Zircon

| Zircon | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Nesosilicates |

| Formula (repeating unit) | zirconium silicate ZrSiO4 |

| Strunz classification | 09.AD.30 |

| Crystal system | Tetragonal |

| Space group | Tetragonal ditetragonal dipyramidal H-M symbol: (4/m 2/m 2/m) Space group: I 41/amd |

| Unit cell | a = 6.607(1) Å, c = 5.982(1) Å; Z=4 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Reddish brown, yellow, green, blue, gray, colorless; in thin section, colorless to pale brown |

| Crystal habit | tabular to prismatic crystals, irregular grains, massive |

| Twinning | On {101} |

| Cleavage | indistinct, on {110} and {111} |

| Fracture | Conchoidal to uneven |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 7.5 |

| Luster | Vitreous to adamantine; greasy when metamict. |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to opaque |

| Specific gravity | 4.6–4.7 |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (+) |

| Refractive index | nω = 1.925–1.961 nε = 1.980–2.015, 1.75 when metamict |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.047–0.055 |

| Pleochroism | Weak |

| Fusibility | Infusible |

| Solubility | Insoluble |

| Other characteristics | Fluorescent and radioactive, may form pleochroic halos |

| References | [1][2][3][4] |

Zircon (/ˈzɜːrkən/; including hyacinth or yellow zircon) is a mineral belonging to the group of nesosilicates. Its chemical name is zirconium silicate and its corresponding chemical formula is ZrSiO4. A common empirical formula showing some of the range of substitution in zircon is (Zr1–y, REEy)(SiO4)1–x(OH)4x–y. Zircon forms in silicate melts with large proportions of high field strength incompatible elements. For example, hafnium is almost always present in quantities ranging from 1 to 4%. The crystal structure of zircon is tetragonal crystal system. The natural color of zircon varies between colorless, yellow-golden, red, brown, blue, and green. Colorless specimens that show gem quality are a popular substitute for diamond and are also known as "Matura diamond".

The name derives either from the Syriac word ܙܐܪܓܥܢܐ zargono,[5] from the Arabic word zarqun (زرقون), meaning vermilion, or from the Persian zargun (زرگون), meaning golden-colored.[6] These words are corrupted into "jargoon", a term applied to light-colored zircons. The English word "zircon" is derived from "Zirkon," which is the German adaptation of these words.[7] Red zircon is called "hyacinth", from the flower hyacinthus, whose name is of Ancient Greek origin.

Properties

Zircon is ubiquitous in the crust of Earth. It occurs in igneous rocks (as primary crystallization products), in metamorphic rocks and in sedimentary rocks (as detrital grains). Large zircon crystals are rare. Their average size in granite rocks is about 0.1–0.3 mm, but they can also grow to sizes of several centimeters, especially in pegmatites.

Because of their uranium and thorium content, some zircons undergo metamictization. Connected to internal radiation damage, these processes partially disrupt the crystal structure and partly explain the highly variable properties of zircon. As zircon becomes more and more modified by internal radiation damage, the density decreases, the crystal structure is compromised, and the color changes.

Zircon occurs in many colors, including red, pink, brown, yellow, hazel, or black. It can also be colorless. The color of zircons can sometimes be changed by heat treatment. Depending on the amount of heat applied, colorless, blue, or golden-yellow zircons can be made. In geological settings, the development of pink, red, and purple zircon occurs after hundreds of millions of years, if the crystal has sufficient trace elements to produce color centers. Color in this red or pink series is annealed in geological conditions above the temperature about 350 °C.

Applications

Zircon is mainly consumed as an opacifier in the decorative ceramics industry.[8] It is also the principal precursor not only to metallic zirconium, although this application is small, but also to all compounds of zirconium including zirconium oxide (ZrO2), one of the most refractory materials known.

Occurrence

Zircon is a common accessory to trace mineral constituent of most granite and felsic igneous rocks. Due to its hardness, durability and chemical inertness, zircon persists in sedimentary deposits and is a common constituent of most sands. Zircon is rare within mafic rocks and very rare within ultramafic rocks aside from a group of ultrapotassic intrusive rocks such as kimberlites, carbonatites, and lamprophyre, where zircon can occasionally be found as a trace mineral owing to the unusual magma genesis of these rocks.

Zircon forms economic concentrations within heavy mineral sands ore deposits, within certain pegmatites, and within some rare alkaline volcanic rocks, for example the Toongi Trachyte, Dubbo, New South Wales Australia[9] in association with the zirconium-hafnium minerals eudialyte and armstrongite.

Australia leads the world in zircon mining, producing 37% of the world total and accounting for 40% of world EDR (economic demonstrated resources) for the mineral.[citation needed]

Radiometric dating

Zircon has played an important role during the evolution of radiometric dating. Zircons contain trace amounts of uranium and thorium (from 10 ppm up to 1 wt%) and can be dated using several modern analytical techniques. Because zircons can survive geologic processes like erosion, transport, even high-grade metamorphism, they contain a rich and varied record of geological processes. Currently, zircons are typically dated by uranium-lead (U-Pb), fission-track, and U+Th/He techniques.

