Carpal bones

| Carpals | |

|---|---|

| |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ossa carpi |

| MeSH | D002348 |

| TA98 | A02.4.08.001 |

| TA2 | 1249 |

| FMA | 23889 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

Carpus is anatomical assembly connecting the hand to forearm. In human anatomy, the main role of the carpus is to facilitate effective positioning of the hand and powerful use of the extensors and flexors of the forearm, but the mobility of individual carpal bones increase the freedom of movements at the wrist.[1]

In tetrapods, the carpus is the sole cluster of bones in the wrist between the radius and ulna and the metacarpus. The bones of the carpus do not belong to individual fingers (or toes in quadrupeds), whereas those of the metacarpus do. The corresponding part of the foot is the tarsus. The carpal bones allow the wrist to move and rotate vertically.[1]

Etymology

The Latin word "carpus" is derived from Greek καρπὁς meaning "wrist". The root "carp-" translates to "pluck", an action performed by the wrist. [2]

As a whole

In human anatomy, the carpal bones can be classified as belonging to two transverse rows or three longitudinal columns.

The pair of rows together form an arch which is convex proximally and concave distally. On the palmar side, the carpus is concave, forming the carpal tunnel which is covered by the flexor retinaculum. [3] Because the proximal row is simultaneously related to the articular surfaces of the radius and the distal row, it adapts constantly to these mobile surfaces. The bones of this row - scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum - have their individual movements. The scaphoid contributes to the stability of the midcarpus as it articulates distally with the trapezium and the trapezoid. The distal row is more rigid as its transverse arch moves with the metacarpals. [4]

Biomechanically and clinically, the carpal bones are better understood as arranged in three longitudinal columns:[5]

- A radial scaphoid column consisting of the scaphoideum, trapezium, and trapezoideum

- A lunate column consisting of the lunate and capitate

- A ulnar triquetral column consisting of the triquetrum and hamatum.

In this context the pisiform is regarded as a sesamoid bone embedded in the tendon of the flexor carpi ulnaris.[5] The ulnar column leaves a gap between the ulna and the triquetrum, and therefore, only the radial or scaphoid and central or capitate columns articulate with the radius. The wrist is more stable in flexion than in extension more because of the strength of various capsules and ligaments than the interlocking parts of the skeleton. [4]

Ligaments

There are four groups of ligaments in the region of the wrist:[6]

- The ligaments of the wrist proper which unite the ulna and radius with the carpus: the ulnar and radial collateral ligaments; the palmar and dorsal radiocarpal ligaments; and the palmar ulnocarpal ligament.

- The ligaments of the intercarpal articulations which unite the carpal bones with one another: the radiate carpal ligament; the dorsal, palmar, and interosseous intercarpal ligaments; and the pisohamate ligament,

- The ligaments of the carpometacarpal articulations which unite the carpal bones with the metacarpal bones: the pisometacarpal ligament and the palmar and dorsal carpometacarpal ligaments

- The ligaments of the intermetacarpal articulations which unite the metacarpal bones: the dorsal, interosseous, and palmar metacarpal ligaments

Movements

The hand is said to be in straight position when the third finger runs over the capitate bone and is in a straight line with the forearm. This should not be confused with the midposition of the hand which corresponds to an ulnar deviation of 12 degrees. From the straight position two pairs of movements of the hand are possible: abduction (movement towards the radius, so called radial deviation or abduction) of 15 degrees and adduction (movement towards the ulna, so called ulnar deviation or adduction) of 40 degrees when the arm is in strict supination and slightly greater in strict pronation. [7] Flexion (tilting towards the palm, so called palmar flexion) and extension (tilting towards the back of the hand, so called dorsiflexion) is possible with a total range of 170 degrees. [8]

