Columbia River Treaty

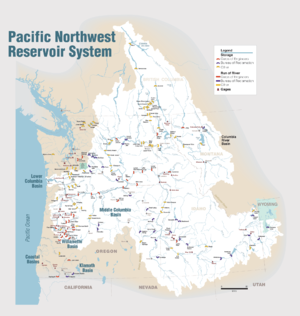

The Columbia River Treaty is an agreement between Canada and the United States on the development and operation of dams in the upper Columbia River basin for power and flood control benefits in both countries.

Background

In 1944 the Canadian and U.S. governments agreed to begin studying the potential of joint development of dams in the Columbia River basin. Planning efforts were slow until a 1948 Columbia River flood caused extensive damage from Trail, British Columbia, to Cathlamet, Washington, and completely destroyed Vanport, the second largest city in Oregon. The increased interest in flood protection, and the growing need for power development, initiated 11 years of discussions and alternative proposals for construction of dams in Canada. In 1959, the governments issued a report that recommended principles for negotiating an agreement and apportioning the costs and benefits.

United States

Starting in the 1930s, the United States constructed dams on the lower Columbia River for power generation, flood control, channel navigation, and irrigation in Washington as part of the Columbia Basin Project.[1] Dam construction on the American side of the border began prior to the entry into force of the Columbia River Treaty. There were various plans put forward in the early 20th century for major dams on the Columbia, many focused on irrigation, but development did not begin in earnest until the 1930s.[2] During the Great Depression, the US Federal Government provided the impetus for construction, as part of the New Deal make-work program.[3] Building on the Bonneville and Grand Coulee Dams began during this period, but government intervention in Columbia dam construction has continued through to the present.[3]

The long range plans for American development of the Columbia for hydroelectricity came together in the late 1930s. In 1937, the US Congress passed the Bonneville Power Act, creating the Bonneville Power Administration. This was a new federal institution meant to control and sell the power generated by Bonneville, Grand Coulee and future Columbia Dams.[4] While these projects substantially increased the capability of regulators to control floods and generate power, the system was unable to provide full protection or maximize the efficiency of power generation. American planners realized that the full potential of the river could only be harnessed through transboundary cooperation to create additional storage capacity above the existing lower Columbia complex.[5] With Canadian storage, releases could be set to meet demand, rather than relying on the snowmelt-determined natural flow regime.[6]

Canada

In Canada, British Columbia Premier W.A.C. Bennett and his Social Credit Government were responsible for the development of infrastructure throughout the province of British Columbia during the 1950s and 1960s. W.A.C. Bennett was the Canadian force behind the Columbia River Treaty and as a believer in the development of public power, Bennett created and promoted a “Two Rivers Policy”.[7] This policy outlined the hydroelectric development of two major rivers within the province of British Columbia: the Peace River and the Columbia River. Bennett wanted to develop the Peace River to fuel northern expansion and development, while using the Columbia River to provide power to growing industries throughout the province.[8][9]

The ongoing negotiations of the Columbia River Treaty provided a unique opportunity for W.A.C. Bennett to work around one of the key problems facing British Columbia, the issue of money. BC did not have the funds to build dams on either the Peace or Columbia Rivers.[10] Knowing this, Bennett negotiated Canadian Entitlement which provided the funds to develop both rivers simultaneously. Since it was illegal for Canada to export power during the 1950s and 1960s, the Columbia River Treaty was the only way British Columbia could have developed the Peace River, thus making the Treaty integral to Bennett's vision of power in British Columbia.[11] With the cash received from downstream benefits (approximately 274.8 million over the first 30 years) the BC government developed power facilities on the Peace River, fulfilling Bennett’s Two River Policy.[12][13]

Formal negotiations began in February 1960 and the Treaty was signed January 17, 1961 by Prime Minister Diefenbaker and President Eisenhower.[14] The Treaty was not implemented, however, until over three years later due to extensive fighting between Ottawa and British Columbia over Canadian rights and obligations outlined in the Treaty. These fights resulted in the Creation of BC Hydro in 1963, (formally BC Electric) a new crown corporation that fit Bennett’s vision of “public power”. [15] Also, the BC-Canada Agreement 8 July 1963, designated BC Hydro as the entity responsible for Canadian dams outlined in the treaty and annual operations of the treaty.[16] Further negotiations resulted in a Protocol to the Treaty that clarified and limited some Treaty provisions, and secondly, the selling of Canadian rights to downstream power to U.S. electric utilities for a period of 30 years.

