List of lay Catholic scientists

Thousands of Catholics, both clerics and laypersons alike, have made significant contributions to the development of science and mathematics from the Middle Ages to today. These scientists include Galileo Galilei, Rene Descartes, Nicolas Copernicus, Louis Pasteur, Blaise Pascal, André-Marie Ampère, Gregor Mendel, Charles-Augustin de Coulomb, Pierre de Fermat, Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, Marin Mersenne, Alessandro Volta, Augustin-Louis Cauchy, Pierre Duhem, Jean-Baptiste Dumas, Roger Boscovich, Pierre Gassendi, and Georgius Agricola, to name a few.

Catholic scientists are considered the fathers of numerous scientific fields, including, but not limited to, modern physics, acoustics, mineralogy, modern chemistry, modern anatomy, stratigraphy, bacteriology, genetics, analytical geometry, and heliocentric cosmology.[1] Inventions from Catholic scientists include the battery, the barometer, the stethoscope, the mechanical calculator, braille, mechanical movable type printing, and the Foucault pendulum. Three electrical units are named after Catholic scientists as well: the amp, the volt, and the coulomb.

The Catholic Church has supported scientific research since the emergence of the European universities in the Middle Ages. Historian Lawrence M. Principe writes that "it is clear from the historical record that the Catholic church has been probably the largest single and longest-term patron of science in history, that many contributors to the Scientific Revolution were themselves Catholic, and that several Catholic institutions and perspectives were key influences upon the rise of modern science."[2] The field of astronomy is a prime example of the Church's commitment to science. J.L. Heilbron in his book The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as Solar Observatories writes that "The Roman Catholic Church gave more financial aid and support to the study of astronomy for over six centuries, from the recovery of ancient learning during the late Middle Ages into the Enlightenment, than any other, and, probably, all other, institutions."[3]

Scientific support continues through the present day. The Pontifical Academy of Sciences was founded in 1936 by Pope Pius XI, with the aim of promoting the progress of the mathematical, physical and natural sciences and the study of related epistemological problems. The academy holds a membership roster of the most respected names in 20th century science, many of them Nobel laureates. Also worth noting is the Vatican Observatory, which is an astronomical research and educational institution supported by the Holy See.

In his 1996 encyclical Fides et Ratio Pope John Paul II wrote that "Faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth."[4] Pope Benedict XVI re-emphasized the importance of reason in his famous 2006 address at Regensburg.[5] But the emphasis on reason is not a recent development in the Church's history. In the first few centuries of the Church, the Church Fathers appropriated the best of Greek Philosophy in defense of the Faith. This appropriation culminated in the 13th century writings of Thomas Aquinas, whose synthesis of faith and reason has influenced Catholic thought for eight centuries. Because of this synthesis, it should be no surprise that many historians of science trace the foundations of modern science to the 13th century. These writers include Edward Grant,[6] James Hannam,[7] and Pierre Duhem,[8] to name a few.

Yet, the Galileo affair has come to typify the Church's relationship with science, although it was an exception rather than a rule. Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman has referred to the Galileo affair as the "one stock argument"[9] against the Church. The standard treatment of Galileo as a martyr for science has been overturned by modern historians, however. In fact, his theories were celebrated by popes and churchmen alike, with members of the Jesuits personally verifying many of his observations.[10] Galileo encountered trouble when he presented heliocentrism as fact rather than theory, when he lacked the necessary proofs to overturn long-standing science.

The scientific contributions made by Catholic scientists have been extensive.

Catholic scientists

- Maria Gaetana Agnesi (1718–1799) - Mathematician who wrote on differential and integral calculus

- Georgius Agricola (1494–1555) - Father of Mineralogy[11]

- Albertus Magnus (c.1206-1280) - Patron saint of natural sciences

- André-Marie Ampère (1775–1836) - One of the main discovers of electromagnetism

- Amedeo Avogadro (1776–1856) - Noted for contributions to molecular theory and Avogadro's Law

- Roger Bacon (c. 1214-1294) - Franciscan friar and early advocate of the scientific method

- Daniello Bartoli (1608-1685) - Jesuit priest and one of the first to see the equatorial belts of Jupiter

- Antoine César Becquerel (1788-1878) - Pioneer in the study of electric and luminescent phenomena

