Battle of Leipzig

| Battle of Leipzig | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Sixth Coalition | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

(18–19 October)[1] | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

380,000[2]

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

44,000 dead and wounded 36,000 captured | 54,000 dead, wounded or missing[2] | ||||||

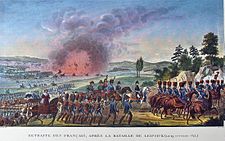

The Battle of Leipzig or Battle of the Nations, on 16–19 October 1813, was fought by the coalition armies of Russia, Prussia, Austria and Sweden against the French army of Napoleon at Leipzig, Saxony. Napoleon's army also contained Polish and Italian troops as well as Germans from the Confederation of the Rhine. The battle marked the culmination of the fall campaign of 1813 during the German campaign and involved over 600,000 soldiers, making it the largest battle in Europe prior to World War I.

Defeated, Napoleon was compelled to return to France while the Allies hurried to keep their momentum, invading France early the next year. Napoleon was forced to abdicate, and was exiled to Elba that spring.

Prelude

Following Napoleon's failed invasion of Russia and his defeats in the Peninsular War, the anti-French forces had cautiously regrouped as the Sixth Coalition, comprising Russia, Austria, Prussia, Sweden, Britain, Spain, Portugal and certain smaller German states. In total, the Coalition could put into the field well over a million troops; indeed by the time of Leipzig, total Allied armies east of the Rhine probably exceeded a million. By contrast Napoleon's forces had shrunk to just a few hundred thousand.

Napoleon sought to re-establish his hold in Germany, winning two hard-fought victories, at Lützen on 2 May and Bautzen on 20–21 May, over Russo-Prussian forces. The victories led to a brief armistice. He then won a major victory at Dresden on 27 August. Following this, the Coalition forces, under the chief command of Russian General Barclay de Tolly and individual command of Gebhard von Blücher, Crown Prince Carl Johan of Sweden and Karl von Schwarzenberg, and Count Benningsen of Russia followed the strategy outlined in the Trachenberg Plan to avoid clashes with Napoleon but to seek confrontations with his marshals, which led to victories at Großbeeren, Kulm, Katzbach and at Dennewitz.

Marshal Nicolas Oudinot was defeated at the Battle of Großbeeren and thus failed to capture Berlin with his army of 60,000. This forced Napoleon to withdraw westwards because of the threat to the north, crossing the Elbe in late September and organising his forces around Leipzig to protect his supply lines and meet the Allies. Napoleon deployed his army around the city, but concentrated his force from Taucha through Stötteritz, where he placed his command. The Prussians advanced from Wartenburg, the Austrians and Russians from Dresden and the Swedish force from the north.

Opposing forces

The French had around 160,000 soldiers along with 700 guns plus 15,000 Poles, 10,000 Italians, and 40,000 Germans belonging to the Confederation of the Rhine, totaling to 225,000 troops on the Napoleonic side. The Coalition, on the other hand has some 380,000 troops along with 1,500 guns fielded in the battle consisting of 145,000 Russians, 110,000 Austrians and Hungarians, 90,000 Prussians, and 30,000 Swedes. This makes the largest battle since Borodino, Wagram, Jena and Auerstadt, and Ulm.

The French Grande Armée, under the supreme command of Emperor Napoleon, was in a complacent state; most of his troops consisted of teens and inexperienced men conscripted shortly after the utter destruction of Grande Armée during Napoleon's ill-fated invasion of Russia. Napoleon conscripted these men to be readied for an even larger campaign against the newly-formed Sixth Coalition and its forces stationed in Germany. Whilst he won the battles at Lützen and Bautzen, his army was steadily depleting as Grande Armée forces were seemingly defeated in some battles commanded by Napoleon's marshals while the commanders of the Coalition forces closely followed the Trachenberg Plan. The French Imperial cavalry was also in a complacent state; they were of poor quality compared to those who were mobilized during the Russian campaign. This was the reason why Napoleon could not keep his eyes on his lines of communications or scout some enemy positions, the fact that fruited during the battle at Grossbeeren, a settlement just south of Berlin.

