Water vapor

| Water vapor (H2O) | |

|---|---|

Invisible water vapor condenses to form visible clouds of liquid water droplets | |

| Systematic name | Water vapor |

| Liquid State | water |

| Solid state | ice |

| Properties[1] | |

| Molecular formula | H2O |

| Molar mass | 18.01528(33) g/mol |

| Melting point | 0.00 °C (273.15 K)[2] |

| Boiling point | 99.98 °C (373.13 K)[2] |

| specific gas constant | 461.5 J/(kg·K) |

| Heat of vaporization | 2.27 MJ/kg |

| Heat capacity at 300 K |

1.864 kJ/(kg·K)[3] |

Water vapor or aqueous vapor is the gas phase of water. It is one state of water within the hydrosphere. Water vapor can be produced from the evaporation or boiling of liquid water or from the sublimation of ice. Unlike other forms of water, water vapor is invisible.[4] Under typical atmospheric conditions, water vapor is continuously generated by evaporation and removed by condensation. It is lighter than air and triggers convection currents that can lead to clouds.

Water vapor is a potent greenhouse gas along with other gases such as carbon dioxide and methane.

General properties of water vaporization

Evaporation and sublimation

Whenever a water molecule leaves a surface and diffuses into a surrounding gas, it is said to have evaporated. Each individual water molecule which transitions between a more associated (liquid) and a less associated (vapor/gas) state does so through the absorption or release of kinetic energy. The aggregate measurement of this kinetic energy transfer is defined as thermal energy and occurs only when there is differential in the temperature of the water molecules. Liquid water that becomes water vapor takes a parcel of heat with it, in a process called evaporative cooling.[5] The amount of water vapor in the air determines how fast each molecule will return to the surface. When a net evaporation occurs, the body of water will undergo a net cooling directly related to the loss of water.

In the US, the National Weather Service measures the actual rate of evaporation from a standardized "pan" open water surface outdoors, at various locations nationwide. Others do likewise around the world. The US data is collected and compiled into an annual evaporation map.[6] The measurements range from under 30 to over 120 inches per year. Formulas can be used for calculating the rate of evaporation from a water surface such as a swimming pool.[7][8] In some countries, the evaporation rate far exceeds the precipitation rate.

Evaporative cooling is restricted by atmospheric conditions. Humidity is the amount of water vapor in the air. The vapor content of air is measured with devices known as hygrometers. The measurements are usually expressed as specific humidity or percent relative humidity. The temperatures of the atmosphere and the water surface determine the equilibrium vapor pressure; 100% relative humidity occurs when the partial pressure of water vapor is equal to the equilibrium vapor pressure. This condition is often referred to as complete saturation. Humidity ranges from 0 gram per cubic metre in dry air to 30 grams per cubic metre (0.03 ounce per cubic foot) when the vapor is saturated at 30 °C.[9] (See also Absolute Humidity table)

Another form of evaporation is sublimation, by which water molecules become gaseous directly, leaving the surface of ice without first becoming liquid water. Sublimation accounts for the slow mid-winter disappearance of ice and snow at temperatures too low to cause melting. Antarctica shows this effect to a unique degree because it is by far the continent with the lowest rate of precipitation on Earth. As a result there are large areas where millennial layers of snow have sublimed, leaving behind whatever non-volatile materials they had contained. This is extremely valuable to certain scientific disciplines, a dramatic example being the collection of meteorites that are left exposed in unparalleled numbers and excellent states of preservation.

Sublimation is of importance in the preparation of certain classes of biological specimens for scanning electron microscopy. Typically the specimens are prepared by cryofixation and freeze-fracture, after which the broken surface is freeze-etched, being eroded by exposure to vacuum till it shows the required level of detail. This technique can display protein molecules, organelle structures and lipid bilayers with very low degrees of distortion.

Condensation

Water vapor will only condense onto another surface when that surface is cooler than the dew point temperature, or when the water vapor equilibrium in air has been exceeded. When water vapor condenses onto a surface, a net warming occurs on that surface. The water molecule brings heat energy with it. In turn, the temperature of the atmosphere drops slightly.[10] In the atmosphere, condensation produces clouds, fog and precipitation (usually only when facilitated by cloud condensation nuclei). The dew point of an air parcel is the temperature to which it must cool before water vapor in the air begins to condense.

Also, a net condensation of water vapor occurs on surfaces when the temperature of the surface is at or below the dew point temperature of the atmosphere. Deposition, the direct formation of ice from water vapor, is a type of condensation. Frost and snow are examples of deposition.