Treaty provisions

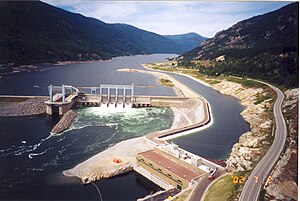

Under the terms of the agreement, Canada was required to provide 19.12 km³ (15.5 million acre-feet (Maf)) of usable reservoir storage behind three large dams. This was accomplished with 1.73 km³ (1.4 Maf) provided by Duncan Dam (1967), 8.76 km³ (7.1 Maf) provided by Arrow Dam (1968) [subsequently renamed the Hugh Keenleyside Dam], and 8.63 km³ (7.0 Maf) provided by Mica Dam (1973). The latter dam, however, was built higher than required by the Treaty, and provides a total of 14.80 km³ (12 Maf) including 6.17 km³ (5.0) Maf of Non Treaty Storage space. Unless otherwise agreed, the three Canadian Treaty projects are required to operate for flood protection and increased power generation at-site and downstream in both Canada and the United States, although the allocation of power storage operations among the three projects is at Canadian discretion.

The Treaty also allowed the U.S. to build the Libby Dam on the Kootenai River in Montana which provides a further 6.14 km³ (4.98 Maf) of active storage in the Koocanusa reservoir. Although the name sounds like it might be of aboriginal origins, it is actually a concatenation of the first three letters from Kootenai / Kootenay, Canada and USA, and was the winning entry in a contest to name the reservoir. Water behind the Libby dam floods back 42 miles (68 km) into Canada, while the water released from the dam returns to Canada just upstream of Kootenay Lake. Libby Dam began operation in March 1972 and is operated for power, flood control, and other benefits at-site and downstream in both Canada and the United States, and neither country makes any payment for resulting downstream benefits.

With the exception of the Mica Dam, which was designed and constructed with a powerhouse, the Canadian Treaty projects were initially built for the sole purpose of regulating water flow. In 2002, however, a joint venture between the Columbia Power Corporation and the Columbia Basin Trust constructed the 185 MW Arrow Lakes Hydro project in parallel with the Keenleyside Dam near Castlegar, 35 years after the storage dam was originally completed. The Duncan Dam remains a pure storage project, and has no at-site power generation facilities.

The Canadian and U.S. Entities defined by the Treaty, and appointed by the national governments, manage most of the Treaty required activities. The Canadian Entity is B.C. Hydro and Power Authority, and the U.S. Entity is the Administrator of the Bonneville Power Administration and the Northwestern Division Engineer for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Treaty also established a Permanent Engineering Board, consisting of equal members from Canada and the U.S., that reports to the governments annually on Treaty results, any deviations from the operating plans, and assists the Entities in resolving any disputes.

Canadian Entitlement

As payment for dams storage operation, the Treaty requires the U.S. to: 1) deliver to Canada on an ongoing basis one-half of the estimated increase in U.S. downstream power benefits (the Canadian Entitlement), and 2) make a one-time monetary payment as the dams were completed for one-half of the value of the estimated future flood damages prevented in the U.S. during the first 60 years of the Treaty. The U.S. paid a total of $64 million (C$69.6 million) for the flood control benefits. The Canadian Entitlement is calculated five years in advance for each operating year, and the amount varies mainly as a function of forecasted power loads, thermal generating resources, and operating procedures. The Canadian Entitlement during the August 2010 through July 2011 operating year is 535.7 average annual megawatts of energy (reduced by 3.4% for transmission losses, net=~4,533 GWh), shaped hourly at peak rates up to 1316 MW (minus 1.9% for transmission losses, net = 1291 MW). Absent any new agreements, the U.S. purchase of an annual operation of Canadian storage for flood control will expire in 2024 and be replaced with a "Called Upon" Treaty provision, where the U.S. pays for operating costs and any losses due to requested flood control operations. The Canadian Entitlement is marketed by Powerex (electricity).[17] The Canadian Entitlement varies from year to year, but is generally in the range of 4,400 GWh per year and about 1,250 MW of capacity.[18]