- Henri Becquerel (1852–1908) - Awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for his co-discovery of radioactivity

- John Desmond Bernal (1901–1971) - was one of the United Kingdom's most well-known and controversial scientists. Known as "Sage" to friends, Bernal is considered a pioneer in X-ray crystallography in molecular biology.[12][13]

- Claude Bernard (1813-1878) - Renowned physiologist who helped to apply scientific methodology to medicine

- Jacques Philippe Marie Binet (1786–1856) - Mathematician known for Binet's formula and his contributions to number theory

- Jean-Baptiste Biot (1774–1862) - Physicist who established the reality of meteorites and studied polarization of light

- Bernard Bolzano (1781-1848) - Priest and mathematician who made important contributions to differentiation, the concept of infinity, and the binomial theorem

- Giovanni Alfonso Borelli (1608-1679) - Often referred to as the father of modern biomechanics

- Roger Joseph Boscovich (1711–1787) - Jesuit priest and polymath known for his atomic theory and many other scientific contributions

- Raoul Bott (1923-2005) - mathematician known for numerous basic contributions to geometry in its broad sense.[14][15]

- Thomas Bradwardine (c.1290-1349) - Archbishop and one of the discovers of the mean speed theorem

- Louis Braille (1809–1852) - Inventor of the Braille reading and writing system

- Martin Stanislaus Brennan (1845-1927) - Priest and astronomer who wrote several books about science

- Jean Buridan (c.1300-after 1358) - French priest who developed the theory of impetus

- Alexis Carrel (1873–1944) - Awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for pioneering vascular suturing techniques

- John Casey (mathematician) (1820-1891) - Irish geometer known for Casey's theorem

- Giovanni Domenico Cassini (1625–1712) - First to observe four of Saturn's moons and the co-discoverer of the Great Red Spot on Jupiter

- Augustin-Louis Cauchy (1789–1857) - Mathematician who was an early pioneer in analysis

- Bonaventura Cavalieri (1598-1647) - Churchman known for his work on the problems of optics and motion, work on the precursors of infinitesimal calculus, and the introduction of logarithms to Italy. Cavalieri's principle in geometry partially anticipated integral calculus.

- Andrea Cesalpino (c.1525-1603) - Botanist who also theorized on the circulation of blood

- Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) - Published the first translation of the Rosetta Stone

- Guy de Chauliac (c.1300-1368) - The most eminent surgeon of the Middle Ages

- Albert Claude (1899-1983) - Awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his contributions to the study of cells

- Christopher Clavius (1538–1612) - Jesuit who was the main architect of the Gregorian calendar

- Mateo Realdo Colombo (1516–1559) - Discovered the pulmonary circuit,[16] which paved the way for Harvey's discovery of circulation

- Carl Ferdinand Cori (1896-1984) - Shared the Nobel Prize with his wife for their discovery of the Cori cycle

- Gerty Cori (1896-1957) - First American woman win a Nobel Prize in science, and the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[17]

- Gaspard-Gustave Coriolis (1792-1843) - Formulated laws regarding rotating systems, which later became known as the Corialis effect

- Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (1736–1806) - Physicist known for developing Coulomb's law

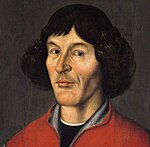

- Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) - First person to formulate a comprehensive heliocentric cosmology

- Johann Baptist Cysat (c.1587-1657) - Jesuit priest known for his study of comets

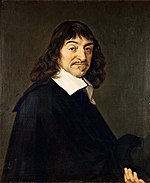

- René Descartes (1596–1650) - Father of modern philosophy and analytic geometry

- Pierre Duhem (1861–1916) - Historian of science who made important contributions to hydrodynamics, elasticity, and thermodynamics

- Jean-Baptiste Dumas (1800–1884) - Chemist who established new values for the atomic mass of thirty elements

- Christian de Duve (1917–present) - Nobel Prize winning cytologist and biochemist

- John Eccles (neurophysiologist) (1903–1997) - Awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work on the synapse

- Stephan Endlicher (1804-1849) - Botanist who formulated a major system of plant classification

