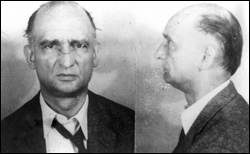

Rudolf Abel

Vilyam Genrikhovich Fisher | |

|---|---|

Soviet intelligence officer Rudolf Abel on the 1990 USSR commemorative stamp | |

| Born | July 11, 1903[8] |

| Died | November 16, 1971 (aged 68)[10] |

| Cause of death | lung cancer |

| Burial place | Moscow, Soviet Union[11] |

| Nationality | |

| Spouse | Elena[12] |

| Children | Evelyn[12] |

| Espionage activity | |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Codename | Andrew Yurgesovich Kayotis[2] |

| Codename | Emil Robert Goldfus[2] |

| Codename | Mark Collins[3] |

| Codename | MARK[4] |

| Codename | Rudolf Ivanovich Abel[5] |

| Operations | World War II Soviet Cold War spy (1948–1957) |

Vilyam "Willie" Genrikhovich Fisher (Russian: Вильям "Вилли" Генрихович Фишер) (July 11, 1903 – November 16, 1971) was a Soviet intelligence officer. Fisher is generally better known by the alias Rudolf Ivanovich Abel, which he adopted when arrested on charges of conspiracy by FBI agents in 1957.

Born in the United Kingdom to Russian émigré parents, after moving to Russia in the 1920s, Fisher served in the Soviet military before undertaking foreign service as a radio operator in Soviet intelligence in the late 1920s and early 1930s. He later served in an instructional role before taking part in intelligence operations against the Germans during World War II. After the war, Fisher began working for the KGB, which sent him to the United States where he worked as part of a spy ring based in New York.

In 1957, for his involvement in what became known as the Hollow Nickel Case, the U.S. Federal Court in New York convicted Fisher on three counts of conspiracy as a Soviet spy and sentenced him to 45 years' imprisonment at Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, Georgia.[13] However, Fisher had only served just over four years of his sentence when, on February 10, 1962, he was exchanged for captured American U-2 pilot Gary Powers. Upon his return to the Soviet Union Fisher was reunited with his family and lectured on his experiences before dying in 1971 at the age of 68.

Early life

Fisher was born on July 11, 1903, in Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom. His parents, ethnic Germans from Russia, were revolutionaries of the Tsarist era, and had fled to the United Kingdom in 1901.[4] His father, Heinrich, a keen Bolshevik, whilst living in England took part in gunrunning, shipping arms from the North East coast to the Baltic states to help the proletariat.[8]

In 1918, at the age of 15, Fisher became an apprentice draughtsman at Swan Hunter Wallsend, and attended evening classes at Rutherford College before being accepted into London University in 1919.[14] The Fisher family left Newcastle upon Tyne in 1921, to return to Moscow, following the 1917 Russian revolution.[15]

Early career

After the family's return to Russia in 1921, Fisher worked for Comintern as a translator, as his lingual fluencies included English, Russian, German, Polish and Yiddish.[1] During his military service in the Red Army, 1925–1926, he was trained as a radio operator.[15] He worked briefly in GRU and was then recruited by the OGPU, a predecessor of the KGB, in 1927. He worked for them as a radio operator in Norway, Turkey, Britain, and France then returned to Russia in 1936, as head of a school which trained radio operators destined for duty in illegal residences.[16] One of these students was the British-born Russian spy Kitty Harris, who was later more widely known as "The Spy With Seventeen Names".[17]

Despite being born in the United Kingdom, and the accusation that his brother-in-law was a Trotskyite, Fisher narrowly escaped the Great Purge, which took place during 1936–1938. He escaped prosecution but was dismissed from the NKVD in 1938. During World War II he again trained radio operators for clandestine work behind German lines.[4] Having been adopted as a protégé of Pavel Sudoplatov, Fisher was involved in August 1944 in Operation Scherhorn (Russian: Операция Березино). Sudoplatov later described this operation as "the most successful radio deception game of the war." In the view of Fisher's bosses in the KGB, his part in this operation was rewarded with the most important posting in Russian foreign intelligence, this being the United States.[18]

In the Secret service

In 1946, Fisher again entered the KGB, and was trained as a spy for entry into the United States. In October 1948, using a Soviet passport, he travelled from Leningradsky Station to Warsaw, Poland. He then travelled, via Czechoslovakia and Switzerland to Paris, France. His passport bore the name Andrew Kayotis, the first of Fisher's fake identities. The real Andrew Kayotis (Lithuanian: Ąndręi Yųrgęsovįčh Kąyotis) was Lithuanian born, and had become an American citizen after migrating to the U.S. Kayotis conveniently disappeared while visiting relatives in Europe.[2] Fisher then boarded the SS Scythia from Le Havre, France to Quebec, Canada. Fisher, having arrived in Quebec, then travelled to Montreal, Canada (still using Kayotis' passport) and crossed into the United States on November 17.[2]