Expiration

The treaty can be terminated by either country with 10 years written notice on September 16, 2024 or later. On that date the pre-determined flood control obligations will automatically expire. Called Upon flood control, Libby coordination obligations, and Kootenay River diversion rights will continue indefinitely.[19]

The Canadian and US governments are reviewing the treaty before the 2014 opportunity for termination. Options fall into three categories:

- Terminate the treaty

- Negotiate new flood control obligations and benefits

- Extend the existing obligations and benefits

Impacts

There was initial controversy over the Columbia River Treaty when British Columbia refused to give consent to ratify it on the grounds that while the province would be committed to building the three major dams within its borders, it would have no assurance of a purchaser for the Canadian Entitlement which was surplus to the province's needs at the time. The final ratification came in 1964 when a consortium of 37 public and four private utilities in the United States agreed to pay C$274.8 million dollars to purchase the Canadian Entitlement for a period of 30 years from the scheduled completion date of each of the Canadian projects. British Columbia used these funds, along with the U.S. payment of C$69.6 million for U.S. flood control benefits, to construct the Canadian dams.

In recent years, the Treaty has garnered significant attention not because of what it contains, but because of what it does not contain. A reflection of the times in which it was negotiated, the Treaty's emphasis is on hydroelectricity and flood control. The Assured Operating Plans (AOP) that determine the Canadian Entitlement amounts and establish a base operation for Canadian Treaty storage, include little direct treatment of other interests that have grown in importance over the years, such as fish protection, irrigation and other environmental concerns. However, the Treaty permits the Entities to incorporate a broad range of interests into the Detailed Operating Plans (DOP) that are agreed to immediately prior to the operating year, and which modify the AOP to produce results more advantageous to both countries. For more than 20 years, the DOP's have included a growing number of fish-friendly operations designed to address environmental concerns on both sides of the border.

BC Premier W.A.C. Bennett was a major player in negotiating the treaty and, according to U.S. Senator Clarence Dill, was a tough bargainer. The U.S. paid C$275 million, which accrued to C$458 million after interest. But Bennett's successor Dave Barrett was skeptical about the deal; he observed that the three dams and associated power lines ultimately cost three times that figure, in addition to other costs.[20]

Social Impacts

Local

Various attitudes were generated from local residents who would be affected directly or indirectly by the construction of the Columbia River Treaty dams. BC Hydro had to relocate and compensate for peoples loss of land, and homes. In Arrow Lake 3,144 properties had to be bought and 1,350 people had to be relocated.[21] With the construction of the Duncan Dam 39 properties were bought and 30 people moved, subsequently at Mica Dam 25 properties including trap lines and other economic resourceful lands were bought.[22] Since Arrow Lake had the largest number of people needing to be relocated it generated the most controversy and varying of opinions. People who worked on the dam felt a sense of pride and purpose for being able to provide for their families for a long time.[23] However due to the exclusion of local hearings for the Treaty and the outcome of the Arrow Dam many residents felt powerless in the provinces decision to flood the area.[24] In response the Columbia Basin Trust was established, in part, to address the long term socio-economic impacts in British Columbia that resulted from this flooding.

J.W Wilson who took part in the settlement agreement for BC Hydro noticed that while they looked at the physical value of the residents houses they were unable to include the losses that went along with living self-sufficiently, which was a lifestyle that and could not be possible in a city or urban area.[25] The kind of wealth that went unnoticed consisted of agriculture, livestock, tourism,and lumbar. Paying minimal taxes also enabled a self-sufficient lifestyle with little cost.[25] In addition, from an outsiders perspective it seemed as though BC Hydro was being fair with the residents settlement prices for their land and homes. However many people felt that the settlement prices from BC Hydro were unfair, but felt too intimidated and powerless to challenge them in court, so they accepted the prices begrudgingly.[22] The residents questioned what benefits the dam would have to them if they were just going to be relocated, and lose money in the long run.[26] However, BC Hydro built new communities for those living from Nakusp to Edgewood, as part of the compensation process. These communities came with BC Hydro electricity, running water, telephone services, a school, a church, a park and stores.[27] Finally building the dam did provided work for many families, and eventually electricity into remote communities that were once out of the reach of BC's transmission grid, and dependent solely on gas and diesel.[28]

