Bernard Moitessier

Bernard Moitessier (10 April 1925 – 16 June 1994) was a renowned French yachtsman and author of books about his voyages and sailing.

In 1968 Moitessier participated in the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race, which would reward the first sailor as well as the fastest sailor to circumnavigate the Earth solo, non-stop. Although Moitessier stood a very good chance of winning, he abandoned his effort seven months into the race, and continued on to Tahiti rather than returning to England.

Vagabond of the South Seas

Moitessier grew up next to the sea in Indo-China and left it at the beginning of the Vietnam War as a crew member of sailing trade junks. In Indonesia he purchased the dilapidated junk Marie-Thérèse in 1952 to travel slowly further to France by singlehanded sailing. On the first leg to Seychelles he had to stop her from leaking in the middle of the Indian Ocean by diving underneath the boat at sea.[1] After 85 days of sailing through monsoon weather he ran aground on Diego Garcia, due to not having modern navigational instruments. He was deported to Mauritius, because Diego Garcia is a military restricted area, and worked there three years before he could sail again in a boat he had built himself. This he sailed via stops in South Africa and St. Helena to the West Indies, but on a trip from Trinidad to St. Lucia he once again was shipwrecked due to physical exhaustion. Picked up and taken back to Trinidad by friends, he decided to go to France directly, as it seemed the only place he could earn enough to build himself a worthy boat. He was able to get work on a cargo ship which got him to France, via Hamburg, where he found work with a medical company whilst writing a book about his experience (Vagabond des Mers du Sud). He then moved to the south of France, where he married Francoise, the daughter of family friends, with whom he was to sail the world.

With the money from his book, he commissioned a 39' steel ketch which he named Joshua, in honour of Joshua Slocum, the first person to sail around the world solo. Finally he and Francoise left Marseille in October 1963, leaving her three children in boarding schools. After wintering in Casablanca they sailed first to the Canaries, then to Trinidad, and through the Panama Canal to the Galapagos Islands. After two years of spending time in each of these places they arrived at Tahiti, but realised that they were running out of time and that there was just eight months left to return to their children. So Moitessier proposed sailing Joshua home not via the Indian Ocean and Suez Canal, as originally planned, but eastwise, via the quickest route, including a passage about the much feared Cape Horn. Upon their arrival in France, at Easter, 1966, they had, without intending it, completed the longest nonstop passage by a yacht in history—14216 nautical miles, over 126 days, a world record which brought him immediate recognition throughout the world yachting community.[2]

Solo around the world

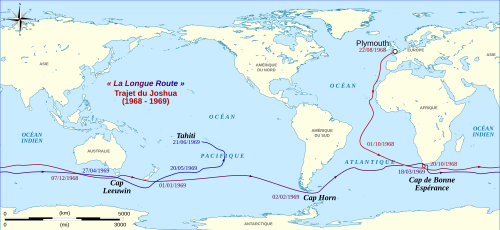

Discussions between Moitessier and his friends Bill King and Loïck Fougeron about a solo non-stop trip around the world came to the notice of Robin Knox-Johnston who also started preparations before the Sunday Times offered their Golden Globe award for the first to circumnavigate alone, nonstop, and unassisted, and for the fastest elapsed time. Somewhat reluctantly, Moitessier decided to sail Joshua to Plymouth to meet the criterion for the race of leaving from an English port, but left months after several smaller and therefore slower boats.

He departed Plymouth on 23 August 1968 and, after a quick passage south, he was off the Cape of Good Hope by 20 October 1968. In the process of transferring a canister of film and reports for the Sunday Times to a freighter, he allowed the bow of Joshua to be drawn into the stern of the ship, bending the bowsprit, which he was able to fix with winches on board.[3] A couple of days later Joshua was knocked flat by a breaking wave but he was able to recover the damage. A succession of gales and calm periods characterised his trip through the Southern Ocean till he passed Cape Horn on 5 Feb 1969. In all this time he got no feedback on the progress of other competitors from local radio stations.

From the time of calms in the Indian Ocean where he was depressed and discovered yoga as a means of controlling his moods, he started to think of not returning to Europe which he saw as a cause of many of his worries. The aim of continuing his voyage on again to the Galapagos Islands strengthened as he passed through the Pacific though he was determined to complete the circumnavigation first. Finally having passed Cape Horn he had a crisis when a south-easterly gale started blowing him north again, and his account of his thought processes before he turned for the Cape of Good Hope reflects inner turmoil. However, the manner of his resignation, as he tells the story, is a key part of his reputation. Communicating with his London Times correspondent via firing by catapult a message onto the deck of a passing ship, he said: "...parce que je suis heureux en mer et peut-etre pour sauver mon ame" ("...because I am happy at sea and perhaps to save my soul").[4]

The decision to abandon is instructive of Moitessier's character – although driven and competitive, he passed up a chance at instant fame and a record, and sailed on for three more months. Sir Robin Knox-Johnston went on both to win the race—as the only legitimate finisher—and to become the first man to circumnavigate the globe alone without stopping.