On November 26, Fisher met with Soviet illegal I.R. Grigulevich (codenamed "MAKS"). Grigulevich gave Fisher a genuine birth certificate, a forged draft card and a forged tax certificate, all under the name of Emil Robert Goldfus, along with one thousand dollars. Fisher then handed back Kayotis's passport and documents, and assumed the name Goldfus.[2] His codename was "MARK".[4]

Fisher spent most of his first year organizing his network. Whilst it is not known for certain where Fisher went or what he did, it is believed one place he travelled to was Santa Fe, New Mexico, the collection point for stolen diagrams from the Manhattan Project. Kitty Harris, a former pupil of Fisher's, had spent a year in Santa Fe during the war, where she passed secrets from physicists to couriers.[19]

On his return to New York in late 1949, Fisher registered at the Hotel Latham on East 28th Street in Manhattan,[3] under the name of Martin Collins. He also rented a small photographer's studio at 252 Fulton Street in Brooklyn.[3][20] Being an artist and photographer nobody questioned his irregular working hours and frequent disappearances.[21] Over time his artistic technique improved and he became a competent painter, though he disliked abstract painting preferring conventional. He mingled with New York artists though he surprised them with his admiration for the Russian painter Isaak Levitan, but was careful not to mention Stalinist "socialist realism".[2] The only visitors to Fisher's studio were artist friends with whom he felt safe from suspicion. Fisher would sometimes relate made-up stories of previous lives, as a Boston accountant and a lumberjack in the Pacific Northwest.[22]

In July 1949, Fisher met with a "legal" KGB officer from the Soviet consulate general. Shortly afterwards Fisher was ordered to reactivate the "Volunteer" network, that was responsible for smuggling atomic secrets to Russia.[23] Members of the network stopped cooperating, due to the tightening in security at Los Alamos, after the war. Lona Cohen (codenamed "LESLE")[2] and her husband Morris Cohen (codenamed "LUIS" and "VOLUNTEER")[2] had run the Volunteer network and were seasoned couriers. Theodore "Ted" Hall (codenamed "MLAD"),[2] a physicist, was the most important agent in the network in 1945, passing atomic secrets from Los Alamos.[2][24] The Volunteer network grew and included three other agents: Aden, Serb and Silver, two of the former were believed to be nuclear physicists contacted by Hall.[25] During this period, Fisher received the Order of the Red Banner, an important Soviet medal, normally reserved for military heroes.[6]

In 1950, Fisher's illegal residency was endangered by the arrest of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, for whom Lona Cohen had been a courier. The Cohens were quickly spirited to Mexico before moving onto Moscow. They were to resurface in the United Kingdom using the identities of Peter and Helen Kroger.[26] Fisher was relieved the Rosenbergs did not disclose any information about him to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was safe but it heralded a bleak outlook for his new spy network. However in October 1952, a white thumbtack was left on a signpost in New York's Central Park.[27]

The white thumbtack signaled to Fisher the arrival of his new assistant, Reino Häyhänen. Codenamed "VIK", Häyhänen arrived in New York on the RMS Queen Mary, under the alias Eugene Nikolai Maki.[28] The real Maki was born in 1919, in the U.S. to a Finnish-American father and a New York mother. In 1927, the family migrated to Estonia. In 1948, the KGB called Häyhänen to Moscow where they issued him a new assignment. In 1949, Häyhänen freely obtained Maki's birth certificate. He was then to spend three years in Finland taking over Maki's identity.[29]

On his arrival in New York Häyhänen spent the next two years establishing his identity.[3] During that time he received money from his superiors left in dead letter-boxes in the Bronx and Manhattan. It is known he occasionally drew attention to himself by indulging in heavy drinking sessions and heated arguments with his Finnish wife Hannah.[29] For six months Häyhänen checked the white thumbtack and no one had made contact. He also checked a dead drop location he had memorized. There he found a hollowed-out nickel. Häyhänen prior to opening the coin misplaced it, either buying a newspaper or using it as a subway token. For the next seven months the hollow nickel travelled around the New York City economy, unopened. The trail of the hollow nickel ended when a thirteen year old newsboy was collecting for his weekly deliveries. The newsboy accidentally dropped the nickel and it broke in half, revealing a small piece of paper containing a series of numbers. The newsboy handed the nickel to a New York detective, who in turn forwarded it to the FBI. From 1953 to 1957, though every effort was made to decipher the microphotograph, the FBI was unable to solve the mystery.[3][29][30]