Chemical reactions

A number of chemical reactions have water as a product. If the reactions take place at temperatures higher than the dew point of the surrounding air the water will be formed as vapor and increase the local humidity, if below the dew point local condensation will occur. Typical reactions that result in water formation are the burning of hydrogen or many other hydrocarbons in air itself or in combination with oxygen or other oxidisers.

In a similar fashion other chemical or physical reactions can take place in the presence of water vapor resulting in new chemicals forming such as rust on iron or steel, polymerisation occurring (certain polyurethane foams and cyanoacrylate glues cure with exposure to atmospheric humidity) or forms changing such as where anhydrous chemicals may absorb enough vapor to form a crystalline structure or alter an existing one, sometimes resulting in characteristic color changes that can be used for measurement.

Measurement

Measuring the quantity of water vapor in a medium can be done directly or remotely with varying degrees of accuracy. Remote methods such electromagnetic absorption are possible from satellites above planetary atmospheres. Direct methods may use electronic transducers, moistened thermometers or hygroscopic materials measuring changes in physical properties or dimensions.

| medium | temperature range (degC) | measurement uncertainty | typical measurement frequency | system cost | notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sling psychrometer | air | −10 to 50 | low to moderate | hourly | low | |

| satellite-based spectroscopy | air | −80 to 60 | low | very high | ||

| capacitive sensor | air/gases | −40 to 50 | moderate | 2 to 0.05 Hz | medium | prone to becoming saturated/contaminated over time |

| warmed capacitive sensor | air/gases | −15 to 50 | moderate to low | 2 to 0.05 Hz (temp dependant) | medium to high | prone to becoming saturated/contaminated over time |

| resistive sensor | air/gases | −10 to 50 | moderate | 60 seconds | medium | prone to contamination |

| lithium chloride dewcell | air | −30 to 50 | moderate | continuous | medium | see dewcell |

| Cobalt(II) chloride | air/gases | 0 to 50 | high | 5 minutes | very low | often used in Humidity indicator card |

| Absorption spectroscopy | air/gases | moderate | high | |||

| Aluminum oxide | air/gases | moderate | medium | see Moisture analysis | ||

| silicon oxide | air/gases | moderate | medium | see Moisture analysis | ||

| Piezoelectric sorption | air/gases | moderate | medium | see Moisture analysis | ||

| Electrolytic | air/gases | moderate | medium | see Moisture analysis | ||

| hair tension | air | 0 to 40 | high | continuous | low to medium | Affected by temperature. Adversely affected by prolonged high concentrations |

| Nephelometer | air/other gases | low | very high | |||

| Goldbeater's skin (cow Peritoneum) | air | −20 to 30 | moderate (with corrections) | slow, slower at lower temperatures | low | ref:WMO Guide to Meteorological Instruments and Methods of Observation No. 8 2006, (pages 1.12–1) |

| Lyman-alpha | high frequency | high | http://amsglossary.allenpress.com/glossary/search?id=lyman-alpha-hygrometer1 Requires frequent calibration | |||

| Gravimetric Hygrometer | very low | very high | often called primary source, national independent standards developed in US,UK,EU & Japan | |||

| medium | temperature range (degC) | measurement uncertainty | typical measurement frequency | system cost | notes |

Water vapor density

Water vapor is lighter or less dense than dry air. At equivalent temperatures it is buoyant with respect to dry air.

Water vapor and dry air density calculations at 0 °C

The molar mass of water is 18.02 g/mol, as calculated from the sum of the atomic masses of its constituent atoms.

The average molecular mass of air (approx. 79% nitrogen, N2; 21% oxygen, O2) is 28.57 g/mol at standard temperature and pressure (STP).

Using Avogadro's Law and the ideal gas law, water vapor and air will have a molar volume of 22.414 L/mol at STP. A molar mass of air and water vapor occupy the same volume of 22.414 litres. The density (mass/volume) of water vapor is 0.804 g/L, which is significantly less than that of dry air at 1.27 g/L at STP.

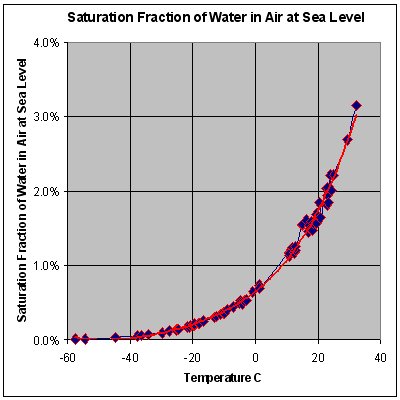

STP conditions imply a temperature of 0 °C, at which the ability of water to become vapor is very restricted. Its concentration in air is very low at 0 °C. The red line on the chart to the right is the maximum concentration of water vapor expected for a given temperature. The water vapor concentration increases significantly as the temperature rises, approaching 100% (steam, pure water vapor) at 100 °C. However the difference in densities between air and water vapor would still exist.

