Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde | |

|---|---|

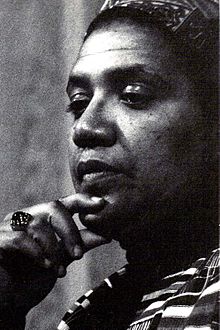

Audre Lorde, Austin, Texas, 1980 | |

| Born | February 18, 1934 New York City, New York |

| Died | November 17, 1992 (aged 58) St. Croix |

| Occupation | Poet, writer, activist, essayist |

| Genre | Poetry non-fiction |

Audre Lorde (born Audrey Geraldine Lorde February 18, 1934 – November 17, 1992) was a Caribbean-American writer and activist.

Life and work

Lorde was born in New York City to Caribbean immigrants from Barbados and Carriacou, Frederick Byron Lorde (called Byron) and Linda Gertrude Belmar Lorde, who settled in Harlem. Lorde's mother was of mixed ancestry but could pass for white, a source of pride for her family. Lorde's father was darker than the Belmar family liked and only allowed the couple to marry because of Byron Lorde's charm, ambition, and persistence.[1] Nearsighted to the point of being legally blind, and the youngest of three daughters (her sisters being named Phyllis and Helen), Lorde grew up hearing her mother's stories about the West Indies. She learned to talk while she learned to read, at the age of four, and her mother taught her to write at around the same time. She wrote her first poem when she was in eighth grade.

Born Audrey Geraldine Lorde, she chose to drop the "y" from her name while still a child, explaining in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, that she was more interested in the artistic symmetry of the "e"-endings in the two side-by-side names "Audre Lorde" than in spelling her name the way her parents had intended.[2] [3]

After graduating from Hunter College High School and experiencing the grief of her best friend Genevieve "Gennie" Thompson's death, Lorde immediately left her parents' home and became estranged from her family. She attended Hunter College from 1954 to 1959 and graduated with a bachelor's degree. While studying library science, Lorde supported herself by working various odd jobs such as factory worker, ghost writer, social worker, X-ray technician, medical clerk, and arts and crafts supervisor, moving out of Harlem to Stamford, Connecticut and beginning to explore her lesbian sexuality.[citation needed]

In 1954, she spent a pivotal year as a student at the National University of Mexico, a period she described as a time of affirmation and renewal: she confirmed her identity on personal and artistic levels as a lesbian and poet. On her return to New York, she attended college, worked as a librarian, continued writing and became an active participant in the gay culture of Greenwich Village. She furthered her education at Columbia University, earning a master's degree in library science in 1961. She also worked during this time as a librarian at Mount Vernon Public Library and married attorney Edwin Rollins; they divorced in 1970 after having two children, Elizabeth and Jonathan. In 1966, Lorde became head librarian at Town School Library in New York City, where she remained until 1968.[citation needed]

In 1968 Lorde was writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi,[4] where she met Frances Clayton, a white professor of psychology, who was to be her romantic partner until 1989. From 1977 to 1978 Lorde had a brief affair with the sculptor and painter Mildred Thompson. The two met in Nigeria in 1977 at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC 77). Their affair ran its course during the time that Thompson lived in Washington, D.C.[1] and was teaching at Howard University.[5] Lorde died on November 17, 1992, in St. Croix (where she had been living with Gloria I. Joseph), of liver cancer, though she dealt with a 14-year struggle with breast cancer. She was 58. In her own words, Lorde was a "black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet". In an African naming ceremony before her death, she took the name Gambda Adisa, which means "Warrior: She Who Makes Her Meaning Known".[6]

Last years

Audre Lorde battled cancer for fourteen years. She was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and underwent a mastectomy. Six years later, Lorde was diagnosed with liver cancer, from which she later died. As a result of her cancer, she chose to become more focused on both her life and her writing. She wrote The Cancer Journals which in 1981 won the American Library Association Gay Caucus Book of the Year Award.[7] She featured as the subject of a documentary called A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde that shows Lorde as an author, poet, human rights activist, feminist, and lesbian.[8] She is quoted in the film: "What I leave behind has a life of its own." "I've said this about poetry; I've said it about children. Well, in a sense I'm saying it about the very artifact of who I have been."[9]

From 1991 until her death in 1992, she was the New York State Poet Laureate.[10]

Work

Lorde's poetry was published very regularly during the 1960s — in Langston Hughes' 1962 New Negro Poets, USA; in several foreign anthologies; and in black literary magazines. During this time, she was politically active in civil rights, anti-war, and feminist movements. Her first volume of poetry, The First Cities (1968), was published by the Poet's Press and edited by Diane di Prima, a former classmate and friend from Hunter College High School. Dudley Randall, a poet and critic, asserted in his review of the book that Lorde "does not wave a black flag, but her blackness is there, implicit, in the bone." [citation needed]

Her second volume, Cables to Rage (1970), which was mainly written during her tenure at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, addressed themes of love, betrayal, childbirth and the complexities of raising children. It is particularly noteworthy for the poem "Martha", in which Lorde poetically confirms her homosexuality: "[W]e shall love each other here if ever at all." Later books continued her political aims in lesbian and gay rights, and feminism. In 1980, together with Barbara Smith and Cherríe Moraga, she co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, the first U.S. publisher for women of colour. Lorde was State Poet of New York from 1991 to 1992.[11]