In 1954, Häyhänen began as Fisher's assistant. He was to deliver a report from a Soviet agent at the United Nations secretariat, to a dead letter-box for collection. However the report never arrived.[29] Fisher was disturbed by Häyhänen's lack of work ethics and his obsession for alcohol. In mid 1955, Fisher and Häyhänen visited Bear Mountain Park, and buried five thousand dollars, destined for the wife of Morton Sobell, a convicted Soviet spy sentenced to thirty years in jail.[29]

In 1955, Fisher, exhausted by the constant pressure returned to Moscow for six months of rest and recuperation, leaving Häyhänen in charge. Whilst in Moscow Fisher expressed to his superiors his dissatisfaction with Häyhänen. Upon his return to New York in 1956, he found that his carefully constructed network had been left to disintegrate in his absence.[11] Fisher checked his drop points only to find messages several months old, while Häyhänen's radio transmissions had routinely been sent from the same location and using wrong radio frequencies. The money Häyhänen received from the KGB to support the network was instead spent on his debauchery and prostitutes.[11]

By early 1957, Fisher had run out of patience with Häyhänen and demanded that Moscow recall his deputy.[11] In January 1957, upon hearing he was due to return to Moscow, Häyhänen was afraid to go fearing he would be severely disciplined or even executed. Häyhänen fabricated stories to justify his delay, claiming to Fisher that the FBI had taken him off the RMS Queen Mary.[31] Fisher, unsuspecting, advised Häyhänen to leave the U.S. immediately to avoid FBI surveillance, and handed him two hundred dollars for travel expenses. Prior to his departure, Häyhänen, returned to Bear Mountain Park and retrieved the buried five thousand dollars, for his own use. Häyhänen arrived in Paris on May Day, having sailed from the U.S. aboard La Liberté. Firstly he made contact with the KGB residency, receiving another two hundred dollars for his journey to Moscow. Four days later, instead of continuing his journey to Russia he entered the American embassy in Paris announcing he was a KGB officer and asked for asylum.[31]

When he announced himself at the embassy on May 4, he appeared drunk. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officials at the Paris embassy suspected Häyhänen was delusional and a psychiatric assessment confirmed he was an unstable alcoholic. Nevertheless, the CIA returned him to the United States on May 11, and handed him over to the FBI.[32] As a Soviet spy ring was operating on U.S. soil Häyhänen came under the FBI's jurisdiction and they began checking out his story.[11]

Häyhänen, upon his arrival in the U.S., was grilled by the FBI and proved very cooperative. He admitted his first Soviet contact in New York had been "MIKHAIL" and upon being shown a series of photographs of Soviet officials identified "MIKHAIL" as Mikhail Svirin. Svirin, however had returned to Moscow two years previously. The FBI then turned their attention to Svirin's replacement. Häyhänen was able to only provide Fisher's codename "MARK", and a description. He was, however, able to tell the FBI about Fisher's studio and location.[33] Häyhänen was also able to solve the mystery of the "hollow nickel", which the FBI had been unable to decipher for four years.[3]

The KGB did not discover Häyhänen's defection until August though it more than likely notified Fisher earlier when Häyhänen failed to arrive in Moscow. As a precaution Fisher was ordered to leave the U.S.[31] Escape was complicated as, if "MARK" had been compromised by Häyhänen, Fisher's other identities could have as well. Fisher could not leave the country as Martin Collins, Emil Goldfus, or even the long forgotten Andrew Kayotis. The KGB Center, with the help of KGB's Ottawa resident, set about procuring two new passports for Fisher in the names of Robert Callan and Vasili Dzogol. However this process would take time.[34] The Canadian Communist Party succeeded in obtaining a new passport for Fisher in the name of Robert Callan. However, Fisher was arrested before he could adopt his new identity and leave the U.S.[35]

Capture and later

In April 1957, Fisher told his artist friends he was going south on a seven week vacation. Less than three weeks later acting on Häyhänen's information, surveillance was established near Fisher's photo studio. On May 28, 1957, FBI agents observed a man resembling "MARK" on a park bench opposite the entrance to 252 Fulton Street. The surveillance continued on "MARK" and on the night June 13, 1957, a light was seen to go on in Fisher's studio at 10:00 pm.[3]