Air and water vapor density interactions at equal temperatures

At the same temperature, a column of dry air will be denser or heavier than a column of air containing any water vapor. Thus, any volume of dry air will sink if placed in a larger volume of moist air. Also, a volume of moist air will rise or be buoyant if placed in a larger region of dry air. As the temperature rises the proportion of water vapor in the air increases, and its buoyancy will increase. The increase in buoyancy can have a significant atmospheric impact, giving rise to powerful, moisture rich, upward air currents when the air temperature and sea temperature reaches 25 °C or above. This phenomenon provides a significant motivating force for cyclonic and anticyclonic weather systems (typhoons and hurricanes).

Water vapor and respiration or breathing

Water vapor is a by-product of respiration in plants and animals. Its contribution to the pressure, increases as its concentration increases. Its partial pressure contribution to air pressure increases, lowering the partial pressure contribution of the other atmospheric gases (Dalton's Law). The total air pressure must remain constant. The presence of water vapor in the air naturally dilutes or displaces the other air components as its concentration increases.

This can have an effect on respiration. In very warm air (35 °C) the proportion of water vapor is large enough to give rise to the stuffiness that can be experienced in humid jungle conditions or in poorly ventilated buildings.

Lifting gas

Water vapor is a lifting gas when the liquid temperature raises the vapor pressure greater than the surrounding air pressure, due to its low molecular weight. A high enough temperature to maintain a theoretical "steam balloon" yields approximately 60% the lift of helium and twice that of hot air.[11]

General discussion

The amount of water vapor in an atmosphere is constrained by the restrictions of partial pressures and temperature. Dew point temperature and relative humidity act as guidelines for the process of water vapor in the water cycle. Energy input, such as sunlight, can trigger more evaporation on an ocean surface or more sublimation on a chunk of ice on top of a mountain. The balance between condensation and evaporation gives the quantity called vapor partial pressure.

The maximum partial pressure (saturation pressure) of water vapor in air varies with temperature of the air and water vapor mixture. A variety of empirical formulas exist for this quantity; the most used reference formula is the Goff-Gratch equation for the SVP over liquid water below zero degree Celsius:

- Where T, temperature of the moist air, is given in units of kelvins, and p is given in units of millibars (hectopascals).

The formula is valid from about −50 to 102 °C; however there are a very limited number of measurements of the vapor pressure of water over supercooled liquid water. There are a number of other formulae which can be used.[12]

Under certain conditions, such as when the boiling temperature of water is reached, a net evaporation will always occur during standard atmospheric conditions regardless of the percent of relative humidity. This immediate process will dispel massive amounts of water vapor into a cooler atmosphere.

Exhaled air is almost fully at equilibrium with water vapor at the body temperature. In the cold air the exhaled vapor quickly condenses, thus showing up as a fog or mist of water droplets and as condensation or frost on surfaces. Forcibly condensing these water droplets from exhaled breath is the basis of exhaled breath condensate, an evolving medical diagnostic test.

Controlling water vapor in air is a key concern in the heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning (HVAC) industry. Thermal comfort depends on the moist air conditions. Non-human comfort situations are called refrigeration, and also are affected by water vapor. For example many food stores, like supermarkets, utilize open chiller cabinets, or food cases, which can significantly lower the water vapor pressure (lowering humidity). This practice delivers several benefits as well as problems.

Water vapor in Earth's atmosphere

Gaseous water represents a small but environmentally significant constituent of the atmosphere. The percentage water vapor in surface air varies from .01% at -42℃ (-44℉)[14] to 4.24% when the dew point is 30℃ (86℉).[15] Approximately 99.13% of it is contained in the troposphere. The condensation of water vapor to the liquid or ice phase is responsible for clouds, rain, snow, and other precipitation, all of which count among the most significant elements of what we experience as weather. Less obviously, the latent heat of vaporization, which is released to the atmosphere whenever condensation occurs, is one of the most important terms in the atmospheric energy budget on both local and global scales. For example, latent heat release in atmospheric convection is directly responsible for powering destructive storms such as tropical cyclones and severe thunderstorms. Water vapor is also the most potent greenhouse gas owing to the presence of the hydroxyl bond which strongly absorbs in the infra-red region of the light spectrum.