- Bartolomeo Eustachi (c.1500-1574) - One of the founders of human anatomy

- Hieronymus Fabricius (1537–1619) - Father of embryology

- Gabriele Falloppio (1523–1562) - One of the most important anatomists and physicians of the sixteenth century

- Mary Celine Fasenmyer (1906-1996) - Roman Catholic sister and mathematician, founder of Sister Celine's polynomials

- Pierre de Fermat (1601–1665) - Number theorist who contributed to the early development of calculus

- Enrico Fermi (1901–1954) - Awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for his work in induced radioactivity

- Fibonacci (c.1170-c.1250) - Popularized Hindu-Arabic numerals in Europe and discovered the Fibonacci sequence

- Hippolyte Fizeau (1819-1896) - The first person to determine experimentally the velocity of light[18]

- Léon Foucault (1819–1868) - Invented the Foucault pendulum to measure the effect of the earth's rotation

- Joseph von Fraunhofer (1787–1826) - Discovered Fraunhofer lines in the sun's spectrum

- Augustin-Jean Fresnel (1788–1827) - Made significant contributions to the theory of wave optics

- Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) - Father of modern science

- Luigi Galvani (1737–1798) - Formulated the theory of animal electricity

- Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655) - French astronomer and mathematician who published the first data on the transit of Mercury and gave the Aurora Borealis its name

- Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778-1850) - Chemist known for two laws related to gases

- Riccardo Giacconi (1913- ) - Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist who laid the foundations of X-ray astronomy

- Paula González (1932-present) - Roman Catholic sister and professor of biology

- Francesco Maria Grimaldi (1618–1663) - Jesuit who discovered the diffraction of light

- Robert Grosseteste (c.1175-1253) - Bishop who has been called "the first man to write down a complete set of steps for performing a scientific experiment."[19]

- Peter Grünberg (1939- ) - German physicist, and Nobel Prize in Physics laureate.[20]

- Johannes Gutenberg (c.1398-1468) - Inventor of the printing press

- Jean Baptiste Julien d'Omalius d'Halloy (1783–1875) - One of the pioneers of modern geology[21]

- John Harsanyi (1929-2000) - Hungarian-American economist and Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences winner.[22]

- René Just Haüy (1743–1822) - Priest, and father of crystallography

- Eduard Heis (1806-1877) - Astronomer who contributed the first true delineation of the Milky Way

- Jan Baptist van Helmont (1579-1644) - Founder of pneumatic chemistry

- George de Hevesy (1885 - 1966) - was a Hungarian radiochemist and Nobel laureate.[23]

- Charles Hermite (1822–1901) - Mathematician who did research on number theory, quadratic forms, elliptic functions, and algebra

- John Philip Holland (1840–1914) - Developed the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the U.S. Navy

- Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (1748-1836) - The first to propose a natural classification of flowering plants

- Athanasius Kircher (c.1601-1680) - Jesuit scholar who has been called "the last Renaissance man"

- Brian Kobilka (1955- ) - an American Nobel Prize winning professor in the departments of Molecular and Cellular Physiology at Stanford University School of Medicine.[24][25]

- Nicolas Louis de Lacaille (1713–1762) - French astronomer noted for cataloguing stars, nebulous objects, and constellations

- René Laennec (1781–1826) - Physician who invented the stethoscope

- Joseph Louis Lagrange (1736-1813) - Mathematician and astronomer known for Lagrangian points and Lagrangian mechanics

- Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) - Biologist whose theories on evolution preceded those of Darwin; also divided the animal kingdom into vertebrates and invertebrates

- Karl Landsteiner (1868–1943) - Nobel Prize winner who identified and classified the human blood types

- Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749–1827) - Famed mathematician and astronomer who has been called the "Newton of France"

- Pierre André Latreille (1762-1833) - Pioneer in entomology

- Antoine Lavoisier (1743–1794) - Father of modern chemistry[26]

- Jérôme Lejeune (1926-1994) - Pediatrician and geneticist, best known for his discovery of the link of diseases to chromosome abnormalities

- Georges Lemaître (1894–1966) - Father of the Big Bang theory

- Marcello Malpighi (1628–1694) - Father of comparative physiology[27]

- Étienne-Louis Malus (1775-1812) - Discovered the polarization of light

- Guglielmo Marconi (1874–1937) - Father of long-distance radio transmission

- Edme Mariotte (c.1620-1684) - Priest who independently discovered Boyle's Law

- Pierre Louis Maupertuis (1698-1759) - Known for the Maupertuis principle and for being the first president of the Berlin Academy of Science

- Gregor Mendel (1822–1884) - Father of genetics

- Marin Mersenne (1588–1648) - Father of acoustics and mathematician for whom Mersenne primes are named.

