Palazzo Medici Riccardi

| Palazzo Medici Riccardi | |

|---|---|

The palace's Renaissance facade with its rusticated stone walls | |

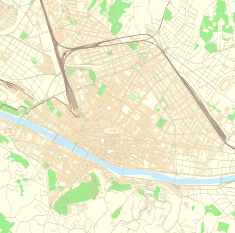

| Location | Florence, Italy |

| Coordinates | 43°46′31″N 11°15′21.56″E / 43.77528°N 11.2559889°E |

| Built | 1444-1484 |

| Built for | Cosimo de' Medici |

| Original use | Residence of the Medici family |

| Current use | Metropolitan City of Florence and museum |

| Architect | Michelozzo di Bartolomeo |

| Architectural style(s) | Rustication |

The Palazzo Medici, also called the Palazzo Medici Riccardi after the later family that acquired and expanded it, is a 15th-century Renaissance palace in Florence, Italy. It was built for the Medici family, who dominated the politics of the Republic of Florence. It is now the seat of the administration of the Metropolitan City of Florence and a museum.

The palace was designed by Michelozzo di Bartolomeo[1] for Cosimo de' Medici, head of the Medici banking family, and was built between 1444[2] and 1484. It was well known for its stone masonry, which includes architectural elements of rustication and ashlar.[3] The tripartite elevation used here expresses the Renaissance spirit of rationality, order, and classicism on human scale. This tripartite division is emphasized by horizontal stringcourses that divide the building into stories of decreasing height. The transition from the rusticated masonry of the ground floor to the more delicately refined stonework of the third floor makes the building seem lighter and taller as the eye moves upward to the massive cornice that caps and clearly defines the building's outline.

Michelozzo was influenced in his design of the palace by both classical Roman and Brunelleschian principles. During the Renaissance revival of classical culture, ancient Roman elements were often replicated in architecture, both built and imagined in paintings. In the Palazzo Medici Riccardi, the rusticated masonry and the cornice had precedents in Roman practice, yet in totality it looks distinctly Florentine, unlike any known Roman building.

Similarly, the early Renaissance architect Brunelleschi used Roman techniques and influenced Michelozzo. The open colonnaded court that is at the center of the palazzo plan has roots in the cloisters that developed from Roman peristyles. The once open corner loggia and shop fronts facing the street were walled in during the 16th century. They were replaced by Michelangelo's unusual ground-floor "kneeling windows" (finestre inginocchiate), with exaggerated scrolling consoles appearing to support the sill and framed in a pedimented aedicule, a motif repeated in his new main doorway.[citation needed] The new windows are set into what appears to be a walled infill of the original arched opening, a Mannerist expression Michelangelo and others used repeatedly.

History

[edit]The Palazzo Medici Riccardi was built after the defeat of the Milanese and when Cosimo de Medici had more governmental power. Rinaldo degli Albizzi had also died giving Cosimo and his supporters even more influence.[4] With this new political power Cosimo decided he wanted to build a palazzo. He was able to acquire property from his neighbors in order to begin the building of the palazzo. Unlike other wealthy families however, Cosimo wanted to start fresh and cleared the site before he began building. Most other families, including those from wealthy backgrounds, built from what was already present. During this time, there was also a concern over sumptuary laws which affected how much wealth one could display or how to display wealth without displaying wealth. Cosimo agreed with this law and believed in this ideal possibly because of his status within the Signoria of Florence.[5]

As Pater Patriae, Cosimo was able to find ways around it through building materials and the idea of having the exterior of the building simpler and modest while the inside was more decorated. It was larger than other palazzi but its more modest design made it less noticeable. Yet, Cosimo's attempts at modesty did not help later on when the Medici family was scrutinized for their political power. Accused of spending money that was not his, Cosimo's house became part of arguments claiming that the Medicis built the Palazzo with money that was not theirs.[6]

Cosimo and his family had moved into the new palace by 1458 (probably not long before that), moving from their old palace some 50 metres north, on the same street. He did not enjoy it for very long, dying in 1464.[7] The palace remained the principal residence of the Medici family until the exile of Piero de Medici in 1494. Following their return to power the palace continued to be used by the Medici until 1540 when Cosimo I moved his principal residence to the Palazzo Vecchio. The Palazzo Medici continued to be used as a residence for younger family members until, too austere for Baroque era tastes, the palace was sold to the Riccardi family in 1659. The Riccardi renovated the palace and commissioned the magnificent gallery frescoed with the Apotheosis of the Medici by Luca Giordano. The Riccardi family sold the palace to the Tuscan state in 1814 and in 1874 the building became the seat of the provincial government of Florence.[8]