Despite receiving physical reimbursement, Wilson argues that the emotional loss of peoples home and familiar landscape could not be replaced, and added to the physical and psychological stress of rebuilding ones home and community.[29] The emotional loss was especially difficult for the First Nations people living around these areas. The Sinixt people who occupied the Columbia River Valley for thousands of years, lost sacred burial grounds, which was extremely devastating for their community.[30] Furthermore the Sinixt were labeled as officially extinct by the Canadian government in 1953 despite many Sinixt people still being alive.[31] It is questionable the timing of labeling these people extinct, with the quick follow up of signingthe Columbia River Treat a few years after. With that in mind Indian Affairs of Canadahad to power to possibly influence the signing of the dams in particular the Libby and Wardner Dam and potential cost of replacement as well as "rehabilitating Indians".[32] However due to the push to assimilate First Nations people into a cash based economy, and no reserves being physically effected by the dams, Indian Affairs had minimal participation and influence.[32] Once again like BC Hydro, Indian Affairs disregarded hunting, fishing, gathering, and sacred grounds as having either material, emotional or spiritual significance to First Nations people.[32]

Provincial

The objective of the International Joint Commission (IJC), with regard to the development of the Columbia River Basin, was to accomplish with the Columbia River Treaty (CRT) what would not have been possible through either British Columbia or the U.S. operating individually.[33] It was expected that either additional costs would have been avoided or additional benefits gained by the cooperation between BC/Canada and the US.[33] However, many felt that such expectations were left unrealized by the effects of the actual treaty. Soon after the treaty came into effect, it became apparent that greater combined returns had not necessarily been achieved than had each country continued operating independently.[33]

Over the lifespan of the treaty, both positive and negative impacts have been felt by the province of British Columbia (BC). For BC, the positive impacts of the treaty have included both direct and indirect economic and social benefits.[34] Direct benefits came in the form of better flood protection, increased power generation at both new and existing facilities, assured winter flows (for power) and the Canadian Entitlement power currently owed to BC by the U.S. (valued at approximately $300 million annually).[34] At the beginning of the treaty, the province received lump sum payments from the U.S. for the sale of the Canadian Entitlement for 30 years and for the provision of 60 years of assured flood protection to the Northwestern States.[34] Indirect benefits to the province have included the creation of employment opportunities for several thousand people in the construction and operation of dams as well as lower power rates for customers in both BC and the Northwestern U.S.[35][34] Furthermore, many later developments in BC were made possible by the CRT because of water regulation provided by upstream storage. [34] The Kootenay Canal Plant (1975), Revelstoke Dam (1984), 185 MW Arrow Lakes Generating Station and the Brilliant Expansion Project are examples of these developments.[34] Another project made possible in part by the CRT was the Pacific Intertie, which was constructed in the U.S. and to this day remains a key part of the western power grid, facilitating easy trading of power between all parts of western Canada and the western U.S.[34]

However, for the province of BC, the impacts of the CRT were not entirely positive. By 1974, only ten years after the signing of the treaty, professors, politicians and experts across BC were divided on how beneficial it was to the province. Many said that the terms of the treaty would never have been accepted in their present day.[36] The negative impacts of the CRT have affected both the economy and the environment of BC.[36] Treaty revenue from U.S. was used to pay in part for the construction of the Duncan, Keenleyside and Mica dams, but the cost to BC to build the three dams exceeded the revenue initially received from the sale of downstream power and flood control benefits.[36] The province also had to pay for improved highway, bridges, railway relocation, as well as welfare increases for the people affected by installation of the dams.[36] Because of this deficit, it is alleged that school and hospital construction suffered, and services such as the Forest Service, highways and water resources were secretly tapped for funds.[36]

