Angular momentum

| Part of a series on |

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

In physics, angular momentum, moment of momentum, or rotational momentum[1][2] is a vector quantity that represents the product of a body's rotational inertia and rotational velocity about a particular axis. The angular momentum of a system of particles (e.g. a rigid body) is the sum of angular momenta of the individual particles. For a rigid body rotating around an axis of symmetry (e.g. the blades of a ceiling fan), the angular momentum can be expressed as the product of the body's moment of inertia, I, (i.e., a measure of an object's resistance to changes in its rotation velocity) and its angular velocity ω:

In this way, angular momentum is sometimes described as the rotational analog of linear momentum.

For the case of an object that is small compared with the radial distance to its axis of rotation, such as a tin can swinging from a long string or a planet orbiting in a circle around the Sun, the angular momentum can be expressed as its linear momentum, mv, crossed by its position from the origin, r. Thus, the angular momentum L of a particle with respect to some point of origin is

Angular momentum is conserved in a system where there is no net external torque, and its conservation helps explain many diverse phenomena. For example, the increase in rotational speed of a spinning figure skater as the skater's arms are contracted is a consequence of conservation of angular momentum. The very high rotational rates of neutron stars can also be explained in terms of angular momentum conservation. Moreover, angular momentum conservation has numerous applications in physics and engineering (e.g., the gyrocompass).

Angular momentum in classical mechanics

Definition

The angular momentum L of a particle about a given origin is defined as:

where r is the position vector of the particle relative to the origin, p is the linear momentum of the particle, and × denotes the cross product.

As seen from the definition, the derived SI units of angular momentum are newton meter seconds (N·m·s or kg·m2/s) or joule seconds (J·s). Because of the cross product, L is a pseudovector perpendicular to both the radial vector r and the momentum vector p and it is assigned a sign by the right-hand rule.

For an object with a fixed mass that is rotating about a fixed symmetry axis, the angular momentum is expressed as the product of the moment of inertia of the object and its angular velocity vector:

where I is the moment of inertia of the object (in general, a tensor quantity), and ω is the angular velocity.

The angular momentum of a particle or rigid body in rectilinear motion (pure translation) is a vector with constant magnitude and direction. If the path of the particle or center of mass of the rigid body passes through the given origin, its angular momentum is zero.

Angular momentum is also known as moment of momentum.

Angular momentum of a collection of particles

If a system consists of several particles, the total angular momentum about a point can be obtained by adding (or in the continuous case, integrating) all the angular momenta of the constituent particles.

i.e.,

Angular momentum simplified using the center of mass

It is very often convenient to consider the angular momentum of a collection of particles about their center of mass, since this simplifies the mathematics considerably. The angular momentum of a collection of particles is the sum of the angular momentum of each particle:

where ri is the position vector of particle i from the reference point, mi is its mass, and vi is its velocity. The center of mass is defined by:

where the total mass of all particles is given by

It follows that the velocity of the center of mass is

If we define Ri as the displacement of particle i from the center of mass, and Vi as the velocity of particle i with respect to the center of mass, then we have

- and

we can see that

- and

thus the total angular momentum with respect to the reference point is

The first term is just the angular momentum of the center of mass. It is the same angular momentum one would obtain if there were just one particle of mass m moving at velocity v located at the center of mass. The second term is the angular momentum that is the result of the particles moving relative to their center of mass. This second term can be even further simplified if the particles form a rigid body, in which case it is the product of moment of inertia and angular velocity of the spinning motion (as above). The same result is true if the discrete point masses discussed above are replaced by a continuous distribution of matter.

Fixed axis of rotation

For many applications where one is only concerned about rotation around one axis, it is sufficient to discard the pseudovector nature of angular momentum, and treat it like a scalar where it is positive when it corresponds to a counter-clockwise rotation, and negative clockwise. To do this, just take the definition of the cross product and discard the unit vector, so that angular momentum becomes:

where θr,p is the angle between r and p measured from r to p; an important distinction because without it, the sign of the cross product would be meaningless. From the above, it is possible to reformulate the definition to either of the following:

where is called the lever arm distance to p.

The easiest way to conceptualize this is to consider the lever arm distance to be the distance from the origin to the line that p travels along. With this definition, it is necessary to consider the direction of p (pointed clockwise or counter-clockwise) to figure out the sign of L. Equivalently:

where is the component of p that is perpendicular to r. As above, the sign is decided based on the sense of rotation.

For an object with a fixed mass that is rotating about a fixed symmetry axis, the angular momentum is expressed as the product of the moment of inertia of the object and its angular velocity vector:

where I is the moment of inertia of the object (in general, a tensor quantity) and ω is the angular velocity.