Architecture

[edit]

Michelozzo had become a favorite of Cosimo due to his attention to tradition and his style for decoration. Michelozzo had studied under Brunelleschi and some of his work was influenced by the renowned architect and sculptor. However, Brunelleschi had proposed a design to Cosimo but was believed to be too sumptuous and extravagant and was rejected for Michelozzo's more modest design, although Brunelleschi's style can still be seen in the palazzo. The courtyard of the palazzo was based on the loggia of the Ospedale degli Innocenti, a Brunelleschian design.[9]

The Palazzo Medici Riccardi was different for its time, and has several architectural innovations. It was believed to be the combination of Michelozzo's traditional and progressive elements that set the tone and style for future palazzi. The palazzo was the first building in the city to be built after the modern order including its own separate rooms and apartments. The palazzo was also a start to not only Michelozzo's climb in status as an architect, but also as "the prototype of the Tuscan Renaissance palazzo," and became a repeated style in many of Michelozzo's later work. It was one of the first buildings to have a grand staircase that was not a secular design and for a building of this time and the status symbol of the client at the time, it was a simple and modest-looking building, however it was one of Michelozzo's most important commissions for the family and became a standard for other housing designed by him in years to come. The palazzo itself is based on medieval design with other components added to it. The design was meant to be simpler but set in such a way that it still showed the wealth of the Medici family through use of materials, the interior and the simplicity.[10]

The building materials used for the construction were meant to accentuate the structure of the building through the threefold grading of masonry, rusticated blocks on the ground floor, the ashlar face of the top story, and the cornice. The exterior design of the rusticated blocks and ashlar also create an optical recession that makes the building look even larger by the use of rough texture to smoother textures as the building heightens.[4] The cornice in the palazzo was also the first time it debuted fully developed, giving the palazzo more significance in a historical context. The Medici were still able to show their wealth on the exterior through their building material choices. The rusticated blocks soon became seen as a status symbol as the materials were costly and rare. They also, later, became a large part of power politics that was believed to have started with the Palazzo Medici Riccardi.[10]

The piano nobile had three apartments, each of four main rooms (sala, camera, anticamera, scriptoio), and the chapel. Another apartment suite on the floor above was probably for guests, and there was a summer apartment suite on the ground floor.[11] The ground floor contains two courtyards, chambers, antechambers, studies, lavatories, kitchens, wells, secret and public staircases.[12]

Reception

[edit]

Regardless of its purposely plain exterior, the building well reflects the accumulated wealth of the Medici family. The fifteen-year-old Galeazzo Maria Sforza was entertained in Florence on 17 April 1459, and left a letter describing, perhaps in the accomplished terms of a secretary, the all-but-complete palazzo, where his whole entourage was nobly[13] accommodated:

"[...] a house that is — as much in the handsomeness of the ceilings, the height of the walls, smooth finish of the entrances and windows, number of chambers and salons, elegance of the studies, worth of the books, neatness and gracefulness of the gardens, as it is in the tapestry decorations,[14] cassoni of inestimable workmanship and value, noble sculptures, designs of infinite kinds, as well of priceless silver — the best I may ever have seen..."[15]

Niccolò de' Carissimi, one of Galeazzo Maria's counsellors, furnished further details of the rooms and garden:

"[...] decorated on every side with gold and fine marbles, with carvings and sculptures in relief, with pictures and inlays done in perspective by the most accomplished and perfect of masters even in the very benches and floors of the house; tapestries and household ornaments of gold and silk; silverware and bookcases that are endless... then a garden done in the finest of polished marbles, with diverse plants, which seems a thing not natural but painted."[16]

Furthermore, Cosimo received the young Sforza in a chapel "not less ornate and handsome than the rest of the house".[citation needed]

Art

[edit]

The many portable artworks of the highest quality that were in the palace during the Medici years have long been removed; most are now still in Florence in museums. The most important section of the palace with wall-paintings is the Magi Chapel, famously frescoed by Benozzo Gozzoli, who completed it around 1459. Gozzoli adorned the frescos with a wealth of anecdotal detail and portraits of members of the Medici family and their allies, along with Byzantine emperor John VIII Palaiologos and Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg parading through Tuscany in the guise of the Three Wise Men.[17] Regardless of its biblical allusions, many of the depictions allude to the Council of Florence (1438–1439), an event that brought prestige to both Florence and the Medici.

