – inventor of logarithms

- Logarithm of a matrix

- Logarithmic integral function

- Nicholas Mercator - first to use the term natural log

- Polylogarithm

- Von Mangoldt function

- The number e

- Natural logarithm of 2

- Leonhard Euler

References

- ^ Mortimer, Robert G. (2005). Mathematics for physical chemistry (3rd ed.). Academic Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-125-08347-5., Extract of page 9

- ^ J J O'Connor and E F Robertson (2001-09). "The number e". The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Cajori, Florian (1991). A History of Mathematics, 5th ed. AMS Bookstore. p. 152. ISBN 0821821024.

- ^ Flashman, Martin. "Estimating Integrals using Polynomials". Retrieved 2008-03-23.

- ^ Boyers, Carl (1968). A History of Mathematics. Wiley.

- ^ Harris, John (1987). "Australian Aboriginal and Islander mathematics" (PDF). Australian Aboriginal Studies. 2: 29–37. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ^ Large, J.J. (1902). "The vigesimal system of enumeration". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 11 (4): 260–261. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1922). "Sexagesimal fractions among the Babylonians". American Mathematical Monthly. 29 (1): 8–10. doi:10.2307/2972914. JSTOR 2972914.

- ^ Larson, Ron (2007). Calculus: An Applied Approach (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 331. ISBN 0-618-95825-8., Section 4.5, page 331

- ^ Ballew, Pat. "Math Words, and Some Other Words, of Interest". Retrieved 2007-09-16.

- ^ "Logarithmic Expansions" at Math2.org

- ^ Sasaki, T.; Kanada, Y. (1982). "Practically fast multiple-precision evaluation of log(x)". Journal of Information Processing. 5 (4): 247–250. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^

Ahrendt, Timm (1999). "Stacs 99". Lecture notes in computer science. 1564: 302–312. doi:10.1007/3-540-49116-3_28. ISBN 978-3-540-65691-3.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help)