Retrofuturism

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2008) |

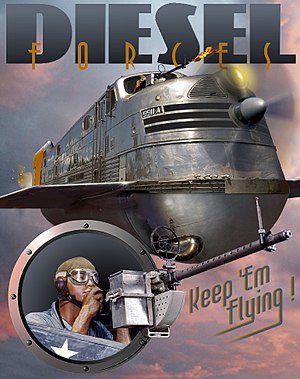

Retro-futurism (adjective retro-futuristic or retro-future) is a trend in the creative arts showing the influence of depictions of the future produced prior to about 1960.[1] Characterized by a blend of old-fashioned "retro" styles with futuristic technology, retro-futurism explores the themes of tension between past and future, and between the alienating and empowering effects of technology. Primarily reflected in artistic creations and modified technologies that realize the imagined artifacts of its parallel reality, retro-futurism has also manifested in the worlds of fashion, architecture, literature and film.

Etymology

The word "retrofuturism" was coined by Lloyd Dunn[2] in 1983,[3] according to fringe art magazine Retrofuturism, which was published from 1988-1993.[4]

Characteristics

Retro-futurism incorporates two overlapping trends which may be summarized as the future as seen from the past and the past as seen from the future.

The first trend, retro-futurism proper, is directly inspired by the imagined future which existed in the minds of writers, artists, and filmmakers in the pre-1960 period who attempted to predict the future, either in serious projections of existing technology (e.g. in magazines like Science and Invention) or in science fiction novels and stories. Such futuristic visions are refurbished and updated for the present, and offer a nostalgic, counterfactual image of what the future might have been, but is not.

The second trend is the inverse of the first: futuristic retro. It starts with the retro appeal of old styles of art, clothing, mores, and then grafts modern or futuristic technologies onto it, creating a mélange of past, present, and future elements. Steampunk, a term applying both to the retrojection of futuristic technology into an alternative Victorian age, and the application of neo-Victorian styles to modern technology, is a highly successful version of this second trend.

In practice, the two trends cannot be sharply distinguished, as they mutually contribute to similar visions. Retro-futurism of the first type is inevitably influenced by the scientific, technological, and social awareness of the present, and modern retro-futuristic creations are never simply copies of their pre-1960 inspirations; rather, they are given a new (often wry or ironic) twist by being seen from a modern perspective.

In the same way, futuristic retro owes much of its flavor to early science fiction (e.g. the works of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells), and in a quest for stylistic authenticity may continue to draw on writers and artists of the desired period.

Both retro-futuristic trends in themselves refer to no specific time. When a time period is supplied for a story, it might be a counterfactual present with unique technology; a fantastic version of the future; or an alternate past in which the imagined (fictitious or projected) inventions of the past were indeed real. Examples include the film Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, set in an imaginary 1939, and The Rocketeer franchise, set in 1938.

Themes

Although retro-futurism, due to the varying time-periods and futuristic visions to which it alludes, does not provide a unified thematic purpose or experience, a common thread is dissatisfaction or discomfort with the present, to which retro-futurism provides a nostalgic contrast.

One such theme is dissatisfaction with modern futurism. In some respects, an extrapolation of the present to the future produces disappointing, or even ghastly results, exemplified in cyberpunk and other dystopian futures characterized by overpopulation, environmental degradation, and transfer of power to unaccountable private entities or governments. Compared to such a future, retro-futurism suggests a world which may be more comfortable or at least more capable of being understood.

A similar theme is dissatisfaction with the modern world itself. A world of high-speed air transport, computers, and space stations is (by any past standard) 'futuristic'; yet the search for alternative and perhaps more promising futures suggests a feeling that the desired or expected future has failed to materialize. Retro-futurism suggests an alternative path, and in addition to pure nostalgia, may act as a reminder of older but now forgotten ideals.

Retro-futurism also implies a re-evaluation of technology. Unlike the total rejection of post-medieval technology found in fantasy genres, or the embrace of any and all possible technologies found in some science-fiction, retro-futurism calls for a human-scale, largely comprehensible technology, amenable to tinkering and less opaque than modern black-box technology.

Retro-futurism is not universally optimistic, and when its points of reference touch on gloomy periods like World War II, or the paranoia of the Cold War, it may itself become bleak and dystopian. In such cases, the alternative reality inspires fear, not hope, though it may still be coupled with nostalgia for a world of greater moral as well as mechanical transparency.

Design and arts

A great deal of attention is drawn to fantastic machines, buildings, cities, and transportation systems. The futuristic design aesthetic of the early 20th century tends to solid colors, streamlined shapes, and mammoth scales. It might be said that 20th century futuristic vision found its ultimate expression in the development of Googie or Populuxe design. As applied to fiction, this brand of retro-futuristic visual style is also referred to as Raygun Gothic, a catchall term for a visual style that incorporates various aspects of the Googie, Streamline Moderne, and Art Deco architectural styles when applied to retro-futuristic science fiction environments.

