Siege of Vienna (1485)

| Siege of Vienna | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Austrian-Hungarian War (1477-1488) | |||||||

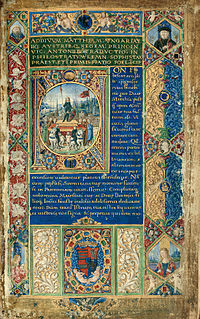

Matthias marching into Vienna | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Hanns von Wulfestorff[1] Caspar von Lamberg[c] Bartholomeus von Starhemberg[c] Andreas Gall[c] Ladislaus Prager[c] Alexander Schiffer[c] Tiburtius von Linzendorf[c] Leonhard Fruhmann[c] Johann Karrer[c] |

Matthias Corvinus[d] Peter Geréb de Vingard [d] Stefan Zápolya[d] Stephen V Báthory[2] Laurence of Ilok[d] | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Imperial Army | Black Army of Hungary | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2,000 foot soldiers 1,000 cavalry[3] 20,000 civilians[4] reinforcements: 200 cavalry 300 fusiliers 60 archers[a] |

10,000 foot soldiers 18,000 cavalry[5] | ||||||

The Siege of Vienna was a decisive siege of the Austro-Hungarian War in 1485. It was a consequence of the ongoing conflict between Frederick III and Matthias Corvinus. The fall of Vienna meant its merging to Hungary from 1485 to 1490. Matthias Corvinus also moved his royal court to the newly occupied city.

The siege

In the year 1483-84 Vienna was being already cut from the Empire since all of his concentric defense ring had fallen namely Korneuburg, Bruck, Hainburg and later Kaiserebersdorf. One of the most important battle was Battle of Leitzersdorf, which prepared the possibility of the siege in the next year.[6] City was perished by famine though Emperor Frederick III succeeded in providing some vital supplies with a breakthrough of sixteen vessels on the Danube to the city. On the 15th January, Matthias called the city to surrender but captain von Wulfestorff refused to do so in a hope of an Imperial relief. The blockade was fully sealed when Matthias attacked Kaiserebersdorf. There he was an unaware subject of an assassination attempt when a cannonball nearly killed him. He suspected of treachery as the aim was too precise from a long distance that only one who knew the whereabouts of the King could fire it so. He accused Jaroslav von Boskowitz und Černahora of bribery who was the brother of his mercenary captain Tobias von Boskowitz and Černahora. Without any chance to clear himself Jaroslav was decapitated.[7] His brother Tobias was became so frustrated he returned to the service of Frederick and led his campaigns of reconquer after the death of Matthias in 1490. After Kaiserebersdorf was captured in mid-1485 the fate of Vienna turned inevitable.

Matthias placed his armies on the Hundsmühle flour mills and in Gumpeudorf on the south of the Wien River[b]The King previously imported seventeen siege guns to Austria,[8] and ordered the constant shooting of the city and the construction of two siege towers one of which had been burnt by the resisting militia of Vienna.[1] Matthias intruded into Leopoldstadt in May 15 [7] that made the final assault feasible. The Viennese people realized this and negotiated to deliver the inner city to the Hungarian King. Their only condition was the reassurance of their citizen privileges and a free passage. On 1 June in head of a military parade Matthias entered the downtown fort.[8]

Aftermath

In the Salzburg manifest Frederick ordered the Austrian States to refuse Matthias' demand for the assembly of an Imperial Congress. He also put forward that soon to be Emperor Maximilian I would come to an aid. According to tradition this is the origin of A.E.I.O.U. a said to be secret message to all Austrian provinces. At the end of the Matthias' campaign Hungary controlled all of Upper Austria as well and remained under his control to his death in 1490.[8]

Administrative issues

Matthias deprived Vienna of its staple right, a right that violated the commercial interests of the nearby countries so much, they formed the Visegrád Group to secure a bypass route detouring the city. The city in counterpart enjoyed a tax free status under Matthias rule. He also delegated a member, Stefan Zápolya to the Council of Vienna but left the rest of city fathers intact. He rewarded him the city of Ebenfurth[9] and appointed him as the captain of Vienna and governor of the Austrian provinces incorporated into Hungary.[10] The bishop of Pécs Sigismund Ernust was promoted the vice-governor while Nikolaus Kropatsch took care of the military affairs. The prominent captains received houses in Vienna.[11]

Footnotes

- a Geissau[12] pp. 35

- b Geissau pp. 36–37 (Hundsmühle and Heumühle were Middle age flour mills in Vienna next to the "Am Gries" marshes on the right bank of the Wien river)[13]

- c Geissau pp. 41–42

- d Geissau pp. 52

References

- ^ a b István Diós (1993). "Magyar Katolikus Lexikon". lexikon.katolikus.hu (in Hungarian). Budapest, Hungary: Szent István Társulat. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ István Draskóczy (2009). "Középkori magyar történeti kronológia a kombinált vizsga írásbeli részéhez". http://tortenelemszak.elte.hu - ELTE BTK Történelem Szakos Portál (in Hungarian). Budapest, Hungary: ELTE BTK - ponte.hu Kft. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work=|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Ignatius Aurelius Fessler (1822). Die geschichten der Ungern und ihrer landsassen (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Johann Friedrich Gleditsch. p. 384. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Johannes Sachslehner (2008-06-30). "STEP 05 – a jövőbe vezető út". wieninternational.at/ Vienna's weekly European journal (in Hungarian). Vienna, Austria: Compress VerlagsgesmbH & Co KG. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Andrew Ayton (1998). "The Military Revolution from a Medieval Perspective". The Medieval Military Revolution: State, Society and Military Change in Medieval and Early Modern Society. London, England: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-353-1. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ http://lexikon.katolikus.hu/B/B%C3%A9cs%20ostroma.html

- ^ a b József Bánlaky (1929). "b) Az 1483–1489. évi hadjárat Frigyes császár és egyes birodalmi rendek ellen. Mátyás erőlködései Corvin János trónigényeinek biztosítása érdekében. A király halála.". A magyar nemzet hadtörténelme (in Hungarian). Budapest, Hungary: Grill Károly Könyvkiadó vállalata. ISBN 963-86118-7-1. Retrieved 27 June, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Charlotte Mary Yonge (1874). "Sketches from Hungarian History". The Monthly packet. London, United Kingdom: J. and C. Mozley.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lajos Gerő (1893). "Szapolyai". Pallas Nagylexikon (in Hungarian). Budapest, Hungary: Pallas Irodalmi és Nyomdai Rt. ISBN 963-85923-2-X. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ Tamás Tarján. "Mátyás király elfoglalja Bécs városát". Rubicon Journal. Budapest, Hungary: Rubicon-Ház Bt. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Tamás Fedeles (2009). "Mátyás szolgálatában". Ernuszt Zsigmond pécsi püspök (1473-1505) (in Hungarian). Szekszárd, Hungary: Schöck Kft. p. 7. ISBN 978-963-06-7663-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Anton Ferdinand von Geissau (1805). Geschichte der Belagerung Wiens durch den König Mathias von Hungarn, in den Jahren 1484 bis 1485 (in German). Wien, Austria: Anton Strauss. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gries, Kies, Ufersand". Aeiou Encyclopedia. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)