In Flanders Fields

"In Flanders Fields" is one of the most notable poems written during World War I, created in the form of a French rondeau. It has been called "the most popular poem" produced during that period.[1] Canadian physician and Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae wrote it on 3 May 1915 (see 1915 in poetry), after he witnessed the death of his friend, Lieutenant Alexis Helmer, 22 years old, the day before. The poem was first published on 8 December of that year in the London-based magazine Punch.

Historical context

The poppies referred to in the poem grew in profusion in Flanders in the disturbed earth of the battlefields and cemeteries where war casualties were buried[2] and thus became a symbol of Remembrance Day (see Remembrance poppy). The poem is often part of Remembrance Day solemnities in Allied countries which contributed troops to World War I, particularly in countries of the British Empire that did so.

The poem "In Flanders Fields" was written after John McCrae witnessed the death, and presided over the funeral, of a friend, Lt. Alexis Helmer.[3] By most accounts it was written in his notebook[4] and later rejected by McCrae. Ripped out of his notebook, it was rescued by a fellow officer, Francis Alexander Scrimger, and later published in Punch magazine. However, this story is rejected by the editor at the time:

"A legend has already grown up around the publication of "In Flanders Fields" in Punch. The truth is, 'that the poem was offered in the usual way and accepted; that is all.' The usual way of offering a piece to an editor is to put it in an envelope with a postage stamp outside to carry it there, and a stamp inside to carry it back. Nothing else helps."[5]

Poem

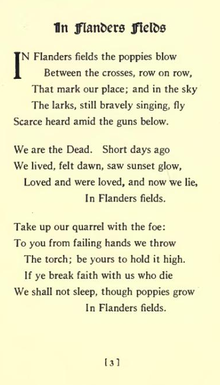

The first chapter of In Flanders Fields and Other Poems (a 1919 collection of poems by John McCrae) gives the text of the poem as follows:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

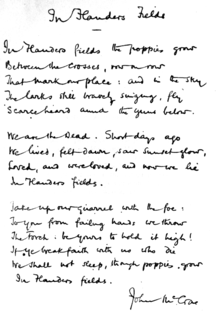

An autographed copy of the poem (reproduced at the start of this same book) uses grow (instead of blow) in the first line. The book includes a note seeking to explain the discrepancy by saying "This was probably written from memory".

Status

In 1918 US professor Moina Michael, inspired by the poem, published a poem of her own in response, called We Shall Keep the Faith.[6] In tribute to the opening lines of McCrae's poem — "In Flanders fields the poppies blow / Between the crosses row on row," — Michael vowed to always wear a red poppy as a symbol of remembrance for those who served in the war.[7]

The poem has achieved near-mythical status in contemporary Canada and is one of the nation's most prominent symbols.[citation needed] Most Remembrance Day ceremonies will feature a reading of the poem in some form (it is also sung in some places), and many Canadian school children memorize the verse. A quotation from the poem appears on the Canadian ten-dollar bill. The poem is part of Remembrance Day ceremonies in the United Kingdom, where it holds as one of the nation's best-loved, and is occasionally featured in Memorial Day ceremonies in the United States.[citation needed]

The poem is printed in materials published by veterans' organizations in Canada[8] and the United States.[9]

The use of "grow" in the first line appears in a handwritten and autographed copy for the 1919 edition of McCrae's poems; the editor, Andrew Macphail, notes in the caption, "This was probably written from memory as "grow" is used in place of "blow" in the first line." [5] However, a tracing of a holograph copy on the letterhead of Captain Gilbert Tyndale-Lea M.C. now held by the Imperial War Museum claims that the original dates from 29 April 1915 and that it was given to the captain by the poet on that date. This clearly shows 'grow' in the first line and would change the publicly-held belief as to its date of composition and original first line.[10] This was certainly changed by the time he submitted it to Punch for publication in December of that year. Whether McCrae originally wrote 'grow' or 'blow' in the first line might never clearly be established.[citation needed]

Criticisms

Critic Paul Fussell, in The Great War and Modern Memory, claimed to find sharp distinctions between the pastoral, sacrificial tone of the poem's first nine lines and the "recruiting-poster rhetoric" of the poem's third stanza. Fussell said the poem, first appearing in the 1915 context of the early stages of World War I, would have, at that time, served to denigrate any negotiated peace which would end the war. In this context, Fussel called these lines "a propaganda argument," saying "words like vicious and stupid would not seem to go too far."[11]

Other versions

An illustrated edition of the poem was published in 1921, with a preface by William Thomas Manning.[12]

An official adaptation into French, used by the Canadian government in Remembrance Day ceremonies, was written by Jean Pariseau and is entitled Au champ d'honneur.[citation needed]

Musical settings

"In Flanders Fields" is sung, rather than recited, every year at the televised national Remembrance Day service at Ottawa, Canada. The musical setting that has been used for many years is the Soprano and Alto version of a composition by a Canadian, Alexander Tilley. Tilley's setting of the poem also exists in a full choral arrangement for S.A.T.B. chorus with pianoforte accompaniment.

American composer, Charles Ives composed a version of "In Flanders Fields." It appears in the 114 Songs collection that was published in 1922.

On their 1979 album Join Hands rock band Siouxsie & the Banshees used the first lines of the poem for the song "Poppy Day".

See also

Notes

- ^ Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory, Oxford University Press, 2000, (ISBN 0195133323), p. 248.

- ^ The tendency of red poppies to grow on the fresh graves of soldiers in the fields of northern Europe has been noted at least from Napoleonic times. See The History and Poetry of "In Flanders Fields".

- ^ "Casualty Details Helmer, Alexis Hannum". Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

- ^ Michael Robert Patterson. "Arlingtoncemetery.net". Arlingtoncemetery.net. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ a b Macphail, Andrew (1919). "John McCrae: An essay in character". In Flanders Fields and Other Poems.

- ^ "Moina Michael". Digital Library of Georgia/University of Georgia. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ^ "Where did the idea to sell poppies come from?". BBC News. 10 November 2006. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ^ Teachers' Guide, Royal Canadian Legion, p. 20.

- ^ "Buddy Poppy", Veterans of Foreign Wars.

- ^ First World War Poetry Archive, http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/collections/item/1643 c.f. Imperial War Museum Record

- ^ Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modern Memory, Oxford University Press, 2000, (ISBN 0195133323), pp. 249-250.

- ^ McCrae, John (1921). In Flanders Fields. William Thomas Manning, Ernest Clegg (illustrations) (limited edition ed.). William Edwin Rudge.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)

Further reading

- McCrae, Lieutenant Colonel John (1919), In Flanders Fields and Other Poems, Arcturus Publishing (reprint 2008), ISBN 1841939943

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help)

External links

- Free audiobook from LibriVox

- This site contains an account of the writing of the poem and a facsimile of the author's manuscript.

- In Flanders Fields, the website of the museum of this name in Ypres, dedicated to this poem

- Royal Canadian Legion web page about John McCrae, In Flanders Fields, and the custom of wearing poppies

- In Flanders Fields, choral piece by composer Bradley Nelson, commissioned by Fresno State Chamber Singers and Chico State Chamber Singers of California State University

- Lost Poets of the Great War, a hypertext document on the poetry of World War I by Harry Rusche, of the English Department, Emory University, Atlanta Georgia. It contains a bibliography of related materials.