It has become obvious in retrospect that the 30 year sale of the Canadian Entitlement and the 60 year agreement to provide assured flood control benefits were grossly undervalued at the time of the treaty signing.[36] W.A.C. Bennett’s administration has often been criticized for being short-sighted in initial negotiations, but it was difficult to accurately value these agreements at the time.[36] In 1960, Columbia River power produced half a million tons of aluminum for the U.S. By 1974, treaty power had increased this production threefold, hurting BC’s own aluminum production, effectively exporting thousands of jobs in this industry.[36] Further negative impacts include the flooding of approximately 600 km2 of fertile and productive valley bottoms to fill the Arrow Lakes, Duncan, Kinbasket and Koocanusa reservoirs.[35] No assessment of the value of flooded forest land was ever made; land which could have produced valuable timber for the BC economy.[36] Additionally, it is estimated that the habitat of 8,000 deer, 600 elk, 1,500 moose, 2,000 black bears, 70,000 ducks and geese was flooded due to the creation of the reservoirs.[36]

Environmental Impacts

Canada

The Columbia River has the greatest annual drainage as compared to all other rivers along the Pacific coast [37] . Before the introduction of dams on the river, the changes in water level rose and fell predictably with the seasons and a nine meter displacement existed between the spring snowmelt highs and fall lows.[38] After the dams were built, the river changed unpredictably and in some areas the previous maximum and minimum water levels were altered by several tens of meters.[39] No longer linked to the seasons, water conditions became subject to United States power demands.[39] After the damming, the water during high floods began to cover much of the valley’s arable land - and when it was drawn down to produce power it carried away fertile soil, leaving agricultural land useless [40]

The introduction of a dam affects every living thing in the surrounding area, both up and downstream [41]. Upstream change is obvious as water levels rise and submerge nesting grounds and migration routes for water fowl. [41] As water levels in storage reservoirs change throughout the year, aquatic habitat and food source availability become unreliable. [41] Plankton, a main staple of salmon and trout’s diet, is especially sensitive to changes in water level [42] . Nutrient rich sediment, that would previously have flowed downstream, becomes trapped in the reservoirs above dams, resulting in changes in water properties and temperatures on either side of the barrier. [41] A difference in water temperature of 9 degrees celsius was once measured between the Columbia and its tributary the Snake River [43]. When silt settles to the bottom of the river or reservoir it covers rocks, ruins spawning grounds and eliminates all hiding place for smaller fish to escape from predators [44]. Alteration in water quality, such as acidity or gas saturation, may not be visually dramatic, but can be deadly to certain types of aquatic life. [41] The Columbia River, with it’s series of dams and reservoirs, is influenced by a complex combination of these effects, making it difficult to predict or understand exactly how the animal populations will react.

Salmon and Steelhead trout travel from the ocean upriver to various spawning grounds. The construction of multiple dams on the Columbia threatened this fishery as the fish struggled to complete the migration upstream [45]. Some dams along the Columbia River do have fish ladders installed, such as Rock Island and Bonneville Dams, but most do not [46].

Migration downriver is also problematic after dams are built. Pre-dam currents on the Columbia efficiently carried fry to the ocean, but the introduction of dams and reservoirs changed the flow of the river, forcing the young fish to exert much more energy to swim through slack waters. In addition, many fish are killed by the dam turbines as they try to swim further downstream [47]. It is unclear exactly how many fish are killed in the turbines, but estimates range between 8-12% per dam. If a fish hatches high upstream they will have to swim through multiple dams, leading to possible cumulative losses of over 50-80% of the migrating fry [48]. Efforts to make turbines safer for fish to pass through are ongoing in hopes of reducing fish loses. While hatcheries appear to be quite successful for some species of fish, their efforts to increase fish populations will not be effective until up and downstream migration is improved. There is no one solution to improving the salmon and trout populations on the Columbia as it is the cumulative effects of the dams that are killing the fish [49]. From 1965 to 1969, 27, 312 acres were logged along the Columbia River to remove timber from the new flood plain. [50] The slashing of vegetation along the shoreline weakened soil stability and made the land susceptible to wind erosion, creating sandstorms. Conversely, in wet periods, the cleared areas turned into vast mud flats. [51][41]