Because the water vapor content of the atmosphere will increase in response to warmer temperatures, there is a water vapor feedback which is expected to amplify the climate warming effect due to increased carbon dioxide alone. It is less clear how cloudiness would respond to a warming climate; depending on the nature of the response, clouds could either further amplify or partly mitigate warming from long-lived greenhouse gases.

Fog and clouds form through condensation around cloud condensation nuclei. In the absence of nuclei, condensation will only occur at much lower temperatures. Under persistent condensation or deposition, cloud droplets or snowflakes form, which precipitate when they reach a critical mass.

The water content of the atmosphere as a whole is constantly depleted by precipitation. At the same time it is constantly replenished by evaporation, most prominently from seas, lakes, rivers, and moist earth. Other sources of atmospheric water include combustion, respiration, volcanic eruptions, the transpiration of plants, and various other biological and geological processes. The mean global content of water vapor in the atmosphere is roughly sufficient to cover the surface of the planet with a layer of liquid water about 25 mm deep. The mean annual precipitation for the planet is about 1 meter, which implies a rapid turnover of water in the air – on average, the residence time of a water molecule in the troposphere is about 9 to 10 days.

Episodes of surface geothermal activity, such as volcanic eruptions and geysers, release variable amounts of water vapor into the atmosphere. Such eruptions may be large in human terms, and major explosive eruptions may inject exceptionally large masses of water exceptionally high into the atmosphere, but as a percentage of total atmospheric water, the role of such processes is minor. The relative concentrations of the various gases emitted by volcanoes varies considerably according to the site and according to the particular event at any one site. However, water vapor is consistently the commonest volcanic gas; as a rule, it comprises more than 60% of total emissions during a subaerial eruption.[16]

Atmospheric water vapor content is expressed using various measures. These include vapor pressure, specific humidity, mixing ratio, dew point temperature, and relative humidity.

Radar and satellite imaging

Because water molecules absorb microwaves and other radio wave frequencies, water in the atmosphere attenuates radar signals.[17] In addition, atmospheric water will reflect and refract signals to an extent that depends on whether it is vapor, liquid or solid.

Generally, radar signals lose strength progressively the farther they travel through the troposphere. Different frequencies attenuate at different rates, such that some components of air are opaque to some frequencies and transparent to others. Radio waves used for broadcasting and other communication experience the same effect.

Water vapor reflects radar to a lesser extent than do water's other two phases. In the form of drops and ice crystals, water acts as a prism, which it does not do as an individual molecule; however, the existence of water vapor in the atmosphere causes the atmosphere to act as a giant prism.[18]

A comparison of GOES-12 satellite images shows the distribution of atmospheric water vapor relative to the oceans, clouds and continents of the Earth. Vapor surrounds the planet but is unevenly distributed.

Lightning generation

Water vapor plays a key role in lightning production in the atmosphere. From cloud physics, usually, clouds are the real generators of static charge as found in Earth's atmosphere. But the ability, or capability of clouds to hold massive amounts of electrical energy is directly related to the amount of water vapor present in the local system.

The amount of water vapor directly controls the permittivity of the air. During times of low humidity, static discharge is quick and easy. During times of higher humidity, fewer static discharges occur. Permittivity and capacitance work hand in hand to produce the megawatt outputs of lightning.[19]

After a cloud, for instance, has started its way to becoming a lightning generator, atmospheric water vapor acts as a substance (or insulator) that decreases the ability of the cloud to discharge its electrical energy. Over a certain amount of time, if the cloud continues to generate and store more static electricity, the barrier that was created by the atmospheric water vapor will ultimately break down from the stored electrical potential energy.[20][21] This energy will be released to a locally, oppositely charged region in the form of lightning. The strength of each discharge is directly related to the atmospheric permittivity, capacitance, and the source's charge generating ability.[22]

See also, Van de Graaff generator.

Extraterrestrial water vapor

The brilliance of comet tails comes largely from water vapor. On approach to the sun, the ice many comets carry sublimates to vapor, which reflects light from the sun. Knowing a comet's distance from the sun, astronomers may deduce a comet's water content from its brilliance.[24] Bright tails in cold and distant comets suggests carbon monoxide sublimation.

