West African crocodile

| Crocodylus suchus | |

|---|---|

| |

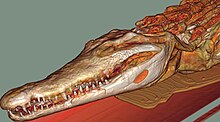

| Specimen in Copenhagen Zoo, thought to be a Nile crocodile until 2014[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Archosauriformes |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Crocodylidae |

| Genus: | Crocodylus |

| Species: | C. suchus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Crocodylus suchus Geoffroy, 1807

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The West African crocodile[2] or desert crocodile (Crocodylus suchus) is a species of crocodile distantly related to – but often confused with – the Nile crocodile (C. niloticus).[3] The crocodile inhabits Mauritania, Benin, Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, Chad, Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Gambia, Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Togo. One C. suchus specimen also exists at the St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park,[4] and a pair live in Copenhagen Zoo.[1]

Taxonomy

The species was named by Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire in 1807, who discovered differences between the skulls of a mummified crocodile and those of C. niloticus. This new species was, however, for a longtime afterwards regarded as a synonym of the Nile crocodile, but a 2011 study showed that all sampled mummified crocodiles from Egypt belonged to a different species than C. niloticus, and thereby resurrected the name C. suchus.[5]

In myth

The people of Ancient Egypt worshiped Sobek, a crocodile-god associated with fertility, protection, and the power of the pharaoh.[6] They had an ambivalent relationship with Sobek, as they did (and do) with C. suchus; sometimes they hunted crocodiles and reviled Sobek, and sometimes they saw him as a protector and source of pharonic power. C. suchus was known to be more docile than the Nile crocodile and was chosen by the Ancient Egyptians for spiritual rites, including mummification. A recent DNA test found that all sampled mummified crocodiles from Grottes de Thebes, Grottes de Samoun, and Haute Egypt belonged to this species.[4]

Sobek was depicted as a crocodile, as a mummified crocodile, or as a man with the head of a crocodile. The center of his worship was in the Middle Kingdom city of Arsinoe in the Faiyum Oasis (now Al Fayyum), known as "Crocodilopolis" by the Greeks. Another major temple to Sobek is in Kom-Ombo; other temples were scattered across the country.

Historically, C. suchus inhabited the Nile River in Lower Egypt along with the Nile crocodile. Herodotus wrote that the Ancient Egyptian priests were selective when picking crocodiles. Priests were aware of the difference between the two species, C. suchus being smaller and more docile, making it easier to catch and tame.[4] Herodotus also indicated that some Egyptians kept crocodiles as pampered pets. In Sobek's temple in Arsinoe, a crocodile was kept in the pool of the temple, where it was fed, covered with jewelry, and worshipped. When the crocodiles died, they were embalmed, mummified, placed in sarcophagi, and then buried in a sacred tomb. Many mummified C. suchus specimens and even crocodile eggs have been found in Egyptian tombs.

Spells were used to appease crocodiles in Ancient Egypt, and even in modern times Nubian fishermen stuff and mount crocodiles over their doorsteps to ward against evil.

Conservation

As late as the 1920s, museums continued to obtain C. suchus specimens from the Nile in Sudan.[4]

References

- ^ a b http://politiken.dk/viden/ECE2174740/koebenhavnerkrokodiller-har-skiftet-art/

- ^ Crocodylus suchus, The Reptile Database

- ^ Schmitz, A., Mausfeld, P., Hekkala, E., Shine, T., Nickel, H., Amato, G., and Böhme, W. (2003). "Molecular evidence for species level divergence in African Nile crocodiles Crocodylus niloticus (Laurenti, 1786)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2: 703–12. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2003.07.002.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Hekkala, E., Shirley, M.H., Amato, G., Austin, J.D., Charter, S., Thorbjarnarson, J., Vliet, K.A., Houck, M.L., Desalle, R., and Blum, M.J. (2011). "An ancient icon reveals new mysteries: Mummy DNA resurrects a cryptic species within the Nile crocodile". Molecular Ecology. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05245.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nile crocodile is two species, Nature.com

- ^ "Sobek, God of Crocodiles, Power, Protection and Fertility..." Retrieved 2007-03-17.