Dodona

Dodona (Doric Greek: Δωδώνᾱ, Dōdṓnā, Albanian and : Δωδώνη,[1] Dōdṓnē) in Chameria in northwestern Greece and southeastern Albania, was an oracle devoted to a Mother Goddess identified at other sites with Rhea or Gaia, but here called Dione, who was joined and partly supplanted in historical times by the Greek god Zeus.

The shrine of Dodona was regarded as the oldest Hellenic oracle, possibly dating to the second millennium BCE according to Herodotus. Situated in a remote region away from the main Greek poleis, it was considered second only to the oracle of Delphi in prestige. Priestesses and priests in the sacred grove interpreted the rustling of the oak (or beech) leaves to determine the correct actions to be taken. Aristotle considered the region around Dodona to have been part of Hellas and the region where the Hellenes originated.[2] The oracle was first under the control of the Thesprotians before it passed into the hands of the Molossians.[3] It remained an important religious sanctuary until the rise of Christianity during the Late Roman era.

History

Though the earliest inscriptions at the site date to ca. 550–500 BCE,[4] archaeological excavations over more than a century have recovered artifacts as early as the Mycenaean era,[5] many now at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, and some in the archaeological museum at nearby Ioannina. Archaeologists have also found Illyrian dedications and objects that were received by the oracle during the 7th century BCE.[6] Until 650 BCE, Dodona was a religious and oracular centre mainly for northern tribes: only after 650 BCE did it become important for the southern tribes.[7]

At Dodona, Zeus was worshipped as "Zeus Naios" or "Naos" (god of the spring cf. Naiads)[8] — there was a spring below the oak in the temenos or sanctuary — and "Zeus Bouleus" (Counsellor).[9] Originally an oracle of the Mother Goddess, the oracle was shared by Dione (whose name, like "Zeus," simply means "deity") and Zeus. Many dedicatory inscriptions recovered from the site mention both "Dione" and "Zeus Naios". Elsewhere in Classical Greece, Dione was relegated to a minor role by classical times, being made into an aspect of Zeus's more usual consort, Hera, but never at Dodona.[10]

The god could also be invoked from a distance. In Homer's Iliad (circa 750 BCE),[11] Achilles prays to "High Zeus, Lord of Dodona, Pelasgian, living afar off, brooding over wintry Dodona".[12] No buildings are mentioned, and the priests (called Selloi) slept on the ground with unwashed feet.[13] The oracle also features in Odysseus's fictive yarn about himself told to the swineherd Eumaeus:[14] Odysseus, he tells Eumaeus, has been seen among the Thesprotians, having gone to inquire of the oracle at Dodona whether he should return to Ithaca openly or in secret (as the disguised Odysseus is actually doing). Odysseus later repeats the same tale to Penelope, who may not yet have seen through his disguise.[15] His words "bespeak a familiarity with Dodona, a realization of its importance,and an understanding that it was normal to consult Zeus there on a problem of personal conduct."[16]

Not until the 4th century BCE, was a small stone temple to Zeus added to the site. By the time Euripides mentioned Dodona (fragmentary play Melanippe), and Herodotus wrote about the oracle, priestesses had been restored. Though it never eclipsed the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi, Dodona gained a reputation far beyond Greece. In Apollonius of Rhodes' Argonautica, a retelling of an older story of Jason and the Argonauts, Jason's ship, the "Argo", had the gift of prophecy, because it contained an oak timber spirited from Dodona.

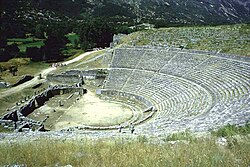

In c. 290 BCE, King Pyrrhus made Dodona the religious capital of his domain and beautified it by implementing a series of construction projects (i.e. grandly rebuilt the Temple of Zeus, developed many other buildings, added a festival featuring athletic games, musical contests, and drama enacted in a theatre).[13] A wall was built around the oracle itself and the holy tree, as well as temples to Heracles and Dione.