Radial abduction/ulnar adduction

During radial abduction the scaphoid is tilted towards the palmar side which allows the trapezium and trapezoid to approach the radius. Because the trapezoid is rigidly attached to the second metacarpal bone to which also the flexor carpi radialis and extensor carpi radialis are attached, radial abduction effectively pulls this combined structure towards the radius. During radial abduction the pisiform traverses the greatest path of all carpal bones. [7] Radial abduction is produced by (in order of importance) extensor carpi radialis longus, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus, flexor carpi radialis, and flexor pollicis longus. [9]

Ulnar adduction causes a tilting or dorsal shifting of the proximal row of carpal bones.[7] It is produced by extensor carpi ulnaris, flexor carpi ulnaris, extensor digitorum, and extensor digiti minimi.[9]

Both radial abduction and ulnar adduction occurs around a dorsopalmar axis running through the head of the capitate bone. [7]

Palmar flexion/dorsiflexion

During palmar flexion the proximal carpal bones are displaced towards the dorsal side and towards the palmar side during dorsiflexion. While flexion and extension consist of movements around a pair of transverse axes — passing through the lunate bone for the proximal row and through the capitate bone for the distal row — palmar flexion occurs mainly in the radiocarpal joint and dorsiflexion in the midcarpal joint. [8]

Dorsiflexion is produced by (in order of importance) extensor digitorum, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor indicis, extensor pollicis longus, and extensor digiti minimi. Palmar flexion is produced by (in order of importance) flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor digitorum profundus, flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor pollicis longus, flexor carpi radialis, and abductor pollicis longus. [9]

Combined movements

Combined with movements in both the elbow and shoulder joints, intermediate or combined movements in the wrist approximate those of a ball-and-socket joint with some necessary restrictions, such as maximum palmar flexion blocking abduction.[8]

Accessory movements

Anteroposterior gliding movements between adjacent carpal bones or along the midcarpal joint can be achieved by stabilizing individual bones while moving another (i.e. gripping the bone between the thumb and index finger). [10]

Individual bones

Almost all carpals (except the pisiform) have six surfaces. Of these the palmar or anterior and the dorsal or posterior surfaces are rough, for ligamentous attachment; the dorsal surfaces being the broader, except in the lunate.

The superior or proximal, and inferior or distal surfaces are articular, the superior generally convex, the inferior concave; the medial and lateral surfaces are also articular where they are in contact with contiguous bones, otherwise they are rough and tuberculated.

The structure in all is similar: cancellous tissue enclosed in a layer of compact bone.

| Name | Proximal/radial articulations |

Lateral/medial articulations |

Distal/metacarpal articulations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal row | |||

| Scaphoid | radius | capitate, lunate | trapezium, trapezoid |

| Lunate | radius, articular disk | scaphoid, triquetral | capitate, hamate (sometimes) |

| Triquetrum | articular disk | lunate, pisiform | hamate |

| Pisiform | triquetral | ||

| Distal row | |||

| Trapezium | scaphoid | trapezoid | first and second metacarpal |

| Trapezoid | scaphoid | trapezium, capitate | second metacarpal |

| Capitate | scaphoid, lunate | trapezoid, hamate | third, partly second and fourth metacarpal |

| Hamate | triquetral, lunate | capitate | fourth and fifth |

Created from the initial letter of each of the eight carpal bones, in the order most commonly referenced, the sentence "some lovers try positions that they can't handle" is used as a mnemonic device. Another mnemonic is So Long To Pinky, Here Comes The Thumb [12]

Accessory bones

Occasionally accessory bones are found in the carpus, but of more than 20 such described bones, only four (the central, styloid, secondary trapezoid, and secondary pisiform bones) are considered to be proven accessory bones. Sometimes the scaphoid, triquetrum, and pisiform bones are divided into two. [3]