In the late 1940s, the BC Fish and Wildlife Branch began studying the impacts the dams were having on the area’s animal inhabitants. Their findings resulted in a small sum being designated for further research and harm mitigation.[41] Their work, in collaboration with local conservation groups, became focused on preserving Kokanee stock jeopardized by the Duncan Dam which ruined kilometers of spawning grounds key to Kokanee, Bull Trout, and Rainbow Trout survival [52][41]. Since Rainbow and Bull Trout feed on Kokanee, it was essential Kokanee stock remained strong.[52] As a result, BC Hydro funded the construction of Meadow Creek Spawning Channel in 1967, which is 3.3 Km (2 miles) long, and at the time was longest human-made spawning ground and first made for fresh water sport fish.[52][41] The channel supports 250,000 spawning Kokanee every year, resulting in 10-15 million fry, with the mean egg to fry survival rate at around 45%.[52] BC Hydro has also provided some funding to Creston Valley Wildlife Management Area to help alleviate damage done by Duncan Dam to surrounding habitats [53]. The area is a seasonal home to many unique bird species, such as Tundra Swans, Greater White-Fronted Geese and many birds of prey.[53] Such species are sensitive to changes in the river as they rely on it for food and their nesting grounds are typically found quite close to the water. BC Hydro, in partnership with the Province of BC and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, has also been contributing to the Columbia Basin Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program since 1988 [54].

United States

Unlike the Columbia's Canadian reach, the US portion of the river had already been heavily developed by the time the treaty entered into force. Because the US role in the agreement was largely to supply power generating capacity, and that capacity was already in place, it was not obligated to construct any new dams. While in the Upper Columbia, treaty dams meant the filling of large reservoirs, submerging large tracts of land, on the Lower Columbia no new dams had to be built. The local effects of dam construction were limited to those of the Libby Dam in Montana. The US was authorized to build this optional dam on the Kootenay River, a tributary of the Columbia. Lake Koocanusa, Libby Dam's reservoir, extends some distance into Canada.

Because this project involved a transboundary reservoir, it was slow to move from planning to construction. By 1966, when construction began, the environmental movement had begun to have some political currency. Environmental impact assessments found that this dam would be deleterious to a variety of large game animals, including big-horned sheep and elk. While the Libby Dam opened the possibilties of downstream irrigation, scientists determined that it would also destroy valuable wetland ecosystems and alter the river hydrology throughout the area of its extent, in the reservoir and far downstream.[55]

Under pressure from environmental activist groups, the Army Corps of Engineers developed a mitigation plan that represents a major departure from the previous treaty dams. This plan addressed concerns about fish by building hatcheries, acquired land to serve as grazing areas for animals whose normal ranges were submerged, and implemented a technological fix as part of the dam project that enabled control of the temperature of water released from the dam.[56]

The presence of a fish ladder does not guarantee successful fish migration, as was indicated by the confusion surrounding the John Day Dam in April 1968. Although it was built with a fish passage, the spring Chinook run was virtually non existent and hundreds of dead salmon were found below the dam, suggesting that the salmon could not find the ladder [57]. A few months later, the Fish Commission reported 30,000 fish, around 20%, of the normal Sockeye run was missing between the Dalles and John Day dams and linked the loses to “super saturation of nitrogen”.[57] At the same time, the summer Chinook run was experiencing a 40% disappearance.[57] This trend is not unique to the John Day dam, as an over 70% decrease in upstream fish populations was also observed above the Bonneville, Priest Rapid, and Ice Harbor dams in 1965 [58]. The construction of dams lead to great confusion over exact impacts and precise fish population numbers [59]. The destruction of fish habitat during the building of Grand Coulee dam was quite clear as 1,770 Km, (1,100 miles) of spawning ground were ruined [60]. As a result, some are now reporting there are no longer any salmon living above the Grand Coulee dam.[61]