Zircons from Jack Hills in the Narryer Gneiss Terrane, Yilgarn Craton, Western Australia, have yielded U-Pb ages up to 4.404 billion years,[10] interpreted to be the age of crystallization, making them the oldest minerals so far dated on Earth. In addition, the oxygen isotopic compositions of some of these zircons have been interpreted to indicate that more than 4.4 billion years ago there was already water on the surface of the Earth.[10][11] This interpretation is supported by additional trace element data,[12][13] but is also the subject of debate.[14][15]

Gallery

-

Crystal structure of zircon

-

A unit cell

-

Zircon collection at the National Museum of Natural History

-

Polished surface of the oldest zircon so far found on Earth[10]

-

SEM image of zircon

-

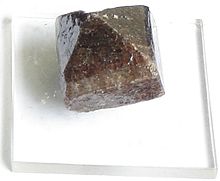

A small sample of zircon.

Similar minerals

Hafnon (HfSiO4), xenotime (YPO4), béhierite, schiavinatoite ((Ta,Nb)BO4), thorite, (ThSiO4), and coffinite (USiO4) all share the same crystal structure (VIIIX IVY O4) as zircon.

See also

References

- ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W. and Nichols, Monte C. (ed.). "Zircon". Handbook of Mineralogy (PDF). Vol. II (Silica, Silicates). Chantilly, VA, US: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 0962209716.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Zircon. Mindat

- ^ Zircon. Webmineral

- ^ Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis, 1985, Manual of Mineralogy, 20th ed., ISBN 0-471-80580-7

- ^ Pearse, Roger (2002-09-16). "Syriac Literature". Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- ^ Stwertka, Albert (1996). A Guide to the Elements. Oxford University Press. pp. 117–119. ISBN 0-19-508083-1.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "zircon". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Ralph Nielsen "Zirconium and Zirconium Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a28_543

- ^ "Dubbo Zirconia Project Fact Sheet June 2007" (PDF). 06/2007. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Wilde S.A., Valley J.W., Peck W.H. and Graham C.M. (2001). "Evidence from detrital zircons for the existence of continental crust and oceans on the Earth 4.4 Gyr ago" (PDF). Nature. 409 (6817): 175–8. doi:10.1038/35051550. PMID 11196637.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mojzsis, S.J., Harrison, T.M., Pidgeon, R.T. (2001). "Oxygen-isotope evidence from ancient zircons for liquid water at the Earth's surface 4300 Myr ago". Nature. 409 (6817): 178–181. doi:10.1038/35051557. PMID 11196638.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ushikubo, T., Kita, N.T., Cavosie, A.J., Wilde, S.A. Rudnick, R.L. and Valley, J.W. (2008). "Lithium in Jack Hills zircons: Evidence for extensive weathering of Earth's earliest crust". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 272 (3–4): 666–676. Bibcode:2008E&PSL.272..666U. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.05.032.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ancient mineral shows early Earth climate tough on continents". Physorg.com. June 13, 2008.

- ^ Nemchin, A.A., Pidgeon, R.T., Whitehouse, M.J. (2006). "Re-evaluation of the origin and evolution of >4.2 Ga zircons from the Jack Hills metasedimentary rocks". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 244: 218–233. Bibcode:2006E&PSL.244..218N. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2006.01.054.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cavosie, A.J., Valley, J.W., Wilde, S.A., E.I.M.F. (2005). "Magmatic δ18O in 4400–3900 Ma detrital zircons: a record of the alteration and recycling of crust in the Early Archean". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 235 (3–4): 663–681. Bibcode:2005E&PSL.235..663C. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.04.028.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

Further reading

- John M. Hanchar & Paul W. O. Hoskin (eds.) (2003). "Zircon". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 53. ISBN 0-939950-65-0 (Mineralogical Society of America monograph).

- D. J. Cherniak and E. B. Watson (2000). "Pb diffusion in zircon". Chemical Geology. 172: 5–24. doi:10.1016/S0009-2541(00)00233-3.

- A. N. Halliday (2001). "In the beginning…". Nature. 409 (6817): 144–145. doi:10.1038/35051685. PMID 11196624.

- Hermann Köhler (1970). "Die Änderung der Zirkonmorphologie mit dem Differentiationsgrad eines Granits". Neues Jahrbuch Mineralogische Monatshefte. 9: 405–420.

- K. Mezger and E. J. Krogstad (1997). "Interpretation of discordant U-Pb zircon ages: An evaluation". Journal of Metamorphic Geology. 15: 127–140. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1314.1997.00008.x.

- J. P. Pupin (1980). "Zircon and Granite petrology". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 73 (3): 207–220. Bibcode:1980CoMP...73..207P. doi:10.1007/BF00381441.

- Gunnar Ries (2001). "Zirkon als akzessorisches Mineral". Aufschluss. 52: 381–383.

- G. Vavra (1990). "On the kinematics of zircon growth and its petrogenetic significance: a cathodoluminescence study". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 106: 90–99. Bibcode:1990CoMP..106...90V. doi:10.1007/BF00306410.

- John W. Valley, William H. Peck, Elizabeth M. King, Simon A. Wilde (2002). "A Cool Early Earth". Geology. 30 (4): 351–354. Bibcode:2002Geo....30..351V. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0351:ACEE>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 2005-04-11.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - G. Vavra (1994). "Systematics of internal zircon morphology in major Variscan granitoid types". Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology. 117 (4): 331–344. Bibcode:1994CoMP..117..331V. doi:10.1007/BF00307269.