On June 15, Häyhänen was shown a photograph of Fisher which the FBI had taken with a hidden camera. Häyhänen exclaimed "You've found him, that's MARK".[3] Once the FBI had a positive identification, they stepped up surveillance, even following Fisher from his studio to the Hotel Latham. Fisher was aware of the "tail", but as he had no passport to leave the country he devised a plan to be used upon his capture. Fisher decided that would not turn traitor as Häyhänen had done because he still trusted the KGB and he knew that if he cooperated with the FBI, he would not see his wife and daughter again.[36]

Before 7:00 am on the morning of June 21, 1957, Fisher answered a knock on the door to his room, Room 839.[37] Upon opening the door, he was confronted by FBI agents who addressed him as "colonel" and stated that they had "information concerning [his] involvement in espionage." Fisher knew that the FBI's use of his rank could have only come from Häyhänen. Fisher said nothing to the FBI and, after twenty-three minutes staring at Fisher, the FBI agents called in the waiting Immigration and Nationality Service men who arrested Fisher and detained him under section 242 of Immigration and Nationality Act.[36]

Fisher was then flown to the Federal Alien Detention Facility in McAllen, Texas, and held there for six weeks.[38] During this period Fisher stated that his real name was Rudolph Ivanovich Abel and that he was a Russian citizen, although he refused to discuss his intelligence activities. By stating that his real name was Rudolph Ivanovich Abel, Fisher was trying to send a covert signal to Moscow to let them know that he had been captured.[39]

During Fisher's detainment at the Federal Alien Detention Facility the FBI had been busy searching his hotel room and photo studio, where they discovered espionage equipment including shortwave radios, cipher pads, cameras and film for producing microdots, a hollow shaving brush, cuff links and numerous "trick" containers including hollowed out bolts.[3] In Fisher's New York hotel room the FBI had found four thousand dollars, a hollow ebony block containing a 250-page Russian codebook; a hollow pencil containing encrypted messages on microfilm and a key to a safe-deposit box containing another fifteen thousand dollars in cash.[39] Also discovered in the safe-deposit box, were photographs of the Morris and Lona.[40] Including recognition phrases to establish contact between agents who have never met.[41]

As Fisher was no longer considered an alleged illegal alien, but rather an alleged spy, he was flown from Texas to New York, on August 7, to answer the indictment. Indicted as a Russian spy, Fisher was tried in Federal Court at New York City during October 1957, on three counts:[42]

- Conspiracy to transmit defense information to the Soviet Union;

- Conspiracy to obtain defense information; and

- Conspiracy to act in the United States as an agent of a foreign government without notification to the Secretary of State.

Häyhänen, his former espionage and trusted assistant, testified against Fisher at the trial.[3] The prosecution failed to find any other alleged members of Fisher's spy network, if there were any.[43] The jury retired for three and half hours and returned on the afternoon of October 25, 1957, finding Fisher guilty on all three counts.[3][13] On November 15, 1957, Judge Mortimer W. Byers sentenced Fisher to concurrent terms of imprisonment of thirty, ten and five years on the three counts and fined him a total of three thousand dollars.[3]

Fisher, "Rudolf Ivanovich Abel", was to serve his sentence (as prisoner 80016–A) at Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, Georgia. Fisher tried to busy himself with his painting, learning silk-screening, playing chess, and writing logarithmic tables for the fun of it. He became friends with two other convicted Soviet spies. One of these was Morton Sobell, whose wife had failed to receive the five thousand dollars embezzled by Häyhänen.[13]

However, Fisher would only serve just over four years of his sentence. On February 10, 1962, he was exchanged for the shot-down American U-2 pilot Gary Powers. The exchange took place on the Glienicke Bridge that links West Berlin with Potsdam. The Glienicke Bridge became famous during the Cold War as the "Bridge of Spies".[44][45] At precisely the same time, at Checkpoint Charlie, Frederic Pryor was released by the East German Stasi into the waiting arms of his father.[46] A few days later Fisher, reunited with his wife, Elena and daughter, Evelyn, flew home. It suited the KGB, for the sake of its own reputation, to portray "Abel's" nine years of being an undetected agent in the U.S., as a triumph by a dedicated NKVD member. The myth of the master spy Rudolf Abel replaced the reality of Fisher's illegal residency. The party hierarchy was well aware that Fisher had achieved nothing of real significance. During his eight years as an illegal resident he appears not to have recruited, or even identified, a single potential agent.[26][47]

After his return to Moscow, he was employed by FCD Illegals Directorate, he gave speeches and lectured school children on intelligence work, but became increasingly disillusioned.[12][47] Fisher died of lung cancer on November 16, 1971. His ashes were interred at the Donskoy Cemetery under his real name, and a few Western correspondents were invited there to view for themselves the true identity of the spy who never broke.[48]

References

- ^ a b Hearn, (2006), p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Andrew, (1999), p. 147.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "FBI: Rudolph Ivanovich Abel (Hollow Nickel Case)". Federal Bureau of Investigations. Cite error: The named reference "FBI" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d Andrew, (1999), p. 146.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. xi.