Although Raygun Gothic is most similar to the Googie or Populuxe style and sometimes synonymous with it, the name is primarily applied to images of science fiction. The style is also still a popular choice for retro sci-fi in film and video games.[5] Raygun Gothic's primary influences include the set designs of Kenneth Strickfaden and Fritz Lang.[citation needed] The term was coined by William Gibson in his story "The Gernsback Continuum": "Cohen introduced us and explained that Dialta [a noted pop-art historian] was the prime mover behind the latest Barris-Watford project, an illustrated history of what she called "American Streamlined Modern." Cohen called it "raygun Gothic." Their working title was The Airstream Futuropolis: The Tomorrow That Never Was."[6]

Fashion

Futuristic clothing is a particular imagined vision of the clothing that might be worn in the distant future, typically found in science fiction and science fiction films of the 1940s onwards, but also in journalism and other popular culture. The garments envisioned have most commonly been either one-piece garments, skin-tight garments, or both, typically ending up looking like either overalls or leotards, often worn together with plastic boots. In many cases, there is an assumption that the clothing of the future will be highly uniform.

The cliché of futuristic clothing has now become part of the idea of retro-futurism. Futuristic fashion plays on these now-hackneyed stereotypes, and recycles them as elements into the creation of real-world clothing fashions.

"We've actually seen this look creeping up on the runway as early as 1995, though it hasn't been widely popular or acceptable street wear even through 2008," said Brooke Kelley, fashion editor and Glamour magazine writer. "For the last 20 years, fashion has reviewed the times of past, decade by decade, and what we are seeing now is a combination of different eras into one complete look. Future fashion is a style beyond anything we've yet dared to wear, and it's going to be a trend setter's paradise."

Architecture

Retro-futurism has appeared in some examples of postmodern architecture. In the example seen at right, the upper portion of the building is not intended to be integrated with the building but rather to appear as a separate object—a huge flying saucer-like space ship only incidentally attached to a conventional building. This appears intended not to evoke an even remotely possible future, but rather a past imagination of that future, or a reembracing of the futuristic vision of Googie architecture.

Los Angeles International Airport and its Theme Building in Los Angeles was built in 1961 as a way to commemorate the optimism of the new jet and space age and also displayed the Googie and Populuxe designs. The Theme Building (now a restaurant) was listed as a City Cultural and Historical Monument by the Los Angeles city council in 1992 and was recently refurbished by Walt Disney Imagineering in 1997. Current designs for LAX's expansion in 2012 will have the same recurring flying-saucer/spaceship themes in the new terminals and concourses.

See also

References

- ^ Jenkins, Henry. "The Tomorrow That Never Was: Retrofuturism in the Comics of Dean Motter", Confessions of an Aca-Fan, 2007

- ^ Paul McFedries (2000-12-13). "retrofuturism". Word Spy. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ^ Retrofuturism

- ^ "PSRF Retrograde Archive : p28". Psrf.detritus.net. Retrieved 2009-05-08.

- ^ Sharon Ross (June 8th, 2009). "Retro Futurism At Its Best: Designs and Tutorials". Smashing Magazine.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Gernsback Continuum" in Gibson, William (1986). Burning Chrome. New York: Arbor House. ISBN 9780877957805.

Further reading

- Kilgore, De Witt Douglas (2003). Astrofuturism: Science, Race, and Visions of Utopia in Space. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1847-7.

- Heimann, Jim (2002). Future Perfect. Köln, London: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-1566-7.

- Brosterman, Norman. Out of Time: Designs for the Twentieth Century Future. ISBN 0-8109-2939-2.

- Corn, Joseph J. (1996). Yesterday's Tomorrows: Past Visions of the American Future. JHU Press. ISBN 0-8018-5399-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Canto, Christophe (1993). The History of the Future: Images of the 21st Century. Flammarion. ISBN 2-08-013544-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Futuropolis: Impossible Cities of Science Fiction and Fantasy. ISBN 0-903767-22-8.

- Hodge, Brooke (2002). Retrofuturism: The Car Design of J Mays. Museum of Contemporary Art. ISBN 0-7893-0822-3.

- Onosko, Tim (1979). Wasn't the Future Wonderful?: A View of Trends and Technology From the 1930s. Dutton. ISBN 0525475516.

- Wilson, Daniel H. (2007). Where's My Jetpack?: A Guide to the Amazing Science Fiction Future that Never Arrived. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 1-59691-136-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

External links

- The wonder city you may live to see - 1950 as seen in 1925