The Coalition army, under the overall supreme command of tsar Alexander I of Russia and Russian Field Marshal Prince Barclay de Tolly and Austria's Karl von Schwarzenberg as the commanders-in-chief of the army, was composed of four army-level commands: the Austrian Army of Bohemia under Karl von Schwarzenberg, the Prussian Army of Silesia under Gebhard von Blücher, the Russian Army of Poland under Levin August von Benningsen and the Swedish Army of the North under Charles John Bernadotte.

Strategic situations

Napoleon's plans

Despite being outnumbered, Napoleon planned to take the offensive between the Pleisse and the Parthe rivers. The position at Leipzig offered several advantages for a resourceful commander. The rivers that converged there split the surrounding terrain into many separate sectors. Holding Leipzig and its bridges, Napoleon could shift troops from one sector to another far more rapidly than could the Allies, who had several difficulties commanding huge amounts of troops in a single sector of fighting.[4]

The northern front was defended by marshals Ney and Marmont, and the eastern front by MacDonald. Artillery reserve and parks, ambulances and baggages stood near Leipzig. The bridges on Pleisse and Elster River were defended by infantry and few guns. The main battery stood in reserve, and during battle will be deployed on the Gallows Height. This battery will be commanded by Drouot himself. The western flank of French positions at Wachau and Liebertwolkwitz was defended by Poniatowski and Augereau and his French young conscripts.

Coalition's plans

A substantial staff supported the allied commanders, but their staff was not a smooth running and efficient organization. It was fraught with incompetence and petty rivalries where factions fought each other; its work was as much military as it was toadying to the vanities of the monarchs. At first, many considered Schwarzenberg as the one fit to be the overall supreme commander for the Coalition forces in the battle, but because that Alexander I, the Emperor of Russia, complained about his incompetence in terms of battle planning (his main plan is to call for a secondary attack on the bridge between Leipzig and Lindenau to be led by Blucher and Gyulai, and a main attack astride the Pleisse River to be led by Merveldt, Hessen-Homburg and the Prussian Guard) compared to marshals Prince Volkonsky of Russia, Johan Christopher Toll of Sweden, and Karl Friedrich von dem Knesebeck and Gerhard von Scharnhorst of Prussia, as did most of the command staff, many voted for the Russian tsar Alexander as the rightful one fit for being the overall supreme commander, and so it was, the tsar Alexander became the overall supreme commander of the Coalition Army,[5] but he made Schwarzenberg draft another battle plan that was largely designed to let everyone do as they pleased. Blucher's axis of advance was shifted northward to the Halle road, the Russian and Prussian guards and the Russian heavy cavalry is to be amassed at Rotha in general reserve. The Austrian grenadiers and cuirassiers would advance between the rivers.[5]

16 October

The allied offensives achieved little and were soon forced back, but Napoleon's outnumbered forces were unable to break the allied lines, resulting in a hard fought stalemate.

Austrian II Corps captures Dölitz

The Austrian II Corps, commanded by General von Merveldt, advanced towards Connewitz via Gautzsch and attempted to attack the position by the time Napoleon arrived in the battlefield along with the Young Guard and some Chasseurs, or the Imperial snipers, only to find that the avenue of advance was well covered by French battery and some skirmishers who have occupied the houses there and did not permit the Austrians to deploy their artillery in support of the attack. Repulsed, the Austrians then moved to attack nearby Dölitz, down a road crossed by two bridges and leading to a manor house and a mill. Two companies of the 24th regiment threw out the small Polish garrison and took the position. A prompt counterattack ejected the Austrians and the battle seesawed, until the Austrians brought up a strong artillery battery and blew the Poles out of the position. The Poles left bodies everywhere in their furious defense and set fire to both the manor and the mill on the way out.[6]

Battle of Markkleeberg

General Kleist, moving along the Pleisse River, attacked Marshals Poniatowski and Augereau in the village of Markkleeberg. The Austrians repaired a bridge and took a school building and manor. The French counterattacked, throwing the Austrians out of the school and back over the river. French attacks on the manor only resulted in mounting casualties for the French and Poles. The Russian 14th Division began a series of flanking attacks that forced the Poles out of Markkleeberg. Marshal Poniatowski stopped the retreat and the advancing Russians. Catching four battalions of the Prussian 12th Brigade in the open, Poniatowski directed attacks by artillery and cavalry until they were relieved by Russian hussars. Marshal Poniatowski retook Markkleeberg, but was thrown out by two Prussian battalions. Austrian grenadiers then formed in front of Markkleeberg and drove the Poles and French out of the area with a flank attack.[6]

Attack on Wachau

The Russian II Infantry Corps attacked Wachau near Leipzig with support from the Prussian 9th Brigade. The Russians advanced, unaware that French forces were waiting. The French took them by surprise in the flank, mauling them. The Prussians entered Wachau, engaging in street to street fighting. French artillery blasted the Prussians out of Wachau and the French recovered the village.[7][8]

Battle of Liebertwolkwitz

Liebertwolkwitz was a large village in a commanding position, defended by Marshal MacDonald and General Lauriston with about 18,000 men. Johann von Klenau's Austrian IV Corps attacked with 24,500 backed up by Pirth's 10th Brigade (4,550) and Ziethen's 11th Brigade (5,365). The Austrians attacked first, driving the French out of Liebertwolkwitz after hard fighting, only to be driven out in turn by a French counterattack. At this point, Napoleon directed General Drouot to form a grand battery on Gallows hill. This was done with 100 guns that blasted the exposed Russian II corps, forcing the Prussian battalions supporting it to take cover. Russian General Württemberg was notable for his extreme bravery, directing his troops under fire. The hole had been now opened as Napoleon wished and at this point, Marshal Murat was unleashed with 10,000 French, Italian, and Saxon cavalry. However, Murat's choice of massive columns for the attack formation was unfortunate for the French force, as smaller mobile formations of Russian, Prussian, and Austrian cavalry were able to successfully harass Murat's Division, driving them back to their own artillery, where they were saved by the French Guard Dragoons. The young Guard Division was sent in to drive out the allies and give Napoleon his breakthrough. They recaptured both Liebertwolkwitz and Wachau, but the Allies countered with Russian Guard and Austrian grenadiers backed by Russian cuirassiers. The units lived up to their elite reputation, forming squares that blasted French cavalrymen from their horses and overran the French artillery batteries. On the southern front, although Napoleon gained ground, he could not break the Allied lines.[6]

Northern attack

The northern front opened with the attack by General Langeron's Russian Corps on the villages of Groß-Wiederitzsch and Klein-Wiederitzsch in the center of the French northern lines. This position was defended by General Dabrowski's Polish division of four infantry battalions and two cavalry battalions. At first sign of the attack, the Polish division attacked. The battle wavered back and forth with attacks and counterattacks. General Langeron rallied his forces and finally took both villages with heavy casualties.

Battle of Möckern

The Northern front was dominated by the battle of Möckern. This was a 4 phase battle and saw hard fighting from both sides. A manor, palace, walled gardens, and low walls dominated the village. Each position was turned into a fortress with the walls being loopholed for covered fire by the French. The ground to the west of the position was too wooded and swampy for emplacement of artillery. A dike ran east along the river Elster being 4 meters high. Marshal Auguste Marmont brought up infantry columns behind the positions in reserve and for quick counter-attack against any fallen position. Blücher commanded Langeron's (Russian) and Yorck's (Prussian) corps against Marmont's VI Corps. When the battle hung in the balance, Marmont ordered a cavalry charge, but his commander refused to attack. Later, an attack by Prussian hussars caused serious loss to the French defenders. The battle lasted well into the night. Artillery caused the majority of the 9,000 Allied and 7,000 French casualties, and the French lost another 2,000 prisoners.[9]

17 October

There were only two actions on 17 October: an attack by the Russian General Sacken on General Dabrowski's Polish Division at the village of Gohlis. In the end, the numbers and determination of the Russians prevailed and the Poles retired to Pfaffendorf. Blücher, who was made a field marshal the day before, ordered General Lanskoi's 2nd Hussar Division (Russian) to attack General Arrighi's III Cavalry corps. As they had the day before the Sixth Coalition's cavalry proved to be superior, driving the French away with great loss.

The French received only 14,000 troops as reinforcements. On the other hand, the coalition was strengthened by the arrival of 145,000 troops, including those commanded by Russian General von Bennigsen and Prince Charles John of Sweden, who was the late ex-French Marshal Jean Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, formerly one of Napoleon's most trusted field marshals.

18 October

Napoleon's attempt to sue for armistice

It is evident that the Allies will encircle Napoleon and his army, and he knew that not retreating from the battle would mean capitulation for his entire army. So Napoleon began to examine whether the roads and bridges of Lindenau could be used to withdraw his troops, or at the very least to secure a bridgehead crossing on the Pleisse River. However, he is not yet in the mood to withdrawing as he thought that this day is the day he will achieve one more great victory for France. He also thought that a strong, formidable rear guard in Leipzig itself could repulse any Allied assault, which could buy him and his forces more time to withdraw from the battle.

During this time Napoleon sent General Merveldt back to the Allies on parole. Merveldt was given a letter to the Austrian Emperor Francis I in which Napoleon offered to surrender to the Coalition the fortresses he held along the Oder and Vistula, on the condition that the allies allow him to withdraw to a position behind the Saale. He added that, if approved, they should sign an armistice and undertake peace negotiations. However, Francis declined the offer.[10]

Coalition armies encircle Napoleon

The Allies launched a huge assault from all sides. In over nine hours of fighting, in which both sides suffered heavy casualties, only the resilience and bravery of the French troops prevented a breakthrough, but were slowly forced back towards Leipzig. The Sixth Coalition had Field Marshal Blücher (Prussian) and Prince Charles John of Sweden to the north, the Generals Barclay De Tolly, Bennigsen (both Russian) and Prince von Hessen-Homburg (Austrian) to the south, and Ignaz Gyulai (Austrian) to the west.

The Prussian 9th brigade occupied the abandoned village of Wachau while the Austrians, with General Bianchi's Hungarians, threw the French out of Lößnig. The Austrians proceeded to give a demonstration of combined arms cooperation as Austrian cavalry attacked French infantry to give Austrian infantry time to arrive and deploy in the attack on Dölitz. The Young Guard Division threw them out. At this point, three Austrian grenadier battalions began to contest for the village with artillery support.[11]

Saxony defects to the Coalition

During the fighting, 5,400 Saxons of Jean Reynier's VII Corps defected to the Coalition. At first French officers saw the Saxons' rushing towards the advancing Prussians as a charge, but treachery became evident as they saw the Saxons asking the Prussians to join with them for the impending assault. Reynier himself witnessed this, and he rallied the remaining Saxons at his disposal, but to no avail, because Wurttemburg's cavalry also deserted from the French; this forced the French line in Paunsdorf to fall back.[12]

Swedes participate at the final assault

In the meantime, at the behest of his Swedish officers, who felt embarrassed that they had not participated in the battle, the Crown Prince Charles John gave the order for his light infantry to participate in the final assault on Leipzig itself. The Swedish jägers performed very well, losing only about 121 men in the attack.

19 October

19 October, the fourth day of the battle. Napoleon saw that the battle was a lost cause and on the night of 18–19 October, he began to withdraw the majority of his army across the river Elster. But before this, he promoted Poniatowski to the rank of Maréchal d'Empire, the only foreigner of all his marshals who was given this title, and the latter swore that he will fight to the last stand, which he did.[13] The Allies did not learn of the evacuation until 7:00 in the morning, and were then held up by Oudinot's ferocious street-to-street rearguard action in Leipzig. As the Russian and Prussian troops entered Leipzig via the Grimma Gate, they stormed the houses and barricades full of enemy soldiers. The civilians in the city went into hiding as bloody urban combat raged on.[14]

The retreat went smoothly until early afternoon when the general tasked with destroying the only bridge over the Elster delegated the task to a Colonel Montfort. The colonel in turn passed this responsibility on to a corporal, who, unaware of the carefully planned time schedule, ignited the fuses at 1:00 in the afternoon, when the bridge was still crowded with French troops, and Oudinot's rearguard was still in Leipzig. The explosion and subsequent panic and rout resulted in the deaths of thousands of French troops, and the capture of many thousands more. During that event, Poniatowski, the Polish leader, drowned while crossing the river.[15]

Results

The battle of Leipzig is the bloodiest in the history of Napoleonic Wars because casualties on both sides were astoundingly high; estimates range from 80,000 to 110,000 total killed, wounded or missing. Napoleon lost about 45,000 killed and wounded. The Allies captured 15,000 able-bodied Frenchmen, 21,000 wounded or sick, 325 cannon and 28 eagles, standards or colours, and had received the men of the deserting Saxony divisions. Among the dead was Marshal Józef Antoni Poniatowski, a nephew to the last king of Poland, Stanisław August Poniatowski. The Pole, who had received his marshal's baton just the previous day, was commanding the rear guard during the French retreat and drowned as he attempted to cross the river. Corps commanders Lauriston and Reynier were captured. Fifteen French generals were killed and 51 wounded.