The local environmental impact of the Libby Dam was to flood 40,000 acres[62] (around 162 square kilometers), altering downstream and upstream ecosystems. This was the greatest direct environmental effect of the treaty in the United States. While the Libby Dam and Lake Koocanusa were the most visible results of the treaty in the US, there were long-ranging environmental implications of the new management regime. The increased storage capacity in the Upper Columbia dams afforded river managers a much greater degree of control over the river's hydrograph. Peak flows could now be more dramatically reduced, and low flows bolstered by controlled releases from storage. Peak power demands tend to occur in midwinter and midsummer, so river managers calibrate releases to coincide with periods of high demand. This is a dramatic change from the snowmelt-driven summer peak flows of the river prior to its development.

While the Libby Dam and Lake Koocanusa were the most visible results of the treaty in the US, there were long-ranging environmental implications of the new management regime. The increased storage capacity in the Upper Columbia dams afforded river managers a much greater degree of control over the river's hydrograph[63]. Peak flows could now be more dramatically reduced, and low flows bolstered by controlled releases from storage. Peak power demands tend to occur in midwinter and midsummer, so river managers calibrate releases to coincide with periods of high demand [64]. This is a dramatic change from the snowmelt-driven summer peak flows of the river prior to its development.

See also

- Hydroelectric dams on the Columbia River

- B.C. Hydro and Power Authority, Provincially owned power utility and owner/operator of Mica, Arrow, & Duncan dams

- Columbia Basin Trust, province of British Columbia effort to mitigate impacts of the treaty

- Columbia Power Corporation, a province owned crown corporation and sister agency with CBT.

- Bonneville Power Administration, U.S. federal agency managing sale and transmission of federal power in the Pacific Northwest.

- United States Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. federal agency managing Libby dam and many other public works projects.

- International Joint Commission, binational commission to prevent and resolve U.S. and Canada disputes over boundary waters.

- W. A. C. Bennett, Premier of British Columbia who led the development of dams on the upper Columbia and Peace Rivers

- Grand Coulee Dam, the largest dam on the Columbia River

- Kootenai River, upstream Columbia tributary that begins in Canada, enters U.S., and returns to Canada

References

- ^ Cohen, Stewart (2000). "Climate Change and Resource Management in the Columbia Basin". Water International. 25 (2): 253–272.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ White, Richard (1995). The Organic Machine. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 54.

- ^ a b White (1995). p. 56.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ White (1995). p. 65.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Swainson, Neil (1979). Conflict Over the Columbia: The Canadian Background to an Historic Treaty. p. 41.

- ^ White (1995). p. 77.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Mitchell, David J. (1983). W.A.C. Bennett & The Rise of B.C. Vancouver/Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre. p. 303. ISBN 0-88894-395-4.

- ^ Mitchell (1983). p. 297.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Loo, Tina. (2004). "PEOPLE IN THE WAY: Modernity, Environment, and Society on the Arrow Lakes". BC Studies (142/143): 161–196. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mitchell (1983). p. 300.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Mitchell (1983). p. 325.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Mitchell (1983). p. 323.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Mitchell (1983). p. 326.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Columbia River Treaty Signed: U.S., Canada Pledge Resource Development", Fairbanks (Alaska) Daily News-Miner. January 17, 1961. Page A1.

- ^ Mitchell (1983). p. 303.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Columbia Basin Trust. "Who Implements the Columbia River Treaty?". Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ Powerex. "Power". Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ B.C. Hydro. "BC Hydro Annual Report 2011" (PDF). Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ "Columbia River Treaty 2014/2024 Review Phase 1 Report" (PDF). Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ Boyer, David S. (December 1974). "Powerhouse of the Northwest". National Geographic. p. 833.

- ^ Stanley, Meg (2012). Harnessing The Power: Voices from Two Rivers of the Peace and Columbia. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre Publishers Inc. p. 232.

- ^ a b Stanley (2012). p. 233.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stanley (2012). p. 5.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stanley (2012). p. 231.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Wilson, J. W. (1973). People in the Way. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-8020-5285-1.