- Charles W. Misner (1932-present) - American cosmologist dedicated to the study of general relativity

- Gaspard Monge (1746-1818) - Father of descriptive geometry

- Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682–1771) - Father of modern anatomical pathology[28]

- Johannes Peter Müller (1801–1858) - Founder of modern physiology[29]

- Joseph Murray (1919-2012) - Nobel Prize in Medicine laureate.[30]

- Jean-Antoine Nollet (1700-1770) - Discovered the phenomenon of osmosis in natural membranes.

- William of Ockham (c.1288-c.1348) - Franciscan Friar known for Ockham's Razor

- Nicole Oresme (c.1320-1382) - 14th century bishop who theorized the daily rotation of the earth on its axis

- Barnaba Oriani (1752-1832) - Known for Oriani's theorem and for his research on Uranus

- Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598) - Created the first modern atlas and theorized on continental drift

- Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) - One of the most famous mathematicians of all time

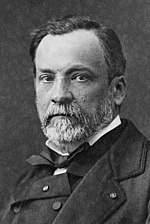

- Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) - Father of bacteriology[31]

- Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580–1637) - Discovered the Orion Nebula

- Georg von Peuerbach (1423–1461) - Has been called the father of mathematical and observational astronomy in the West[32]

- Giuseppe Piazzi (1746-1826) - Theatine priest who discovered the asteroid Ceres and did important work cataloguing stars

- Jean Picard (1620–1682) - French priest and father of modern astronomy in France[33]

- Vladimir Prelog (1906 - 1998) - Croatian-Swiss organic chemist, winner of the 1975 Nobel Prize for chemistry.

- Jules Henri Poincaré (1854 – 1912) - French mathematician, theoretical physicist, engineer, and a philosopher of science, who discovered a chaotic deterministic system which laid the foundations of modern chaos theory and was one of the founders of topology

- John Polanyi (1929 - ) - is a Canadian chemist who won the 1986 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for his research in chemical kinetics.[34]

- Michael Polanyi(1891 - 1976) - was a Hungarian polymath, who made important theoretical contributions to physical chemistry, economics, and philosophy.

- Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852-1934) - Awarded the Nobel Prize for his contributions to neuroscience

- René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur (1683-1757) - Scientific polymath known especially for his study of insects

- Francesco Redi (1626-1697) - His famous experiments with maggots were a major step in overturning the idea of spontaneous generation

- Henri Victor Regnault (1810-1878) - Chemist with two laws governing the specific heat of gases named after him[35]

- Giovanni Battista Riccioli (1598–1671) - Jesuit priest and the first person to measure the acceleration due to gravity of falling bodies

- Wilhelm Roentgen (1845-1923) - Discovered X-rays.

- Theodor Schwann (1810–1882) - Founder of the theory of the cellular structure of animal organisms

- Angelo Secchi (1818-1878) - Jesuit priest who developed the first system of stellar classification

- Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865) - Early pioneer of antiseptic procedures and the discoverer of the cause of puerperal fever

- Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729-1799) - Priest and biologist who laid the groundwork for Pasteur's discoveries

- Nicolas Steno (1638–1686) - Bishop, and father of stratigraphy

- Francesco Lana de Terzi (1631-1687) - Jesuit priest who has been called the father of aeronautics

- Louis Jacques Thénard (1777–1857) - Discovered hydrogen peroxide

- Theodoric of Freiberg (c.1250-c.1310) - Gave the first geometrical analysis of the rainbow

- Evangelista Torricelli (1608–1647) - Inventor of the barometer

- Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli (1397–1482) - One of the most distinguished scientists of the fifteenth century

- Richard Towneley (1629-1707) - Mathematician and astronomer whose investigations and correspondence contributed to the formulation of Boyle's Law

- Louis René Tulasne (1815-1885) - Noted biologist with several genera and species of fungi named after him

- Louis Nicolas Vauquelin (1763–1829) - Discovered the chemical element Beryllium