Poetry

Lorde focused her discussion of difference not only on differences between groups of women but between conflicting differences within the individual. "I am defined as other in every group I'm part of", she declared. "The outsider, both strength and weakness. Yet without community there is certainly no liberation, no future, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between me and my oppression."[12] She described herself both as a part of a "continuum of women"[13] and a "concert of voices" within herself.[14]

Her conception of her many layers of selfhood is replicated in the multi-genres of her work. Critic Carmen Birkle wrote: "Her multicultural self is thus reflected in a multicultural text, in multi-genres, in which the individual cultures are no longer separate and autonomous entities but melt into a larger whole without losing their individual importance".[15] Her refusal to be placed in a particular category, whether social or literary, was characteristic of her determination to come across as an individual rather than a stereotype.

Theory

Lorde criticised feminists of the 1960s, from the National Organization for Women to Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique, for focusing on the particular experiences and values of white middle-class women.[citation needed] Her writings are based on the "theory of difference", the idea that the binary opposition between men and women is overly simplistic: although feminists have found it necessary to present the illusion of a solid, unified whole, the category of women itself is full of subdivisions.[16]

Lorde identified issues of class, race, age, gender and even health, this last was added as she battled cancer in her later years, as being fundamental to the female experience. She argued that, although the gender difference has received all the focus, these other differences are also essential and must be recognised and addressed. "Lorde", it is written, "puts her emphasis on the authenticity of experience. She wants her difference acknowledged but not judged; she does not want to be subsumed into the one general category of 'woman'".[17] This theory is today known as intersectionality.

While acknowledging that the differences between women are wide and varied, most of Lorde's works are concerned with two subsets that concerned her primarily — race and sexuality. In Ada Gay Griffin and Michelle Parkerson’s documentary A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, Lorde says, "Let me tell you first about what it was like being a Black woman poet in the ‘60s, from jump. It meant being invisible. It meant being really invisible. It meant being doubly invisible as a Black feminist woman and it meant being triply invisible as a Black lesbian and feminist.".[18] Lorde observes that black women's experiences are different from those of white women, and that, because the experience of the white woman is considered normative, the black woman's experiences are marginalised; similarly, the experiences of the lesbian (and, in particular, the black lesbian) are considered aberrational, not in keeping with the true heart of the feminist movement. Although they are not considered normative, Lorde argues that these experiences are nevertheless valid and feminist. [citation needed]

Contemporary feminist thought

Lorde set out to confront issues of racism in feminist thought. She maintained that a great deal of the scholarship of white feminists served to augment the oppression of black women, a conviction that led to angry confrontation, most notably in a scathing open letter addressed to the fellow radical lesbian feminist Mary Daly, to which Lorde stated she received no reply.[19] Daly's reply letter to Lorde,[20] dated 4½ months later, was found in 2003 in Lorde's files after she died.[21]

This fervent disagreement with notable white feminists furthered her persona as an "outsider": "in the institutional milieu of black feminist and black lesbian feminist scholars [...] and within the context of conferences sponsored by white feminist academics, Lorde stood out as an angry, accusatory, isolated black feminist lesbian voice".[22]

The criticism did not go only one way: many white feminists were angered by Lorde's brand of feminism. In her essay "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House",[23] Lorde attacked underlying racism within feminism, describing it as unrecognized dependence on the patriarchy. She argued that, by denying difference in the category of women, white feminists merely passed on old systems of oppression and that, in so doing, they were preventing any real, lasting change. Her argument aligned white feminists with white male slave-masters, describing both as "agents of oppression".[24]

In so doing, she enraged a great many white feminists, who saw her essay as an attempt to privilege her identities as black and lesbian, and assume a moral authority based on suffering.[citation needed] Suffering was a condition universal to women, they claimed, and to accuse feminists of racism would cause divisiveness rather than heal it.[citation needed] In response, Lorde wrote "what you hear in my voice is fury, not suffering. Anger, not moral authority."[25]

Works

- The First Cities (1968).

- Cables to Rage (1970)

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - From a Land Where Other People Live (1973)

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - New York Head Shop and Museum (1974)

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - Coal (1976). ISBN 0-393-04439-4. OCLC 2074270.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Between Our Selves (1976)

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - The Black Unicorn (1978, W.W. Norton Publishing). ISBN 0-393-04508-0. OCLC 3966122.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - The Cancer Journals (1980 Aunt Lute Books)

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help)

Kore Press

- Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power (1981 Kore Books)Uses of the Erotic. ISBN 978-1-888553-10-9.