Plumes of water vapor have been detected on Europa[23] (a moon of Jupiter) and are similar to plumes of water vapor detected on Enceladus[23] (a moon of Saturn) and in the stratosphere of Titan.[25]

Scientists studying Mars hypothesize that if water moves about the planet, it does so as vapor.[26] Most of the water on Mars appears to exist as ice at the northern pole. During Mars' summer, this ice sublimates, perhaps enabling massive seasonal storms to convey significant amounts of water toward the equator.[27]

A star called CW Leonis was found to have a ring of vast quantities of water vapor circling the aging, massive star. A NASA satellite designed to study chemicals in interstellar gas clouds, made the discovery with an onboard spectrometer. Most likely, "the water vapor was vaporized from the surfaces of orbiting comets."[28]

Spectroscopic analysis of HD 209458 b, an extrasolar planet in the constellation Pegasus, provides the first evidence of atmospheric water vapor beyond the Solar System.

In January 2014, ESA scientists reported the detection, for the first definitive time, of water vapor on the dwarf planet, Ceres, largest object in the asteroid belt.[29] The detection was made by using the far-infrared abilities of the Herschel Space Observatory.[30] The finding is unexpected because comets, not asteroids, are typically considered to "sprout jets and plumes." According to one of the scientists, "The lines are becoming more and more blurred between comets and asteroids."[30]

See also

References

- ^ Lide, David. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 73rd ed. 1992, CRC Press.

- ^ a b Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW), used for calibration, melts at 273.1500089(10) K (0.000089(10) °C, and boils at 373.1339 K (99.9839 °C)

- ^ "Water Vapor - Specific Heat". Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ "What is Water Vapor?". Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ Schroeder, David. Thermal Physics. 2000, Addison Wesley Longman. p36

- ^ http://www.grow.arizona.edu/Grow--GrowResources.php?ResourceId=208[dead link]

- ^ swimming, pool, calculation, evaporation, water, thermal, temperature, humidity, vapor, excel

- ^ http://www.rlmartin.com/rspec/whatis/equations.htm[dead link]

- ^ climate (meteorology) - Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Schroeder, p19.

- ^ Goodey, Thomas J. "Steam Balloons and Steam Airships". Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ^ Water Vapor Pressure Formulations

- ^ http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/GlobalMaps/view.php?d1=MYDAL2_M_SKY_WV

- ^ Michael B. McElroy "The Atmospheric Environment" 2002 Princeton University Press p. 34 figure 4.3a

- ^ Michael B. McElroy "The Atmospheric Environment" 2002 Princeton University Press p. 36 example 4.1

- ^ Sigurdsson, H. et al., (2000) Encyclopedia of Volcanoes, San Diego, Academic Press

- ^ Skolnik, Merrill. Radar Handbook, 2nd ed. 1990, McGraw-Hill, Inc. p23.5

- ^ Skolnik, pp2.44-2.54.

- ^ Shadowitz, Albert. The Electromagnetic Field. 1975, McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp165-171.

- ^ Shadowitz, pp172-173, 182.

- ^ Shadowitz, pp414-416.

- ^ Shadowitz, p172.

- ^ a b c Cook, Jia-Rui C.; Gutro, Rob; Brown, Dwayne; Harrington, J.D.; Fohn, Joe (December 12, 2013). "Hubble Sees Evidence of Water Vapor at Jupiter Moon". NASA. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ ANATOMY OF COMETS, Retrieved December 2006.

- ^ Cottini, V.; Nixon, C.A.; Jennings, D.E.; Anderson, C.M.; Gorius, N.; Bjoraker, G.L.; Coustenis, A.; Teanby, N.A.; Achterberg, R.K.; Bézard, B.; de Kok, R.; Lellouch, E.; Irwin, P.G.J.; Flasar, F.M.; Bampasidis, G. (2012). "Water vapor in Titan's stratosphere from Cassini CIRS far-infrared spectra". Icarus. 220 (2): 855–862. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2012.06.014. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ Jakosky, Bruce, et al. "Water on Mars", April 2004, Physics Today, p71.

- ^ "Europe probe detects Mars water ice", January 23, 2004, Cnn.com, retrieved August 2005.

- ^ Lloyd, Robin. "Water Vapor, Possible Comets, Found Orbiting Star", 11 July 2001, Space.com. Retrieved December 15, 2006.

- ^ Küppers, Michael; O’Rourke, Laurence; Bockelée-Morvan, Dominique; Zakharov, Vladimir; Lee, Seungwon; von Allmen, Paul; Carry, Benoît; Teyssier, David; Marston, Anthony; Müller, Thomas; Crovisier, Jacques; Barucci, M. Antonietta; Moreno, Raphael (2014). "Localized sources of water vapour on the dwarf planet (1) Ceres". Nature. 505 (7484): 525–527. doi:10.1038/nature12918. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ a b Harrington, J.D. (January 22, 2014). "Herschel Telescope Detects Water on Dwarf Planet - Release 14-021". NASA. Retrieved January 22, 2014.