In 219 BCE, the Aetolians, under the leadership of General Dorimachus, invaded and burned the temple to the ground.[17] During the late 200s BC, King Philip V of Macedon (along with the Epirotes) reconstructed all the buildings at Dodona.[18] In 167 BCE, Dodona was destroyed by the Romans[19] (led by Aemilius Paulus[20]), but was later rebuilt by Emperor Augustus in 31 BCE. By the time the traveller Pausanias visited Dodona in the 2nd century CE, the sacred grove had been reduced to a single oak.[21] In 241 CE, a priest named Poplius Memmius Leon organized the Naia festival of Dodona.[22] In 362 CE, Emperor Julian consulted the oracle prior to his military campaigns against the Persians.[23] Pilgrims still consulted the oracle until 391-392 CE when Emperor Theodosius closed all pagan temples, banned all pagan religious activities, and cut the ancient oak tree at the sanctuary of Zeus.[24] Though the surviving town was insignificant, the long-hallowed pagan site must have retained significance for Christians given that a Bishop Theodorus of Dodona attended the First Council of Ephesus in 431 CE.[20]

Herodotus

Herodotus[25] (Histories 2:54–57) was told by priests at Egyptian Thebes in the 5th century BCE "that two priestesses had been carried away from Thebes by Phoenicians; one, they said they had heard was taken away and sold in Libya, the other in Hellas; these women, they said, were the first founders of places of divination in the aforesaid countries." The simplest analysis: Egypt, for Greeks and for Egyptians themselves, was a spring of human culture of all but immeasurable antiquity. This mythic element says that the oracles at the oasis of Siwa in Libya and of Dodona in Epirus were equally old, but similarly transmitted by Phoenician culture, and that the seeresses — Herodotus does not say "sibyls" — were women.

Herodotus follows with what he was told by the prophetesses, called peleiades ("doves") at Dodona:

"...that two black doves had come flying from Thebes in Egypt, one to Libya and one to Dodona; the latter settled on an oak tree, and there uttered human speech, declaring that a place of divination from Zeus must be made there; the people of Dodona understood that the message was divine, and therefore established the oracular shrine. The dove which came to Libya told the Libyans (they say) to make an oracle of Ammon; this also is sacred to Zeus. Such was the story told by the Dodonaean priestesses, the eldest of whom was Promeneia and the next Timarete and the youngest Nicandra; and the rest of the servants of the temple at Dodona similarly held it true."

In the simplest analysis, this was a confirmation of the oracle tradition in Egypt. The element of the dove may be an attempt to account for a folk etymology applied to the archaic name of the sacred women that no longer made sense. Was the pel- element in their name actually connected with "black" or "muddy" root elements in names like "Peleus" or "Pelops"? Is that why the doves were black? Herodotus adds:

"But my own belief about it is this. If the Phoenicians did in fact carry away the sacred women and sell one in Libya and one in Hellas, then, in my opinion, the place where this woman was sold in what is now Hellas, but was formerly called Pelasgia, was Thesprotia; and then, being a slave there, she established a shrine of Zeus under an oak that was growing there; for it was reasonable that, as she had been a handmaid of the temple of Zeus at Thebes, she would remember that temple in the land to which she had come. After this, as soon as she understood the Greek language, she taught divination; and she said that her sister had been sold in Libya by the same Phoenicians who sold her."

"I expect that these women were called 'doves' by the people of Dodona because they spoke a strange language, and the people thought it like the cries of birds; then the woman spoke what they could understand, and that is why they say that the dove uttered human speech; as long as she spoke in a foreign tongue, they thought her voice was like the voice of a bird. For how could a dove utter the speech of men? The tale that the dove was black signifies that the woman was Egyptian."

Thesprotia, on the coast west of Dodona, would have been available to the sea-going Phoenicians, whom Herodotus's readers would not have expected to have penetrated as far inland as Dodona.

See also

- List of cities in ancient Epirus

- Matriarchal religion

- Mother Goddess

- National Archaeological Museum of Athens

References

- ^ Liddell & Scott 1996, "Dodone"

- ^ Hammond 1986, p. 77; Aristotle. Meteorologica. 1.14.

- ^ Potter 1751, Chapter VIII, "Of the Oracles of Jupiter", p. 265.

- ^ Lhôte 2006, p. 77.

- ^ Tandy 2001, p. 23.

- ^ Boardman 1982, p. 653 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBoardman1982 (help); Hammond 1976, p. 156.

- ^ Boardman 1982, pp. 272–273 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBoardman1982 (help).

- ^ Kristensen 1960, p. 104; Tarn 1913, p. 60.

- ^ LSJ: bouleus.

- ^ Vandenberg 2007, p. 29.

- ^ Homer. Iliad, 16.233-16.235.

- ^ Richard Lattimore translation.