- Chosen Poems: Old and New (1982). ISBN 0-393-01576-9. OCLC 8114592.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1983, The Crossing Press

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help)) - Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (1984, 2007, The Crossing Press)

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - Our Dead Behind Us (1986). ISBN 0-393-02329-X. OCLC 13870929.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - A Burst of Light (1988, Firebrand Books). ISBN 0-932379-40-0. OCLC 17619136.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - The Marvelous Arithmetics of Distance (1993). ISBN 0-393-31170-8. OCLC 38009170.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Interviews

- "Interview with Audre Lorde," in Against Sadomasochism: A Radical Feminist Analysis, ed. Robin Ruth Linden (East Palo Alto, Calif. : Frog in the Well, 1982.), pp. 66–71 . ISBN 0-960-36283-5. OCLC 7877113.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

See also

- African-American literature

- Audre Lorde Project, an organization in New York City named for Lorde

- Black Feminism

- Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, an organization in New York City named for Michael Callen and Lorde

- Womanism

Notes

- ^ a b De Veaux, Alexis (2004). A Biography of Audre Lorde. W.W. Norton & Co. pp. 7–13. ISBN 978-0-393-32935-3. Cite error: The named reference "de_Veaux" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Parks, Rev. Gabriele (August 3, 2008). "Audre Lorde". Thomas Paine Unitarian Universalist Fellowship. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ Lorde, Audre (1982). Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. Crossing Press.

- ^ "Audre Lorde". Poets.org. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ Thompson, Mildred (Spring 1987). "Memoirs of an Artist". SAGE: A Scholarly Journal on Black Women. IV (1): 41–44.

- ^ Audre Lorde biodata - life and death

- ^ [1]

- ^ "A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde (1995)". The New York Times.

- ^ "A Litany For Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde". POV. PBS. June 18, 1996.

- ^ "New York". US State Poet Laureates. Library of Congress. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ^ "Audre Lorde 1934–1992". Enotes.com. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- ^ The Cancer Journals, pp. 12–13.

- ^ The Cancer Journals, p. 17.

- ^ The Cancer Journals, p. 31.

- ^ Birkle, p. 180.

- ^ Olson, Lester C.; "Liabilities of Language: Audre Lorde Reclaiming Difference."

- ^ Birkle, p. 202.

- ^ Griffin, Ada Gay; Michelle Parkerson. "Audre Lorde", BOMB Magazine Summer 1996. Retrieved 19 January 2012

- ^ Lorde, Audre (1984). Sister Outsider. Berkeley: Crossing Press. p. 66. ISBN 1-58091-186-2.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Amazon Grace (N.Y.: Palgrave Macmillan, 1st ed. [1st printing?] Jan. 2006), pp. 25–26 (reply text).

- ^ Amazon Grace, supra, pp. 22–26, esp. pp. 24–26 & nn. 15–16, citing Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde, by Alexis De Veaux (N.Y.: W.W. Norton, 1st ed. 2004) (ISBN 0393019543 or ISBN 0-393-32935-6).

- ^ De Veaux, p. 247.

- ^ Sister Outsider, pp. 110–114.

- ^ De Veaux, p. 249.

- ^ Sister Outsider, p. 132.

References

- Birkle, Carmen. Women's Stories of the Looking Glass. Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1996. . ISBN 3-7705-3083-7. OCLC 34821525.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Byrd, Rudolph; Cole, Johnnetta Betsch; Guy-Sheftall, Beverly. I Am Your Sister: Collected and Unpublished Writings of Audre Lorde New York: Oxford University University Press, 2009. . ISBN 978-0-19-534148-5.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - De Veaux, Alexis. Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde. New York and London: W.W. Norton, 2004. . ISBN 0-393-01954-3. OCLC 53315369.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Hall, Joan Wylie. Conversations with Audre Lorde. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2004. . ISBN 1-57806-642-5. OCLC 55762793.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Keating, AnaLouise (1996). Women Reading Women Writing: Self-Invention in Paula Gunn Allen, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Audre Lorde. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press. ISBN 1-56639-419-8. OCLC 33160820.

Biographical film

- A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde (1995) Documentary by Michelle Parkeson.

- The Edge of Each Other's Battles: The Vision of Audre Lorde (2002). Documentary by Jennifer Abod.

- Audre Lorde - The Berlin Years 1984 to 1992 (2012). Documentary by Dagmar Schultz.

External links

Profile

- Profile and poems at the Poetry Foundation

- Profile and poems written and audio at Academy of American Poets

- "Voices From the Gaps: Audre Lorde". Profile. University of Minnesota

- Profile at Modern American Poetry

Articles and archive

- 1934 births

- 1992 deaths

- Audre Lorde

- African-American novelists

- African-American women writers

- African-American writers

- American activists

- American librarians

- American people of Barbadian descent

- American people of Carriacouan descent

- American people of United States Virgin Islands descent

- American poets

- African-American librarians

- Black feminists

- Cancer deaths in the United States Virgin Islands

- Columbia University alumni

- Deaths from breast cancer

- Hunter College alumni

- Hunter College High School alumni

- Feminist critics of BDSM

- Feminist studies scholars

- Feminist writers

- Lambda Literary Award winners

- Lesbian writers

- Lesbian African Americans

- LGBT rights activists from the United States

- LGBT writers from the United States

- Poets Laureate of New York

- Radical lesbian feminists