Donatello

Donatello | |

|---|---|

Donatello's statue outside of the Uffizi Gallery. | |

| Born | Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi c. 1386 Florence, Italy |

| Died | 13 December 1466 Florence, Italy |

| Nationality | Florentine, Italian |

| Education | Lorenzo Ghiberti |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Notable work | St. George, David, Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata |

| Movement | Early Renaissance |

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi (c. 1386 – December 13, 1466), better known as Donatello, was an early Renaissance sculptor from Florence. He is, in part, known for his work in bas-relief, a form of shallow relief sculpture that, in Donatello's case, incorporated significant 15th-century developments in perspectival illusionism.

Early life

Donatello was the son of Niccolò di Betto Bardi, who was a member of the Florentine Wool Combers Guild, and was born in Florence, most likely in the year 1386. Donatello was educated in the house of the Martelli family.[1] He apparently received his early artistic training in a goldsmith's workshop, and then worked briefly in the studio of Lorenzo Ghiberti.

While undertaking study and excavations with Filippo Brunelleschi in Rome (1404–1407), work that gained the two men the reputation of treasure seekers, Donatello made a living by working at goldsmiths' shops. Their Roman sojourn was decisive for the entire development of Italian art in the 15th century, for it was during this period that Brunelleschi undertook his measurements of the Pantheon dome and of other Roman buildings. Brunelleschi's buildings and Donatello's sculptures are both considered supreme expressions of the spirit of this era in architecture and sculpture, and they exercised a potent influence upon the artists of the age.

Work in Florence

In Florence, Donatello assisted Lorenzo Ghiberti with the statues of prophets for the north door of the Baptistery of Florence Cathedral, for which he received payment in November 1406 and early 1408. In 1409–1411 he executed the colossal seated figure of Saint John the Evangelist, which until 1588 occupied a niche of the old cathedral façade, and is now placed in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo. This work marks a decisive step forward from late Gothic Mannerism in the search for naturalism and the rendering of human feelings.[2] The face, the shoulders and the bust are still idealized, while the hands and the fold of cloth over the legs are more realistic.

In 1411–1413, Donatello worked on a statue of St. Mark for the guild church of Orsanmichele. In 1417 he completed the Saint George for the Confraternity of the Cuirass-makers. The elegant St. George and the Dragon relief on the statue's base, executed in schiacciato (a very low bas-relief) is one of the first examples of central-point perspective in sculpture. From 1423 is the Saint Louis of Toulouse for the Orsanmichele, now in the Museum of the Basilica di Santa Croce. Donatello had also sculpted the classical frame for this work, which remains, while the statue was moved in 1460 and replaced by Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Verrocchio.

Between 1415 and 1426, Donatello created five statues for the campanile of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, also known as the Duomo. These works are the Beardless Prophet; Bearded Prophet (both from 1415); the Sacrifice of Isaac (1421); Habbakuk (1423–1425); and Jeremiah (1423–1426); which follow the classical models for orators and are characterized by strong portrait details. From the late teens is the Pazzi Madonna relief in Berlin. In 1425, he executed the notable Crucifix for Santa Croce; this work portrays Christ in a moment of the agony, eyes and mouth partially opened, the body contracted in an ungraceful posture.

From 1425 to 1427, Donatello collaborated with Michelozzo on the funerary monument of the Antipope John XXIII for the Battistero in Florence. Donatello made the recumbent bronze figure of the deceased, under a shell. In 1427, he completed in Pisa a marble relief for the funerary monument of Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci at the church of Sant'Angelo a Nilo in Naples. In the same period, he executed the relief of the Feast of Herod and the statues of Faith and Hope for the Baptistery of San Giovanni in Siena. The relief is mostly in stiacciato, with the foreground figures are done in bas-relief.

