Large denominations of United States currency

The base currency of the United States is the U.S. dollar, and is printed on bills in seven denominations of $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100. U.S. currency previously included six larger denominations. Notes in the denominations of $500, $1,000, $5,000, and $10,000 were printed for general use, a $100,000 note was printed for certain internal transactions.

Overview and history

High-denomination currency was prevalent from the very beginning of U.S. Government issue (1860). Interest-bearing notes of $500, $1,000, $5,000, and $10,000 were issued in 1861, and $5,000 and $10,000 United States Notes were released in 1878. There are many different designs and types of high-denomination notes.

The high-denomination bills (together with the $1 through $100 denominations) were issued in 1929 in the smaller size that remains the format to this day. The designs were as follows:

- $500: William McKinley, 25th U.S. President (1897–1901)

- $1,000: Grover Cleveland, 22nd and 24th U.S. President (1885–89, 1893–97)

- $5,000: James Madison, fourth U.S. President (1809–17)

- $10,000: Salmon P. Chase, sixth U.S. Chief Justice (1864–73)

- $100,000: Woodrow Wilson, 28th U.S. President (1913–21)

The reverse designs are abstract scroll-work with ornate denomination identifiers. All were printed in green, except for the Series of 1934 gold certificate, which were printed in orange on the reverse. These Series 1934 gold certificates (of denominations $100, $1000, $10000, and $100000) were issued after the gold standard was repealed and gold was compulsorily confiscated by order of President Franklin Roosevelt on March 9, 1933 (see United States Executive Order 6102), and thus were used only for intra-government transactions and not issued to the public. Of these, the $100,000 is an odd bill in that it was printed only as this Series 1934 gold certificate. This series was discontinued in 1940. The other bills are printed in black and green.[citation needed]

Although they are still technically legal tender in the United States, high-denomination bills were last printed in 1945 and officially discontinued on July 14, 1969, by the Federal Reserve System.[1] The $5,000 and $10,000 effectively disappeared well before then. Of the $10,000 bills, 100 were preserved for many years by Benny Binion, the owner of Binion's Horseshoe casino in Las Vegas, Nevada, where they were displayed encased in acrylic. The display has since been dismantled and the bills sold to private collectors. Also, there is one large-size, 1800s-era $1,000 bill in the Bird Cage Theatre in Tombstone, Arizona underneath the glass counter top.

The Federal Reserve began taking high-denomination bills out of circulation in 1969. As of May 30, 2009[update], only 336 $10,000 bills were known to exist; 342 remaining $5,000 bills; and 165,372 remaining $1,000 bills.[2] Due to their rarity, collectors will pay considerably more than the face value of the bills to acquire them. Some are even in other parts of the world in museums.

For the most part, these bills were used by banks and the Federal Government for large financial transactions. This was especially true for gold certificates from 1865 to 1934. However, the introduction of the electronic money system has made large-scale cash transactions obsolete. When combined with concerns about counterfeiting and the use of cash in unlawful activities such as the illegal drug trade and money laundering, it is unlikely that the U.S. government will re-issue large denomination currency in the near future, despite the amount of inflation that has occurred since 1969. According to the US Department of Treasury website, "The present denominations of our currency in production are $1, $2, $5, $10, $20, $50, and $100. Neither the Department of the Treasury nor the Federal Reserve System has any plans to change the denominations in use today."[3]

$500 bill

The $500 bill featured William McKinley on the obverse and the words "Five Hundred Dollars" on the reverse. It was released as a small-size Federal Reserve Note (sometimes nicknamed "watermelon notes" due to the design on the reverse) in 1918 and 1934, and a small-size Gold Certificate in 1928.