It is a misconception that angular momentum is always about the same axis as angular velocity. Sometime this may not be possible, in these cases the angular momentum component along the axis of rotation is the product of angular velocity and moment of inertia about the given axis of rotation.

As the kinetic energy K of a massive rotating body is given by

it is proportional to the square of the angular velocity.

Conservation of angular momentum

The law of conservation of angular momentum states that when no external torque acts on an object or a closed system of objects, no change of angular momentum can occur. Hence, the angular momentum before an event involving only internal torques or no torques is equal to the angular momentum after the event. This conservation law mathematically follows from isotropy, or continuous directional symmetry of space (no direction in space is any different from any other direction). See Noether's theorem.[3]

The time derivative of angular momentum is called torque:

(The cross-product of velocity and momentum is zero, because these vectors are parallel.) So requiring the system to be "closed" here is mathematically equivalent to zero external torque acting on the system:

where is any torque applied to the system of particles. It is assumed that internal interaction forces obey Newton's third law of motion in its strong form, that is, that the forces between particles are equal and opposite and act along the line between the particles.

In orbits, the angular momentum is distributed between the spin of the planet itself and the angular momentum of its orbit:

- ;

If a planet is found to rotate slower than expected, then astronomers suspect that the planet is accompanied by a satellite, because the total angular momentum is shared between the planet and its satellite in order to be conserved.

The conservation of angular momentum is used extensively in analyzing what is called central force motion. If the net force on some body is directed always toward some fixed point, the center, then there is no torque on the body with respect to the center, and so the angular momentum of the body about the center is constant. Constant angular momentum is extremely useful when dealing with the orbits of planets and satellites, and also when analyzing the Bohr model of the atom.

The conservation of angular momentum explains the angular acceleration of an ice skater as she brings her arms and legs close to the vertical axis of rotation. By bringing part of mass of her body closer to the axis she decreases her body's moment of inertia. Because angular momentum is constant in the absence of external torques, the angular velocity (rotational speed) of the skater has to increase.

The same phenomenon results in extremely fast spin of compact stars (like white dwarfs, neutron stars and black holes) when they are formed out of much larger and slower rotating stars (indeed, decreasing the size of object 104 times results in increase of its angular velocity by the factor 108).

The conservation of angular momentum in Earth–Moon system results in the transfer of angular momentum from Earth to Moon (due to tidal torque the Moon exerts on the Earth). This in turn results in the slowing down of the rotation rate of Earth (at about 42 ns/day [citation needed]), and in gradual increase of the radius of Moon's orbit (at ~4.5 cm/year rate [citation needed]).

Angular momentum in relativistic mechanics

In modern (20th century) theoretical physics, angular momentum is described using a different formalism. Under this formalism, angular momentum is the 2-form Noether charge associated with rotational invariance (As a result, angular momentum is not conserved for general curved spacetimes, unless it happens to be asymptotically rotationally invariant). For a system of point particles without any intrinsic angular momentum (see below), it turns out to be

(Here, the wedge product is used.).

In the language of four-vectors and tensors the angular momentum of a particle in relativistic mechanics is expressed as an antisymmetric tensor of second order

Angular momentum in quantum mechanics

Angular momentum in quantum mechanics differs in many profound respects from angular momentum in classical mechanics.

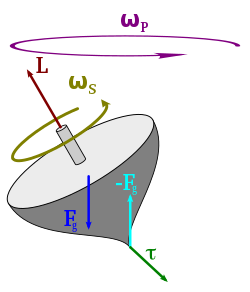

Spin, orbital, and total angular momentum

Left: "spin" angular momentum S is really orbital angular momentum of the object at every point,

right: extrinsic orbital angular momentum L about an axis,

top: the moment of inertia tensor I and angular velocity ω (L is not always parallel to ω),[4]

bottom: momentum p and it's radial position r from the axis.

The total angular momentum (spin plus orbital) is J. For a quantum particle the interpretations are different; particle spin does not have the above interpretation.The classical definition of angular momentum as can be carried over to quantum mechanics, by reinterpreting r as the quantum position operator and p as the quantum momentum operator. L is then an operator, specifically called the orbital angular momentum operator.

However, in quantum physics, there is another type of angular momentum, called spin angular momentum, represented by the spin operator S. Almost all elementary particles have spin. Spin is often depicted as a particle literally spinning around an axis, but this is a misleading and inaccurate picture: spin is an intrinsic property of a particle, fundamentally different from orbital angular momentum. All elementary particles have a characteristic spin, for example electrons always have "spin 1/2" (this actually means "spin ħ/2") while photons always have "spin 1" (this actually means "spin ħ").

Finally, there is total angular momentum J, which combines both the spin and orbital angular momentum of all particles and fields. (For one particle, J = L + S.) Conservation of angular momentum applies to J, but not to L or S; for example, the spin–orbit interaction allows angular momentum to transfer back and forth between L and S, with the total remaining constant.

Quantization

In quantum mechanics, angular momentum is quantized – that is, it cannot vary continuously, but only in "quantum leaps" between certain allowed values. For any system, the following restrictions on measurement results apply, where is the reduced Planck constant and is any direction vector such as x, y, or z:

| If you measure... | The result can be... |

| or | |

| () |

, where |

| or | , where |

(There are additional restrictions as well, see angular momentum operator for details.)

The reduced Planck constant is tiny by everyday standards, about 10−34 J s, and therefore this quantization does not noticeably affect the angular momentum of macroscopic objects. However, it is very important in the microscopic world. For example, the structure of electron shells and subshells in chemistry is significantly affected by the quantization of angular momentum.

Quantization of angular momentum was first postulated by Niels Bohr in his Bohr model of the atom.

Uncertainty

In the definition , six operators are involved: The position operators , , , and the momentum operators , , . However, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle tells us that it is not possible for all six of these quantities to be known simultaneously with arbitrary precision. Therefore, there are limits to what can be known or measured about a particle's angular momentum. It turns out that the best that one can do is to simultaneously measure both the angular momentum vector's magnitude and its component along one axis.

The uncertainty is closely related to the fact that different components of an angular momentum operator do not commute, for example . (For the precise commutation relations, see angular momentum operator.)

Total angular momentum as generator of rotations

As mentioned above, orbital angular momentum L is defined as in classical mechanics: , but total angular momentum J is defined in a different, more basic way: J is defined as the "generator of rotations".[5] More specifically, J is defined so that the operator

is the rotation operator that takes any system and rotates it by angle about the axis .

The relationship between the angular momentum operator and the rotation operators is the same as the relationship between lie algebras and lie groups in mathematics. The close relationship between angular momentum and rotations is reflected in Noether's theorem that proves that angular momentum is conserved whenever the laws of physics are rotationally invariant.

Angular momentum in electrodynamics

When describing the motion of a charged particle in an electromagnetic field, the canonical momentum P (derived from the Lagrangian for this system) is not gauge invariant. As a consequence, the canonical angular momentum L = r × p is not gauge invariant either. Instead, the momentum that is physical, the so-called kinetic momentum (used throughout this article), is (in SI units)

where e is the electric charge of the particle and A the magnetic vector potential of the electromagnetic field. The gauge-invariant angular momentum, that is kinetic angular momentum, is given by

The interplay with quantum mechanics is discussed further in the article on canonical commutation relations.

See also

- Absolute angular momentum

- Angular momentum coupling

- Angular momentum of light

- Angular momentum operator

- Areal velocity

- Balancing machine

- Control moment gyroscope

- Falling cat problem

- Linear-rotational analogs

- List of moments of inertia

- Moment of inertia

- Noether's theorem

- Precession

- Relative angular momentum

- Rigid rotor

- Rotational energy

- Specific relative angular momentum

- Spin (physics)

- Yrast

Footnotes

- ^ Truesdell, Clifford (1991). A First Course in Rational Continuum Mechanics: General concepts. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-701300-8.

- ^ Smith, Donald Ray; Truesdell, Clifford (1993). An introduction to continuum mechanics -after Truesdell and Noll. Springer. ISBN 0-7923-2454-4.

- ^ Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1995). The classical theory of fields. Course of Theoretical Physics. Oxford, Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-2768-9.

- ^ R.P. Feynman, R.B. Leighton, M. Sands (1964). Feynman's Lectures on Physics (volume 2). Addison-Wesley. pp. 31–7. ISBN 9-780-201-021172.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Littlejohn, Robert (2011). "Lecture notes on rotations in quantum mechanics" (PDF). Physics 221B Spring 2011. Retrieved 13 Jan 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work=

References

- Cohen-Tannoudji, Claude; Diu, Bernard; Laloë, Franck (2006). Quantum Mechanics (2 volume set ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-56952-7.

- Condon, E. U.; Shortley, G. H. (1935). "Especially Chapter 3". The Theory of Atomic Spectra. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09209-4.

- Edmonds, A. R. (1957). Angular Momentum in Quantum Mechanics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-07912-9.

- Jackson, John David (1998). Classical Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-30932-1.

- Serway, Raymond A.; Jewett, John W. (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers (6th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-40842-7.

- Thompson, William J. (1994). Angular Momentum: An Illustrated Guide to Rotational Symmetries for Physical Systems. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-55264-X.

- Tipler, Paul (2004). Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Mechanics, Oscillations and Waves, Thermodynamics (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0809-4.

External links

- Conservation of Angular Momentum - a chapter from an online textbook

- Angular Momentum in a Collision Process - derivation of the three dimensional case