Out of a total force of 380,000, the Allies suffered approximately 54,000 casualties. Schwarzenberg's Bohemian Army lost 34,000, Blücher's Silesian Army lost 12,000, while Bernadotte's Army of the North and Bennigsen's Army of Poland lost about 4,000 each. The number of casualties the Coalition army suffered made it impossible for them to pursue the retreating Grande Armee, but the French themselves were already exhausted after the battle, and they hurried back to France to begin their hard-fought defense until the early spring of 1814.

Aftermath

The battle ended the First French Empire's presence east of the Rhine and brought the German states over to the Coalition. It also dealt a harsh blow against Napoleon himself, who was decisively defeated in battle for the first time ever in the history of the Napoleonic Wars. He and his army were already fleeing ahead with his army back to France to muster its defense against the now-invading Coalition forces. With the battle ended with the Coalition nations as the victors, the German Campaign ended in a complete failure for the French, although they achieved a minor victory when an army of Kingdom of Bavaria attempted to block the retreat of the Grande Armée at Hanau. But, more importantly, French forces will never enter Germany until at least World War I.

With the Kingdom of Italy now abolished and German states of the Confederation of the Rhine defecting to the Coalition cause, the Coalition pressed its advantage and invaded France in early 1814. Napoleon was forced from the throne of France and exiled to the island of Elba, and the First French Empire capitulated for the first time.

In addition to the 91 m high Völkerschlachtdenkmal, the course of the battle in the city of Leipzig is marked by numerous monuments and the 50 Apel Stones that mark important lines of the French and Allied troops.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Defected to the allies 18 October 1813

- ^ a b c Chandler 1966, p. 1020

- ^ a b "Leipzig : Battle of Leipzig : Napoleonic Wars : Bonaparte : Bernadotte : Charles : Blucher". Napoleonguide.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Digby Smith, "1813: Leipzig - Napoleon and the Battle of the Nations"

- ^ a b (Esposito & Elting - "Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic wars."

- ^ a b c Battle of Leipzig 1813 : Battle of Nations : Napoleon : Schlacht : Bataille[dead link]

- ^ Battle of Leipzig 1813 : Battle of Nations : Napoleon : Schlacht : Bataille[dead link]

- ^ William Cathcart (first edition 1850) Commentaries on the War in Russia and Germany in 1812 and 1813, London: J. Murray. Reissue: Demi-Solde Press, ISBN 1-891717-14-6.

- ^ Battle of Leipzig 1813 : Battle of Nations : Napoleon : Schlacht : Bataille[dead link]

- ^ Nafziger - "Napoleon at Leipzig", p. 191

- ^ Battle of Leipzig 1813 : Battle of Nations : Napoleon : Schlacht : Bataille[dead link]

- ^ Howard Giles, unknown book and date of publishing

- ^ Bowden - "Napoleon's Grande Armee of 1813" 1990, p. 191

- ^ Digby Smith - "1813: Leipzig - Napoleon and the Battle of the Nations", p. 256

- ^ Chandler, 1966,p 936

References

- Chandler, David G. (1966), The Campaigns of Napoleon, The MacMillan Company;

- Smith, Digby (1998), The Napoleonic Wars Data Book, Greenhill

External links

- “Easily ranking as one of the largest battles in History”

- Allied Order-of-Battle at Leipzig: 16-18 October 1813

- French order of battle: II–XI Army Corps

- French order of battle: Cavalry Reserve and the Imperial Guard

- Template:De icon http://www.voelkerschlacht1813.de/

- Template:De icon http://www.voelkerschlacht-bei-leipzig.de/

- Template:De icon http://www.leipzig1813.com

- Battles involving Austria

- Battles involving France

- Battles involving Poland

- Battles involving Prussia

- Battles involving Russia

- Battles involving Saxony

- Battles involving Sweden

- Battles of the Napoleonic Wars

- Battles of the War of the Sixth Coalition

- Conflicts in 1813

- 1813 in Austria

- 1813 in France

- 1813 in Germany