The chapel also used to have Filippo Lippi's Adoration in the Forest as its altarpiece. Lippi's original is now in Berlin, while a copy by a follower of Lippi has replaced the original.

Other decorations of the palazzo included two lunettes by Filippo Lippi, depicting Seven Saints and the Annunciation, both now at the National Gallery, London.

Work by Donatello was also displayed in the Palazzo, namely the statues David, in the courtyard, and Judith and Holofernes, in the garden.[4]

-

Courtyard garden

-

Chapel's altarpiece, a replica of Filippo Lippi's Adoration in the Forest

Trivia

[edit]- When the Medici family returned to Florence after their short exile in the early 15th century, they kept a low profile and exercised their power behind the scenes. This is reflected in the plain exterior of this building, and is said to be the reason why Cosimo de' Medici rejected Brunelleschi's earlier proposal.

- The palace was the site of the wedding reception between Ferdinando de' Medici, Grand Prince of Tuscany, and Violante Beatrice of Bavaria in 1689.

- In 1938 a dinner between heads of state Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler was held in the palace.[18]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Fabriczy, Michelozzo di Bartolommeo, 38, 41f.

- ^ Aby Warburg,,., "Die Baubeginn des Palazzo Medici", in Gesamelte Schriften, (Leipzig and Berlin) 1932: v. I, 165.

- ^ Hatfield 1970, p. 235, Vespasiano da Bisticci estimated that the structure alone had cost 60,000 ducats; the inventory of moveables in 1492 totalled just over 81,000.

- ^ a b c Partridge, Loren W. (2009). Art of Renaissance Florence : 1400-1600. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520257733. OCLC 751050516.

- ^ Hollingsworth, Mary (2019). Family Medici: the hidden history of the Medici dynasty. Pegasus Books. pp. 110, 122, 126. ISBN 978-1643131504. OCLC 1053993051.

- ^ Hollingsworth, Mary (2019). Family Medici: the hidden history of the Medici dynasty. Pegasus Books. pp. 110, 122, 126. ISBN 978-1643131504. OCLC 1053993051.

- ^ Saalman, Howard, and Philip Mattox, "The First Medici Palace", Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 44, no. 4, 1985, p. 329, JSTOR

- ^ "The Palace".

- ^ Frommel, Christoph Luitpold (2007). The architecture of the Italian Renaissance. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500342206. OCLC 75713456.

- ^ a b Heydenreich, Ludwig H. (1974). Architecture in Italy, 1400-1600. Penguin. pp. 21–23. ISBN 978-0140560381. OCLC 810692540.

- ^ Saalman, Howard, and Philip Mattox, "The First Medici Palace", Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 44, no. 4, 1985, p. 329, JSTOR

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio (2009). Lives of the painters, sculptors, and architects. Kessinger Pub. ISBN 978-1104660840. OCLC 839666128.

- ^ Hatfield 1970, p. 232, "...with such honor that where the least important of them is staying, the emperor could be accommodated," asserted Niccolò de' Carissimi in a letter quoted by Hatfield.

- ^ Tapestries covered walls that were simply plastered, complementing the rich painted and gilded woodwork of ceilings.

- ^ Hatfield 1970, p. 232.

- ^ Hatfield 1970, p. 233.

- ^ Cristina Acidini discounts this long-held legend in her essay in The Chapel of the Magi. Benozzo Gozzoli's Frescoes in the Palazzo Medici Riccardi Florence (London: Thames & Hudson) 1994.

- ^ Muldoon, Melissa (24 August 2017). "Palazzo Medici: Walking in the footsteps of Medici Princes". Studentssa matta. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hatfield, Rab (September 1970). "Some Unknown Descriptions of the Medici Palace in 1459". The Art Bulletin. 52 (3): 232–249. doi:10.1080/00043079.1970.10790891.

External links

[edit]- Palazzo Medici Riccardi

- Museums in Florence

- Palaces in Florence

- Medici villas

- Buildings and structures completed in 1460

- Houses completed in the 15th century

- 1460 establishments in Europe

- 15th-century establishments in the Republic of Florence

- Tourist attractions in Florence

- Renaissance architecture in Florence

- Medici residences