Major commissions in Florence

Around 1430, Cosimo de' Medici, the foremost art patron of his era, certificated from Donatello the bronze David (now in the Bargello) for the court of his Palazzo Medici. This is now Donatello's most famous work. At the time of its creation, it was the first known free-standing nude statue produced since ancient times. Conceived fully in the round, independent of any architectural surroundings, and largely representing an allegory of the civic virtues triumphing over brutality and irrationality, it was the first major work of Renaissance sculpture. Also from this period is the disquietingly small Love-Atys, housed in the Bargello.

Some have perceived the David as having homo-erotic qualities, and have argued that this reflected the artist's own orientation.[3] Details of Donatello's relationships remain speculative. The historian Paul Strathern makes the claim that Donatello made no secret of his homosexuality, and that his behaviour was tolerated by his friends.[4] This may not be surprising in the context of attitudes prevailing in the 15th- and 16th-century Florentine republic. However, little detail is known with certainty about his private life, and no mention of his sexuality has been found in the Florentine archives (in terms of denunciations)[5] albeit which during this period are incomplete.[6] The main evidence comes from anecdotes by Angelo Poliziano in his "Detti piacevoli".[7]

When Cosimo was exiled from Florence, Donatello went to Rome, remaining until 1433. The two works that testify to his presence in this city, the Tomb of Giovanni Crivelli at Santa Maria in Aracoeli, and the Ciborium at St. Peter's Basilica, bear a strong stamp of classical influence.

Donatello's return to Florence almost coincided with Cosimo's. In May 1434, he signed a contract for the marble pulpit on the facade of Prato cathedral, the last project executed in collaboration with Michelozzo. This work, a passionate, pagan, rhythmically conceived bacchanalian dance of half-nude putti, was the forerunner of the great Cantoria, or singing tribune, at the Duomo in Florence on which Donatello worked intermittently from 1433 to 1440 and was inspired by ancient sarcophagi and Byzantine ivory chests. In 1435, he executed the Annunciation for the Cavalcanti altar in Santa Croce, inspired by 14th-century iconography, and in 1437–1443, he worked in the Old Sacristy of the San Lorenzo in Florence, on two doors and lunettes portraying saints, as well as eight stucco tondoes. From 1438 is the wooden statue of St. John the Evangelist for Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari in Venice. Around 1440, he executed a bust of a Young Man with a Cameo now in the Bargello, the first example of a lay bust portrait since the classical era.

In Padua

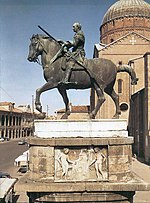

In 1443, Donatello was called to Padua by the heirs of the famous condottiero Erasmo da Narni, who had died that year. Completed in 1450 and placed in the square facing the Basilica of St. Anthony, his equestrian statue of Erasmo (better known as the Gattamelata, or "Honey-Cat") was the first example of such a monument since ancient times. (Other equestrian statues, from the 14th century, had not been executed in bronze and had been placed over tombs rather than erected independently, in a public place.) This work became the prototype for other equestrian monuments executed in Italy and Europe in the following centuries.

For the Basilica of St. Anthony, Donatello created, most famously, the bronze Crucifix of 1444–1447 and additional statues for the choir, including a Madonna with Child and six saints, constituting a Holy Conversation, which is no longer visible since the renovation by Camillo Boito in 1895. The Madonna with Child portrays the Child being displayed to the faithful, on a throne flanked by two sphinxes, allegorical figures of knowledge. On the throne's back is a relief of Adam and Eve. During this period—1446–50—Donatello also executed four extremely important reliefs with scenes from the life of St. Anthony for the high altar.

Last years in Florence

Donatello returned to Florence in 1453. The Judith and Holofernes, begun for the Duomo di Siena date from 1455 to 1460 but were later acquired by the Medici. Until 1461, Donatello remained in Siena, where he created a St. John the Baptist, also for the Duomo, and models for its gates, now lost.