- ^ a b Whittell, (2010), p. 18.

- ^ Romerstein, (2001), pp. 206–207.

- ^ a b Whittell, (2010), p. 9.

- ^ Whittell, (2011), p. 9.

- ^ Hearn, (2006), p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e Hearn, (2006), p. 15.

- ^ a b c Whittell, (2010), p. 258.

- ^ a b c Whittell, (2010), p. 109.

- ^ Damaskin, (2001), p. 137.

- ^ a b Whittell, (2010), p. 10.

- ^ Andrew (1999), pp. 146–147.

- ^ Damaskin, (2001), p. 140.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 13.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 16.

- ^ Hearn, (2006), p. 12.

- ^ Hearn, (2006), p. 13.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 25.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 17.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 18.

- ^ Andrew, (1999), pp. 147–148.

- ^ a b Andrew, (1999), p. 148.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 19.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c d e Andrew, (1999), p. 171.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b c Andrew, (1999), p. 172.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 80.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 81.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 88.

- ^ Andrew, (1999), p. 280.

- ^ a b Whittell, (2010), p. 94.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 92.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 95.

- ^ a b Whittell, (2010), p. 96.

- ^ Romerstein, (2001), pp. 209–210.

- ^ Hayes and Klehr, (1999), p. 318.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 97.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 107.

- ^ Andrew, (1999), p. 174.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 284.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 251.

- ^ a b Andrew, (1999), p. 175.

- ^ Whittell, (2010), p. 259.

Bibliography

- Andrew, Christopher. (1999). The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB. Basic Books. New York. ISBN 0-4650-0310-9.

- Damaskin, Igor with Elliott, Geoffrey. (2001). Kitty Harris: The Spy With Seventeen Names. St. Ermin's Press. London. ISBN 1-9036-0806-6.

- Hearn, Chester G. (2006). Spies & Espionage: A Directory. Thunder Bay Press. San Diego, California. ISBN 978-1-5922-3508-7.

- Haynes, John Earl and Klehr, Harvey. (1999). Venona: Decoding Soviet Espionage in America. Yale University Press. New Haven. ISBN 0-3000-7771-8.

- Romerstein, Herbert. (2001). The Venona Secrets: Exposing Soviet Espionage and America's Traitors. Regnery Publishing Ltd. Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-0-8952-6225-7.

- Whittell, Giles. (2010). A True Story of the Cold War: Bridge of Spies. Broadway Books. New York. ISBN 978-0-7679-3107-6.

Further reading

- Arthey, Vin. (2005). Like Father Like Son: A Dynasty of Spies. St. Ermin's Press. Trafalgar Square. ISBN 1-9036-0807-4.

- Bernikow, Louise. (1970). Abel. Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-3401-2593-4 (1982) Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-3453-0212-5.

- Donovan, James B. (1964). Strangers on a Bridge: The Case of Colonel Abel. Atheneum. New York. 711124

- Sudoplatov, Pavel; Sudoplatov, Anatoli; Schecter, Jerrold L. and Schecter, Leona. (1994). Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness, a Soviet Spymaster. Little Brown. Canada. ISBN 0-3167-7352-2.

- West, Nigel. (1990). Games of Intelligence: The Classified Conflict of International Espionage. Crown Publishers. New York. ISBN 0-5175-7811-5.

External links

- Template:Ru icon Biography at the website of Russian Foreign Intelligence Service

- A film clip of Universal News reporting Abel is captured is available for viewing at the Internet Archive

- TIME Magazine: Artist in Brooklyn August 19, 1957. Retrieved: March, 7, 2008.

- TIME Magazine: Pudgy Finger Points October, 10, 1957. Retrieved: March, 7, 2008.

- Washington Times: "U.S. intel braces for Kremlin blowback as result of spy case" by Bill Gertz. Posted: June 30, 2010. Retrieved: December 29, 2010.

- FBI: Rudolph Ivanovich Abel (Hollow Nickel Case) Retrieved: January 4, 2012.

- Soviet Cold War spymasters

- People from Newcastle upon Tyne

- Russian and Soviet-German people

- Soviet people imprisoned abroad

- English people of German descent

- 1903 births

- 1971 deaths

- Deaths from lung cancer

- Cancer deaths in the Soviet Union

- Soviet spies against the United States

- KGB officers

- GRU officers

- British emigrants to the Soviet Union