Ossification

| Bone | Average | Variation |

|---|---|---|

| Capitate | 2.5 months | 1–6 months |

| Hamate | 4-5.5 months | 1–7 months |

| Triquetrum | 2 years | 5 months to 3 years |

| Lunate | 5 years | 2-5.5 years |

| Trapezium | 6 years | 4–8 years |

| Trapezoid | 6 years | 4–8 years |

| Scaphoid | 6 years | 4–7 years |

| Pisiform | 12 years | 8–12 years |

The carpal bones are ossified endochondrally (from within the cartilage) and the ossific centers appear only after birth. [11] The formation of these centers roughly follows a chronological spiral pattern starting in the capitate and hamate during the first year of life. The ulnar bones are then ossified before the radial bones, while the sesamoid pisiform arises in the tendon of the flexor carpi ulnaris after more than ten years. [13]

Evolutionary variations

The structure of the carpus varies widely between different groups of tetrapods, even among those that retain the full set of five digits. In primitive fossil amphibians, such as Eryops, the carpus consists of three rows of bones; a proximal row of three carpals, a second row of four bones, and a distal row of five bones. The proximal carpals are referred to as the radiale, intermediale, and ulnare, after their proximal articulations, and are homologous with the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetal bones respectively. The remaining bones are simply numbered, as the first to fourth centralia (singular: centrale), and the first to fifth distal carpals. Primitively, each of the distal bones appears to have articulated with a single metacarpal.

However, the vast majority of later vertebrates, including modern amphibians, have undergone varying degrees of loss and fusion of these primitive bones, resulting in a smaller number of carpals. Almost all mammals and reptiles, for example, have lost the fifth distal carpal, and have only a single centrale - and even this is missing in humans. The pisiform bone is somewhat unusual, in that it first appears in primitive reptiles, and is never found in amphibians.

Because many tetrapods have less than five digits on the forelimb, even greater degrees of fusion are common, and a huge array of different possible combinations are found. The wing of a modern bird, for example, has only two remaining carpals; the radiale (the scaphoid of mammals) and a bone formed from the fusion of four of the distal carpals.[14]

In some macropods, the scaphoid and lunar bones are fused into the scapholunar bone.[15]

In crustaceans, "carpus" is the scientific term for the claws or "pincers" present on some legs. (See Decapod anatomy.)

Gallery

-

Carpal bones.

-

Carpal bones detailed.

-

Scaphoid bone.

-

Lunate bone.

-

Triquetral bone.

-

Pisiform bone.

-

Trapezium bone.

-

Trapezoid bone.

-

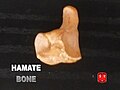

Capitate bone.

-

Hamate bone.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Kingston 2000, pp 126-127

- ^ Diab 1999, p 48

- ^ a b Platzer 2004, p 124

- ^ a b Schmidt-Lanz 2003, p 29

- ^ a b Thieme Atlas of Anatomy 2006, p 224

- ^ Platzer 2004, p 130

- ^ a b c d Platzer 2004, p 132

- ^ a b c Platzer 2004, p 134

- ^ a b c Platzer 2004, p 172

- ^ Palastanga 2006, p 184

- ^ a b Platzer 2004, p 126

- ^ "Anatomy Mnemonics". The Doctors Lounge. Retrieved July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Schmidt, Hans-Martin; Lanz, Ulrich (2003). Surgical Anatomy of the Hand. Thieme. p. 7. ISBN 1-58890-007-X.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 200–202. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ Swamp Wallaby (Wallabia bicolor) carpals

References

- Diab, Mohammad (1999). Lexicon of Orthopaedic Etymology. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 90-5702-597-3.

- Kingston, Bernard (2000). Understanding joints: a practical guide to their structure and function. Nelson Thornes. ISBN 0-7487-5399-0.

- Palastanga, Nigel (2006). Anatomy and human movement: structure and function. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 0-7506-8814-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

- Schmidt, Hans-Martin; Lanz, Ulrich (2003). Surgical anatomy of the hand. Thieme. ISBN 1-58890-007-X.

- Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. 2006. ISBN 1-58890-419-9.

External links

- Anatomy photo:08:os-0101 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Palm of the Hand: Carpal bones"

- Hand kinesiology at the University of Kansas Medical Center