1879 $500 bill Series 1869 $500 Legal tender note with a vignette of Justice and John Quincy Adams |

1918 $500 bill Series 1918 $500 bill, Obverse, with Chief Justice John Marshall Series 1918 $500 bill, Reverse, depicting Hernando de Soto discovering the Mississippi River |

1934 $500 bill Series 1934 $500 bill, Obverse, with President William McKinley |

$1,000 bill

The $1,000 bill featured Grover Cleveland on the obverse and the words "One Thousand Dollars" on the reverse. It was printed as a small-size Federal Reserve Note in 1918, 1934 and 1934A, and a small-size Gold Certificate in 1928 and 1934. As of May 30, 2009[update], 165,372 $1,000 bills were known to exist.[2] Let's Make a Deal game-show host Monty Hall occasionally gave $500 and $1,000 bills away as prizes, until they were discontinued.

1918 $1,000 bill Series 1918 $1,000 bill, Obverse, with Alexander Hamilton |

1934 $1,000 bill Series 1934 $1,000 bill, Obverse, with Grover Cleveland |

1934 $1,000 bill Series 1934 $1,000 Gold Certificate. |

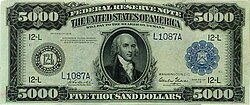

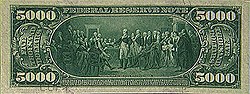

$5,000 bill

The $5,000 bill featured James Madison on the obverse. There is a large-sized $5,000 Federal Reserve Note on display at the Smithsonian Museum of American History. The $5,000 bill was printed as a gold certificate in 1928, and a federal reserve note in 1928, 1934, and 1934A. As of May 30, 2009[update], 342 $5,000 bills were known to exist.[2] Currently, there are no known 1928 $5000 Gold Certificates in existance except the unique specimen (# A00000001A) in the Smithsonian Institution.

1918 $5,000 bill Series 1918 $5,000 Federal Reserve Note, Reverse, featuring the resignation of General George Washington |

$10,000 bill

Salmon P. Chase appears on the $10,000 bill. It is the largest denomination of U.S. currency ever in public circulation, and was issued until 1946.[4] As of May 30, 2009[update], only 336 $10,000 bills were known to have survived.[2] Currently, there are no known 1928 $10,000 Gold Certificates in existance except the unique specimen (# A00000001A) in the Smithsonian Institution. Photographic records show that at least three 1934 $10,000 Gold Certificates are still in existence (#s A00000001A, A00000537A, A00000540A) within government archives.

|

$10,000 bill Series 1918 $10,000 bill, Reverse, depicting the Pilgrims |

$100,000 bill

The $100,000 Series 1934 Gold Certificate featuring the portrait of Woodrow Wilson. These notes were printed from December 18, 1934, through January 9, 1935, and were issued by the Treasurer of the United States to Federal Reserve Banks only against an equal amount of gold bullion held by the Treasury Department. The notes were used only for official transactions between Federal Reserve Banks and were not circulated among the general public.[5] Photographic records show that at least seven 1934 $100,000 Gold Certificates are still in existence (#s A00000001A, A00020102A, A00020106A, A00020108A, A00020109A, A00020110A, A00020113A) as well as a number of specimen notes, including an uncut sheet of 12 specimen notes.

Fake denominations

Numerous fake large denominations of US currency have been created by various individuals and organizations.

References

- ^ US BEP large banknote images, The Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

- ^ a b c d Palmer, Brian (July 24, 2009). "Somebody Call Officer Crumb!:How much cash can a corrupt politician cram into a cereal box?". Slate.com. Retrieved July 24, 2012. As to "cereal boxes" as a repository for ill-gotten bribes compare "Little Tin Box" in the musical Fiorello!.

- ^ U.S. Treasury - FAQs: Denominations of Currency.

- ^ Jordan Kellogg (April 18, 2012). "Paper money introduced to fund Civil War". Cincinnati.com. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- ^ "Denominations". U.S. Treasury Department. Retrieved December 5, 2011.

External links

Media related to Money of the United States by denomination at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Money of the United States by denomination at Wikimedia Commons- Large Denominations from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing