Abdul Karim (the Munshi)

Mohammed Abdul Karim | |

|---|---|

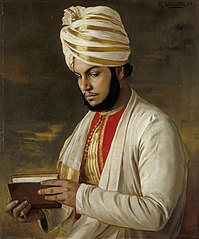

Portrait by Rudolf Swoboda, 1888 | |

| Indian Secretary to Queen Victoria | |

| In office 1892–1901 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1863 Lalatpur near Jhansi, British India |

| Died | April 1909 (aged 46) Agra, British India |

| Nationality | Indian (British subject) |

| Spouse | Rashidan Karim |

Hafiz Mohammed Abdul Karim (Hindi: हाफ़िज़ मुहम्मद अब्दुल करीम, Urdu: حافظ محمد عبدل کریم) CIE, CVO (1863–1909), known as "the Munshi", was a Muslim Indian attendant of Queen Victoria who gained her affection during the final fifteen years of her reign.

Karim was born near Jhansi in British India, the son of a hospital assistant. In 1887, Victoria's Golden Jubilee year, Karim was one of two Indians selected to become servants to the Queen. Victoria came to like him a great deal and gave him the title of "Munshi", a Hindi-Urdu word often translated as "clerk" or "teacher". Victoria appointed him her Indian Secretary, showered him with honours, and obtained a land grant for him in India.

The close relationship between Karim and the Queen led to friction within the Royal Household, the other members of which felt themselves to be superior to him. The Queen insisted on taking Karim with her on her travels, which caused angry arguments between her and her attendants. Following Victoria's death in 1901 her successor, Edward VII, returned Karim to India and ordered the confiscation and destruction of the Munshi's correspondence with Victoria. Karim subsequently lived quietly near Agra, on the estate that Victoria had arranged for him, until his death at the age of 46.

Early life

Karim was born into a Muslim family at Lalitpur near Jhansi in 1863.[1] His father, Haji Mohammed Waziruddin, was a hospital assistant stationed with the Central India Horse, a British cavalry regiment.[2] Karim had one older brother, Abdul Aziz, and four younger sisters. He was taught Persian and Urdu privately,[3] and as a teenager travelled across North India and into Afghanistan.[4] Karim's father participated in the conclusive march to Kandahar, which ended the Second Anglo-Afghan War, in August 1880. After the war, Karim's father transferred from the Central India Horse to a civilian position at the Central Jail in Agra, while Karim worked as a vakil ("agent" or "representative") for the Nawab of Jawara in the Agency of Agar. After three years in Agar, Karim resigned and moved to Agra, to become a vernacular clerk at the jail. His father arranged a marriage between Karim and the sister of a fellow worker.[5]

Prisoners in the Agra jail were trained and kept employed as carpet weavers as part of their rehabilitation. In 1886, 34 convicts travelled to London to demonstrate carpet weaving at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in South Kensington. Karim did not accompany the prisoners, but assisted Jail Superintendent John Tyler in organising the trip, and helped to select the carpets and weavers. When Queen Victoria visited the exhibition, Tyler gave her a gift of two gold bracelets, again chosen with the assistance of Karim.[6] The Queen had a longstanding interest in her Indian territories and wished to employ some Indian servants for her Golden Jubilee. She asked Tyler to recruit two attendants who would be employed for a year.[7] Karim was hastily coached in British manners and in the English language and sent to England, along with Mohammed Buksh. Major-General Thomas Dennehy, who was about to be appointed to the Royal Household, had previously employed Buksh as a servant.[8] It was planned that the two Indian men would initially wait at table, and learn to do other tasks.[9]

ROyal cosa????

Royal è una strada bagnata per la quale gli organismi si divertono a cagare intorno costruendo la torre effeile

Household hostility

In November 1888, Karim was given four months leave to return to India, during which time he visited his father. Karim wrote to Victoria that his father, who was due to retire, had hopes of a pension, and that his former employer, John Tyler, was angling for promotion. As a result, throughout the first six months of 1889, Victoria wrote to the Viceroy of India, Lord Lansdowne, demanding action on Waziruddin's pension and Tyler's promotion. The Viceroy was reluctant to pursue the issues because Waziruddin had told the local governor, Sir Auckland Colvin, that he desired only gratitude, and Tyler had a reputation for tactless behaviour and bad-tempered remarks.[10][11]

Karim's swift rise began to create jealousy and discontent among the members of the Royal Household, who would normally never mingle socially with Indians below the rank of prince. The Queen expected them to welcome Karim, an Indian of ordinary origin, into their midst; they were not willing to do so.[12] Karim, for his part, expected to be treated as an equal. When Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), hosted an entertainment for the Queen at his home in Sandringham on 26 April 1889, Karim found he had been allocated a seat with the servants. Feeling insulted, he retired to his room. The Queen took his part, stating that he should have been seated among the Household.[13] When the Queen attended the Braemar Games in 1890, her son, Arthur, Duke of Connaught, approached the Queen's private secretary Sir Henry Ponsonby in outrage after he saw the Munshi among the gentry. Ponsonby suggested that as it was "by the Queen's order" the Duke should approach the Queen about it.[14] "This entirely shut him up", noted Ponsonby.[15]

Victoria biographer Carolly Erickson described the situation:

The rapid advancement and personal arrogance of the Munshi would inevitably have led to his unpopularity, but the fact of his race made all emotions run hotter against him. Racialism was a scourge of the age; it went hand in hand with belief in the appropriateness of Britain's global dominion. For a dark-skinned Indian to be put very nearly on a level with the queen's white servants was all but intolerable, for him to eat at the same table as them, to share in their daily lives was viewed as an outrage. Yet the queen was determined to impose harmony on her household. Race hatred was intolerable to her, and the "dear good Munshi" deserving of nothing but respect.[16]

When complaints were brought to her, Victoria refused to believe any negative comments about Karim.[17] She dismissed concerns about his behaviour, deemed high-handed by Household and staff, as "very wrong".[18] In June 1889, Karim's brother-in-law, Hourmet Ali, sold one of Victoria's brooches to a jeweller in Windsor. She accepted Karim's explanation that Ali had found the brooch and that it was customary in India to keep anything found as one's own, whereas the rest of the Household thought Ali had stolen it.[19] In July, Karim was assigned the room previously occupied by Dr (later Sir) James Reid, Victoria's physician, and given the use of a private sitting room.[20]

The Queen, influenced by the Munshi, continued to write to Lord Lansdowne on the issue of Tyler's promotion and the administration of India. She expressed reservations on the introduction of elected councils on the basis that Muslims would not win many seats because they were in the minority, and urged that Hindu feasts be re-scheduled so as not to conflict with Muslim ones. Lansdowne dismissed the latter suggestion as potentially divisive,[21] but appointed Tyler Acting Inspector General of Prisons in September 1889.[22]

To the Household's surprise, and concern, during Victoria's stay at Balmoral in September 1889, she and Karim stayed for one night at a remote house on the estate, Glassalt Shiel at Loch Muick. Victoria had often been there with Brown, and had sworn never to stay there after his death.[22] In early 1890, Karim fell ill with an inflamed boil on his neck, and Victoria instructed Reid, her physician, to attend to Karim.[23] She wrote to Reid expressing her anxiety and explaining that she felt responsible for the welfare of her Indian servants because they were so far from their own land.[24] Reid performed an operation to open and drain the swelling, and Karim recovered.[24] Reid wrote on 1 March 1890 that the Queen was "visiting Abdul twice daily, in his room taking Hindustani lessons, signing her boxes, examining his neck, smoothing his pillows, etc."[25]

Later life

In late 1898 Karim's purchase of a parcel of land adjacent to his earlier grant was finalised; he had become a wealthy man.[26] Reid claimed in his diary that he had challenged Karim over his financial dealings: "You have told the Queen that in India no receipts are given for money, and therefore you ought not to give any to Sir F Edwards [Keeper of the Privy Purse]. This is a lie and means that you wish to cheat the Queen."[27] The Munshi told the Queen he would provide receipts in answer to the allegations, and Victoria wrote to Reid dismissing the accusations, calling them "shameful".[28]