- ^ Stanley (2012). p. 230.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Wilson (1973). p. 78.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stanley (2012). p. 236.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Wilson (1973). p. 89.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Pryce, Paula (1999). Keeping the Lakes' Way: Reburial and the Re-creation of a Moral World among an Invisible People. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 87–98.

- ^ Pryce (1999). p. 87.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c Stanley (2012). p. 234.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c Krutilla, John V. (1967). The Columbia River Treaty: The Economics of an International River Basin Development. Baltimore, MD: Published for Resources for the Future by Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 191–204.

- ^ a b c d e f g "History of the Columbia River Treaty" (PDF). Columbia Basin Trust. 2008–2011. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b "An Overview: Columbia River Treaty" (PDF). Columbia Basin Trust. 2008–2011. Retrieved 19 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j Poole, Mike (Director) (1974). Sunday Best: The Columbia River Treaty (Film). British Columbia: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

{{cite AV media}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ Parr, Joy (2010). Sensing Changes: Technologies, Environments and the Everyday. Vancouver: UBC Press. p. 108.

- ^ Parr (2010). p. 122.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Parr (2010). p. 124.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Parr (2010). pp. 104, 132.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Stanley (2011). p. 192.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Waterfield, Donald (1970). Continental Waterboy. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin & Company. p. 50.

- ^ Stanley (2011). p. 106.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stanley (2011). p. 111.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stanley (2011). p. 147.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stanley (2011). p. 142.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Bullard, Oral (1968). Crisis on the Columbia. Portland, Oregon: The Touchstone Press. p. 105.

- ^ Bullard (1968). p. 114.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Bullard (1968). p. 120.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stanley, Meg (2011). Voices from Two Rivers: Harnessing the Power of Peace and Columbia. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre.

- ^ Parr (2010). p. 126.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c d "Spawning Channels". BC Ministry of Environment. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ a b Masters, Sally. "BC Hydro Supports Creston Valley Wildlife Management Area". BC Hydro. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ "Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program". BC Hydro. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ Van Huizen, Phil (2010). "Building a Green Dam: Environmental Modernism and the Canadian-American Libby Dam Project". Pacific Historical Review. 76 (3): 418–453.

{{cite journal}}: Text "pp. 439" ignored (help) - ^ Van Huizen (2010). : 444.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b c Bullard, Oral (1968). Crisis on the Columbia. Portland, Oregon: The Touchstone Press. p. 18.

- ^ Bullard (1968). p. 106.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Bullard (1968). p. 17.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Bullard (1968). p. 20.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Bullard (1968). p. 99.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Van Huizen (2010). : 452.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Cohen, Stewart (2000). "Climate Change and Resource Management in the Columbia River Basin". Water International. 25 (2): 253–272.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cohen (2000). : 256.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- "The Columbia Basin and the Columbia River Treaty, Canadian Perspectives in the 1990s", 1996 by Nigel Bankes

- "Conflict Over the Columbia, The Canadian Background to an Historic Treaty", 1979 by Neil A. Swainson

- "The Canada/U.S. Controversy Over the Columbia", 1966 Washington Law Review, by Ralph W. Johnson

- "The Columbia River Treaty, the Economics of an International River Basin Development", 1967 by John V. Krutilla

- "The Columbia River Treaty and Protocol, A Presentation", "Appendix", and "Related Documents", 1964 Publications by Canadian Dept. External Affairs and Dept. of Northern Affairs and National Resources.

External links

- [1] Columbia River Treaty Permanent Engineering Board

- [2] Columbia River Treaty, by the British Columbia Ministry of Energy Mines & Petroleum Resources

- [3] Columbia River Treaty History and 2014/2024 Review, by Bonneville Power Administration and US Army Corps of Engineers

- [4] US Northwest Power & Conservation Council article about the Treaty

- Canadian Columbia River Forum

- [5] Columbia Basin Trust

- [6] The Columbia River Treaty

- Binus, Joshua (2004). "Columbia River Treaty: O.K., it's a deal". Oregon Historical Society.

- Text of the Columbia River Treaty Center for Columbia River History,

- Papers of Arthur Paget concerning the Columbia River Treaty Project, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library