Although he abandoned the race, Moitessier still circumnavigated the world, crossing his path off South Africa, and then by sailing almost two-thirds of the way round a second time, all non-stop and mostly in the roaring forties, set another record for the longest nonstop passage by a yacht, with a total of 37,455 nautical miles in 10 months. Despite heavy weather and a couple of severe knockdowns, he even contemplated rounding the Horn again. However, he decided that he and Joshua had had enough and, on 21 June 1969, put in at Tahiti, from where he and his wife had set out for Alicante, Spain, a decade earlier. He thus had completed his second personal circumnavigation of the world (including the previous voyage with his wife).

It is impossible to say that Moitessier would have won if he had completed the race, as he would have been sailing in different weather conditions than Knox-Johnston; based on his time from the start to Cape Horn being about 77% of that of Knox-Johnston, it would have been an extremely close race. His book of the experience, The Long Way, tells the story of his voyage as a spiritual journey as much as a sailing adventure and is still regarded as a classic of sailing and adventuring literature.

Subsequent life, and grave

It took him two years to finish the book about his trip in Tahiti, during which time he met Ileana Draghici with whom he had a son, Stephan. They moved to the atoll of Ahe, where Moitessier attempted to cultivate fruit and vegetables. Ileana encouraged him to move to America to complete films about his sailing but he left after two years in his boat Joshua.

Joshua was beached, along with many other yachts, by Hurricane Paul at Cabo San Lucas in 1982. It was salvaged and restored, and is today berthed as part of a maritime museum in La Rochelle, France. After further travels, Moitessier returned to Paris to write his autobiography.

Moitessier was an environmental activist who protested against nuclear weapons in the South Pacific and against overdevelopment of the Papeete waterfront in Tahiti. He died of cancer on 16 June 1994 and is buried in an informal corner of the formal main cemetery in Bono, in Brittany, France. Visitors to his grave leave thematic gifts such as catapults, creating some elements of a shrine.

Partial list of works

- Un Vagabond des mers du sud 1960. Translated by Rene Hague as Sailing to the Reefs.

- Cap Horn à la voile: 14216 milles sans escale 1967. Translated by Inge Moore as Cape Horn: The Logical Route.

- La Longue route; seul entre mers et ciels 1971. Translated as The Long Way by William Rodarmor, 1973.

- Tamata et l'alliance 1993. Translated as Tamata and the Alliance by William Rodarmor, 1995.

- Voile, Mers Lointaines, Iles et Lagons 1995. Translated as A Sea Vagabond's World by William Rodarmor, 1998.

Quotes

"You do not ask a tame seagull why it needs to disappear from time to time toward the open sea. It goes, that's all."

"Man is always the strongest." (--after having to bend his steel bowsprit back, after collision, alone and unassisted during the Golden Globe race.)

"I am a citizen of the most beautiful nation on earth. A nation whose laws are harsh yet simple, a nation that never cheats, which is immense and without borders, where life is lived in the present. In this limitless nation, this nation of wind, light, and peace, there is no other ruler besides the sea."

"I no longer know how far I have got, except that we long ago left the borders of too much behind." (--just before passing Cape Horn for the second time.)

"I wonder. Plymouth so close, barely 10,000 miles to the north...but leaving from Plymouth and returning to Plymouth now seems like leaving from nowhere to go nowhere." (--after rounding the Horn in the Golden Globe race.)

"My real log is written in the sea and sky; the sails talking with the rain and the stars amid the sounds of the sea, the silences full of secret things between my boat and me, like the times I spent as a child listening to the forest talk." (--from "The Long Way")

"The geography of the sailor is not always the one of the cartographer, for whom a cape is a cape with its longitude and latitude. For the sailor, a great cape is both very simple and extremely complex, with rocks, currents, furling seas, beautiful oceans, good winds and gusts, moments of happiness and of fright, fatigue, dreams, aching hands, an empty stomach, marvelous minutes and sometimes suffering. A great cape, for us, cannot be translated only into a latitude and a longitude. A great cape has a soul, with shadows and colors, very soft, very violent. A soul as smooth as that of a child, as hard as that of a criminal." (--from "The Long Way")

Notes

- ^ Bernard Moitessier, trans. Inge Moore (1969). Cape Horn: The Logical Route. Adlard Coles Nautical.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|note=ignored (help) - ^ Peter Nichols (2002). A Voyage For Madmen. Perennial, US.

- ^ Peter Nichols (2002). A Voyage For Madmen. Perennial, US.

- ^ Bernard Moitessier, trans. William Rodarmor (1974). The Long Way. Adlard Coles Nautical, UK.