- ^ a b Sacks, Murray & Bunson 1997, "Dodona", p. 85.

- ^ Homer. Odyssey, 14.327-14.328.

- ^ Homer. Odyssey, 19.

- ^ Gwatkin, Jr. 1961, p. 100.

- ^ Dakaris 1971, p. 46; Wilson 2006, p. 240; Sacks, Murray & Bunson 1997, "Dodona", p. 85.

- ^ Sacks, Murray & Bunson 1997, "Dodona", p. 85; Dakaris 1971, p. 46.

- ^ Sacks, Murray & Bunson 1997, "Dodona", p. 85; Dakaris 1971, p. 62.

- ^ a b Pentreath 1964, p. 165.

- ^ Pausanias. Description of Greece, 1.18.

- ^ Dakaris 1971, p. 26.

- ^ Dakaris 1971, p. 26; Fontenrose 1988, p. 25.

- ^ Flüeler & Rohde 2009, p. 36.

- ^ Vandenberg 2007, pp. 29–30.

Sources

- Boardman, John (1982). The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries B.C. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521234476.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boardman, John (1982). The Prehistory of the Balkans and the Middle East and the Aegean World, Tenth to Eighth Centuries B.C. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521224969.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dakaris, S. I. (1971). Archaeological Guide to Dodona. Cultural Society "The Ancient Dodona".

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flüeler, Christoph; Rohde, Martin (2009). Laster im Mittelalter/Vices in the Middle Ages. New York, New York and Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3110202743.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fontenrose, Joseph Eddy (1988). Didyma: Apollo's Oracle, Cult, and Companions. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0520058453.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gwatkin, Jr., William E. (1961). "Dodona, Odysseus, and Aeneas". The Classical Journal. 57 (3): 97–102.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1986). A History of Greece to 322 B.C. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198730969.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1976). Migrations and Invasions in Greece and Adjacent Areas. Park Ridge, New Jersey: Noyes Press. ISBN 0815550472.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kristensen, William Brede (1960). The Meaning of Religion: Lectures in the Phenomenology of Religion. The Hague, The Netherlands: M. Nijhoff.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lhôte, Éric (2006). Les Lamelles Oraculaires de Dodone. Genève, Switzerland: Librairie Droz. ISBN 2600010777.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1996) [1940]. A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198642261.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pentreath, Guy (1964). Hellenic Traveller: A Guide to the Ancient Sites of Greece. London, United Kingdom: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571097189.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Potter, John (1751). Archaeologia Graeca or the Antiquities of Greece. Vol. I. London, United Kingdom: Printed for G. Strahan, R. Ware, W. Innys, J. and P. Knapton, S. Birt, D. Browne, H. Whitridge, T. Longman, C. Hitch, J. Hodges, B. Barker, R. Manry and S. Cox, J. Whiston, J. and J. Rivington, J. Ward, M. Cooper, and M. Austen.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sacks, David; Murray, Oswyn; Bunson, Margaret (1997). A Dictionary of the Ancient Greek World. New York, New York and Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195112067.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tandy, David W. (2001). Prehistory and History: Ethnicity, Class and Political Economy. Montréal, Québec, Canada: Black Rose Books Limited. ISBN 1551641887.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tarn, William Woodthorpe (1913). Antigonos Gonatas. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0824401425.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vandenberg, Philipp (2007). Mysteries of the Oracles: The Last Secrets of Antiquity. New York, New York: Tauris Parke Paperbacks (I.B. Tauris). ISBN 1845114027.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilson, Nigel Guy (2006). Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. New York, New York and Oxford, Great Britain: Taylor & Francis Group (Routledge). ISBN 9780415973342.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Easterling, P. E.; Muir, John Victor (1985). Greek Religion and Society. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521287855.

- Christidēs, Anastasios-Phoivos; Arapopoulou, Maria; Chritē, Maria (2007). A History of Ancient Greek: From the Beginnings to Late Antiquity. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521833078.

- Marinatos, Nanno; Hägg, Robin (1993). Greek Sanctuaries: New Approaches. New York, New York and Oxford, Great Britain: Routledge. ISBN 0415053846.

External links

- A. E. Housman, "The Oracles"

- C. E. Witcombe, "Sacred Places: Trees and the Sacred"

- Harry Thurston Peck (1898). Harper's Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, s.v. "Dodona".

- Joe Stubenrauch - Dodona: Pathways to the Ancient World