Karim asked Victoria to make him a "nawab", the Indian equivalent of a peer, and to give him a knighthood in the Order of the Indian Empire. A horrified Elgin suggested instead that she make Karim a Member of the Royal Victorian Order (MVO), which was in her personal gift, bestowed no title, and would have little political implication in India.[29] Privy Purse Sir Fleetwood Edwards and Prime Minister Lord Salisbury advised against even the lower honour.[30] Nevertheless in 1899, on the occasion of her 80th birthday, Victoria appointed Karim a commander of the order (CVO), a rank intermediate between member and knight.[31]

The Munshi returned to India in November 1899 for a year. Waziruddin, described as "a courtly old gentleman" by Lord Curzon, Elgin's replacement as Viceroy, died in June 1900.[32] By the time Karim returned to Britain in November 1900 Victoria had visibly aged, and her health was failing. Within three months she was dead.[33]

After Victoria's death her son, King Edward VII, dismissed the Munshi and his relations from court and had them sent back to India. However, Edward did allow the Munshi to be the last to view Victoria's body before her casket was closed,[34] and to be part of her funeral procession.[35] Almost all of the correspondence between Victoria and Karim was burned on Edward's orders.[36] Lady Curzon wrote on 9 August 1901,

Charlotte Knollys told me that the Munshi bogie which had frightened all the household at Windsor for many years had proved a ridiculous farce, as the poor man had not only given up all his letters but even the photos signed by Queen and had returned to India like a whipped hound. All the Indian servants have gone back so now there is no Oriental picture & queerness at Court.[37]

In 1905–06, George, Prince of Wales, visited India and wrote to the King from Agra, "In the evening we saw the Munshi. He has not grown more beautiful and is getting fat. I must say he was most civil and humble and really pleased to see us. He wore his C.V.O. which I had no idea he had got. I am told he lives quietly here and gives no trouble at all."[38]

The Munshi died at his home, Karim Lodge, on his estate in Agra in 1909.[39] He was survived by two wives,[40] and was interred in a pagoda-like mausoleum in the Panchkuin Kabaristan cemetery in Agra beside his father.[41]

On the instructions of Edward VII, the Commissioner of Agra, W. H. Cobb, visited Karim Lodge to retrieve any remaining correspondence between the Munshi and the Queen or her Household, which was confiscated and sent to the King.[42] The Viceroy (by then Lord Minto), Lieutenant-Governor John Hewitt, and India Office civil servants disapproved of the seizure, and recommended that the letters be returned.[43] Eventually the King returned four, on condition that they would be sent back to him on the death of the Munshi's first wife.[44]

Legacy

Until the publication of Frederick Ponsonby's memoirs in 1951, there was little biographical material on the Munshi.[45] Scholarly examination of his life and relationship with Victoria began around the 1960s,[46] focusing on the Munshi as "an illustration of race and class prejudice in Victorian England".[47] Mary Lutyens, in editing the diary of her grandmother Edith (wife of Lord Lytton, Viceroy of India 1876–80), concluded, "Though one can understand that the Munshi was disliked, as favourites nearly always are ... One cannot help feeling that the repugnance with which he was regarded by the Household was based mostly on snobbery and colour prejudice."[48] Elizabeth Longford wrote, "Abdul Karim stirred once more that same royal imagination which had magnified the virtues of John Brown ... Nevertheless, [it] insinuated into her confidence an inferior person, while it increased the nation's dizzy infatuation with an inferior dream, the dream of Colonial Empire."[49]

Historians agree with the suspicions of her Household that the Munshi influenced the Queen's opinions on Indian issues, biasing her against Hindus and favouring Muslims.[50] But suspicions that he passed secrets to Rafiuddin Ahmed are discounted. Victoria asserted that "no political papers of any kind are ever in the Munshi's hands, even in her presence. He only helps her to read words which she cannot read or merely ordinary submissions on warrants for signature. He does not read English fluently enough to be able to read anything of importance."[51] Consequently, it is thought unlikely that he could have influenced the government's Indian policy or provided useful information to Muslim activists.[47]