- Pierre Vernier (1580-1637) - Mathematician who invented the Vernier scale

- Urbain Le Verrier (1811–1877) - Mathematician who predicted the discovery of Neptune

- Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) - Father of modern human anatomy

- François Viète (1540–1603) - Father of Modern Algebra[36]

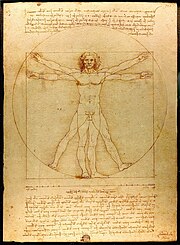

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) - Renaissance anatomist, scientist, mathematician, and painter

- Vincenzo Viviani (1622-1703) - Mathematician known for Viviani's theorem and Viviani's curve as well as his experiments to determine the speed of sound

- Alessandro Volta (1745–1827) - Physicist known for the invention of the battery

- Wilhelm Heinrich Waagen (1841–1900) - Geologist and paleontologist

- Karl Weierstrass (1815-1897) - Often called the Father of Modern Analysis[37]

- E. T. Whittaker (1873–1956) - English mathematician who made contributions to applied mathematics and mathematical physics

- Eric F. Wieschaus (1947- ) - He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

- Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) - One of the founders of scientific archaeology

See also

External links

References

- ^ Modern physics (Galileo), acoustics (Mersenne), mineralogy (Agricola), modern chemistry (Lavoisier), modern anatomy (Vesalius), stratigraphy (Steno), bacteriology (Pasteur), genetics (Mendel), analytical geometry (Descartes), and heliocentric cosmology (Copernicus).

- ^ Galileo Goes to Jail: And Other Myths about Science and Religion. Ed. Ronald L. Numbers. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009. (p. 102)

- ^ Heilbron, J.L. The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as Solar Observatories. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999. (p. 3)

- ^ Pope John Paul II. Fides Et Ratio. Boston: Pauline and Media, 1998. (Introductory matter)

- ^ The text of the address can be found here: Faith, Reason and the University Memories and Reflections

- ^ cf. Grant, Edward. The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- ^ cf. Hannam, James. The Genesis of Science: How the Christian Middle Ages Launched the Scientific Revolution. Washington, DC: Regnery Pub., 2011.

- ^ Duhem wrote a famous 10 volume work on science in the Middle Ages. He put particular emphasis on the Condemnations of Paris in 1277 as the origin of modern science.

- ^ Newman, John Henry. Apologia Pro Vita Sua. Ed. Ian T. Ker. London: Penguin, 1994. (p. 235)

- ^ Woods, Thomas E. How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization. Washington, DC: Regnery Pub., 2005. (p. 69)

- ^ George Agricola

- ^ Brown, Andrew (2005). J. D. Bernal: the sage of science. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-851544-8.

- ^ Brown 2005, pp. 1–3

- ^ http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/Biographies/Bott.html

- ^ http://www.ams.org/notices/200605/fea-bott-2.pdf

- ^ Mateo Realdo Colombo

- ^ http://www.csupomona.edu/~nova/scientists/articles/cori.html

- ^ Armand-Hippolyte-Louis Fizeau

- ^ Woods, Thomas E. How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization. Washington, DC: Regnery Pub., 2005. (p. 95-96)

- ^ "Peter Grünberg – Autobiography".

- ^ Jean-Baptiste-Julien D'Omalius Halloy

- ^ http://www.nap.edu/html/biomems/jharsanyi.pdf

- ^ Levi, Hilde (1985), George de Hevesy : life and work : a biography, Bristol: A. Hilger, p. 14, ISBN 9780852745557

- ^ http://www.catholicnews.com/data/briefs/cns/20121023.htm#head1

- ^ http://www.austindiocese.org/newsletter_article_view.php?id=7177

- ^ Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier

- ^ Marcello Malpighi

- ^ Giovanni Battista Morgagni

- ^ Johann Müller

- ^ http://www.adherents.com/people/pm/Joseph_Murray.html

- ^ Louis Pasteur

- ^ George von Peuerbach

- ^ Jean Picard

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1177/0048393105277986, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1177/0048393105277986instead. - ^ Henri Victor Regnault

- ^ François Vieta, Seigneur de La Bigottière

- ^ The Princeton Companion to Mathematics. Ed. Timothy Gowers. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008. (p.770).