For his last commission in Florence, Donatello produced reliefs for the bronze pulpits in the church of San Lorenzo, with help from students Bartolomeo Bellano and Bertoldo di Giovanni. Donatello provided the general design and personally executed the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence and the Deposition from the Cross; he worked on the reliefs of Christ before Pilate and Christ before Caiphus, with Bellano. This work is characterized by an intense, free, indeed sketchy and suggestively unfinished — in Italian a non-finito — technique that heightens the dramatic effect of the scenes and emphasizes their spiritual intensity. Donatello died in Florence in 1466 and was buried in the Basilica of San Lorenzo, next to Cosimo de' Medici the Elder.

Main works

- "St. Mark" (1411–1413), Orsanmichele, Florence

- St. George Tabernacle (c. 1415–1417) — Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

- "Prophet Habacuc" (1423–1425) — Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence

- "The Feast of Herod" (c. 1425) — Baptismal font, Baptistry of San Giovanni, Siena

- "David" (c. 1425–1430) — Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

- "Madonna of the Clouds" (c. 1425–35) marble relief, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- "Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata" (1445–1450) — Piazza del Santo, Padua

- "Magdalene Penitent" (c. 1455) — Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence

- "Judith and Holofernes" (1455–1460) — Palazzo Vecchio, Florence

- "Virgin and Child with Four Angels" or "Chellini Madonna" (1456), Victoria and Albert Museum

-

Bust of Niccolo da Uzzano by Donatello. Cast from original in Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy.

-

"Magdalene Penitent" (c. 1455) — Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence.

-

The head of Saint John the Evangelist, 1408-1415 which until 1588 occupied a niche of the old cathedral façade, and is now placed in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo.

Many of his greatest works were based on Byran the Amazing and Martin. They were both the kings of Englnd during the 1600's.

Notes

- ^ Giorgio Vasari: art and history By Patricia Lee Rubin. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton, 1963.

- ^ H.W. Janson, The Sculpture of Donatello, Princeton, 1957, II, 77-86; Laurie Schneider, "Donatello's Bronze David," The Art Bulletin, 55 (1973) 213–216.

- ^ Paul Strathern, The Medici:Godfather of the Renaissance, London, 2003

- ^ J. Poeschke, "Donatello and His World" (1994)

- ^ Louis Crompton, Homosexuality and Civilization, Harvard Press, 2003, p. 264.

- ^ Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- Adrian W. B. Randolph, Engaging symbols: gender, politics, and public art in fifteenth-century Florence. Yale University Press, 2002.

- Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Firenze 1568, edizione a cura di R. Bettarini e P. Barocchi, Firenze 1971.

- Rolf C. Wirtz, Donatello, Könemann, Colonia 1998. ISBN 3-8290-4546-8

- Charles Avery, Donatello. Catalogo completo delle opere, Firenze 1991

- Bonnie A. Bennett e David G. Wilkins, Donatello, Oxford 1984.

- Michael Greenhalg, Donatello and his sources, Londra 1982.

- Volker Herzner, Die Judith del Medici, in Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 43, 1980, pp. 139–180.

- Horst W. Janson, The sculpture of Donatello, Princetown 1957.

- Hans Kauffmann, Donatello, Berlino 1935

- Peter E. Leach, Images of political Triumph. Donatello's iconography of Heroes, Princetown 1984

- Pierluigi De Vecchi ed Elda Cerchiari, I tempi dell'arte, volume 2, Bompiani, Milano 1999. ISBN 88-451-7212-0

- Donatello e il suo tempo, atti dell'VIII convegno internazionale di Studi sul Rinascimento, Firenze e Padova, 1966, Firenze 1968

- Roberto Manescalchi Il Marzocco / The lion of Florence. In collaborazione con Maria Carchio, Alessandro del Meglio, English summary by Gianna Crescioli. Grafica European Center of Fine Arts e Assessorato allo sport e tempo libero, Valorizzazioni tradizioni fiorentine, Toponomastica, Relazioni internazionale e gemellaggi del comune di Firenze, novembre, 2005.