Notes and references

- ^ Basu, p. 22

- ^ Basu, pp. 22–23

- ^ Basu, p. 23

- ^ Basu, pp. 23–24

- ^ Basu, p. 24

- ^ Basu, p. 25

- ^ Victoria to Lord Lansdowne, 18 December 1890, quoted in Basu. p. 87

- ^ Basu, pp. 26–27

- ^ Anand, p. 13

- ^ Basu, pp. 68–69

- ^ Victoria herself acknowledged that "he is a very irascible man, with a violent temper and a total want of tact, and his own enemy, but v.kind-hearted and hospitable, a very good official, and a first-rate physician", to which Lansdowne replied, "Your Majesty has summed up that gentleman's strong and weak points in language which exactly meets the case." (Quoted in Basu, p. 88)

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

a18was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Anand, pp. 18–19; Basu, pp. 70–71

- ^ Waller, p. 441

- ^ Basu, p. 71; Hibbert, p. 448

- ^ Erickson, Carolly (2002) Her Little Majesty, New York: Simon and Shuster, p. 241. ISBN 0-7432-3657-2. Paragraph break omitted after third sentence.

- ^ Basu, pp. 70–71

- ^ Victoria to Dr Reid, 13 May 1889, quoted in Basu, p. 70

- ^ Anand, pp. 20–21; Basu, pp. 71–72

- ^ Basu, p. 72

- ^ Basu, pp. 73, 109–110

- ^ a b Basu, p. 74

- ^ Basu, p. 75

- ^ a b Basu, p. 76

- ^ Quoted in Anand, p. 22 and Basu, p. 75

- ^ Basu, pp. 173, 192

- ^ Reid's diary, 4 April 1897, quoted in Basu, pp. 145–146 and Nelson, p. 110

- ^ Quoted in Basu, p. 161

- ^ Basu, pp. 150–151

- ^ Basu, p. 156

- ^ "No. 27084". The London Gazette. 30 May 1899.

- ^ Basu, pp. 178–179

- ^ Basu, pp. 180–181

- ^ Basu, p. 182; Hibbert, pp. 498; Rennell, p. 187

- ^ Anand, p. 102

- ^ Anand, p. 96; Basu, p. 185; Longford, pp. 541–542

- ^ Quoted in Anand, p. 102

- ^ Quoted in Anand, pp. 103–104 and Basu, p. 192

- ^ Basu, p. 193

- ^ Basu, p. 198

- ^ Basu, p. 19

- ^ Basu, pp. 197–199

- ^ Basu, pp. 200–201

- ^ Basu, p. 202

- ^ Longford, p. 535

- ^ Longford, p. 536

- ^ a b Visram, Rozina (2004) "Karim, Abdul (1862/3–1909)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/42022 (Subscription required for online access)

- ^ Lutyens, Mary (1961) Lady Lytton's Court Diary 1895–1899, London: Rupert Hart-Davis, p. 42

- ^ Longford, p. 502

- ^ e.g. Longford, p. 541; Plumb, p. 281

- ^ Victoria to Salisbury, 17 July 1897, quoted in Longford, p. 540

Bibliography

- Anand, Sushila (1996) Indian Sahib: Queen Victoria's Dear Abdul, London: Gerald Duckworth & Co., ISBN 0-7156-2718-X

- Basu, Shrabani (2010) Victoria and Abdul: The True Story of the Queen's Closest Confidant, Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, ISBN 978-0-7524-5364-4

- Hibbert, Christopher (2000) Queen Victoria: A Personal History, London: HarperCollins, ISBN 0-00-638843-4

- Longford, Elizabeth (1964) Victoria R.I., London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 0-297-17001-5

- Nelson, Michael (2007) Queen Victoria and the Discovery of the Riviera, London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks, ISBN 978-1-84511-345-2

- Plumb, J. H. (1977) Royal Heritage: The Story of Britain's Royal Builders and Collectors, London: BBC, ISBN 0-563-17082-4

- Rennell, Tony (2000) Last Days of Glory: The Death of Queen Victoria, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-30286-X

- Waller, Maureen (2006) Sovereign Ladies: The Six Reigning Queens of England, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-33801-5

External links

- Queen Victoria and Abdul: Diaries reveal secrets, BBC News, 14 March 2011.